By Van Bryan, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

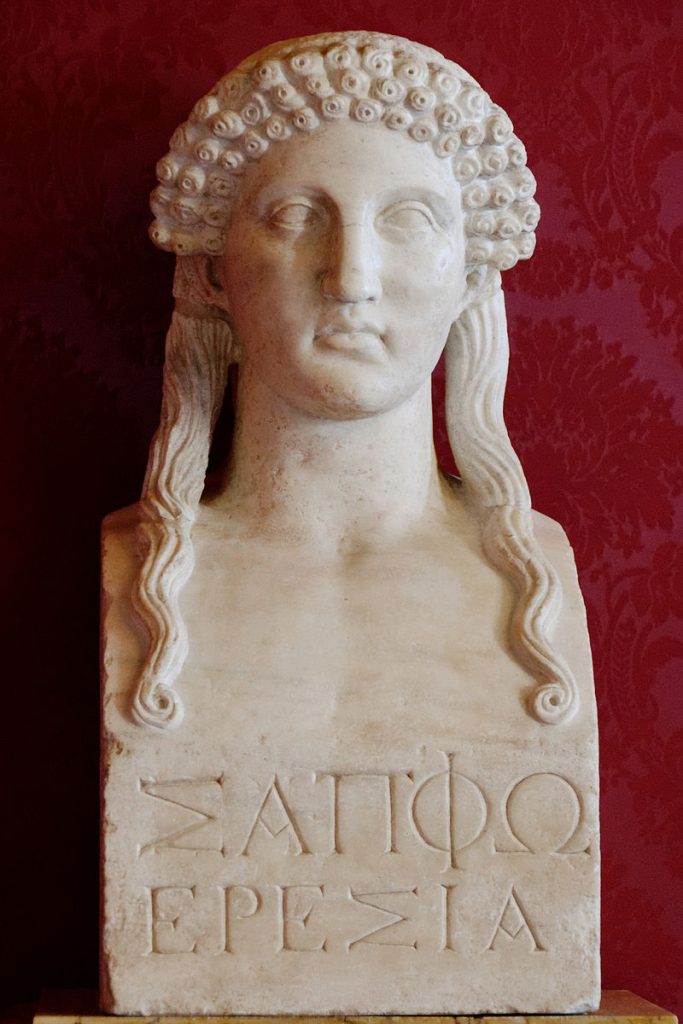

Besides being born on the island of Lesbos around 630 BCE (and this date is often disputed), surprisingly little is known about the life of this beloved poet. The only reliable source of biographical information about Sappho comes from her own poetry. Additionally, much of her writing has been lost to the ages. We do know, however, that she was considered the equal of Homer and numbered among the Nine Lyric Poets of ancient Greece. She was prolific and wrote around 10,000 lines (about 2,000 less than the Odyssey), but today only about 650 lines survive.

Still, her name has survived, and her reputation as a gifted lyrical poet with it. She wrote extensively about love and passion for all peoples, and for both men and women.

These discoveries have lead to the assumption that Sappho was a lesbian. The term “lesbian” derives from the name of her homeland Lesbos, and the term “sapphic love” is derived from the poet’s own name. We may never know for sure if Sappho loved women; the love for women described in her poetry may have been entirely fictional. But given that she is believed to have written of her life in other fragments, this seems unlikely.

However, in her own time period, she was not considered gay. Quite the opposite: in classical Athenian comedy (from the Old Comedy of the fifth century, to Menander in the late fourth and early third centuries BC), Sappho was caricatured as a promiscuous heterosexual woman. It wasn’t until the Hellenistic period (about three centuries after her death), that she was described as a homosexual.

Some ancient writers assumed that there had to have been two Sapphos: one the great poet, the other a very promiscuous woman. There is an entry for each in the Suda, the large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world.

The truth is, we can only draw conclusions from various scraps of poetry that have been attributed to Sappho. And they really are ‘scraps’. All of the surviving works by Sappho are partially destroyed, save for Hymn for Aphrodite. More than half of the original lines survive in around ten more fragments and the rest of the extant fragments of Sappho contain only a single word. Her poems are actually categorized as fragment 1- fragment 213. These fragments have been attributed to several books that the poet is believed to have authored during her literary career.

Recently, there have been major discoveries of more of Sappho’s poetry. In 2004, the Tithonus Poem and a new, previously unknown fragment was discovered, and in 2014, fragments of nine poems: five already known but with new readings, including the Brothers Poem, were found in an ancient Egyptian vase.

Even though very little of her work has survived, from what remains we can determine that Sappho was extraordinarily talented. She possessed a clarity of language and simplicity of thought that creates images that are sharply defined and beautifully constructed.

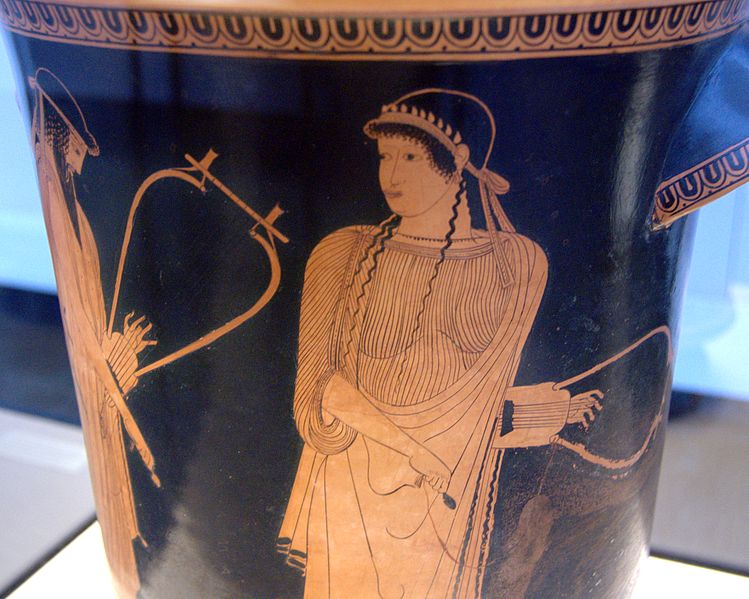

She wrote and sung in an Aeolian dialect, a type of Ancient Greek that was a pitch-accented language, a bit like Chinese is today. She used a rhythmic scheme that Sappho is said to have invented called the “Sapphic Stanza”. Each four-line stanza consists of three metrically identical lines, eleven syllables in length, followed by a shorter fourth line of five syllables.

She was admired by other poets of her time. One Greek author, writing three centuries after her death, confidently predicted that “the white columns of Sappho’s lovely song endure / and will endure, speaking out loud . . . as long as ships sail from the Nile.”

Solon, the poet, statesman and all-round wiseman, asked to be taught one of her songs “so that I may learn it and then die”

The philosopher Plato wrote of her in the Anthologia Graeca, a collection of ancient poems by esteemed writers, when he states:

“Some say the Muses are nine: how careless! Look, there’s Sappho too, from Lesbos, the tenth.”

While much of her work has been lost, we still maintain enough poetry from Sappho to appreciate her skill as a poet and her importance as an ancient writer.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.