By Benjamin Welton, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The great British novelist, poet, and World War I veteran Robert Graves created one of the most agonizing scenes in fiction when, in his 1934 novel I, Claudius, he portrays a grieving Emperor Augustus crying to the ghost of his general Publius Quinctilius Varus:

“Varus, Varus / Give me my three Eagles back! / Lord Augustus tore his bedclothes, / Blankets , sheet and counterpane. / “Varus, Varus, General Varus, / Give my Regiments back again!”

In the ballad that Emperor Claudius recalls so well, Augustus mourns the loss of the Nineteenth, Twenty-Fifth, and Twenty-Sixth Regiments and their battle standards. These fine soldiers, who were some of the best representatives of Rome’s martial spirit and ironclad discipline, were the victims of an incredibly successful German ambush that occurred in A.D. 9. The leader of the German tribesmen, Arminius, became a hero, while the Roman war machine became suddenly vulnerable.

Finally, after years of unchecked conquest, the mighty Roman Empire met an enemy (the ancient Germanic tribesman) and a field of battle (the Teutoburg Forest) that it could not vanquish without great loss.

Over a thousand years later, the German victory at Teutoburg Forest was resurrected as a rallying cry for German nationalists during the age when the fragmented German states were under threat from a new foreign emperor. Instead of Augustus and his legions, the new Pan-German warriors invoked Teutoburg Forest in order to battle Napoleon and his Grande Armée.

The Hermann Monument in the Teutoburg Forest

The seeds of the battle began well before the creation of the Roman Empire. During his conquest of nearby Gaul, which was inhabited by warlike Celts, Julius Caesar undertook an ethnographic study that doubled as a political justification of his personal military adventures entitled The Gallic War (Commentarii de Bello Gallico, or Commentaries on the Gallic War). In that chronicle, Caesar takes time to study the Germanic tribes, such as the Suebi, who lived across the Rhine River in what Caesar’s Latin troops knew as Germania.

It is said that they have a hundred cantons, from each of which they draw one thousand armed men yearly for the purpose of war outside their borders. The remainder, who have stayed at home, support themselves and the absent warriors; and again, in turn, are under arms the following year, while the others remain at home. By this means neither husbandry nor the theory and practice of war is interrupted.

The Germans, according to Caesar, were efficient in war and were far braver than their Celtic neighbors. They were also nomadic hunters who lived in independent tribes headed by chieftains. They loved freedom and cherished strength. They were also wild, uncouth, and utterly barbaric. Reading The Gallic War, one gets the idea that Caesar believed that he could conquer Germania, but was in no hurry to do so. After all, Caesar’s conquest of Gaul and incursion into Britannia (which was undertaken in order to suppress a pan-Celtic revolt led by politically powerful druids) got him what he wanted–land, a thoroughly loyal army, and a chance to claim Rome as his own.

By A.D. 9, the Roman Republic was no more. Thanks to Caesar’s popular dictatorship, the Roman Empire replaced the oligarchic power of the Senate after Caesar’s murder near the Theatre of Pompey. Under Augustus, the first emperor, Roman power was consolidated in Gaul, Spain, and Pannonia, while Egypt was brought under the Roman yoke. First century Romans also believed that Germania was all but conquered. The Rhine was relatively peaceful and some Germanic tribes were trading with Rome and even sending their sons to the Emperor Augustus as soldiers and mercenaries.

There was, however, one major problem. The Romans knew very little about the interior of Germania. Germanic rebels, like the Cherusci prince Arminius, who had spent many years in the Roman military, knew they could exploit this ignorance given the right circumstances.

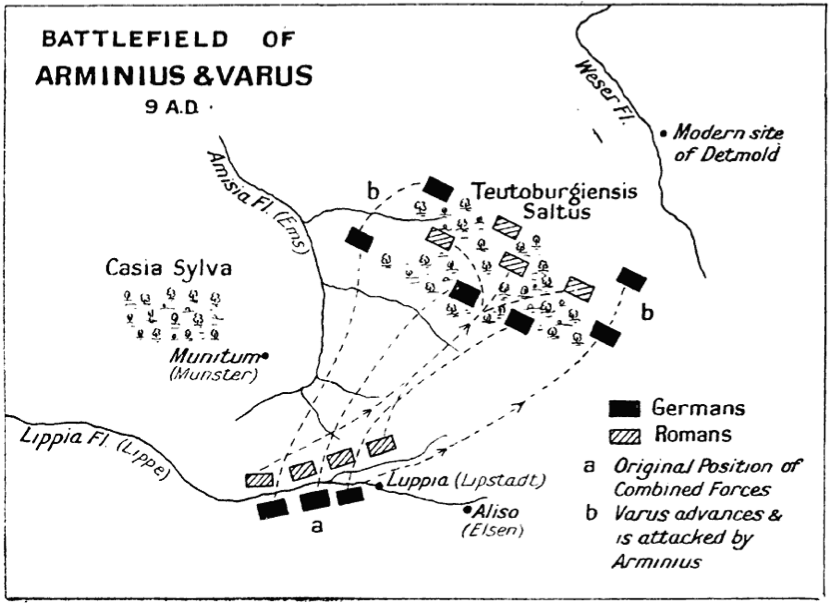

Battlefield of Arminius and Varus, 9 AD

Near the end of the summer fighting season in September A.D. 9, Varus, whom history has remembered as a better civil servant than a general, led approximately 15,000 veteran legionnaires from their summer camps along the Weser River back to their permanent barracks on the Rhine in order to be closer to a reported tribal uprising. For Varus, a veteran administrator who formerly oversaw the Roman province of Syria (which included modern day Lebanon), Germania probably did not seem as difficult to master as the frequently rebellious Middle East.

On the first day, Varus’s legions were being guided through the German wilderness by several Germanic tribal fighters loyal to Arminius. A mercenary who spoke Latin and who had previously been awarded by the Roman military for his valor on the battlefield, Arminius was a member of Rome’s knight class and was even a Roman citizen. In short, he did not look like a potential traitor to Roman eyes.

Unbeknownst to Varus and his men, Arminius sought to become the chief of his tribe. To do so, Arminius designed a way to defeat the Romans and gain the respect of his fellow Cherusci warriors. Using a false rebellion as his cover, Arminius talked Varus into leading his army into unfamiliar territory, where an ambush would be waiting. Despite warnings from a rival Germanic chief, Varus pressed on under the belief that he and his men were indestructible.

As the march progressed, Arminius intentionally extended the Roman line by leading them through treacherous country that required bridge and road building. At some point, the Roman-German group had to fight Mother Nature as heavy storms created oceans of mud that slowed the meandering train down even further. Making matters worse was the fact that German warriors were sporadically attacking the legionnaires with spears and arrows. Whether or not these skirmishes caused heavy casualties is unknown, but it’s certain that they caused anxiety among the already exhausted Romans.

A road in the Teutoburg Forest

On the second day, Varus made the decision to head for the Roman base at Haltern. The very next day, Varus’s men entered into an area known as the Great Bog, a wide, deep marsh that was buttressed by Kalkriese Hill to the south. In such a position, the weary and frightened Romans were unable to successfully move to the open ground that they favored. With the Romans pinned down, somewhere around 18,000 Germanic warriors began attacking from all sides, leaving the Romans with no room to escape.

Realizing just how dire the situation really was, Varus decided to fall upon his sword. His fellow officers followed suit. The now leaderless Romans were slaughtered. Only a few survivors managed to flee into the woods and later to the Roman camps along the Rhine. What they told their brethren was so shocking, that, according to Smithsonian magazine writer Fergus M. Bordewich, many believed that the defeat was due to “supernatural causes” brought about by a statute of the goddess Victory who “had ominously reversed direction.”

In the aftermath, Arminius was given power over a Germanic coalition that continued to harass the Roman camps in Germania until the general Germanicus Julius Caesar, after several punitive expeditions, managed to defeat Arminius’s army in several battles near the Weser River. Under Germanicus, the Romans recaptured two of the eagles lost at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest.

The Roman commander Germanicus was the opponent of Arminius in 14–16 CE

Later, during the reign Emperor Claudius, the third eagle standard was recovered from the Chauci tribe by Publius Gabinius in A.D. 42. As for Arminius, after containing the Roman threat and defeating a rival chief named Maroboduus, he became the most powerful chieftain in all of Germania. Many believed that he was too powerful, and his death in A.D. 21 was possibly the result of a poisoning.

The Roman defeat at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest essentially established the Rhine as Rome’s furthest boundary in the West. Later politicians and generals would claim that Germania was not worth Rome’s time. It was too sparsely populated and too wild, they claimed. They were right, but unlike Rome, the Germanic tribes never promised to stop assaulting the empire.

Eventually, in the fifth century A.D., the Western Roman Empire fell due to a relentless wave of Germanic invasions. By that point, the Battle of Teutoburg Forest had become legendary among the Germanic soldiers.

A much later generation of German nationalists would call upon the battle again during the Napoleonic Wars and the various struggles to unify Germany during the 19th century, and as a result statutes dedicated to Arminius (also known as Hermann) were erected, while Arminius/Hermann fraternities sprang up in Germany and among German immigrants living in the U.S.

For Romans like the historian Suetonius, the battle “nearly wrecked the empire” and caused a crisis of confidence. Doubt seeped into every part of the imperial government. None felt the pain of anxiety quite like Emperor Augustus, who, according to Suetonius’s Lives of the Twelve Caesars (which would be later echoed by Graves’s I, Claudius), would bang his head against the palace walls and cry Quintili Vare, legions redde! (“Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!”).

One comment

nice artical and beautiful and unqiue website

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.