Written by Alex Barrientos, Senior Editor, Classical Wisdom

What is the best, the highest, the happiest kind of life for human beings? Does it consist of sensual pleasure, the attainment of money, or finding a meaningful job?

This is just one of the many questions that the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle concerned himself with.

What was his answer to this perennial question? Well, to put it simply, that the happy life is one devoted to contemplation.

The Pursuit of Happiness

Aristotle’s view of the best life rests largely on the notion that the aim of human affairs is happiness, and that the happiest life is one in accordance with what is best in us.

Now, happiness is not some static state to be achieved, but an activity.

In Book I of his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle identifies two types of activities:

- those necessary and desirable for the sake of something else, and

- those that are desired for their own sake.

Happiness, being the aim of human affairs, must belong to the second type of activity.

For an activity to be classified as being desired for its own sake, nothing else must be desired or aimed at beyond the activity itself.

Virtuous actions, for one, seem to be of this kind, “since doing noble and excellent actions is one of the things that are choice worthy because of themselves.” Yet, pleasant amusements—those that indulge the senses—also seem to be of this kind.

But surely, Aristotle thought, pleasant amusements do not provide happiness in the same way that virtuous actions do!

Pleasant amusements may seem to be desired for themselves because people often choose them in spite of the harms that result.

Furthermore, people often consider those who delight in pleasant amusements to be happy, “because people in positions of power,” namely tyrants, “spend their leisure in them.”

But we are wrong, Aristotle argues, to value the opinion of such people.

That tyrants and others in positions of power value pleasant amusements is no surprise, for, “being unable to taste pure and free pleasures,” they instead “take refuge in the bodily ones.”

In any case, as Aristotle notes, “virtue and understanding, which are the sources of excellent activities, do not depend on holding positions of power.”

Along with that response, Aristotle provides three other reasons as to why pleasant amusements are not to be confused with happiness:

- Pleasant amusements are not, in fact, desired for themselves. Pleasant amusements are a sort of relaxation from work and, because we cannot work endlessly, we require relaxation. Thus, pleasant amusements, being a type of relaxation from serious activity, such as work, are not desired for their own sake but for the sake of such activity.

- Happiness, as has been said, “seems to be in accord with virtue,” but virtue “involves engagement in serious matters and does not lie in amusement.” What is serious is better than that which involves amusement, and the better activity is also the more excellent. Since what is serious is better and therefore more excellent, “it bears more of the stamp of happiness.”

- Anyone can enjoy pleasant amusements and other bodily pleasures. Even slaves, Aristotle tells us, can enjoy such amusements. Yet no one would venture to attribute happiness to the slave who partakes in these amusements. This is due to the fact that “happiness does not lie in such pastimes but in activities in accord with virtue.”

The Divine Within Us

With happiness now disassociated from pleasant amusements and placed instead in accord with virtue, Aristotle argues that happiness must be in accord with the highest virtue.

The highest virtue must involve the element that is best in us. What is best in us—what is most divine—according to Aristotle, is the understanding, or reason. It is the understanding that distinguishes human beings from other animals. The understanding may either be considered divine or as being the most divine thing within us. In either case, “the activity of it, when in accord with the virtue that properly belongs to it, will be complete happiness.” And this activity, according to Aristotle, is contemplative activity.

Aristotle’s argument as to why the activity of the understanding—contemplative activity—will be complete happiness, is because the attributes assigned to happiness are the same attributes assigned to contemplative activity.

Like happiness, contemplative activity is the most excellent, the most continuous, the most pleasant, and the most self-sufficient activity. Furthermore, contemplative activity, like happiness, is loved for its own sake and involves leisure.

Contemplative activity is the most excellent because the understanding is the most excellent element in us and because, “of knowable objects, the ones the understanding is concerned with are the most excellent ones.”

It is the most continuous activity because we can pass our time in contemplation more continuously than in other activities.

It is the most pleasant activity because the pleasures it entails, those that are derived from philosophy and theoretical wisdom, are of a pure and enduring nature and because “those who have attained knowledge should pass their time more pleasantly than those who are looking for it.”

It is the most self-sufficient activity because, though even the philosopher or “theoretically-wise person” requires the necessaries of life, he/she does not need others in order to engage in contemplation; though they may of course benefit from the company of others, one can contemplate in solitude.

Contemplative activity is loved for its own sake, “For nothing arises from it beyond having contemplated.”

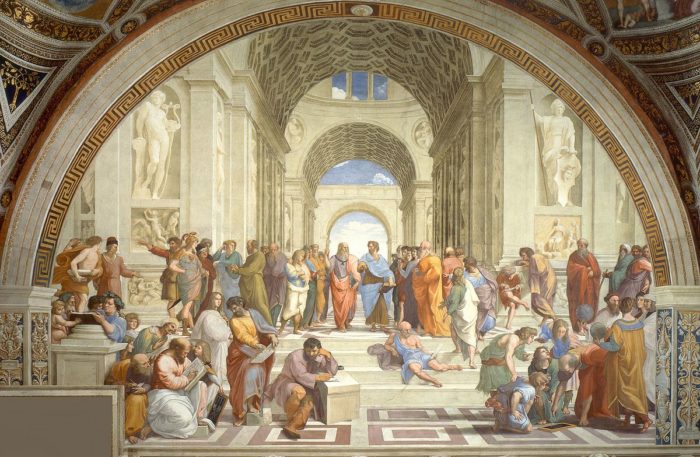

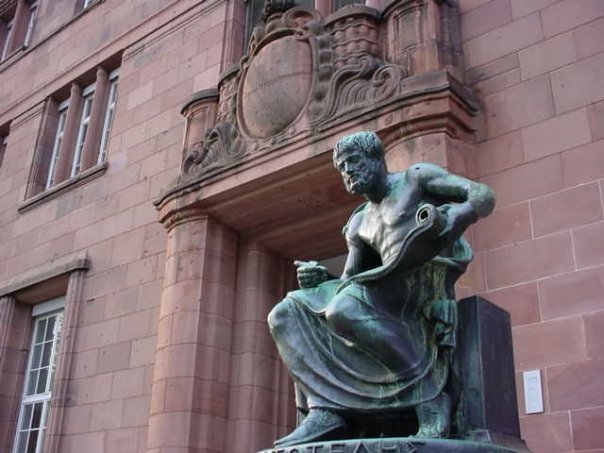

Fig. 7 Wallerant Vaillant, after Raphael, Plato and Aristotle, 1658–77, mezzotint Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. RP-P-1910-6901 (artwork in the public domain)

Finally, contemplation, like happiness, involves leisure. However, not leisure in the sense of lounging around. It is serious, it involves activity, it involves a rigorous dedication of the mind to study.

Dear to the Gods

But someone might be skeptical and object that the contemplative life is too high to attain for human beings. Perhaps it is a life only fit for the gods!

Yet, the element of the understanding is divine, or is at least the most divine element within us. Thus, according to Aristotle, there is no excuse to concern ourselves only with human and mortal things. We should, instead, “as far as possible immortalize, and do everything to live in accord with the element in us that is most excellent. For even if it is small in bulk, in its power and esteem it far exceeds everything.”

So, we should not let the enormity of the task deter us. It is our happiness—true happiness—that is at stake!

“Now he who exercises his reason and cultivates it seems to be both in the best state of mind and most dear to the gods. For if the gods have any care for human affairs, as they are thought to have, it would be reasonable both that they should delight in that which was best and most akin to them (i.e. reason) and that they should reward those who love and honour this most, as caring for the things that are dear to them and acting both rightly and nobly. And that all these attributes belong most of all to the philosopher is manifest. He, therefore, is the dearest to the gods. And he who is that will presumably be also the happiest; so that in this way too the philosopher will more than any other be happy.” ~ Nicomachean Ethics, Book X, ch. 8

Perhaps such a life is difficult if not impossible for human beings to attain. Yet, with Aristotle, we should respond that, we must “do everything to live in accord with the element in us that is most excellent.” And, along with the seventeenth century philosopher Benedict de Spinoza, we should acknowledge that, “all things excellent are as difficult as they are rare.”

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.