Written by Alex Barrientos, Associate Editor, Classical Wisdom

Stoicism, as a philosophy of life, has become increasingly popular amongst the general public.

With practical lessons on how to control our temper, how to have good friendships, prioritizing what’s important, facing death, avoiding the pitfalls of consumer culture, and how to live the good life, it is no surprise that Stoicism would have much to offer those of us living in the 21st century.

I myself have improved much in my life due to my readings of Epictetus, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius.

Though there is some excitement at this reemergence of Stoicism, there is room for concern as well. Excitement, because there is indeed much that the Stoics said that can and should be applied in our daily lives; concern, because perhaps behind this reemergence is the fact that people are feeling less and less in control of the world around them.

In the political realm, for instance, the feeling that “my individual actions won’t make a difference anyways” is becoming more widespread, especially amongst youths who notoriously fail to turn out to vote as it is.

This feeling is, of course, a self-fulfilling prophecy: if you believe you can’t make a difference anyways, and so don’t do anything at all, you will, in fact, not make a difference… shocking!

Whether all individual actions in the political realm really make a difference or not, and to what extent they make a difference is beside the point; it is not some well-reasoned, statistical analysis that leads people to feel this way, but the feeling of impotence itself.

They emphasized what they sometimes referred to as a retreat into the self. In other words, focus on what’s in your power and be indifferent toward what is not. All that is in our power are our thoughts and actions and, even in the case of being physically restrained, they argued, a free mind is never in chains.

“Of all existing things some are in our power, and others are not in our power. In our power are thought, impulse, will to get and will to avoid, and, in a word, everything which is our own doing. Things not in our power include the body, property, reputation, office, an, in a word, everything which is not our own doing.”

This is, on the surface and for the most part, helpful advice for many people. In our modern world we do often get tossed about too much: bombarded by social media and television, concerned about having the latest technology, running to the stores to buy the latest fashion.

These are all things which the Stoics thought cause us much inner tumult and which we should be far less concerned with. Their main concern was with living a tranquil and virtuous life, and they saw focusing too much on external things as inherently opposed to tranquility and virtue.

Here are just several examples of some of the advice the Stoics had to offer:

“What disturbs men’s minds is not events but their judgments on events… And so when we are hindered, or disturbed, or distressed, let us never lay the blame on others, but on ourselves, that is, on our own judgments.” Epictetus, Enchiridion, 5“Ask not that events should happen as you will, but let your will be that events should happen as they do, and you shall have peace.” Enchiridion, 8

“What difference does it make how many masters a man has? Slavery is only one, and yet the person who refuses to let the thought of it affect him is a free man no matter how great the swarm of masters around him.” – Seneca, Letter XXVIII, Letters from a Stoic“…how pleasant it is to ask for nothing, how splendid it is to be complete and be independent of fortune.” Letter XV“Everything hangs on one’s thinking” Letter LXXVIII“A man is as unhappy as he has convinced himself.” Letter LXXVIII“Remove the judgment, and you have removed the thought ‘I am hurt’: remove the thought ‘I am hurt’, and the hurt itself is removed.” Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, Book 4:7“Withdraw into yourself. It is in the nature of the rational directing mind to be self-content with acting rightly and the calm it thereby enjoys.” Book 7:28“If your distress has some external cause, it is not thing itself that troubles you, but your own judgment of it – and you can erase this immediately.” Book 8:47“That all is as thinking makes it so – and you control your thinking. So remove your judgements whenever you wish and then there is calm…” Book 12:22

As we can see from these passages, much of what the Stoics had to say was often deeply inspiring and memorable. They are the type of sayings that you keep with you throughout your life. But the underlying assumption the Stoics made—their stark distinction between what is and is not in our power—can, and often does, lead people to apathy and seems in some cases to provide an excuse for those who feel they have no obligation to be concerned with the state of society or political matters.

Furthermore, and this is the heart of the concern, in a political climate where people feel helpless and powerless as it is, Stoicism becomes a philosophical justification for inaction and retreating into the self.

Stoicism seems to reveal itself as a practical philosophy when it is no longer practical or no longer feels practical to change the things around us. Striving to change the things we can no longer accept gives way to accepting the things we cannot change.

But what we can and cannot change, what depends and what does not depend on us, and what is and is not in our control are difficult lines to draw.

The Stoics, Simone de Beauvoir thought, were at least right in acknowledging that we are not oppressed by things. As she wrote,

“[M]an is never oppressed by things; in any case, unless he is a naïve child who hits stones or a mad prince who orders the sea to be thrashed, he does not rebel against things, but only against other men.”

She continues,

“Certainly, a material obstacle may cruelly stand in the way of an undertaking: floods, earthquakes, grasshoppers, epidemics and plague are scourges; but here we have one of the truths of Stoicism: a man must assume even these misfortunes, and since he must never resign himself in favor of anything, no destruction of a thing will ever be a radical ruin for him, even his death is not an evil since he is man only insofar as he is mortal: he must assume it as the natural limit of his life, as the risk implied by every step.”

Indeed, this is one of Stoicism’s greatest strengths. Some of the most beautiful and useful passages the Stoics have to offer are on accepting the natural limits of life and the things that are out of our control.

Yet, if we have established that the natural world and the limits set on us by nature do not oppress us, and furthermore that we must learn to accept these events and limitations rather than thrash the sea, what is it, then, that we should concern ourselves with?

What can, in fact, oppress us and deserve to be given our attention, maybe even our resentment and hatred?

“Only man can be an enemy for man,” de Beauvoir writes,

“It is here that the Stoic distinction between ‘things which do not depend on us’ and those which ‘depend on us’ proves to be insufficient: for ‘we’ is legion and not an individual; each one depends upon others, and what happens to me by means of others depends upon me as regards its meaning; one does not submit to a war or an occupation as he does to an earthquake: he must take sides for or against, and the foreign wills thereby become allied or hostile. It is this interdependence which explains why oppression is possible and why it is hateful.”

Second thoughts … Simone de Beauvoir at home in 1957.

Photograph: Jack Nisberg/Sipa Press/Rex Features

In other words, our interdependence on others interferes with any Stoical distinction between things that do and do not depend us; in our relations with others, all depend on us and we depend on all. Oppression by our fellow human beings is not some natural order of the world that we must assent to; the tyrant who rides into town declaring himself ruler is not akin to a flood or an earthquake, and thus need not be accepted as such.

Hegel also had a critique of Stoicism which gets even more at the heart of my concern. As noted so far, the Stoics praised an inward freedom, a retreat into the realm of thought and individual action. Herbert Marcuse, quoting Hegel, explains that,

“‘The essence of this [Stoic] consciousness is to be free, on the throne as well as in fetters, throughout all the dependence that attaches to individual existence…’ Man is thus free because he ‘persistently withdraws from the movement of existence, from activity as well as endurance, into the mere essentiality of thought.’”

As Marcuse explains, Hegel did not view Stoic freedom as real freedom, but rather as “the counterpart of ‘a time of universal fear and bondage.’” This analysis is important, and can help partially explain the reemergence of stoicism. It is no coincidence, Hegel would argue, that as wealth, and thus power, have become concentrated into fewer and fewer hands, many have turned to a philosophy that encourages retreat from the external world.

Be indifferent to that which is indifferent; only your own thoughts and actions are within your control, therefore that is all you should concern yourself with; accept all that happens to you since it is not under your control. What philosophy conforms more perfectly to the feeling of impotence in modern democratic societies? What surprise, then, that it should become so popular.

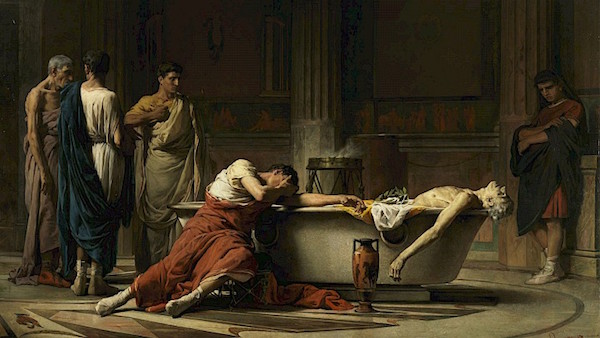

We cannot entirely blame this failure entirely on the Stoics themselves, since all philosophical thought is situated within a certain time and place. And though it is a rather unfair criticism to accuse Stoicism of leading to political apathy (considering that many of the Stoics themselves, notably Marcus Aurelius and Seneca, lived very political lives), encouraging people to only focus on what is under their control—defining that as being simply our own thoughts and actions—can have an apathetic effect.

What is and is not in our control is blurrier today than it was for those living under the aristocracies, oligarchies, dictatorships, and slave societies of ancient Rome and Greece. This aside, as I mentioned above, some of the finest lessons and teachings undoubtedly can be found amongst the writings of Aurelius, Seneca, and Epictetus. I myself have been profoundly impacted by their words. But we are not without justification to pause and wonder: why now? Perhaps the rise of stoicism will be a positive thing. But perhaps Hegel is right, that it is also indicative that we are living in “a time of universal fear and bondage.”

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.