by Kevin Blood

“Stranger, you would do good to stay awhile, for here the highest good is pleasure…”

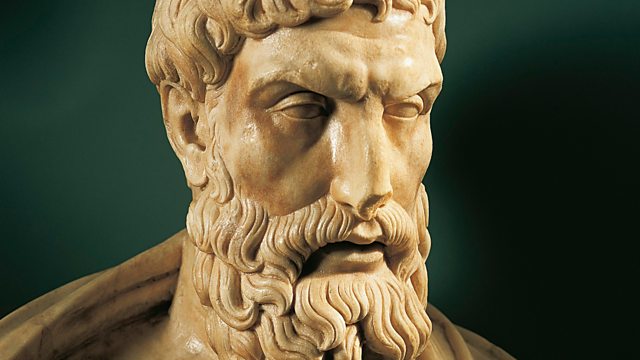

According to Seneca the Younger, these words could be seen at the entrance to the philosopher Epicurus’ garden in Athens. It was a place of seclusion, where, with a small group of friends, Epicurus taught and lived out his philosophy. But what was his philosophy, exactly?

During Epicurus’ life, his teachings grew in popularity, becoming one of the dominant philosophies of the age. He was a polymath. He covered diverse subjects, from ethics to biology. Epicureanism reached its zenith around 70 B.C. While popular in Rome, it faced criticism. Its teachings countered the Roman virtue of piety (pietas), the carrying out of all one’s obligation to the family and the gods, and ancestral custom (mos maiorum). Its emphasis on withdrawal from public life flew in the face of the Roman political system, where patricians were encouraged to follow the ‘ladder of office’ that an aspiring politician was expected to climb, handing out benefits and bribes to friends and clients as they rose.

For some ancient commentators, Epicurus’ views on the gods and the soul were problematic, and they proved the same for Christian scholars, who thought Epicurus’ views heretical. The Epicurean view? Simply put, when we come to a true understanding of the gods, we can conclude that they do not exist, or if they do, that they are indifferent to us. For Epicurus the soul is mortal. He insists on materialist empiricism and his naturalistic, evolutionary, ideas about the formation of the world and the development of human societies cannot be reconciled with many religious teachings. For his heresy, Epicurus can be found in Dante’s Sixth Circle of Hell.

Bad press from ancient and medieval opponents of the philosophy, and skimming of its basic principles, play a part in the idea that Epicureanism is common hedonism, the self-centred and short-term pursuit of sensual pleasures, regardless of consequences. This reading of Epicurus’ teachings is reductive and misleading.

Epicurus teaches pleasure is the supreme good. We should seek pleasure to achieve a good and happy life of good spirits (eudaimonia). Genuine pleasure, for Epicurus, involves the elimination of fear and pain. This is achieved by having enough food, a comfortable living situation, tranquil relationships, close friends, and the practice of moderation.

Epicureanism divides pleasure into two kinds. Active pleasure (kinetic pleasure) is felt when satisfying a desire or removing pain. For example, eating when hungry. Static pleasure (katastematic pleasure) comes from contentment or tranquility. For example, feeling full and satisfied after eating. These pleasures manifest in physical and mental forms. The physical? Freedom from things like hunger, thirst, or ill-health. The mental? Freedom from negative thoughts, like fear and worry. Freedom from physical disturbance is aponia and liberation from mental disturbance is ataraxia. Epicurus has time for kinetic pleasures, but they are short-lived, so he places greater emphasis on the benefits of katastematic pleasures, which last longer.

Epicurus differentiated between physical and mental pleasure and pain. Physical pains are fleeting and encompass only the present. Mental pains endure and can encompass the past (like pleasant reminiscences or regretting poor decisions) and the future (like confidence or doubt about what may happen).

Because katastematic pleasures concern the meeting of desires and the relieving of fears, Epicurus clarified and sorted the types of desire we experience by dividing them into three groups: Natural and necessary, natural and unnecessary, and unnatural and unnecessary (the vain desires).

The first is to be sought after, we should be receptive but wary of the second, and the third should be avoided.

Natural and necessary desires, like the need for food, water, comfortable shelter, and human companionship, are hard to get rid of, but simply satisfied, giving pleasure when they are. They are necessary for life, and for a happy life, we must meet these desires. In satisfying them we reach aponia.

For Epicurus, natural and unnecessary desires, like fine food, designer clothes or sex, are not necessary for life, and are not always easily satisfied. These are kinetically pleasurable; yet they offer a katastematic risk: the greater the indulgence in these pleasures, the more habitual their consumption becomes. If they are unavailable, we risk losing peace of mind because of an inability to fulfil an inessential desire. Epicurus’ advice is to be open to these desires, but to try to not become used to them.

Unnatural and unnecessary desires are things like a lust for power, wealth and fame, the vain desires. Epicurus teaches us these desires are not natural to human beings. We are molded by society to want them, they are unnecessary and hard to satisfy, and without natural limits. Think of the person who relentlessly pursues power. No amount of power will satisfy them because it is always possible to get more and when they get more they fear losing it. They gain mental anguish, and the anger and enmity of those around them, who become envious. For Epicurus, these desires are unnecessary and unnatural. They cannot be satisfied, they lead to pain and fear, and they should be avoided.

Epicurus’ advocation of simple living is not to be followed too stringently. He was no puritanical ascetic, denying material possessions and pleasures in favour of spiritual ends, nor was he an insatiable hedonist, pursuing all pleasures regardless of the cost. For Epicurus, sources of pain are to be minimized. The object is not to get rid of all sources of pleasure or all physical possessions. If getting rid of something brings more pain than it alleviates, it is counter-productive in achieving a good and happy life. Further, most kinetic pleasure is achieved in the process of satisfying our basic needs. Luxuries, though pleasant, bring little additional value. Moderation relative to oneself is the key.

“There is also a limit to simple living, and he who fails to understand this falls into an error as great as that of the man who gives way to extravagance.”

-Epicurus

When people think of the practice of moderation it often takes the form of a bossy and prudish moralism, the directive being not to indulge in ‘bad’ things and behaviours. For Epicurus, moderation cuts both ways, one can have too much of a pleasurable thing too often and one can have too little not often enough.

Think of someone at a lavish dinner party, they can drink too much wine and eat too much fine food too quickly, get drunk rapidly, get sick, have to leave friends and leave the party early, miss out on a pleasurable, sociable, evening, and the hangover the next morning brings pain. Epicurus would advise this be avoided.

On the other hand, they can eat and drink too little too slowly, remain hungry, not experience a pleasurable and longer-lasting katastematic buzz of feeling just full enough and merry, and with that miss the loosening of inhibitions that can lead to fun and interesting conversation. The result is similar, minus the hangover. Epicurus would advise this should be avoided.

The goal is to reach aponia and ataraxia often enough and to make it last long enough so there is a continuous flow of pleasure without intervals of pain, then we can achieve eudaimonia. For Epicurus, on the physical level, finding the middle-ground relative to oneself is a part of reaching a long-lasting state of ataraxia. The ideal Epicurean dinner party? These happen frequently: close friends, free from fear and worry, gather. There is enough good food and drink for all, and all partake of it with moderation relative to themselves. Good times! You will notice that the absence of fear and worry make it the ideal Epicurean dinner party.

Satisfying our natural desires is insufficient to reach ataraxia and have atranquil mind. The removal of mental anguish and worry is a must. Therefore, for Epicurus, to attain ataraxia we should not fear death or the gods. Not to fear death because we are not conscious of it when it happens, and the gods because it is unlikely that they pay attention to human affairs. The Roman poet Lucretius quotes Epicurus:

“Death is nothing to us. When we exist, death is not; and when death exists, we are not. All sensation and consciousness ends with death and therefore in death there is neither pleasure nor pain. The fear of death arises from the belief that in death, there is awareness.”

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.