Written by Mariami Shanshashvili, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Not many historical events in the annals of our civilization are so universally well-known that they need no introduction. The death of Socrates is one such momentous event.

An unfading scene firmly entrenched in all our minds; for most of us, dictated by the iconic painting of Jacques-Louis David: grey-haired, bolt upright Socrates, ringed round with a circle of his closest disciples and friends, adamantly holding up the fatal Hemlock cup, and having his last words uttered, readily facing his death with phenomenal equanimity.

However, the Ancient World was witness to the suicide sentence of another great philosopher: a scene no less soul-stirring, but far less fixed in memory. 456 years after Socrates’ death, Emperor Nero ordered his aged tutor and advisor, Lucius Annaeus Seneca, to take his own life.

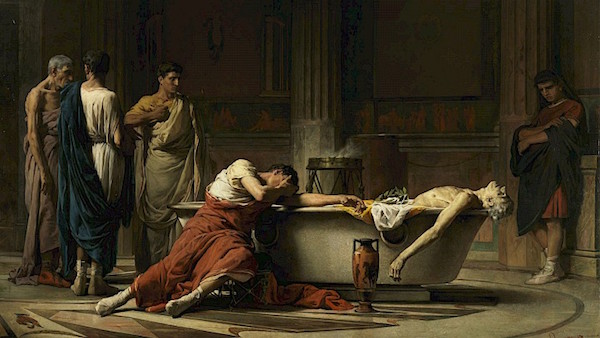

Nero and Seneca, by Eduardo Barrón (1904). Museo del Prado

Seneca had been accused of complicity in the Pisonian conspiracy to assassinate Nero, though he was most likely innocent. According to Tacitus’s account (Annals 15.61), when the news of the Emperor’s orders reached Seneca, he,

nothing daunted, asked for the tablets containing his will. The centurion refusing, he turned to his friends, and called them to witness that “as he was prevented from showing his gratitude for their services, he left them his sole but fairest possession — the image of his life [imago vitae suae]. If they bore it in mind, they would reap the reward of their loyal friendship in the credit accorded to virtuous accomplishments.” At the same time, he recalled them from tears to fortitude, sometimes conversationally, sometimes in sterner, almost coercive tones. “Where,” he asked, “were the maxims of your philosophy? Where that reasoned attitude towards impending evils which they had studied through so many years? For to whom had Nero’s cruelty been unknown? Nor was anything left him, after the killing of his mother and his brother, but to add the murder of his guardian and preceptor.

After these and some similar remarks, Seneca embraced his wife, relieved her sorrows, and asked her not to grieve excessively. But Pompeia Paulina, determined to share her husband’s fate, had already resolved to die by his side.

Woodcut illustration of the suicide of Seneca and the attempted suicide of his wife Pompeia Paulina

They severed the veins on their arms, but Seneca’s aged body, emaciated further by his frugal diet, bled too slowly. He then cut the arteries in his legs and knees, hoping this would give escape to the stiffened blood. With all his attempts unsuccessful, Seneca asked his wife to withdraw into another room, for she was already tormented enough by her wounds to witness the agonizing struggles of her exhausted husband. However, with or without her knowledge, Pompeia was saved on Nero’s orders, and she made no more efforts to take her life.

Seneca, in the meantime, dictated his last discourse to the scribes and asked his close friend to prepare the poison – a method provided in the old days of Athens. When even the poison did not aid his protracted death, Seneca submerged himself in a bath filled with heated water and at last, departed this life. “Whenever his last day comes, the sage will not hesitate to go to his death with a sure step” (De Brevitate Vitae, 11.2) – these are the words he wrote and lived by to the very end.

This episode of Seneca’s life is significant not only by its impressive and memorable acts but also because it is an illustrious manifestation of his philosophical convictions and fundamental values. Judge it for yourself.

Manuel Domínguez Sánchez, The suicide of Seneca (1871), Museo del Prado

Out of the three main philosophers of Roman Stoicism – Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius – Seneca was the only one who wrote in Latin. And, what is more, he could be justifiably regarded as the single most important figure of the Stoic tradition.

Seneca’s works encompass both the foundational principles of early Stoicism and the intense ethical focus of the later Roman Stoicism. However, it would not be a surprise to note that his thought reaches its true zenith when he grapples with the question of how to live. Let us take a closer look.

The central paradigm of Stoic philosophy lies in its view of Nature. Nature, which, for the Stoics, is roughly equivalent to God, is not only organized most rationally and fittingly, but it steers the totality of things to the best and the most harmonious end.

Nature is infused with the divine principle, which is essentially just and rational. Therefore, Seneca often remarks in various ways that the highest good is to live according to Nature. Disregarding the laws of Nature, let alone opposing them, is a blind and vain act only of a mindless man. And that single law of Nature that must never slip out of sight is death.

Seneca by Vorsterman, Lucas. Datierung: 1610 / 1675

Everything that happens originates from necessity and is an inviolable component of the order woven into the chain of causes. Seneca believed that the dread of the imminent end should be surmounted through the practice of “Memento Mori” – consistent meditation on death.

“Death looms all the while, and like it or not, you have to accommodate it” (De Brevitate Vitae, 8.5)

Reflecting on our mortality and anticipating the soul’s release from bodily captivity liberates us from the fear of death. And what other fears could take hold of one who was overcome the dread of death itself?

In his work De Tranquillitate Animi, Seneca illustrates his reasoning with a memorable story: Julius Canus – held in high esteem by Seneca – was condemned to death by Caligula. He was playing chess when the centurion arrived to drag him off to execution. Hearing the order, he nodded to the centurion and said: “You will bear witness that I am one pawn ahead.”

In deep water… a detail from the Death of Seneca by Rubens. Photograph: Gianni Dagli Orti/ Gianni Dagli Orti/Corbis. Source: The Guardian.

With all this in mind, it should come as no surprise that Seneca attempted to relieve a grieving mother who lost her son not by offering traditional consolations, but by prompting her to reflect on the nature of death:

“Let others use soft measures and caresses; I have determined to do battle with your grief; I cannot now influence so strong a grief by polite and mild measures: it must be broken down by force” (De Consolatione ad Marciam, I)

To lose a son is surely a tragedy beyond the grasp of words, but in a world laden with unforeseen catastrophes and premature deaths, is it wise to count ourselves among the safe and invulnerable? Yet we cling onto this shortsighted mindset, “because we never expect that any evil will befall ourselves before it comes, we will not be taught by seeing the misfortunes of others that they are the common inheritance of all men, but imagine that the path which we have begun to tread is free from them and less beset by dangers than that of other people” (De Consolatione ad Marciam, IX).

La morte di Seneca, olio su tela, Musée du Petit-Palais, Parigi

Always expect the worst, Seneca tells us, for if Fortune determines it to be, so it will, and when the misery finally befalls us, it will not catch us heedless and unaware.

“We are deceived and weakened by this delusion, when we suffer what we never foresaw that we possibly could suffer: but by looking forward to the coming of our sorrows we take the sting out of them when they come” (De Consolatione ad Marciam, IX)

We cannot control the necessity-stirred network of events, say the Stoics, since we are bound to come to naught against the reign of Fortune. Yet, we can, and we ought to, become the masters of ourselves.

Our minds are constituted by the same rational principle that governs the universe; therefore, we are rational beings in essence, and with the power of rational judgment – the only power we truly possess – we can take control over our emotional responses and state of mind. In a word, not the course of events, but our relation and approach to these events are up to us to choose.

Portrait of Seneca The Younger. Source: Getty Images.

Once you acknowledge calmly that fate is out of your reach and focus instead on making the best use of what is within your control, you are no longer a desperate pawn but a willful participant of this superior game of Fortune. By understanding the limits of our power, we become free, and by practicing the rational restraints of self-discipline, we become masters of ourselves: “For what can there be above the man who rises above Fortune?” (De Brevitate Vitae, 5.3)

Lucius Annaeus Seneca is not a philosopher one should only read to discover sophisticated answers or to be intellectually stimulated. Among other things, what makes his texts of undying value is the flame of solace and encouragement they ignite. But not a single word of his appeases us or fills our hearts with relief: his solace is bitter; his encouragement warns the worst is yet to come.

If so, how do they still give us strength? They do so because we know, we no longer roam blindfolded. We stand firm, in harmony with ourselves and the universe. Seneca’s words do not soothe – they arm. Picture your greatest fears – he says – picture, and make yourself home with them, so you know that if the ordeal comes, you will survive it. And this is exactly what we need to understand: the worst is endurable if we are ready for it from the beginning. The key is to realize this before it is too late.

One comment

Seneca would have made a good Lutheran.

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.