By Andrew Rattray

At first glance, the philosophies of Stoicism and Cynicism appear to be two sides of the same coin. Both philosophies are eminently practical, designed as day-to-day practices more than grand ideals, focusing on achieving a state of ‘eudaimonia’ (literally, ‘good spirit’), a state of flourishing and freedom from worry, through self-discipline, sacrifice, and internal reflection. These similarities were also noted by contemporary figures, for example in Juvenal’s Satires (number 13) he jests that the only difference between the Stoics and the Cynics is that the former wear shirts!

I suppose this isn’t surprising given that they share a common history, both stemming ultimately from the teachings of Socrates. In fact, one of the earliest and most prominent Cynic philosophers, Diogenes of Sinope, went on to mentor Crates of Thebes, who in turn mentored Zeno of Citium, widely considered the founder of Stoicism.

Ultimately, the two philosophies follow the same basic principle; that the key to happiness is to live in accordance with nature. Both posit that humanity has been gifted with the power of rational thought and that through this rationalism we can strive toward the state of ‘eudaimonia’ by not allowing oneself to be controlled by external factors. However, while both philosophies might start their adherents down a similar path, it soon forks, and you will find that in practice the two differ considerably.

Where the differences start to emerge is in what each philosophy considers to be ‘in accordance with nature’. You see, the Stoics believe that human beings naturally tend toward both ensuring their own success, but also living in harmony with others, and so Stoicism promotes temperance within these natural desires. Stoics believe it is acceptable to wish for wealth, for example, provided one does not damage their virtue in its pursuit, and that it is acceptable to live within the confines of societal expectation, provided that those expectations are just and, once again, do not diminish one’s virtues as an individual.

The Cynics on the other hand placed a far greater value upon one’s personal nature, individual freedom, and self-sufficiency. Interestingly, the name ‘Cynic’ comes from the ancient Greek ‘kunikos’ meaning ‘dog like’. The moniker has many motivations, but it was initially seen to be an insult to Cynic adherents who would often live on the streets like stray dogs, with some even surviving on begging alone. This may seem extreme, but through this process they could not only free themselves of the burdens of materialism, but moreover, by standing apart from societal systems, they were better placed to realise how these systems can lead us away from living in accordance with our true nature and experiencing real freedom and happiness.

This, I feel, is the key difference between the Cynics and the Stoics. Where the Stoics believe that a good life can be achieved within certain confines of human desires and societal expectations, the Cynics argue that true happiness cannot be achieved without freeing oneself from all limitations, including those imposed by our internal wants, as well as other people.

For example, the Cynics reject any ideas of wealth or grandeur outright; arguing that we do not need such luxuries to live naturally; claiming that not even a home, or a bed, are truly necessary. The Stoics on the other hand agree that these things are not necessities but argue that things such as a warm bed or a nice home bring with them certain benefits and that it’s okay to utilise these benefits. In a nutshell, the Stoics recognise that these sorts of luxuries don’t inherently make you happy, but they can make life easier, and so they accept their place in our lives, whereas the Cynics reject these things regardless of their uses precisely because they don’t make us happy directly.

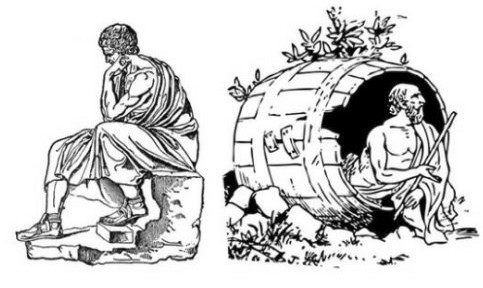

The differences in the outlook of the Stoics and Cynics are made even more stark when we contrast two of the most famous adherents of each philosophy; the Stoic Marcus Aurelius, and the Cynic Diogenes of Sinope.

As many of you know, Marcus Aurelius was a much-lauded Roman Emperor who earned a reputation as a ‘philosopher king’ among historians. In fact, he was described by Herodian of Antioch as “Alone of the emperors, he gave proof of his learning not by mere words or knowledge of philosophical doctrines but by his blameless character and temperate way of life.”. Marcus Aurelius’ personal journals have formed the collection now commonly known as the Meditations.

On his approach to social life, he wrote “When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: the people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous and surly. They are like this because they can’t tell good from evil. But I have seen the beauty of good, and the ugliness of evil, and have recognized that the wrongdoer has a nature related to my own – not of the same blood and birth, but the same mind, and possessing a share of the divine. And so none of them can hurt me. No one can implicate me in ugliness. Nor can I feel angry at my relative, or hate him. We were born to work together like feet, hands and eyes, like the two rows of teeth, upper and lower. To obstruct each other is unnatural. To feel anger at someone, to turn your back on him: these are unnatural.”

As with other Stoics, Marcus Aurelius accepts that although the people he interacts with may have a negative influence he realises that through his own self-control he can negate this, and that this is in fact a natural way of living, since we are ‘born to work together’.

Diogenes of Sinope, on the other hand, stands in abject contrast with the legacy of Marcus Aurelius, despite their equal adherence to their respective philosophical practice. He was one of the most infamous philosophers of his time and is still widely known today for his extreme behaviour. While Marcus Aurelius was known as ‘the Philosopher’, Diogenes’ moniker was ‘the Dog’. This was, of course, originally intended as an insult but Diogenes seemed to take great pleasure in the jest. In fact, he is quoted by the historian Diogenes Laertius in his work ‘The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers’ as responding, when asked why he was called ‘the Dog’, “Because I fawn upon those who give me anything, and bark at those who give me nothing, and bite the rogues”.

Where Marcus Aurelius was an emperor, Diogenes lived a life of poverty, despite being the son of a well-off banker, he chose to abandon his possessions and lived in a large ceramic pot in the marketplace of Athens. While Marcus Aurelius did much to improve the lives of Roman citizens through legislative action and saw benefits in working together with others, Diogenes would debase the morals and rules of society to point out hypocrisies. Many different historians, such as Dio Chrysostom and Diogenes Laertius, attest that Diogenes would urinate on people he didn’t like, defecate in the theatre, and masturbate in public, all in an effort to demonstrate how social expectations were limiting our freedom.

Indeed, Diogenes lived a life of voluntary adversity by choosing to comport himself in such a confrontational manner. However, despite this adversity some later Stoics, such as Epictetus, considered him to be living in total freedom. Diogenes did what he wanted, when he wanted, and from all we can glean from contemporary texts he was perfectly happy doing so. In no way is this better illustrated than in his conversation with Alexander the Great. Although the validity of the accounts of their meeting have been questioned, both Diogenes Laertius and Plutarch recount the story. Alexander is said to have found Diogenes, excited to meet such a famed philosopher, and offered if he could offer any favour Diogenes need only name it. Diogenes replied simply “Stand out of my sunlight.” .

It’s almost impossible not to be a little jealous of this carefree attitude. How many times have you wished you could tell your boss how you really feel? How many times have you gotten frustrated at being told you can’t do something simply because it’s ‘frowned upon’? But is it a freedom you truly desire, or just a vanishing craving to set the world to rights? Might it not be better to live as Marcus Aurelius did, with a well-measured and tempered response to the adversities in our lives?

While the comparison between the likes of Marcus Aurelius and Diogenes of Sinope is an extreme one, it does help to demonstrate not just the key differences between the Stoics and the Cynics, but also the different perceptions of the two philosophies in practice. Marcus Aurelius, and the Stoics more generally, accepted the benefits of some luxuries and a life lived in harmony with others, whereas Diogenes, and the Cynics, rejected the trappings of wealth and excess and focused instead on their individual freedom, in some cases at the expense of others. Both philosophies believe freeing oneself from external influence is the key to a good life, but the Stoics believe that one can enjoy certain aspects of life without allowing them to influence you.

Though the development of the two philosophies is deeply intertwined I think it is fair to say that the Stoics refined and tempered many of the tenets of Cynic philosophy into a practice that found more mainstream acceptance whilst still promoting the inward focus on virtue and wisdom as being key to reaching a state of eudaimonia. However, the Cynics paved the way, bringing much of these shared ideals of austerity and forbearance from temptation into the public consciousness. Without the Cynics, there could be no Stoicism, but without the Stoics, the wisdom of such irksome characters as Diogenes may well have been clouded in their extremely oppositional approach to the world and lost to the ages.

One comment

I am sorry bit the author’s depiction of both is off base. Cynics are stoics who accept bad outcomes as normal. There is no other difference.

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.