By Alex Barrientos, Associate Editor, Classical Wisdom Weekly

Being lovers of Classical Wisdom, you are likely familiar with Epicurus and his school of thought. His remedies to deal with the fear of death, his description of what the blessed life consists of, and his praise of friendship, among other things, makes him a lovable figure in the history of philosophy.

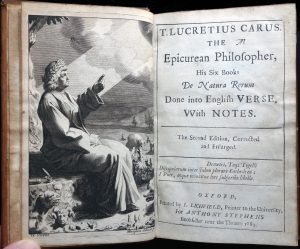

Titus Lucretius Carus (~94-50 BCE), slightly less well known, is responsible for carrying on the torch of Epicureanism into the Roman world. The teachings and maxims of Epicurus were preserved by Lucretius in his philosophical poem On the Nature of Things (De Rerum Natura). In this work Lucretius captures not only the Epicurean approach to life but also explains the Epicurean approach to studying the natural world, as well as the underlying metaphysical and epistemological views that formed the Epicurean method of inquiry.

Lucretius also had some advice to offer on love. Now, you might be wondering, what could an ancient Roman philosopher-poet have to say about love that would be of any relevance to us today? Well, plenty as it turns out… in fact, reading this back in high school might have saved me a lot of troubles!

Origins of Love

According to Lucretius, the body is the source through which the “mind is pierced by love.” Think, for instance, of how the wounded person falls “in the direction of their wound”, how the “blood spurts out towards the source of the blow”, and how the “enemy who delivered it, if he is fighting at close quarters, is bespattered by the crimson stream.” Similarly, Lucretius tells us, when someone is “pierced by the shafts of Venus”, that person “strives towards the source of the wound and craves to be united with it and to transmit something of his own substance from body to body. His speechless yearning is a presentiment of bliss.” This yearning, this striving to be united with the source of the wound, is the very origin of love — “that drop of Venus’ honey that first drips into our heart, to be followed by numbing heart-ache.”

So, basically, love hurts, because we love what hurts us.

Viewing the body as the source of love makes sense too when we reflect on how much the feeling of love impacts the body. Think of those early days when love first sparks; how we feel “butterflies” in our stomach, how our heart starts racing, how we blush and even sweat in the sight of the object of our love. Further reflections like these suggest that Lucretius is right, that the experience of love is not entirely a mental experience, it is one that is very much rooted in the body.

The Bitterness of Love

From the very heart of the fountain of delight there rises a jet of bitterness that poisons the fragrance of the flowers.

Though we are apt to think of love in positive terms, Lucretius did not have so rosy a view of it. According to Lucretius, love is insatiable, accompanied by pain, heart-ache, bitterness, and other mental disturbances. Love, he tells us, “is the one thing of which the more we have, the more our breast burns with the evil lust of having.” Whereas we can satisfy hunger and thirst by eating and drinking, the cravings of love are only multiplied.

Even when love comes to fruition, in the moment of lovemaking, all is in vain:

Then comes the moment when with limbs entwined they pluck the flower of youth. Their bodies thrill with the presentiment of joy, and it is seed-time in the fields of Venus. Body clings greedily to body; moist lips are pressed on lips, and deep breaths are drawn through clenched teeth. But all to no purpose. One can glean nothing from the other, nor enter in and be wholly absorbed, body in body; for sometimes it seems that that is what they are craving and striving to do, so hungrily do they cling together in Venus’ fetters, while their limbs are unnerved and liquefied by the intensity of rapture. At length, when the spate of lust is spent, there comes a slight intermission in the raging fever. But not for long. Soon the same frenzy returns. The fit is upon them once more.

This passion of lovers, this passion that cannot be satiated, is “storm-tossed, even in this moment of fruition, by waves of delusion and incertitude.” Delusion perhaps about what that moment might be like, what it might feel like, perhaps deluded by the façade the lover put on; Uncertain of one’s own performance, uncertain of one’s own feelings or the feelings of the lover. And, thinking delusion and incertitude might dissipate with the climax, there is instead only “a slight intermission in the raging fever” before it comes roaring back.

Nor does it end with the carnal aspect of love. Indeed, the curse continues even in the absence of the lover. As Lucretius puts it, “Though the object of your love may be absent, images of it still haunt you and the beloved name chimes sweetly in your ears.” And then there is the bitterness that arises in the presence of the lover. Lucretius writes,

Perhaps the beloved has let fly some two-edged word, which lodges in the impassioned heart and glows there like a living flame. Perhaps he thinks she is rolling her eyes too freely and turning them upon another, or he catches in her face a hint of mockery.

That the beloved can say something that stings in a way that no words from another could, and that insecurities arise in our minds concerning the beloved that don’t arise in the presence of others, are just some of the many bitter aspects of love.

Baby Don’t Hurt Me

Whether it is the infirmities of mind that arise during lovemaking, in the absence of the beloved, or even in their presence, these are only the “evils inherent in love that prospers and fulfills its hopes.” How much more apparent, then, are the evils that accompany “starved and thwarted love.”

Thus, Lucretius advises us to avoid the passions of love altogether:

Thrust from you anything that might feed your passion, and turn your mind elsewhere. Vent the seed of love upon other objects. By clinging to it you assure yourself the certainty of heart-sickness and pain.

This might seem a bit extreme. However, given the pains that are inherent in love, according to Lucretius, it makes sense that he would caution us against it. It is also the case, he thinks, that avoiding the snares of love is easier to do then to break free once you are enmeshed. We must be on our guard beforehand.

But not all hope is lost for those of us whose hearts have already tasted Venus’ honey! For, “be you never so tightly entangled and embrangled, you can still free yourself from the curse unless you stand in the way of your own freedom.” What can we do to break free of the curse? This is where Lucretius begins to offer what can, I think, be rightfully termed as break-up advice.

The first method of getting over our beloved is to,

Concentrate on all the faults of mind or body of her whom you covet and sigh for. For men often behave as though blinded by love and credit the beloved with charms to which she has no valid title.

I am sure we can all, men and women alike, think of things we attributed to the mind or body of past loves that, in retrospect, we came to see as attributes not truly belonging to the person. Whether it was honesty, beauty, intelligence, humor, kindness, wit, etc., we have likely reflected on past relationships and thought, “Why on earth did I ever think my beloved ever was any of those things?” Following these reflections we might feel a sense of regret or shame for being duped. Yet these are exactly the type of delusions that love inherently brings with it. If we keep these disappointments in mind regarding those we desire, and those we once desired but sigh over now, we can both avoid future pains and overcome present ones.

If that doesn’t work, well, Lucretius tells us, we are to remember that there are others, that there was a time in life where we carried on fine without the beloved before, and that the beloved shares much in common with others of their sex. Or, as Lucretius put it,

Even so, there are still others. Even so, we lived without her before. Even so, in her physical nature she is no different, as we all know, from the plainest of her sex.

In modern terms: there’s other fish in the sea! So cry me a river, build a bridge, and get over it!

Well, you get the point.

But perhaps, dear reader, you find all this unsatisfying. After all, is love really so terrible? Sure, sometimes we experience the terrible things Lucretius speaks of, but there are also aspects of love that outweigh all that. Is it not only certain types of love, perhaps not even deserving of the title, that carry with them these pains? Yet, even when love is accompanied by such things, even when we feel crushed under the weight of grief, do we not still hold that it is better to have loved and lost than to have never loved at all? Sure, it might sound nice to avoid the heart-ache in the first place, but then we would be missing out on all the beauties that love has to offer us as well!

As mentioned above, I’ll leave its relevance up to you, dear reader. But however you feel after reading these love tips from Lucretius, it is humbling to reflect on the fact that someone who set out to understand the nature of the universe, stopped along the way to understand the nature of love.

2 comments

nonsnsical prescription to a common malady. First understand yourself and see yourself as you really are. Then do the same with her.

Philosophy plays a huge role when we are talking about any type of love. I don’t get why there is huge hate towards this domain. After all, we are all using something from a different philosophy without realizing that we are doing that. Books are our friends when it comes to any kind of hard times. Recently I’ve discovered that some articles can be useful as well. For example, this one https://breakupangels.com/how-to-help-friend-through-breakup/. I must admit that there cannot be a term of comparison, but you can find some solid advice if you know where to look. Sometimes, the answer is right in front of you. You just have to see it

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.