Written by Tom G. Hamilton, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The Roman historian Tacitus tells us that the Celts made no distinction of sex when appointing their commanders and in western Iberia. According to the Greek historian Strabo, women fought alongside men. For the Celts, a woman could not only wage war—she was also a warrior herself.

But first: what were the Celts doing in western Iberia? After all, the first countries that come to mind when one thinks of Celtic culture are not Spain and Portugal, which principally comprise the Iberian peninsula (along with a small area of southern France and Gibraltar). But the Celts did indeed live there—and had for a long time. In fact, DNA studies link Celtic roots to the Iberian peninsula. In ancient times, Celtic culture was associated with all of Atlantic Europe—an area that encompasses the British Isles, Portugal, Belgium, parts of Spain, France and northern Germany—creating a major cultural division between Atlantic and Central Europe.

This divide can be seen in many areas. For example, unlike other European cultures, in the Celtic world, domestic roles went out the window in the event of war. In conflict situations Celtic women dropped what they were doing and took up arms.

It was no surprise then that Celtic Queen Boudica, who is known to history for leading a revolt against Rome, had been initiated into the elite warrior class. She rose quickly in the army’s ranks until she had earned the respect of invading Roman legionaries and generals alike. Boudica came very close to changing Rome’s ambitions about Britain forever.

The tribal confederation of Queen Boudica were known as the Vettones. They were a warrior people, and indeed the word Vetton comes from the Celtic roots UEK–TI meaning “warrior.” War was their default mode of existence, and it included women.

The Vetton female warriors were hardly an anomaly in Celtic culture—on the contrary, many Celtic women were skilled fighters. Indeed, an unknown Roman soldier allegedly once said: “A Celtic woman is often the equal of any Roman man in hand-to-hand combat. She is as beautiful as she is strong. Her body is comely but fierce. The physiques of our Roman women pale in comparison.”

Further descriptions of these Celtic women in hand-to-hand combat are even more detailed and should not be omitted from our attention. Greek historian Appian of Alexandria, describing Sextus Junius Brutus’ campaigns against the Celtic tribes in Lusitania, writes:

“Here he found the women fighting and perishing in company with the men with such bravery that they uttered no cry even in the midst of slaughter.” (Appian, The Spanish Wars, 15: 71,72)

Regarding Gaulish women, the Roman soldier and historian Ammianus Marcellinus writes:

“A whole band of foreigners will be unable to cope with one [Gaul] in a fight, if he calls in his wife, stronger than he by far and with flashing eyes; least of all when she swells her neck and gnashes her teeth, and poising her huge white arms, begins to rain blows mingled with kicks, like shots discharged by the twisted cords of a catapult.” — Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman Antiquities, Book XV – 12

Celtic lore and legend celebrated women as valiant and warlike. Take Aoife and Scathach, two rival female warriors from folklore, for example.

Scathach had taught Cú Chulainn, the Irish mythological demigod and great warrior in Irish and Scottish legends. He insisted on taking Scathach’s place in a one-to-one combat challenge called by Aoife. In the combat she reduced his sword to a stump but he, knowing beforehand that her most precious things were her two horses and chariot, distracted her attention by saying her horses and chariot were falling off a distant cliff. Aoife turned back and in that moment Cú managed to overpower her. According to the story, they ended up as lovers and she bore Cú a son.

Whilst motherhood and nurturing were considered sacred feminine qualities in the Celtic tradition, courage and ability to fight in close combat were considered equally important. Celtic spirituality and warfare were not mutually exclusive; on the contrary, they were intertwined. A similar fluidity can be seen in gender roles. Being a man in Celtic society and culture had no macho overtone. Calling on your wife as equal—or even superior—to assist you wasn’t considered a weakness. What’s more, a woman could train a man in the art of warfare.

Perhaps Aoife and Scathach really existed and the legend was based upon truth, or maybe it was just apocryphal. Regardless, such stories portray the Celtic woman as both warriors and mothers—and such is our Boudica.

Back in Iberia, the Romans described the women as having a small shield upon which they beat a rhythm. This, almost assuredly, was the adufe, or square frame drum still played by the women today in Beira Baixa. These rhythms, played exclusively by women even now, strongly resemble the sound of a horse. In this way, music also played a part in the pre-battle ceremony.

It’s likely such drums were heard when Boudica, who had assumed the role of a spiritual authority as well as military leader, was giving a speech to her fellow warriors to prepare them for the final conflict and battle against the Romans. She invoked the name of the female Andrasta, the goddess of the Iceni, whilst taking a hare from inside her cloak and releasing it as part of a shamanic prophecy of coming victory.

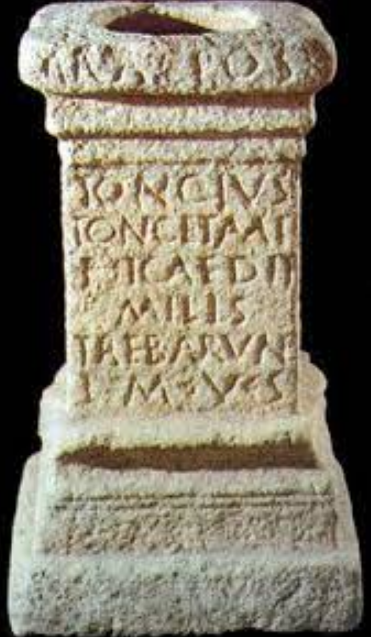

In Beira Baixa, land of the Vettones, this deity was called Trebaruna, which means house of mystery. Boudica had grown up in a hillfort, considered the sacred high places of the Celts. Warrior training took place within the hillfort culture, and Boudica would have been accustomed to a level of personal discipline that would challenge most of us to the core. This was part of her warrior elite training, although training is perhaps not the most suitable word—it was more of an initiation.

The initiate into the Celtic warrior elite became another person altogether. The would-be warriors were initiated into the world of death. They were driven to the limits of endurance, to the edges of their own personal tolerance of pain and hardship. The initiate would then, at the end, possess another version of themselves. They would come out from the realms of death into a new life as a warrior. The Ver Sacrum part of this warrior initiation prepared them for leaving home. Thus, it was perfectly natural for Boudica to leave her Iberian homeland.

The future queen had been taught how to survive in extreme conditions. She learned to be frugal, to live off nature’s most simple provisions of roots and berries, to deal with extremities of the natural world, of heat and cold, and to handle pain itself. Her formation had given her all this, along with weapons training and, being a Vetton—the Vettones were famed for their horsemanship—she had a natural command over horses.

Her skills did not go unnoticed. Boudica had been chosen to represent Rome in the region along with her husband Tagus. They enjoyed the perks and had become somewhat wealthy—until Boudica decided that Rome’s greediness had gone too far.

As an elite ALAE (Alae Vettonum Hispanorum, the Vetton Winged Cavalry) Boudica would have fought alongside the Roman legions, flanking them to one side on her horse. This must have been a source of intrigue and fascination to the Roman foot-soldiers, giving them an inside view into the secret world of the Celtic warrior elite. They evidently knew her habits and even observed how she dressed—or as Tacitus described it, her “invariable attire.” (Cassius Dio, Roman History, LXII:1-2)

The Romans would have been familiar with her battle cries and with her god. Her voice was described as strong, authoritative, expressing her conviction and character, and equally impressive as her physical presence. However, we should not confuse this with sexuality. There are no sexual overtones in the description of Boudica by the classical writers. Rather, the tone was one of awe of her person, her warrior’s bearing, and her courage.

The modern idea of the Celtic warrior princess has been sexualized. These depictions were created to entertain men’s fantasies—big-breasted, tall, imposing and heavily-armed vixens designed as characters within the virtual-reality war video games market.

This, however, has no historical basis. Boudica apparently filled her Roman admirers with profound respect. Perhaps she made them question their own Roman sexist moral attitudes. In truth, the two cultures were worlds apart. Here was proof that a woman could ride a horse and wield deadly weapons alongside Roman generals. These women could create legends and inflict deadly wounds on their enemies.

But it is not only modern audiences that have reinvented the Celtic warrior. Medieval writers often had an issue with what they considered to be Boudica’s acts of violence. They seem too extreme, too cruel, so some writers in the early Middle Ages tried to divide her in two. Petruccio Ubaldini in La vite del donne illustri del Regno D’Inghliterra, e del regno di Scotia (1591) split Boudica into two queens, Voadicia the “good” queen, and Bunduica, the “bad” one. He talks about her as being cruel and degrading, and lacking in compassion in her treatment of the prisoners.

In a sense, there were two Boudicas—but not as the medieval writers proposed. There was the Boudica that served the Romans—and the Boudica that turned on the Romans. In her lifetime, Rome’s ever-expanding empire came, saw, and relentlessly conquered the known world. It crushed whatever people and culture that dared stand in the way, often with great cruelty.

Boudica was singularly brave in standing up to Roman power at its height. Not only did she confront Rome, she fought back with intelligence, cunning and precision, as Celtic warrior women of her day were trained to do. She gave Rome a good beating. Stung, Rome retreated only to return with no mercy, but Boudica lived on in the hearts and lore of the Celts, where she is revered to this day.

References:

The Cultural and Ideological Significance Of Representations of Boudica During the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I, by Samantha Frénée-Hutchins, p. 22.

3 comments

A most interesting article but it would have helped a lot to have a little more factual context such as the dates when she was fighting alongside the Romans, when and where she forced them to pull back and then when and where they returned to beat her.

Thank you for this excellent comment! This is actually going to be the introduction to a much larger book, which is why the author didn’t go into so much detail. However, we have passed on your remarks to ensure this is addressed fully in future chapters.

Boudica is always fascinating. Like Arminius in Germania during the Augustan age, she turned against the Romans, although Arminius’s actions are understood as a grand betrayal. Interesting information about the geographic & cultural history of the Celts.

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.