by Andrew Rattray

What makes a person good? What separates those people who always seem to make the best choices from those who are plagued by their vices? Like so many other philosophies, the Stoics spent significant time and effort establishing their ideas around ethics and virtue to determine what exactly makes a person ‘good’. After all, Stoic practitioners have always sought to live a good life, but how do they quantify that? Well, the Stoics believe that the good life is a virtuous one, and that virtue has four facets, known as the four Stoic virtues.

So, what are the four virtues? Some of you may be familiar with them already, under a different title: the Cardinal Virtues. You see, the Stoics did not entirely devise these virtues themselves. In fact, Plato in the Republic was the first to outline the four virtues, when discussing what characteristics a ‘good city’ would exhibit stating, “Clearly, then, it will be wise, brave, temperate, and just.” These four virtues formed the basis of much ethical discussion amongst many philosophies of the ancient world, and were later absorbed into Christian theology as the Cardinal Virtues. All well and good, but what are the Stoics’ thoughts on these and how do they fit into a life well lived?

Before we delve into that, it is important to consider the idea of the Stoic ‘Sage’, as this will help provide a framework around which we can explain our virtues. You see, in Stoic philosophy the Sage is not a person, but an ideal. A perfect Stoic, and in being so, a perfect person, against whom a Stoic adherent might measure themselves. The Sage is completely free from the impact of the world around them, having achieved the Stoic aim of transcending the circumstances of their life, and reaching a state of total freedom, living in complete accordance with the four virtues.

So, as we know, Stoics strive to live a life in harmony with nature, to avoid excess and temptation, and to accept their circumstances without falling to despair. In order to achieve these things, a practising Stoic must be able to discern the good from the bad. This is why wisdom (or prudence), the first of the four virtues, plays such an important role in Stoic philosophy.

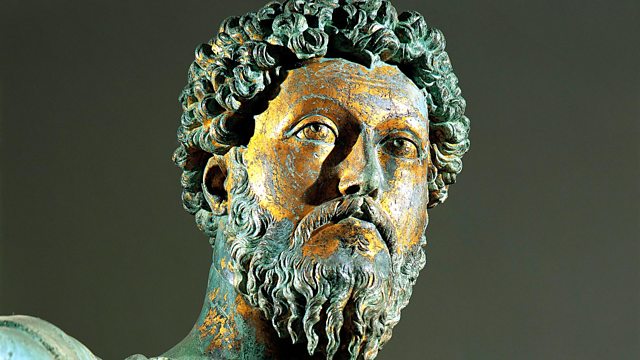

In his Meditations the Roman emperor and dutiful Stoic Marcus Aurelius wrote “If someone is able to show me that what I think or do is not right, I will happily change, for I seek the truth, by which no one was ever truly harmed. It is the person who continues in his self-deception and ignorance who is harmed.” I think this is a prime example of the pursuit of wisdom. We must be open to accepting that we are wrong, and to change our ideas and behaviours when we are confronted with that fact. This is the core of wisdom in my mind: having the ability to change and grow. None of us are born perfectly wise, indeed none of us can ever become perfectly wise, but much like the unattainable ideal of the Sage, it is important that we try. There is virtue in the attempt.

Once we have the wisdom to recognise what we need to change, we must then grasp the next Stoic virtue: courage. In particular, the courage to press forward with those changes. Again, Marcus Aurelius has a fantastic take on this: “Never let the future disturb you. You will meet it, if you have to, with the same weapons of reason which today arm you against the present.” In truth, this is not only one of my favourite insights from Marcus Aurelius, but one of my favourite pieces of wisdom altogether. It is so easy to worry about what the future has in store for us, especially today, with the deluge of negative stories forced upon us through both social media and more traditional outlets. The future does not always look bright, but we must remember that we have faced difficult times in our past, and they too were also uncertain futures once upon a time. No matter what life has thrown at us, we were able to navigate those challenges, thanks to our own fortitude and courage.

The Stoics believe that courage is not in the absence of fear, but in conquering it. Seneca, the Roman statesman and philosopher, writes in one of his letters “There are misfortunes which strike the Sage – without incapacitating him, of course – such as physical pain, infirmity, the loss of friends or children, or the catastrophes of his country when it is devastated by war. I grant that he is sensitive to these things, for we do not impute to him the hardness of a rock or of iron. There is no virtue in putting up with that which one does not feel.” The final line here is vitally important to understanding the Stoic perspective on courage. There is no virtue in acting bravely when one is not having to overcome their emotions to do so. It is in conquering fear and moving forward in the face of adversity, where virtue lies.

After courage comes temperance, or self-management, which yet again forms a key pillar of Stoic practice. Once more, we can turn to Seneca to help illuminate this aspect of Stoic virtue for us. He writes “True happiness is to enjoy the present, without anxious dependence upon the future, not to amuse ourselves with either hopes or fears but to rest satisfied with what we have, which is sufficient, for he that is so wants nothing. The greatest blessings of mankind are within us and within our reach. A wise man is content with his lot, whatever it may be, without wishing for what he has not.” This really speaks to the Stoic idea that in order to be happy we must be free, and that includes freeing ourselves from our materialistic wants and impulses.

Now, that’s not to say that Stoic adherents do not recognise that some things are useful to have: this is the Stoic idea of preferred indifferents. Money is a key example of this. A Stoic will recognise that money is useful, and makes life easier. We should not, however, strive to have it simply because of this fact. If we have some, great, if not, that’s fine too. After all, I’m sure we all know someone who is shackled by their desire for the most up-to-date phone, or designer labels. Again, Seneca brings incising and insightful thoughts on this; “Pleasures, when they go beyond a certain limit, are but punishments.” The Stoics believe exercising our self-management will allow us to free ourselves from the confines of materialism to better focus on living a good life.

The last, but by no means least, of the four virtues is justice, described by Cicero, the Roman statesman and historian as the “…crowning glory of the virtues.” When Stoics speak of justice, it is important to note that this is not just the idea of retribution and balance for wrongs, such as those punishments doled out by the legal system. Stoic justice goes far beyond this and considers what is the moral and correct approach to our dealings with others. This sort of virtue encompasses our attitudes towards each other, our kindness, and consideration to those around us. Marcus Aurelius writes “What is not good for the beehive, cannot be good for the bees.” This beautifully and succinctly captures this idea. When we do not act in accordance with the common good, we are not behaving justly and are damaging not only our community, but ourselves in the process. I like to think of this Stoic sense of justice as acting in a way in which, if everyone acted, things would continue to move smoothly. For example, let’s consider people who pick flowers at the public park. It seems innocuous but were we all to act this way the park would soon be bereft of flowers, and nobody would be able to enjoy them.

Now, despite the separate explanations I have offered here it is important to remember that the four virtues do not stand apart in practice. They are all segments of the same whole. To have one is to have them all. How can we be courageous, just, and temperate without the wisdom to know how, and how could we be wise without the courage to seek the truth, and what use is the truth if we do not exercise it in a way that benefits ourselves and our community? An analogy can help to capture this idea. Consider someone who is multi-talented. Many of today’s celebrities are styled as both an actor, musician, and author, yet they are still one individual. The Stoic virtues work together in the same way.

Defining what’s ‘good’ can be a difficult affair. So often, it’s one of those things that’s nebulous and hard to grasp, but we know it when we see it. However, I think the four virtues go a long way toward setting an objective framework against which we can benchmark such things. What do you think? Do these four virtues go far enough to encapsulate all that one might need to live a good and happy life?

One comment

What is not good for the hive cannot be good for the bees is an interesting thought. In our current economic system, the opposite is often true. For instance, being frugal and saving one’s money is good for the individual, as well as the family, but economists tell us that spending our money, being good little consumers, is good for the economy as a whole. So, if the economists are correct, then what is good for the hive is not, in this case, good for the bees. Similarly, monetary policy that ensures some level of inflation may be good for the economy writ large, but is not good for the little person who tries to live a frugal life.

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.