Written by Bruce J. MacLennan, PhD, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Ancient philosophy was a way of life, a pursuit of wisdom in order to live well. As such, the philosophies of the classical world have much to offer us today. But modern students are confronted with the same dilemma as ancient ones: which should you choose? Epicureanism? Stoicism? Platonism? Instead of picking one, I suggest you view them as stages in philosophical initiation.

Although these ancient philosophies often saw one other as opponents, if we concentrate on their spiritual practices, they form a natural progression, each focused on one of the three parts into which Plato divided the soul. These are (1) the appetites and desires (which we may call the “belly”), (2) the will, feelings, and impulses (the “heart”), and (3) the rational and intuitive mind (the “head”).

This is the perspective I take in my book, The Wisdom of Hypatia: Ancient Spiritual Practices for a More Meaningful Life (Llewellyn, 2013), in which I teach these philosophies as “three degrees of wisdom.” As suggested by the title, the highest degree is the Neoplatonic philosophy of Hypatia.

Epicureanism

In contrast to its modern connotations, the goal of Epicureanism is tranquility, which is achieved by moderating our desires, not by indulging them; it teaches us to understand our needs and desires so we can live a happy life.

Therefore, Epicureans classify human desires as either natural (part of human nature), or non-natural (e.g., power, fame, fortune). Of natural desires, some are necessary (food, shelter, rest), others are unnecessary (gourmet food, friendship). The true Epicurean, then, can be happy because the necessary natural desires are generally easy to satisfy, and the unnecessary ones can be satisfied in moderation.

Moderating desire leads to self-sufficiency, which leads to freedom. Moreover, the Epicureans observed that pleasures are either active — if they require some effort to maintain (which is a sort of pain) — or passive, if they do not. In consequence, the greatest pleasure is an absence of pain, a state of tranquility: the goal of Epicurean philosophy.

The Epicureans also taught that the gods are happy in their heaven and can’t be bothered with mortals, so they don’t harm us. Moreover, when we die we cease to exist, so there is no pain (or pleasure) afterwards. Therefore they taught the Tetrapharmakos or “Fourfold Cure” to our concerns:

“God presents no fear, and death no worry. The good is easy to obtain, but evil easy to endure.”

Of course, these ideas are easy to state and perhaps even to believe, but it takes various spiritual exercises—which the Epicureans taught and which must be practiced— to internalize these attitudes and reactions so that we can actually live this tranquil Epicurean life.

Epicureanism is very valuable for our time as an antidote to consumerism and to some of our pointless striving, but aside from enjoying visits with our Epicurean friends, it does not encourage social engagement. “Live hidden” is a well-known Epicurean maxim.

Stoicism

When we recognize that humans are by nature social and political beings, we need a new philosophy: Stoicism.

Stoicism teaches us the true nature of our freedom and how to live an authentic, socially engaged life. Stoic philosophy has become quite popular in recent years, with a flourishing of books, webinars, and conferences dedicated to the subject. In fact, it is the basis of modern cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Therefore, I don’t need to say too much about it here.

Stoic practice is organized around three interrelated disciplines. The discipline of assent focuses on what is true or not; its goal is to assent to the true, to dissent from the false, and to suspend judgment on the uncertain, which frees us from habitual reactions, for our ultimate freedom lies in our mental assessment of things.

The discipline of desire addresses what is good or not, and teaches that the only truly good thing is moral goodness, the only truly bad thing is moral badness, and all else is fundamentally indifferent. Therefore, the truly good is always obtainable and the truly bad always avoidable, because we can always strive to do what is right (even if we don’t succeed). Whatever the outcome, we must therefore submit to destiny (accept what happens), and then act appropriately the next time.

The discipline of impulse focuses on what we should or should not do, and addresses social obligation, justice, and fate. Regarding social obligation, Stoicism teaches altruism (the recognition that we are made for each other), how to deal with difficult people (who are like us in their basic needs and desires), and true friendship (which should be based on a common commitment to the good).

Regarding justice, Stoicism teaches that we should prefer actions, people, and things that promote the good. Finally, regarding fate, it teaches that a moral choice is successful in itself, even if its intended outcome is not achieved. The sage desires what destiny dictates.

As with Epicureanism, many of these things are easier to say than to do, because in order to enjoy their benefits, we must reprogram our minds and emotional reactions, and that is the point of ancient Stoic spiritual practices and exercises, which are still effective today.

Neoplatonism

Although not technically atheistic, Stoicism is essentially materialistic and doesn’t teach us how to obtain the divine guidance we need to pursue larger personal and social goals. For this we need Platonism (and especially Neoplatonism), which teaches us about the gods, how to contact them, and how to be more like them.

In more modern terms, it helps us understand the archetypal structure of human experience and how to live an authentic human life that respects our inner divinity, or higher self.

Platonism is a continuous spiritual tradition that is at least 2700 years old, with roots in the philosophy of Pythagoras (c.570–c.495 BCE), a spiritual teacher with many of the characteristics of a shaman. It is named, of course, for Plato (427–347 BCE), who established an Academy in Athens (c.387), which continued to function for 400 years.

“Neoplatonism” refers to the further development of this philosophy by Plotinus (204–270 CE) and his successors. It continued to be taught in the Neoplatonic Academy, which was established c.410 CE and survived until Emperor Justinian I banned Pagan schools in 529 CE.

Hypatia of Alexandria (c.350/370–415 CE) was the most famous female philosopher of the ancient world. She was also an accomplished mathematician and astronomer. (You might have seen the excellent 2009 movie Agora about her.) In addition to teaching her private students, she gave public lectures and was an advisor to the governor of Alexandria. Her students and contemporaries called her “the most holy and revered philosopher,” “our divine guide,” and “the blessed lady.” Unfortunately, she was cruelly murdered by a mob stirred up by the Christian bishop Cyril, who called her “that Pagan woman”; other Christians accused her of witchcraft.

Although none of Hypatia’s philosophical writings survive, we can be reasonably confident about her philosophy. Contemporaries said she “taught the philosophy of Plato and Plotinus,” whose writings we have. We also have texts from her immediate Neoplatonic predecessors, Porphyry (c.232–c.305 CE) and Iamblichus (c.204–c.325 CE), and her successors, Hierocles (fl. 430 CE) and Proclus (415–485 CE). We can triangulate among them and make a good educated guess about her teachings.

Central to Platonism is the notion of an objective realm of ideal Forms or Platonic Ideas, each of which is the eternal and perfect principle of some class of objects. The most familiar examples are mathematical objects, such as numbers and geometrical figures, but Platonists were also interested in moral Ideas (e.g., Truth, Beauty, Justice).

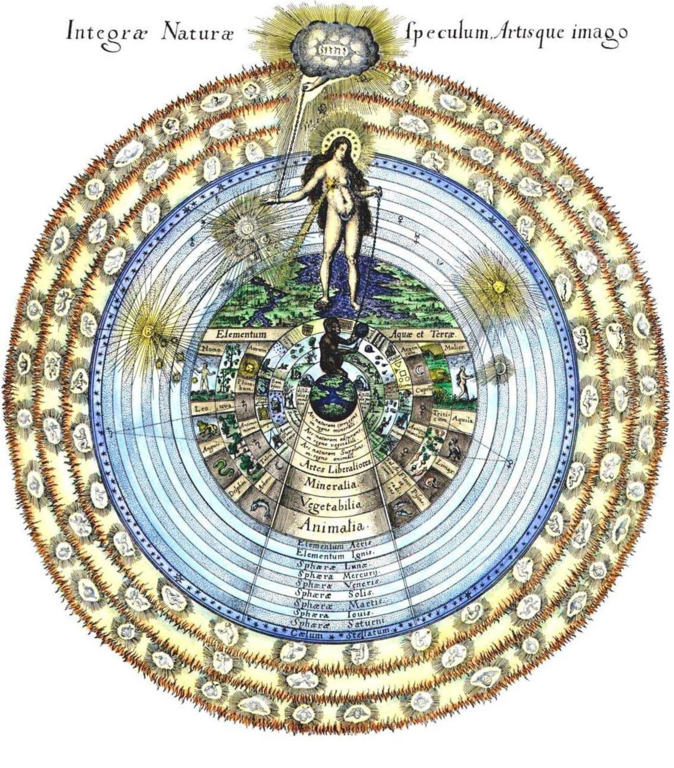

Neoplatonists conceived the Ideas to exist in an eternal and universal “cosmic mind” (Grk. nous), an immutable realm of Being, and they identified the Ideas with the gods who govern our world and our psyches. Above the realm of Being (of duality, of what is and is not) they identified an ultimate principle of unity, which they called the Ineffable One; it transcends all the opposites and is therefore indescribable in words. Below the eternal cosmic mind is the “cosmic soul” (the Anima Mundi), which brings the Ideas into manifestation in space and time in the “cosmic body,” which is ordinary physical reality, the realm of becoming, in which everything is in flux.

Illustration of the cosmos featuring Anima Mundi in the center, “Integra Naturae Speculum Artisque Imago” (“mirror of the whole nature and image of art”), from “Utriusque Cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris metaphysica atque technical Historia,” by Robert Fludd, 1617

All this is the macrocosm, the greater cosmos in which we exist, but each of us is also an image of it, a microcosm. Thus we each have an inner One, an intuitive mind (nous), a soul (including reason and animate life), and a physical body. Your nous grasps intuitively the Ideas in their timeless connections, and your inner One is your highest or true self, the god-image within.

From the perspective of the analytical psychology of Carl G. Jung, the gods are archetypes, the unconscious psychological structures common to all humans, resulting from our evolution; they reside in the collective unconscious (the cosmic nous) and in its image in each of us (your individual nous).

Neoplatonism contains spiritual practices for ascending to the divine realm for guidance, for becoming more godlike, and even for uniting with the Ineffable One (the only way to truly know it). Because the One exhibits beauty, wisdom, and goodness, there are three corresponding ways of ascent to the One: the paths of love, truth, and trust (or faith). Each of these ascends through four levels: awakening, purification, illumination, and perfection (or union).

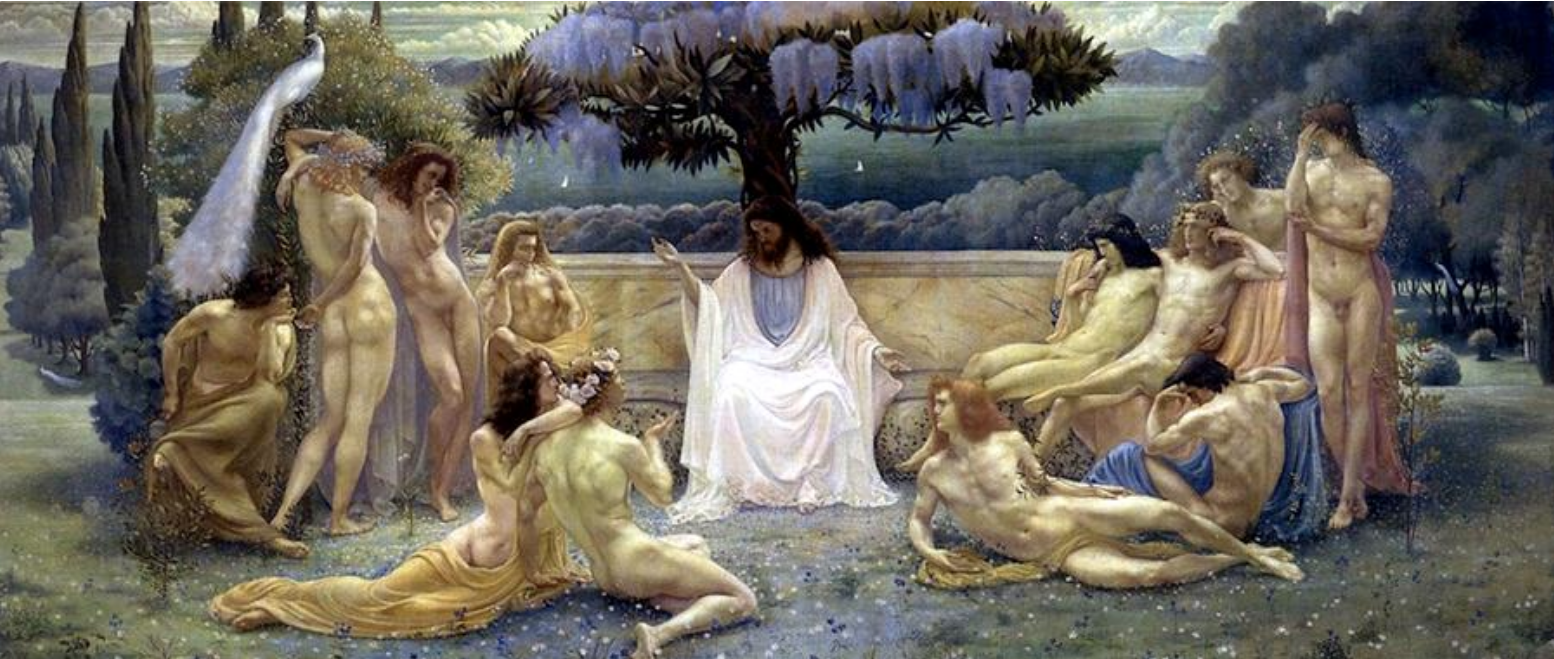

The path of love appears in Plato’s Symposium and ascends through contemplation of beauty in, successively, the body, the soul, the mind, and the One. The path of truth uses meditation on inspired texts (e.g., Homer, Hesiod) and contemplation of nature to grasp the Ideas in the cosmic mind. The path of trust uses theurgy, the use of symbolic rituals for interacting with gods and subordinate spirits for spiritual insight, guidance, inspiration, and assistance. The techniques are closely connected with active imagination, as practiced in Jungian analytical psychology.

Conclusion

Although there is a natural progression from each of these philosophies to the next, we do not abandon the earlier practices when we progress to the more advanced ones; we build on them. Epicurean practices are still useful for Stoics, and Stoic practices are relevant for Neoplatonists. They provide different remedies for different situations. Together they offer an arsenal of spiritual tools to help us live more happily, to deal with life’s troubles, and to achieve our spiritual goals.

Additional Reading:

Addey, Tim. The Unfolding Wings: The Way of Perfection in the Platonic Tradition. Somerset: Prometheus Trust, 2003.

Deakin, Michael A. B. Hypatia of Alexandria: Mathematician and Martyr. Amherst: Prometheus Books, 2007.

Dzielska, Maria. Hypatia of Alexandria. Trans. F. Lyra. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1995.

Hadot, Pierre. Plotinus or the Simplicity of Vision. Trans. M. Chase. Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press, 1998.

Hadot, Pierre. Philosophy as a Way of Life. Ed. & intro. A. I. Davidson. Trans. M. Chase. Blackwell, 1995.

Hadot, Pierre. What is Ancient Philosophy? Trans. M. Chase. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 2002.

Hines, Brian. Return to the One: Plotinus’s Guide to God-Realization. Salem, OR: Adrasteia, 2009.

MacLennan, Bruce J. The Wisdom of Hypatia: Ancient Spiritual Practices for a More Meaningful Life. Llewellyn, 2013. For more on my book, including study guides, please see also https://WisdomOfHypatia.com

Remes, Pauliina. Neoplatonism. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 2008.

Wallis, R. T. Neoplatonism, 2nd ed. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1995.

2 comments

You lost me when you said that we need divine guidance.

For me, these spiritual instruments are very close, with them it is easier to get out of difficult life situations.

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.