By Ben Potter

All that glitters may not be gold, but that hasn’t stopped the shiny yellow stuff from being relentlessly pursued throughout mankind’s civilized existence. Twinkling goodness aside, gold has the virtue of being malleable, ductile, resistant to tarnishing, abundant, easily extracted and, above all else, useless!

Well, perhaps not totally, but it is arguable that the greatest asset gold has above its metallic competitors is that it is, or I should say was, something almost completely nugatory.

Even though now it can be found in computers, mobile phones and is almost the metal of choice for the scientists at NASA, in the ancient world it had few practical applications. The notable exception being, as it is today, in dentistry.

Gold could not help you cook a meal, build fortifications, hunt, fight, or do anything to advance your society. Perhaps because, not despite of this, together with its aesthetic gleaming, gold became the metal of wealth, royalty, power and currency in civilisations the world over.

But where began our fascination with Au (from the Latin aurum, or ‘shining dawn’)?

Well, like with so much else in the annals of man, it appears the Egyptians were the first on the scene regarding the accrual and working of gold, having been in the business of jewellery-making since 5000 BC.

These canny Nile-dwellers also worked out how to accurately grade gold, though that knowledge came several millennia later.

The Sumerians of Mesopotamia also were manipulating the precious metal early on, circa 3000 BC, long before the first ‘Greeks’. It wasn’t until the second millennium BC that the Minoans of Crete developed/perfected a range of refined techniques that saw them produce vast amounts of gold jewellery.

Not that Mediterraneans had a monopoly in this respect; the Chavin culture of Peru was expertly working gold from c.1200 BC.

While it’s hard to pinpoint when gold swam into the ken of the ‘true’ Greeks, it was certainly an important part their literary, mythological and material culture.

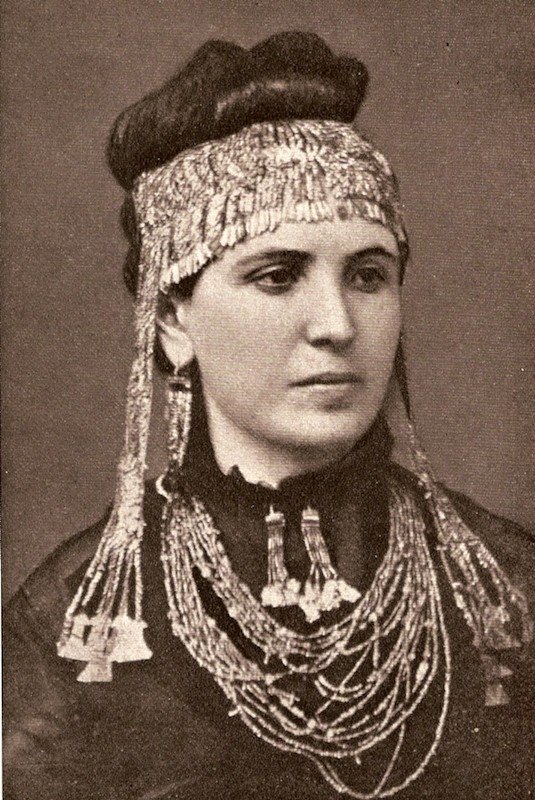

‘Priam’s Treasure’, the haul of gold from the site of the Trojan War (though, contrary to its excavator’s claims, definitely not from that legendary conflict), is a magnificent example of the how gold was worked and revered by the wider Greco world from the third millennium BC.

Within the pages of Homer gold is referred to as something desired by men as a token of wealth (which equated to importance) and as something which naturally reflected the splendour of the immortal gods.

But we need to go further back… Indeed, by the time Homer was penning his epics (c.8th century BC), the blondest and (possibly) most famous of all the Greek myths was already in circulation; Jason and the Golden Fleece.

The Golden Fleece story has become multi-faceted and much analysed with a variety of scholars (both ancient and modern) projecting different interpretations on the tale.

Some say the fleece came from a golden-haired, winged ram, while others prefer the idea that the hide was merely used as a sieve to ‘pan’ for gold.

This is how Strabo referred to the practice in the land of the famous myth, Colchis (modern Georgia):

“gold is carried down by the mountain torrents… the barbarians obtain it by means of perforated troughs and fleecy skins… this is the origin of the myth of the golden fleece”.

At the time of going to press, there are about twenty working theories as to the allegorical significance of the golden fleece story. However, one thing remains clear and constant: gold, even if only metaphorically, has a property of sanctity and deserves our reverence.

It may seem incompatible that gold could be, at the same time, useless, divine, precious and regal… but yet another incongruous spanner was thrown into the paradoxical works when the Lydians of Asia Minor developed gold coinage circa 700 BC.

Though these early coins were of electrum (a naturally occurring gold/silver alloy), it only took 140 years or so for the Lydians to perfect refining techniques that allowed them to produce (and stamp) purely gold currency.

It was a craze that never went away. For the Greeks and Romans alike, gold became something that was not only used to make great and holy artistic works, like the chryselephantine statue of Zeus at Olympia or the statue of Victory in the Roman Curia, but could also be carried around in the pocket of the average soldier or tradesman.

As gold became more than merely something for the rich to wear and the poor to goggle at, the acquisition of it became of primary importance.

Thus by the end of the Classical Age (323 BC) Greek gold mining spanned from the Pillars of Hercules (representing the almost touching tips of Spain and Morocco), across Egypt, and all the way to Asia Minor.

The Romans not only went further afield in their search for these incandescent ingots, but, with their renowned cunning, developed new and improved methods of extracting it (e.g. hushing and sluicing).

Indeed, the Second Punic War (best remembered for Hannibal and his elephants) meant that the abundant gold reserves of the Iberian Peninsula were now under direct Roman rule.

Julius Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul and Britain yielded extra sources of gold. Significantly, Claudius’ attempt to finish what Caesar started in Albion as well as Trajan’s incursions into Dacia were both premeditated on the accretion of the imperial gold reserves.

The imperialistic attitude of the Greeks and Romans towards gold may reflect the fact that relatively little of that commodity naturally occurs in either country.

Despite such an abundance of aurum flooding into Rome, it was still of vital importance that the supply could keep up with the demands of a seemingly exponentially increasing empire.

A result of this was that being buried with large amounts of gold was illegal from 450 BC.

Also, we may be surprised that a proclaimed chrysophilist and narcissist like Nero, though he found plenty of gold leaf for his Domus Aurea (Golden House), had the 103-foot high colossus representing him as the sun-god Sol made of bronze.

Thus, despite his megalomania and profligacy, there were limits even to the emperor’s access to gold.

There were several indirect benefits to our forefathers’ universal benediction of bullion.

Obviously gold gave us pleasant objects to gawp at, but also having a standardized unit of wealth opened up Chinese and Indian trade to the West in a sustainable and organised way.

What is more, the desire to create rather than simply acquire gold was of such importance that the struggle to achieve that impossible feat is from where we derive the term magnum opus.

Though ancient alchemy’s desire of unlocking the secrets of the philosopher’s stone (that would transform base metals into gold and, perhaps, offer eternal life) proved fruitless, it did lay the foundations upon which all subsequent chemistry was built.

Without this motivating force, it is conceivable modern science could have been held back by centuries.

And, of course, though it had to wait a couple of thousand years, gold has now become a prominent metal in computing, aerospace, healthcare and even glassmaking; all happy offshoots of the metal being so ubiquitous in every society.

Though, for classics enthusiasts, it must be acknowledged that gold, or specifically the lack of it, was at the heart of the demise of the Roman Empire.

Emperor after emperor found that swelling the coffers with what the Incas described as ‘the tears of the sun’ in an increasingly chaotic, bloated and unruly empire was beyond the scope of practical politics.

And if an emperor could have been pardoned for grumbling at the thought that reserves of gold were at the heart of merely maintaining the status quo in his faltering realm, he could have been forgiven for failing to enjoy the irony… Rome’s material opulence was a key motivating source behind the sackings of that city in 410 AD and 455 AD (by the Visigoths and Vandals respectively) which brought about her final, whimpering demise in the west and plunged Europe into what later became known as the Dark Ages.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.