Written by Leigh Duffy, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

While yoga has exploded in popularity in the last twenty years or so, the larger system of yoga—of which the physical practice is a mere part—has been around since before the time of Aristotle. This eight-limbed (or eight-part) system of yoga, which was developed just after Aristotle’s time, is rooted in a rich philosophical school of thought addressing metaphysical questions about the nature of the universe, the nature of humanity, and the nature of knowledge.

This ancient school of thought addresses how our knowledge about the universe and our place in it can help us live better lives. In other words, it proposes answers to questions that Aristotle himself was asking. Aristotle had different answers, but there are many similarities. Those similarities help teach us how to live noble and virtuous lives.

The yoga practice developed by Patañjali in The Yoga Sūtras sometime between the 2nd Century B.C.E. and the 2nd Century C.E. is based in Sāṁkhya philosophy, which adheres to metaphysical dualism. Dualism points to the polarities of existence. On one hand, there is an aspect of the universe that is ever-changing and temporary: prakṛti. This includes the physical stuff of the universe: from mountains and rivers to tables and chairs to human beings – including our brains, flesh, bones, and blood. But prakṛti also includes our minds. Thoughts, mental states, dreams, and emotions are all prakṛti because they are impermanent and ever-changing in nature.

It might sound like everything in the world is prakṛti – what else is there aside from the temporary, changing parts of the world? Dualism reminds us there is another side of the coin. In Sāṁkhya philosophy, there is also an aspect of the world that is permanent and does not change. This is puruṣa and is understood to be the true nature of the self (ātman). This divine nature exists in us all independent of the qualities of the physical world. Puruṣa is considered many in nature; the same non-changing Self unites us all.

The more well-known physical practice of yoga helps us understand this dualism and experience the nature of the true Self. The goal of the three stages of meditation – dharaṇā, dhyāna, and samādhi – is to experience or realize puruṣa and to be able to distinguish that permanent self from the impermanent world. Other aspects of yoga, including the physical practice, āsana, prepare a person for this.

While puruṣa does not act, prakṛti cannot avoid acting since its very nature is to change. Therefore, to choose not to act is an action – it is a choice one makes. The ethics of yoga include a sense of duty with regards to how we act in the world.

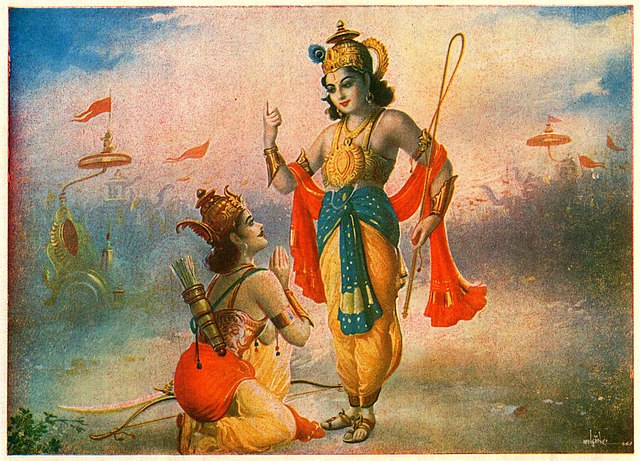

The Bhagavad-Gītā, one of the principal yogic texts, teaches that yoga is “perfection in action” or “skill in actions” (2.50). The perfection or skill here is understood as acting without attachment (without attachment to anything in prakṛti), selfless action where good deeds are done for the sake of the good.

Later chapters of the Gītā give examples of this: to be sincerely generous, one must give without attachments. Giving charitably “to secure some favor in return, or again in expectation of a future reward, or with reluctance” (17.21) or “without proper regard and with contempt” (17.22) are both examples of giving with attachment. However, giving “for the sake of duty alone, given at a proper time and place to a deserving recipient … that is thought to be of the nature of goodness” (17.20).

We see echoes of Aristotle in that very quotation. One Aristotelian virtue is generosity, which is an intermediary between “excess wastefulness and … ungenerosity” (1107b10). Actions are virtuous when they are done “at the right times…toward the right people, for the right end, and in the right way” (1106b21-23).

In yoga, the right reasons are egoless reasons, without attachment. Being attached to prakṛti — the ever-changing world, over which we have little control — is not only self-defeating, it fails to recognize the connected nature of puruṣa. In yoga, we must act for the sake of doing what’s right, out of a sense of duty.

Aristotle says something similar: “Actions done in accordance with virtue are noble and done for the sake of what is noble. So the generous person will give for the sake of what is noble and in the correct way – to the right people, in the right amounts, at the right time, and so on” (1120a24-27).

A key component of living well has to do with intention. In yoga, our actions are noble when they are done with the intention of honoring the divine nature in all beings. That implies particular duties like not lying and not causing harm. Nevertheless, yoga also teaches that it is impossible to live a life without any harm or suffering at all.

In the Bhagavad-Gītā, the protagonist, Arjuna, is told that his duty, as a warrior, is to fight a holy war for the sake of his kingdom. This war is to be fought against his cousins. Arjuna is reluctant to fight at first because of his vow to create no harm, but he soon learns that not fighting would still be a choice—and would create more harm in the world. Fighting is his duty and while it will harm others (his cousins), he must remember that the intention is to protect the vulnerable citizens of the kingdom from his cousins.

The intention behind Arjuna’s action matters greatly: if he chooses to fight for glory, that would not be noble. Yet it is equally not-noble to choose not to fight since that choice is rooted in his attachment to his cousins. Thus, choosing to fight for the sake of the kingdom is to choose to act at the right time and for the right reasons. This is noble and good.

What would Aristotle have said about this? His comments on the virtue of courage are relevant here. Courage, he says, is an intermediary between never acting in the face of danger (being a coward) and acting in any dangerous situation at all (bravado). Courage acts at the right time and for the right reasons and is therefore virtuous. For Arjuna, fighting a war he’s afraid to fight is courageous in exactly that way.

In order to choose virtuous action, Arjuna must have knowledge. The importance of knowledge and the application of reason is another similarity in Aristotelian and yogic texts. Both views teach that in order to live a good life, one must have knowledge about right and wrong. One must then apply that knowledge, making conscious decisions about when it is appropriate to act and how to do so. In other words, one must also use philosophical knowledge to act well.

For Aristotle, knowledge without action is incontinence. For yoga, knowledge without action is impossible since choosing not to act is an action in and of itself. This shifts knowledge without action to knowledge without right action.

Aristotle teaches that to act virtuously, we must act for the right reasons and for the sake of goodness itself. He also cautions us that it is better to act in this way even if the reasons aren’t yet “right”. By acting in the way that a virtuous person would act, by making it “habit”, we will indeed become virtuous. We will come to care about goodness for goodness’ sake.

Yoga also teaches that it is better to give for the wrong reasons than not to give at all. Giving to those in need creates more good and less harm in the world. We can continue to give while working on our attachments at the same time. The practice of yoga helps develop non-attachment. Meditation is a way to remind ourselves of the temporality of the world (prakṛti) and the permanent part of ourselves that connects us all (puruṣa). That knowledge allows us to let go of the desires attached to our actions, purifying them. We can focus on the very general intention of helping others experience less harm, less suffering while in this world.

To be a good yogi and a good Aristotelian involves being aware of the intention behind our actions. It is about developing the “right reasons” for acting. This can be done through the yogic practice of meditation or through active contemplation of the nature of goodness and of harm.

Yoga practice also involves study (Jnana yoga is the yoga of seeking knowledge), meaning one can practice yoga while studying philosophy! Finally, to be a good yogi and a good Aristotelian, one needs to act. It’s not enough to have the right intention and the right knowledge, but we must use that knowledge to act in a way that we create more good and less harm in the world.

Our intentions, knowledge, and actions can all influence the way we approach both the particular yoga ethical principles (yamas and niyamas) as well as the Aristotelian virtues. We can take their shared guidelines of right intention, right knowledge, and right action to help us live better lives.

For example, rather than trying to create no harm (ahimsa in yoga), we can have the intention of less harm or as little harm as possible as we go about our lives. We can make deliberate decisions that respect that. Rather than trying to calculate the perfect amount to give in order to be generous, we can cultivate the intention to give to create more good in the world and then consider – with reason – what is the right charity to which we can give.

Being a good yogi and a good Aristotelian might just boil down to being a good philosopher! Be thoughtful about intentions, consider the choices we have before we act, be deliberate about which choices create more good in the world, and act with the intention of doing what’s right for its own sake. Namaste!

5 comments

One thing puzzles me. You wrote, “For Aristotle, knowledge without action is incontinence.” A quick search gave these definitions for incontinence:

1.

lack of voluntary control over urination or defecation.

“causes of urinary incontinence”

2.

lack of self-restraint.

“the emotional incontinence of modern society”

Neither of these definitions seem to fit. Are you using a different definition, or did you intend a different word?

Absolutely brilliant

Amazing synchronicity, while I was struggling in a non-dual formation , I saw this article and kind of pushed myself to read it ; and amazing It enlightening everything

Now to do the work

Many many thanks

Kathleen Dassier

Hi Isaac, thanks for your comment! ‘Incontinence’ is the world philosophers often use to translate ‘akrates’ and Aristotle writes about this in the Nicomachean Ethics. Here is an entry on the term from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-ethics/#Akra

A quick Google search for Aristotle and incontinence will result with plenty of scholarly work on the topic!

ME HA GUSTADO EL ARTÍCULO

ISIDRO GARRIDO BERMEJO

I have always felt that wisdom speaks across cultures. I don’t believe in dichotomizing between east and west. Yoga and Aristotle, Stoicism and Zen: they all point to the ONE.

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.