By Jocelyn Hitchcock, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

It’s no secret that women are vastly underrepresented in the historical record. Biographical information, even about some of the most prominent women like Cleopatra, is often gleamed from tangential accounts focused on male counterparts. Of course this doesn’t mean that women did not making massive contributions to arts, sciences, and way of life, it just means we have to dig a little more for a complete or even semi-complete image. While there are so many impressive and transformative women from antiquity to choose from, both for good reasons and bad, below are five women whose contributions sent shock waves through time.

1. Cleopatra

No list of influential women from antiquity would be complete without the mention of Cleopatra. Love her or hate her, her impact on the Egyptian and Roman worlds, as well as our own, cannot be ignored.

Cleopatra was born in 69 BCE and famously died on August 30, 30 BCE, a year after her and Marc Antony’s defeat at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE; Cleopatra’s failed attempts to maintain power. Cleopatra was the last pharaoh of Egypt and also the last of the Ptolemeic rulers. Growing up, she studied medicine, philosophy, rhetoric, and oration and spoke many languages including Greek, Latin, and Egyptian.

Cleopatra ascended to rule in March of 51 BCE alongside her brother and husband, Ptolemy XIII. After about two years, Ptolemy XIII was in a more powerful position than Cleopatra, with Pompey of Rome naming him the sole ruler of Egypt. The two rose armies against one another. Pompey was assassinated by Ptolemy’s camp, and Julius Caesar arrived in Egypt hoping to get the armies and Egyptian rulers to come to some sort of reconciliation. What resulted was the death of Ptolemy XIII in battle and the political and romantic alliance between Cleopatra and Caesar. Despite the fact that he was already married, Caesar and Cleopatra had a child together. While Caesar never officially claimed paternity, the name Ptolemy Caesarion left little room for question.

Caesar brought

Cleopatra to Rome in the midst of rising political tensions. This, in conjunction with the way Caesar had been constantly and blatantly pushing the boundaries with regards to what was acceptable for a politician to do, led to his assassination in 44 BCE. Cleopatra returned to Egypt afterwards.

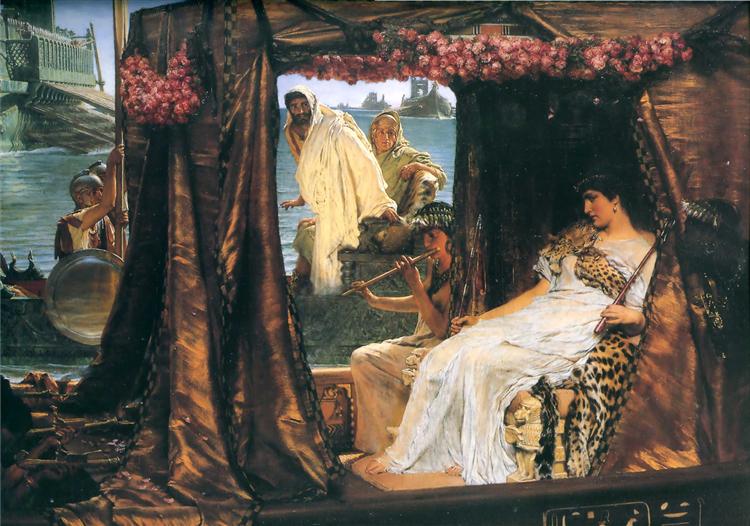

Anthony and Cleopatra on the Nile by Lawrence Alma Tadema

Cleopatra’s legacy is one that lives on in plays like Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, Hollywood’s Cleopatra, and has captured the interest of the public for thousands of years. Her contributions to women’s rule, her ability to participate actively on the world political and military stage, and her sheer involvement in Roman and Egyptian politics on such an intricate level cements her as one of the most notorious women of the ancient world.

2. Livia (58 BCE – 29 CE)

Living in the same era as Cleopatra, Livia Drusilla was wife to Emperor Augustus and heavily impacted the process and succession of the Roman Empire during Augustus’ rule and immediately after his death.

Livia was married to Tiberius Claudius Nero before Augustus, to whom she bore two sons, Tiberius and Nero Claudius Drusus. In 38 BCE, (then) Octavian arranged for her divorce and then marriage to himself, which resulted in no children. Throughout Augustus’ reign as emperor, Livia worked behind the scenes, learning the ins and outs of the new government, and becoming increasingly aware that she wanted her sons to ascend to rulership upon Augustus’ death, even though they were not blood-heirs.

Interestingly, unfortunately, or coincidently- however you choose to see it- all of the legitimate heirs and close relatives of Augustus had either died or been exiled before his death, leaving just Livia’s sons as potential successors. Tiberius ascended to the position of emperor, and Livia continued to work on politics and state affairs until her death in 29. Additionally, Livia was a big proponent of the cult of Augustus after his death, and was instrumental in his deification. Tiberius resented his mother’s ambition, apparently, and drastically limited and reduced her influence and power, even in her will. Her grandson, Claudius, however, deified her in 42.

Livia’s legacy lives on as the first lady to the Roman Empire. She is often portrayed as cold and calculating, with some even going so far (in antiquity and in modern times) to suggest that she was the one who orchestrated the demise of all potential heirs except her own sons. However, this is nearly impossible to discern the truth. What we are unequivocally left with is an image of an intelligent, persuasive, and powerful woman who was able to stand alongside, but not in the shadow of, her male partner.

3. Agrippina the Younger

A few generations after Livia, her great- granddaughter Agrippina the Younger was carrying out dealings similar to that of Livia herself. She originally married in 28 AD a man named Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and together they had a son, the eventual emperor Nero. Ahenobarbus died in 40, and in 41 she was remarried to her uncle, the emperor Claudius. Emperor Claudius already had a son, Britannicus, but Agrippina convinced Claudius to officially adopt her son Nero, making it possible for him to be a legitimate heir. Claudius died, from what some early historians suspected was poisoning at the hand of Agrippina herself, and Nero did assume power at 16/17 years old.

Agrippina acted as the regent to Nero, but not for long. Nero grew annoyed with her domineering actions and exiled her. Agrippina and Nero grew into a bitter dissolution of their relationship, with Agrippina going so far as to say that Nero was not the rightful heir to the throne, but Brittanicus, Claudius’ legitimate son, was. Nero plotted his mother’s assassination, with one attempt sinking a boat that Agrippina evaded by swimming back to shore. Eventually, she was assassinated in her home.

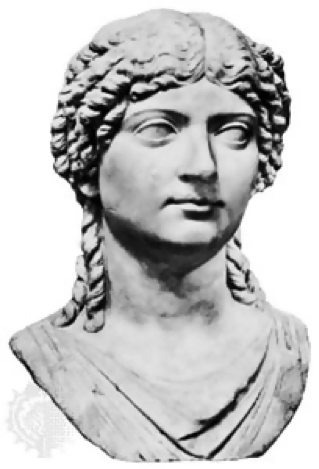

Agrippina and Nero

Agrippina was perhaps the ultimate helicopter parent of the time. She so desperately wanted her own power, and saw her son as the perfect vehicle to attain it. She was strong willed, confident, and talented in the art of politics and persuasion. While she did prop up one of Rome’s most fatal emperors in Nero, her impact on the line of succession and the actions of Nero make her a notorious figure in the ancient past.

4. Hatshepshut

Traveling much further back in time than the Roman Empire, Hatshepsut of Egypt became pharaoh with full powers in 1473 BCE. She was the daughter of King Thutmose I and married her half brother, Thutmose II, when she was 12 years old. She acted as regent for Thutmose III, her stepson, upon Thutmose II’s death.

After 7 years, though, Hatshepsut took on the full powers and responsibilities of a pharaoh. This was unprecedented and many thought it was due to her own ambition to grasp at power. However, this could have been a political move to defend the throne and safeguard its stability against internal and external threats.

In some imagery, she was portrayed as male with a beard and musculature that would have worked as a piece of propaganda to try and legitimize her position.

Hatshepsut took on extensive building projects in Thebes, engaged Egypt in lucrative trading ventures, and increased the wealth of the kingdom. She likely died in her mid-40s and was buried in the Valley of the Kings. Her stepson, Thutmose III continued his rule but eventually had all the evidence of Hatshepsut’s rule scrubbed from temples and monuments.

5. Hypatia of Alexandria

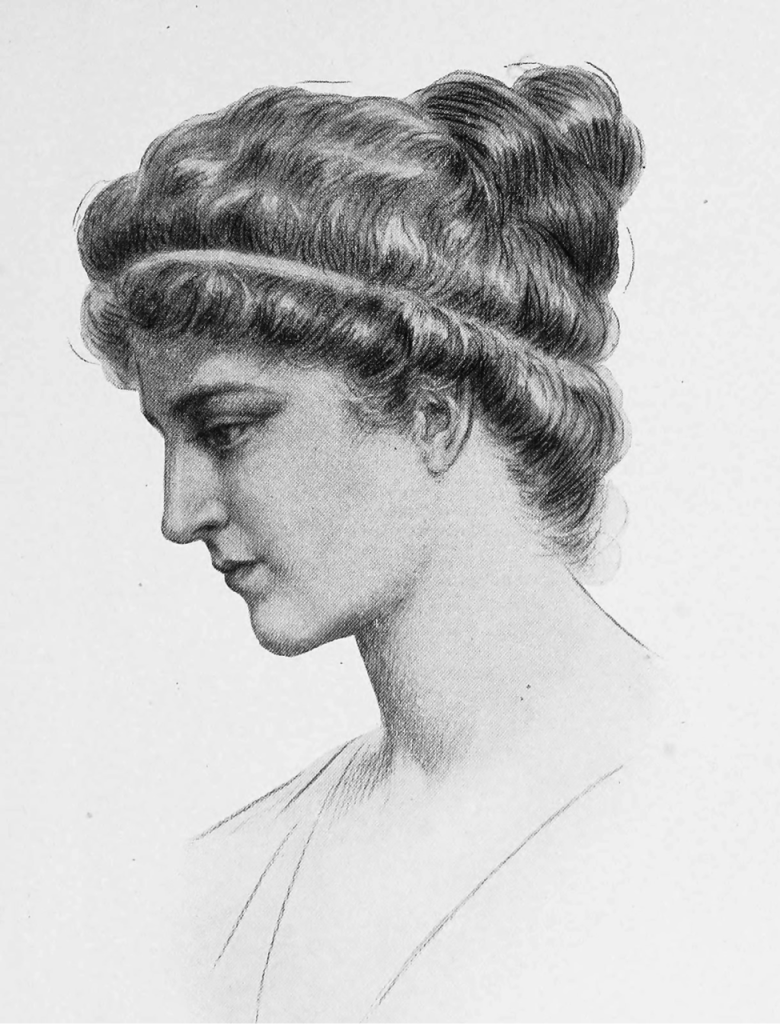

Hypatia was born around 355 CE and died March of 415 in Alexandria. Her father, Theon of Alexandria, was also a prominent mathematician and upon his death Hypatia aimed to keep up with his work. She produced major contributions to geometry, number theory, and astronomy.

Illustration of Hypatia of Alexandria

During her life,

the city of Alexandria itself was in utter turmoil. Conflict between Christians, Jews, and Pagans plagued the city, and Hypatia’s perceived paganism and intellect ultimately proved to be the cause of her death. Peter the Lector, the leader of a Christian mob, attacked her carriage and dragged Hypatia into a church where they stripped her and beat her to death with tiles, upon which she was incinerated. Her legacy was eventually reclaimed by feminists, philosophers,and scientists alike. She has been held up as one of the last truly great ‘thinkers’ of the ancient world.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.