(The Dying Gaul, or the Dying Galatian, an ancient Roman depiction of a defeated Celtic warrior)

After victory in 45 B.C., Caesar was crowned Dictator Perpetuo and thus the 500-year reign of the Roman Republic imploded, due to the insidious cancers of autocracy and the cult of personality.

In the wider scope of Roman history, Caesar’s political victory was the result of his military accomplishments, especially his success in Gaul. Among his men, Caesar commanded complete authority and trust, and because of this, Caesar’s Commentarii de Bello Gallico – his third-person account of the wars – is replete with examples of Roman courage and prowess in battle.

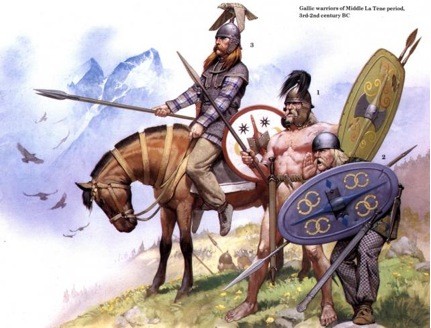

(Modern interpretation of ancient Gallic warriors)

In Gaul, not only every tribe, canton, and subdivision of a canton, but almost every family, is divided into rival factions. At the head of these factions are men who are regarded by their followers as having particularly great prestige, and these have the final say on all questions that come up for judgement and in all discussions of policy.

Unlike the Germans and the Belgic tribes who were ruled by kings, the Gallic tribes were predominantly ruled by oligarchies composed of warrior noblemen, who are called “knights” in most English translations of Caesar’s text. These Gallic knights acted as magistrates, military leaders as well as serf-holding landowners. In this, they eerily presaged the later feudal system of the medieval period – a system that saw its greatest heights in France, no less.

According to Caesar, the development of the Gallic oligarchies was brought about in order that “all the common people should have protection against the strong.”

Caesar, who came from a family with a history of supporting people’s assemblies and other populist causes, more than likely found this praiseworthy. Throughout his notes he is keen on showing how the Gauls, who had by this time become acquainted with Roman and Mediterranean customs due to trade, differ from the more “uncivilized” Germans.

The Druids officiate the worship of the gods, regulate public and private sacrifices, and give rulings on all religious questions. Large numbers of young men flock to them for instruction, and they are held in great honour by the people. They act as judges in practically all disputes, whether between tribes or between individuals; when any crime is committed, or a murder takes place, or a dispute arises about an inheritance or a boundary, it is they who adjudicate the matter and appoint the compensation to be paid and received by the parties concerned.

(A 19th-century engraving of two Druids)

As a nation the Gauls are extremely superstitious; and so persons suffering from serious diseases, as well as those who are exposed to the perils of battle, offer, or vow to offer, human sacrifices, for the performance of which they employ Druids. They believe that the only way of saving a man’s life is to propitiate the god’s wrath by rendering another life in its place, and they have regular state sacrifices of the same kind. Some tribes have colossal images made of wickerwork, the limbs of which they fill with living men; they are then set on fire, and the victims burnt to death (emphasis mine).

This horrendous image of a colossal wicker man filled with living humans bound for a fiery death is arguably the most culturally important image in The Conquest of Gaul. Specifically, Caesar’s brief description of a certain type of human sacrifice practiced by the Gallic tribes inspired not only a 1967 British horror novel by David Pinner, but also a whole genre of cinematic horror – Mark Gatiss’ “folk horror.”

This mixture of fact and fiction is at the core of Caesar’s account and since few popular representations of Gallic and/or Celtic paganism can escape Caesar’s text, it still remains that The Conquest of Gaul is the seminal, yet biased authority on all matters Celtic. So perhaps in spite of Caesar’s best propaganda efforts, he still left an important historical reference.

One comment

Wasn’t this book a primer on the genocide of the Gauls

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.