by Zoe Grabow

It’s one of the earliest concepts in Greek philosophy.

The arche was first conceived of over 2,500 years ago. While it is hardly scientific, it is still relevant to how we perceive our existence today. It is an elemental life force from which all things emerge, and essentially early philosophy’s answer to the question of what is the true “beginning” of things. It was a major area of concern for the Pre-Socratic philosophers, who spent lot of effort deciding which element was deserving enough to be called the arche and why. The concept of the arche is deeply linked to monism, the belief that all of the universe is made of a single element. Different Pre-Socratics each came to their own conclusions about what exactly this fundamental substance could be. Let’s have a look…

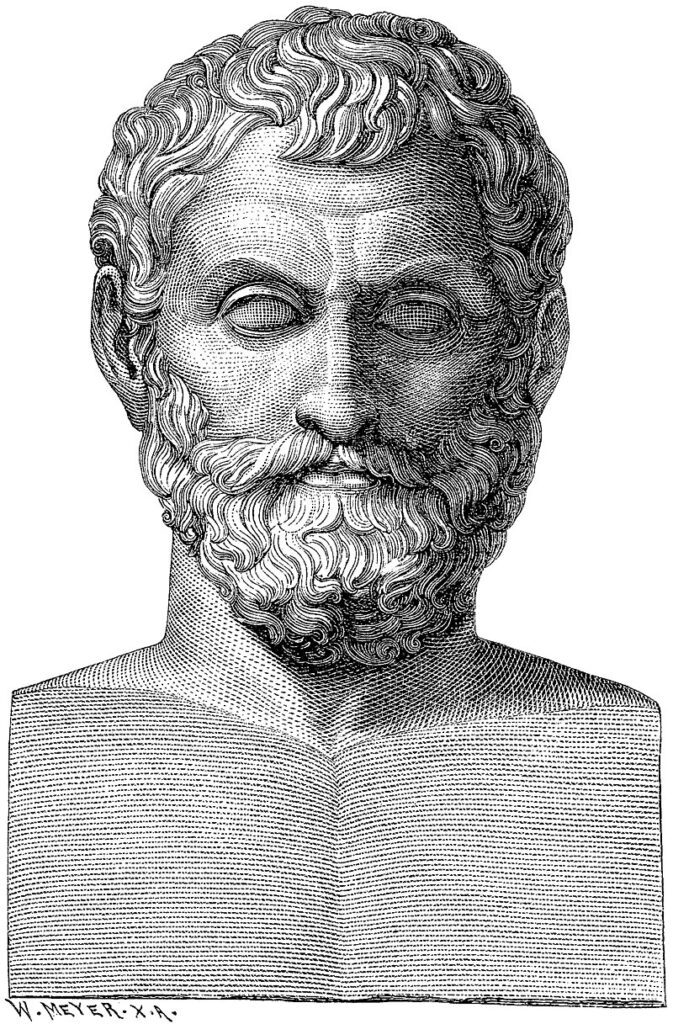

Thales of Miletus

Thales of Miletus, the earliest Greek philosopher, thought the arche to be water, since many things float in water. This was a particularly compelling point, as in ancient times land was believed to float in water as well. Though since disproven, the idea of water as arche was nevertheless intuitive; a certain degree of moisture is always present in food, the air, and ourselves. Life cannot exist without it.

Anaximenes

Anaximenes identified air as the arche. Air, he stated, could be modified to create water through condensation, fire through rarefication, and (somewhat less credibly) even earth and stone through further condensation. Given that people breathe much more often than during other voluntary activities—and that people die the fastest when deprived of air—their inextricable link to the substance they breathe informs this choice of arche. Air is essential to life, making it a natural pick for philosophers trying to find the most basic life-giving principle.

That many species breathe air is indisputable, and breathing could be understood as the most basic activity of living. Breathing makes consciousness possible, makes energy, eating, drinking water, and hygienic activities possible. If we rest the world only on human shoulders, this might be the most fitting arche selection

Anaximander

Taking a different approach from Thales (his teacher) and Anaximenes (his student), Anaximander argued that the arche was the apeiron: often translated as indefinite, or as humans understand it, the great unknown. Water could not work, he claimed, because it could not produce fire, its opposite element. Extrapolating this to the other elements, he found that no element could work in creating its opposite in a world where all four were present. Therefore, for his first principle Anaximander turned to the great unknown, from which humans originate and where eventually they will return.

Anaximander’s wisdom comes in endorsing an arche that is difficult to prove or disprove, by virtue of the unknown contained in the great unknown. Humans’ lack of knowledge regarding existence before birth and after death make this quite a palatable theory. One thrills at all of the possibilities: reincarnation, naturalism (the belief that humans return to a state of nothingness when they die), or the religious concept of heaven, among countless others. Life limits people’s observations, and any experience outside the lifespan can be argued for but not proven. By identifying the arche as the indefinite, Anaximander ascribed to the world the following qualities: temporal, changeable, and vast, much like the human lifespan. Yet the indefinite seems to reach beyond humanity, as well—little can escape the unknown—and is objective enough to nominate the best, widest-reaching arche choice of the Milesians.

A Different Approach

Each of these ideas is compelling, but they all have their limitations. Perhaps the problem is not with the concept of the arche, but with a strict understanding of monism. Yet a different approach is possible. The key is understanding that priority monism argues that the world is the sum of its parts; each part is dependent on other parts and the overall whole. Fire, water, earth, air, the unknown: any combination of these is present in everyday living. Fire and water mean food, which nourishes in a way it could not if these elements were acting separately. Add water to earth and plants grow. Combine the unknown with any element in a scientific experiment, and with luck and skill new knowledge is revealed.

Each combination is stronger and has more variation than a singular use, and is at its most powerful with all parts acting simultaneously. Thales, Anaximenes, and Anaximander may be ancient philosophers, but their ideas can still be experienced today through simple appreciation of the elements and the unknown—and how all these enhance lives, especially in combination.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.