Written by David Hooker, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The Tragic Road to Tyranny

Imagine your leader is a brilliant and bold military genius who, through multiple conquests, has expanded the borders of your country by orders of magnitude. He does it because he and some of your leaders have ambitions of empire, need of new wealth, and access to more slaves (to keep building the domestic economy and staffing the army). His campaigns are tremendously successful as a result of a crack military.

Your leader also gets his way at home, manipulates the politicians, is a serial adulterer who sleeps with some of the wives of prominent men of your country, and is generally feared. Having shared power earlier in his career with two other leaders (as a “Triumvirate”), his military successes as Imperator (supreme military commander) fuel his ambition to consolidate his power and rule the country by himself.

With the Triumvirate no more (one has died, the other was defeated by your dear leader in battle and subsequently killed in another country), he is free to assert his will to power and assume sole possession of rulership. He initiates several domestic “works” programs – land reforms, calendar reform, support for his military veterans, and construction projects, which increase his popularity with the public. They now revere him as the classic, beneficent “strong man” leader.

All of this angers many of the elites of his country, since it has heretofore enjoyed a republican form of government for quite some time. After unconstitutionally declaring himself “dictator for life” (dictator perpetuo), he is finally murdered by stabbing (23 times!) in a conspiratorial plot by several influential senators. One may even have been his illegitimate son by one of his several lovers.

Of course, I’m speaking of Gaius Julius Caesar, who was killed on the 15th of March, 44 B.C. (“Beware the Ides of March”!). Several episodes of political intrigue and civil war ensued over the next thirteen years and the glory days of Roman constitutional government were never restored.

Octavian, the adopted heir of Julius, eventually defeated Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. In 27 BC, after vanquishing his remaining rivals to power, Octavian is granted the title of “Augustus” (“the Venerable”).

Though pretending to “restore” the Republic, Augustus himself retained all real power as the Princeps (“first citizen”) of Rome. He had eventually become the autocrat that Julius had aspired to be. He was ruling over an Empire now.

I support the left, though I’m leaning to the right,

I support the left, though I’m leanin’ leanin’ to the right, yeah

But I’m just not there when, when it’s coming to a fight.

“Politician” – Eric Clapton & Cream

Let’s face it: the business of politics can be nasty in the extreme, and some politicians are highly skilled in being greedy, equivocating, disingenuous scumbags (as alluded to in the lyrics above from the classic Cream song).

Many countries have experienced the assassination of a significant leader at a critical historical time, such as Julius Caesar in ancient Rome. Think Abraham Lincoln in America (the actor John Wilkes Booth cried sic semper tyrannis – “thus ever to tyrants” – after doing the dirty deed), John F. Kennedy, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary (precipitating the First World War), Mahatma Gandhi and Indira Gandhi of India, Anwar Sadat of Egypt, and Yitzhak Rabin of Israel, to name a few in just the last two centuries.

All of these leaders had significant popularity and followings, but there was just enough bitter dissent that bad actors hastened their demise in evil fashion. Just as in the case of Julius Caesar, these assassinations often precipitated times of social and cultural upheaval following the event.

Politics in America

As I write this, we’ve just begun the nomination process for Democratic candidates for President in 2020 here in the USA, and the name-calling and mudslinging have begun in earnest. This promises to be a very bitter, partisan, and divisive year in the US politically, as half the electorate supports the Populist incumbent Donald Trump, and the other half of the electorate will support whichever candidate emerges from the Democratic Convention in July.

There are many in America who wish there would be a viable alternative to the two major political parties (such as the Libertarian party), both of which have abandoned their traditional mandates and principles, for the most part, in order to pander for votes. The labels “Republican” and “Democrat” have little meaning today.

Donald Trump, hugely popular in his base, is a billionaire real estate developer and television show entertainer who basically usurped the Republic party and moniker through his very popular debate performances back in 2015 and 2016, against a very deep team of professional “Republican” political candidates.

I refer to him as a Populist because, according to his rhetoric, that is what he actually is. This year promises to be highly entertaining for people watching the Democrat side, as we see several people coming from all different political and financial angles jockeying for their party’s nomination. (“Let’s get ready to rumble!” as big time boxing announcer Michael Buffer would say.)

Many people would rather avoid the topic of politics, with its inherent divisiveness and messiness, but I’m afraid we need to take a more practical view. Whether we like it or not, we are part of a larger political community, and we all need to (somehow) live together in relative peace and order, and we all need political representatives to take care of the business of our various nations.

The Political Animal

We are indeed a “political animal” (to use Aristotle’s phrase), whether we care to be or not. What kinds of government are the best? What kinds of leaders are the best and most efficacious at governing and taking care of the people’s business? Should power be autocratic or shared? Furthermore, are these leaders and political representatives ruling truly for their people, or are they just interested in serving themselves and lining their own pockets?!

These are questions human beings have struggled with for millennia, ever since we stepped out of Africa in small groups of hunter-gatherers. Even small groups need a leader of some sort, a decision maker of last resort – one with experience and wisdom to enhance the outcome of the struggles of the group.

Eventually, humans migrated all over the planet, discovered agriculture, domesticated animals, bred like rabbits, and settled down with larger groups of other humans in villages and eventually cities (hence, the polis) to live. The growth of survival skills and entrepreneurship enabled the division of labor (specialization of trades and professions), which allowed the city to work more efficiently.

Large groups of humans need ever larger and more knowledgeable groups of leaders, so it was inevitable that more complex forms of government (some with written charters, or laws) evolved, involving larger groups of local “politicians” – magistrates, judges, priests, and some kind of supreme leader (a king, or tribal chieftain, or religious figure) to head up the organization and lead the city. The city-state was born.

The Forms of Government

What does Classical Wisdom have to say on the evolution of government? Our wise readers know the answer: a lot.

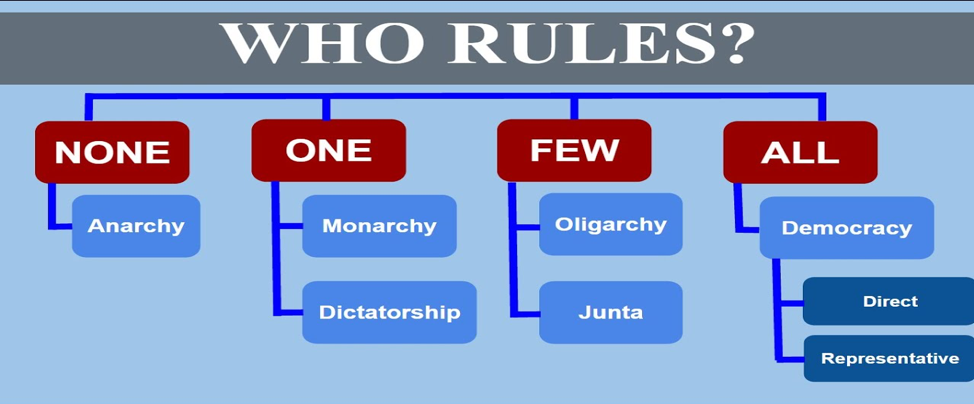

As you might imagine, over centuries, governments have oscillated back and forth from various types of despots and autocrats, such as kings, dictators, and tyrants, and on to the other extreme of pure Democracy (as sometimes in ancient Greece), where all the citizens of a polis (or city-state, like Athens) traded places in the work of governing and tending to the people’s business.

Sometimes the various cities in Greece were ruled by oligarchs (rule by the few), plutocrats (rule by the very wealthy), military generals (“strong men”), and enlightened Democrats (think Pericles in Athens) coordinating policy with other representatives of the people.

The Greek historian Polybius (ca. 208-125 BC) wrote a terrific book entitled “The Histories,” which covers the period from 264-146 BC. This work is especially enlightening for us moderns, as we tend to think that our governments must be more evolved and enlightened than any from the distant past.

A more accurate description of political history is one characterized by an ongoing oscillation back and forth between autocracies and republicanism (with written constitutions guaranteeing certain rights to all, with at least some elected representatives and an elected Executive, or President). And all points in between.

Many ancient kingdoms and nations had a supreme religious leader and government was looked upon as the means by which their divine mandates and holy scriptures were adhered to (a theocracy). There was no “separation of church and state.” This idea is still very much alive and well today.

The modern tripartite form of government (with executive, legislative, and judicial branches) may be said to draw a great deal from the writings of Polybius. (With assistance from Baron de Montesquieu and John Locke, both of whom wrote extensively on the separation of power via checks and balances in the tripartite system, as argued for in the Federalist Papers in the case of the newly-born American Republic.)

In parsing the various forms of government popular in Polybius’ days – kingship (monarchy), aristocracy (government by “the best”, or the highly accomplished and well-placed), and democracy, he explains that the “best constitution is that which partakes of all these three elements.” As he wrote,

“And this is no mere assertion, but has been proved by the example of Lycurgus, who was the first to construct a constitution – that of Sparta – on this principle. Nor can we admit that these are the only forms: for we have had before now examples of absolute and tyrannical forms of government, which, while differing as widely as possible from kingship, yet appear to have some points of resemblance to it; on which account all absolute rulers falsely assume and use, as far as they can, the title of king. Again there have been many instances of oligarchical governments having in appearance some analogies to aristocracies, which are, if I may say so, as different from them as it is possible to be. The same also holds good about democracy.” – Polybius, TheHistories

Polybius goes on the explain that these three forms of government can all, under the right cirumstances socially, deteriorate into three associated forms; namely, “despotism” (tyranny), “oligarchy” (rule by the few), and “mob rule” (perverted democracy, where non-virtuous citizens use the power of government to illegally allocate resources to themselves and selfishly pervert justice – the “tyranny of the majority”).

No One-Size-Fits-All

It’s often surprising for moderns to read of severe criticism of democracy coming from ancient Greeks such as Aristotle and Polybius, but they knew by first hand experience how direct democracies could get out of hand.

Of course, Greece had experience with democracy in small city-states where direct participatory democracy could be practiced by all citizens. What we have today (in the USA, for instance) is a democratic republic, whereby eligible citizens who have registered to vote participate in elections that elect representatives from their various districts (for the House of Representatives) and states (Senators), and a President.

Republics (from the Latin res publica – “public thing”) have written constitutions, which have naturally evolved over the centuries. This form of government is very well suited to western countries comprising large geographic areas.

Personally, I believe that government should be malleable. In other words, there isn’t one form of government entirely suitable to all countries. Democracy (specifically republicanism) is suited better for western countries who have evolved from the Greco-Roman civilization. Other countries, depending on their religious make-up, the temperament of their people, and the histories of their countries and peoples might be more amenable to another sort.

I know many in the west think that “democracy” (sometime ill-defined) is the “be all” and “end all” of governmental forms and should be foisted on all the other countries of the world, whether they like it or not! I beg to differ. Many of the wars in my lifetime have been waged with this premise, and it has often led to disaster; enormously wasteful of human life and taxpayer (usually American) money.

The Vietnam conflict is a case in point, from the involvement of the French in the 1940s and 1950s on up to the involvement of the USA in the early 1960s up until 1975 . Having visited that wonderful country many times in my travels, I can guarantee to anyone that the Vietnamese people, very resourceful and hard-working, all want a better life for themselves and their families. They want better jobs, more money, more “good life,” just as most people of the world do.

Capitalism has won out there (especially in the South), as Vietnam is today a highly productive and prospering place, as I figured it would be. It’s up to government to follow along and do what’s best for their people. Perhaps democratic republicanism will win out there over time, as well. Only time will tell.

Lessons from Game of Thrones

George R.R. Martin’s fantastic series “Game of Thrones” wrapped up last year, and I will miss it terribly. I loved the series, all its characters (with superb actors and chemistry among the cast), the story lines, the music, etc.

Like thousands of other men all over this planet, I’m sure, I fell in love with the young, beautiful, platinum blonde Queen Daenarys Targaryen (played so well by the British actress Emilia Clarke). I really enjoyed watching her story line unfold throughout the series, having no idea how the show would end. Being a romantic, I was always hoping for a “happily ever after” ending between her and her paramour and defender, Jon Snow, of Winterfell (the North Country).

The ending of the final episode was massively disappointing to me. Not at all because of the actors, or technical production, etc. all of which were at the highest level throughout the show’s run. The story line took a twist that I only slowly caught on to, and it is very germane to my article here on politics.

Having been on a series-long quest to reunite the land of Westeros and eventually reclaim Targeryan dominion over the Iron Throne, Queen Dany slowly builds allies and a formidable army along the way to reach her goal. She also manifests very clever political skill during her journey.

In the final episode, the series comes to its denouement with the expected final battle between the über-females of the series, Queen Dany and her final nemesis, evil Queen Cersei Lannister, who holds the Iron Throne at King’s Landing. Extremely angered by the killing of one of her beloved dragons, which begins the final battle (and the murder of her close friend and female attendant at the command of Cersei), Queen Dany, totally consumed by a thirst for vengeance, goes on an absolutely murderous rampage!

It isn’t pretty… Riding atop her one remaining dragon, Queen Daenerys unleashes an incredibly brutal wave of death onto the inhabitants of King’s Landing, with no discrimination between innocent women and children and the actual soldiers still waging battle for Queen Cersei. With the aid of Jon Snow’s Northmen, and the “Unsullied” (her army of liberated slaves), Queen Dany prevails.

But the aftermath is astonishing: death and destruction lies all over, with few of the inhabitants of King’s Landing left alive. Her nemesis Queen Cersei dies a terrible death while trying to escape the castle, as she is crushed by the collapsing building.

Following the carnage, Queen Dany gives a chilling speech to her victorious army, laced with fascistic, triumphal overtones of her autocratic (tyrannical?) rule to come over all of Westeros, “freeing” all peoples remaining under other leadership (whether they want it or not).

War, bitterness, and personal vengeance have changed her soul dramatically. (Was she this way all along?) She has succumbed to the allure of power – “absolute power corrupts absolutely,” said the British 19th Century Lord Acton so aptly. Queen Dany was, sadly, so corrupted.

Jon Snow, with the battle being long over (those still alive had long been ready to surrender), is incredulous (as I was) that his beautiful Queen Daenerys remained airborne on her dragon raining death indiscriminately on all who remained alive. Overkill, indeed.

Finally, the carnage ends, and after listening to Dany’s chilling speech, Jon meets the Queen in the Iron Throne room. Sadly, after a tender moment he puts a knife into her and she dies in a pool of her own blood.

I have to say he did the right thing, especially since Jon knows that Dany would’ve eventually killed his sister, Sansa Stark (Queen in the North), for not submitting to her rule. A tragic end to a great series. And so politics – and the endless quest for ultimate power – sometimes goes…

Of, By, and For the People

Politics is full of tragedy, yet also has been the vehicle of great human progress and advancement. Governments, properly instituted, can empower the creativity, ingenuity, and drive of their people, all of whom just want better lives and various degrees of freedom.

“That government governs best which governs least,” said the Classicist President Thomas Jefferson. I believe he was quite correct. We definitely do need laws and government enough to enforce those laws and protect the people and their rights, and checks and balances in our governmental systems to ensure that no murderous autocrat, corrupted by lust for power, does something either amazingly stupid or evil (Hitler, for example).

And, as Aristotle reminds us in his Nichomachean Ethics, a people of sufficient virtue is needed to keep the system running optimally. The American Founding Fathers knew this. They are like demigods to me when compared to what we have now!

As the Constitutional Convention of 1787 was wrapping up in Colonial America, Benjamin Franklin was asked what kind of government the newly-independent America would have. He replied: “A Republic – IF you can keep it.”

Benjamin Franklin c. 1785 by Joseph Siffred Duplessis (1725-1802). (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Franklin knew very well that a people of virtue were required to make this form of government work. A people who were moral, educated, civic-minded, hard working, and involved in government as a free people.

I would remind anyone, wherever they happen to live, to get involved in your governmental process however you can contribute. Any freedoms you now enjoy can easily be taken away if people are too lazy, indifferent, and apathetic to get involved in the process. By all means, should you enjoy the privilege of voting, VOTE! Let your voice be heard, no matter how “small” it seems. Ultimately, it does make a difference.

As our friend Plato said, all those centuries ago: “The punishment which the wise suffer who refuse to take part in the government is to live under the government of worse men.”

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.