Written by Van Bryan, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

At the opening of the Crito, a dialogue by the philosopher Plato, Socrates has been imprisoned. He is awaiting his execution for the supposed crimes of corrupting the youth and believing in strange gods. However, it is only by chance that Socrates is still alive, trapped in his cell. Around the time of his trial, the Athenians had sent a small galley on a religious mission to the Aegean island of Delos. It was believed that the island was sacred to the God Apollo and so while the ship was away, no executions would take place.

Socrates’ wealthy friend Crito visits with the philosopher in the early hours of the morning. He informs Socrates that the ship from Delos will be arriving soon and that he will undoubtedly be killed once it lands at Athens. There is little time left, Crito assures Socrates that he would be able to bribe the prison guards and allow Socrates to escape from Athens. The philosopher would avoid his execution, and live out his days in Thessaly. And then something very strange happens: Socrates refuses…

Instead, Socrates launches into a series of questions (as he tends to do) and engages in a philosophical discourse with his worried friend, Crito. Socrates first asks if we should concern ourselves with the opinion of the majority, they may harm a man’s flesh, but can they ever damage his soul? Socrates does not believe so; he then asks if it is justified to harm others who have caused us harm. Crito considers this and then concludes that wrongdoing, by nature, is never justified and that we must never do wrong to others even when we suffer under injustice. Socrates consents to this point and acknowledges that many would not agree with him on this matter. He even states…

One must never, when wronged, inflict wrong in return, as the majority believe, since one must never do wrong.– Plato, Crito

Socrates reaching for the hemlock.

Socrates then embarks on another line of thinking that closely mirrors The Social Contract Theory which would be refined by Thomas Hobbes some two thousand years later. Socrates considers escaping from prison to be an indictment of the entire Athenian society. It would undermine the authority of the Athenian courts and the fledgling democratic government.

After all, Socrates gave no complaint when Athens sheltered him, educated him, attended to his family, and protected him from invaders. Why should Socrates now attempt to destroy Athens simply because the city has brought unfavorable circumstances upon him? As the philosopher puts it, we may either leave a society, attempt to persuade it to change or accept whatever punishment it inflicts upon us. There are no other options for a person of integrity.

You may disagree with the philosopher on this point. Surely if we were awaiting execution we might rightly consider escape, the laws be damned! However, Socrates has just pointed out previously that one must never harm, even when harm is brought upon us. The only real harm that can be brought on a person is that which harms the soul.

The Death of Socrates, Jacques-Louis David, 1787. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Socrates, a man who sought to persuade Athens to seek wisdom, would rattle the cages of those in power, embarrassing them in the process. He would inevitably attract the disdain of many prominent men. He would attempt to persuade them to change, to accept wisdom rather than ignorance. He would be punished. And while suffocating under the weight of cruelty, he would gracefully accept his punishment, throwing into stark contrast the injustice of society.

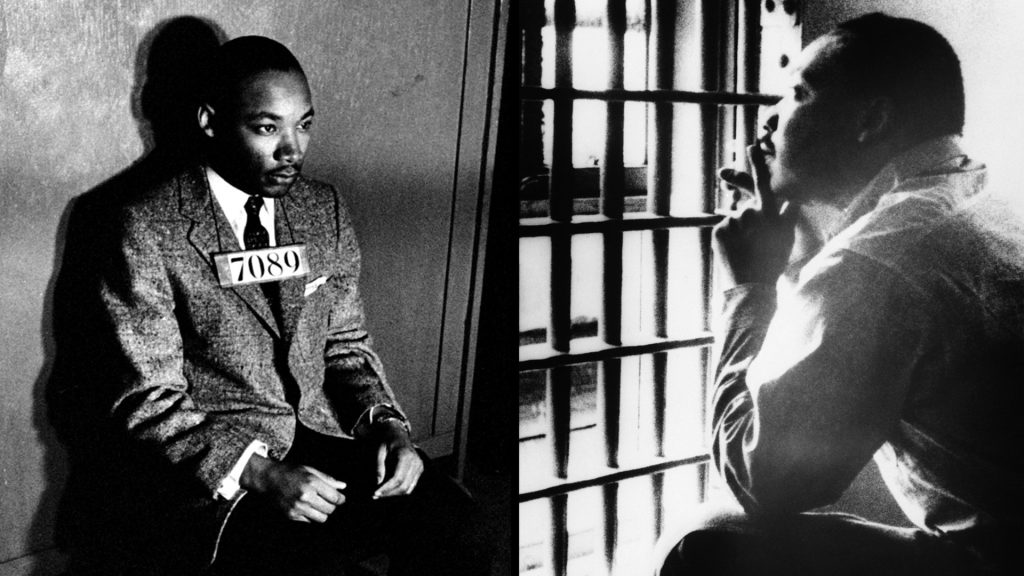

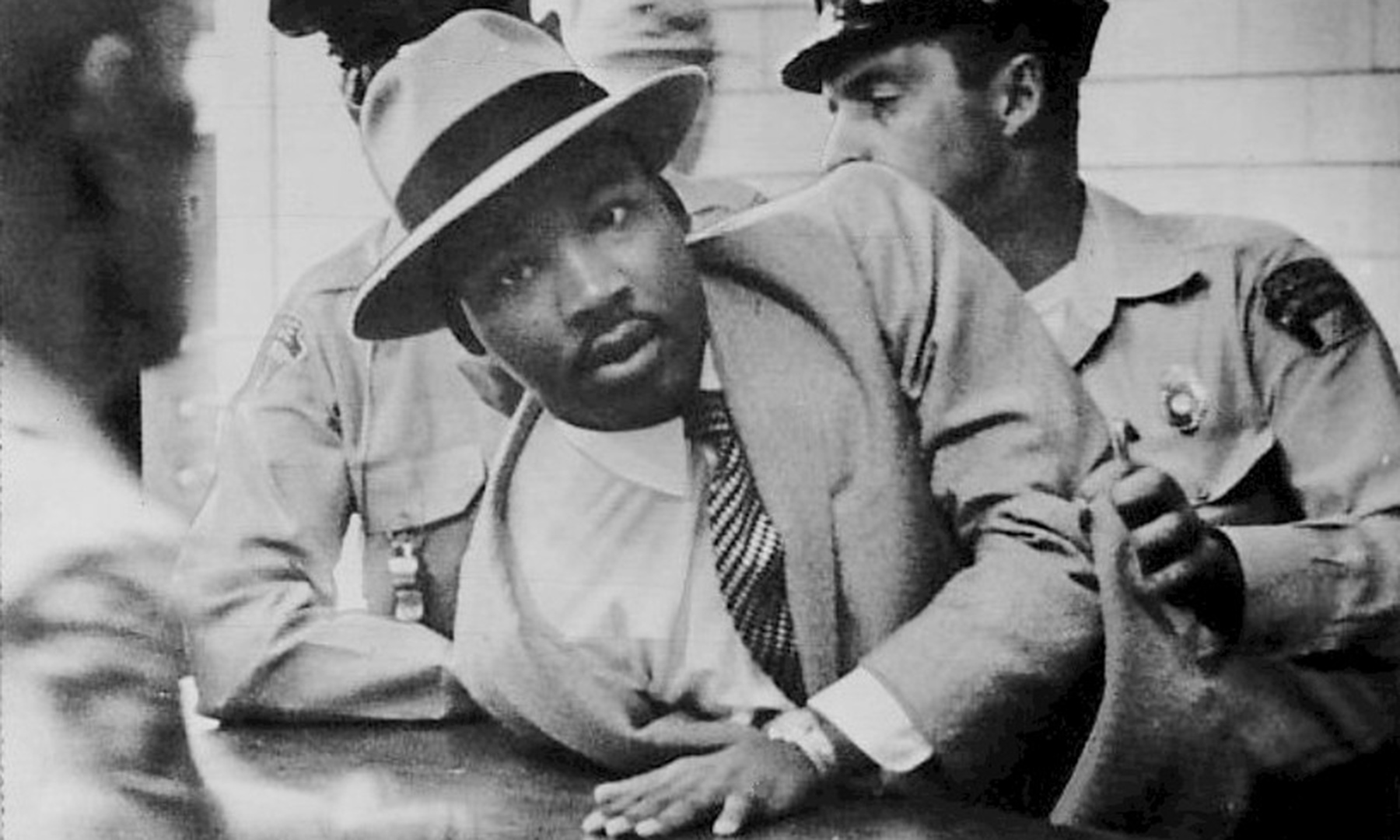

Some two thousand years after Socrates had had this conversation with Crito, Martin Luther King Jr. found himself sitting in a jail cell as well. It was on April 12th, 1963 that King was arrested in Birmingham, Alabama in response to a coordinated series of sit-ins and nonviolent demonstrations. During his time in jail, King wrote an open letter that addressed the need for nonviolent resistance, civil disobedience, and the perils of racial inequality in America.

The Letter From Birmingham Jail would become a centerpiece for the American civil rights movement and a concise proponent for the act of civil disobedience. In the face of racial inequality and injustice, the letter outlines how the use of nonviolent protest must be implemented to bring about lasting and fundamental change. King outlines that active, professed refusal to obey unjust laws is not only necessary for social activists, but should be morally obligatory for any individual who believes in true justice and human dignity.

MLK in Jail. Don Cravens / The Life Images Collection / Getty; Bettmann / Getty. Source: The Atlantic.

King compares the laws of the American South to the laws of Nazi Germany, where it was “illegal” to aid a Jewish man or woman. And yet, King confides that if he had been in Germany at that time, he would have undoubtedly done so. Refusing to obey laws that, as King puts it, degrade the human personality is the noblest of tasks for anybody looking to seek fundamental change in an unjust society.

A key to civil disobedience (as Socrates and King would demonstrate) is that once we refuse to obey unjust laws, we must graciously accept the punishment, regardless of what is fair. Socrates accepted his execution without quarrel. King spent time in a jail cell for holding a peaceful demonstration. This is the key to civil disobedience and social activism. By suffering under the weight of unjust punishments, we demonstrate the unfairness of society; in this way, we force others to reconsider the true nature of justice.

King and Socrates appear to be bound by their struggle for progress. King even mentions the great philosopher in his letter when he writes…

Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, so must we see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood.– Martin Luther King, Letter From Birmingham Jail

30th March 1965: American civil rights campaigner Martin Luther King (1929 – 1968) and his wife Coretta Scott King lead a black voting rights march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital in Montgomery. (Photo by William Lovelace/Express/Getty Images). Source: WGBH NEWS

If these two men were indeed engaged in a similar struggle to break free from the chains of oppression, then it is perhaps not surprising that they would bother to suffer tragic endings for the sake of their ideals. Socrates would be put to death by the very state he wished to enlighten; Martin Luther King would be assassinated on April 4th, 1968 while standing on the second-floor balcony of his hotel in Memphis, Tennessee. He had been shot by James Earl Ray, a man who was renting a room at a boarding house across the street from King’s hotel. It is interesting to note that Robert Kennedy, immediately following the assassination, gave a speech where he quoted the great Greek playwright Aeschylus.

He who learns must sufferAnd even in our sleep pain that cannot forgetFalls drop by drop upon the heart,And in our own despite, against our will,Comes wisdom to us by the awful grace of God.– Aeschylus, as quoted by Robert Kennedy

Socrates and King would be remembered posthumously with admiration and respect. Their ideas would attract the hatred of many, and they would suffer unjustly for their pursuits. And tragically they would both die for their ideas, struggling to improve this world as best they could.

Separated by thousands of years of history, these two men struggled valiantly for justice in a society that sought to destroy them. United by purpose, Socrates and King remain a reminder to us all that change comes slowly and often painfully. And whatever enlightenment we enjoy, it is often thanks to great individuals throughout history who suffered on our behalf, to ensure that true justice is found.

3 comments

One can only say the following: some people must lose a lot in order to affect changes that are moving society towards a more ‘normal’ condition — and yet there are many more changes that have to be made before society will be normal…

Society is so irrational at this moment that one must still put mythology above modern science in some religious (usually protestant or something similar) communities. This is actually intellectual oppression. Philosophy is also as difficult to find as one would chicken teeth in [such] communuties.

It’s a pity that people like Socrates and King had to suffer as much as they did just to obtain some normality in a sea of irrationality…

That means that there will be many more [such] martyrs before society will resemble something that will look ‘normal’; what a pity…?

In today’s society it is better for someone to be insane without crazy beliefs than to be rational and somewhat normal…

PJ

Your comment is awaiting approval.

One can only say the following: some people must lose a lot in order to affect changes that are moving society towards a more ‘normal’ condition — and yet there are many more changes that have to be made before society will be normal…

Society is so irrational at this moment that one must still put mythology above modern science in some religious (usually protestant or something similar) communities. This is actually intellectual oppression. Philosophy is also as difficult to find as one would chicken teeth in [such] communuties.

It’s a pity that people like Socrates and King had to suffer as much as they did just to obtain some normality in a sea of irrationality…

That means that there will be many more [such] martyrs before society will resemble something that will look ‘normal’; what a pity…?

In today’s society it is better for someone to be insane with crazy beliefs than to be rational and somewhat normal…

PJ

Your comment is awaiting approval.

Your comment is awaiting approval.

One can only say the following: some people must lose a lot in order to affect changes that are moving society towards a more ‘normal’ condition — and yet there are many more changes that have to be made before society will be normal…

Society is so irrational at this moment that one must still put mythology above modern science in some religious (usually protestant or something similar) communities.

This is actually intellectual oppression, as well as the oppression of children.

Philosophy is also as difficult to find as one would find chicken teeth in [such] communuties.

It’s a pity that people like Socrates and King had to suffer as much as they did just to obtain some normality in a sea of irrationality…

That means that there will be many more [such] martyrs before society will resemble something that will look ‘normal’; what a pity…?

In today’s society it is better for someone to be insane with crazy beliefs than to be rational and somewhat normal…

PJ

This is the ‘edited version’ of the previous two statements…

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.