We all know the phrase “All roads lead to Rome”. Today, it is used proverbially and has come to mean something like “there is more than one way to reach the same goal”. But did all roads ever really lead to the eternal city?

The Power of Pavement

There was a close connection between roads and imperial power. In 27 BC, the emperor Augustus supervised the restoration of the via Flaminia, the major route leading northwards from Rome to the Adriatic coast and the port of Rimini. The restoration of Italy’s roads was a key part of Augustus’ renovation program after civil wars had ravaged the peninsula for decades. An arch erected on the via Flaminia tells us that it and most other commonly used roads in Italy were restored “at his own expense”.

And road paving was expensive indeed – it had not been common under the Republic, except in stretches close to towns. Augustus and his successors lavished attention on the road network as roads meant trade, and trade meant money.

In 20 BC, the senate gave Augustus the special position of road curator in Italy, and he erected the milliarium aureum, or “golden milestone”, in the city of Rome. Located at the foot of the Temple of Saturn in the Roman Forum, it was covered with gilded bronze.

The Golden Milestone

According to the ancient biographer Plutarch, this milestone was where “all the roads that intersect Italy terminate”. No one quite knows what was written on it, but it probably had the names of the major roads restored following Augustus’s instructions.

The Center of the World

Augustus was keen to foster the notion that Rome was not just the center of Italy, but of the entire world. As the Augustan poet Ovid wrote in his Fasti (a poem about the Roman calendar):

‘There is a fixed limit to the territory of other peoples, but the territory of the city of Rome and the world are one and the same.’

Augustus’ right-hand man, Agrippa, displayed a map of the world in his portico at Rome which contained lists of distances and measurements of regions, probably compiled from Roman roads.

Roman Milestones in the Bologna Archaeological Museum. (C Davenport)

The Roman road network bound the empire together. Senators had begun to erect milestones listing distances in the mid-third century BC, but from the first century AD, emperors took the credit for all road building, even if it had been done by their governors.

More than 7000 milestones survive today. In central Italy, the milestones usually gave distances to Rome itself, but in the north and south, other cities served as the node in their regions.

Augustus also established the cursus publicus, a system of inns and way-stations along the major roads providing lodging and fresh horses for people on imperial business. This system was only open to those with a special permit. Even dignitaries were not allowed to abuse the system, with emperors cracking down on those who exceeded their travel allowances.

The surviving part of the Milion in Constantinople. (C. Davenport)

The association between empire and roads meant that when Constantine founded his own “new Rome” at Constantinople in the fourth century AD, he built an arch called the Milion at its center, to serve as the equivalent of the Golden Milestone.

Many Roman itineraries have survived because they were copied in the medieval period. These record distances between cities and regions along the Roman road network. The “Antonine Itinerary”, compiled in the third century AD, even helpfully includes shortcuts for travelers. These types of documents were uniquely Roman – their Greek predecessors had not compiled such itineraries, preferring to publish written accounts of sea voyages.

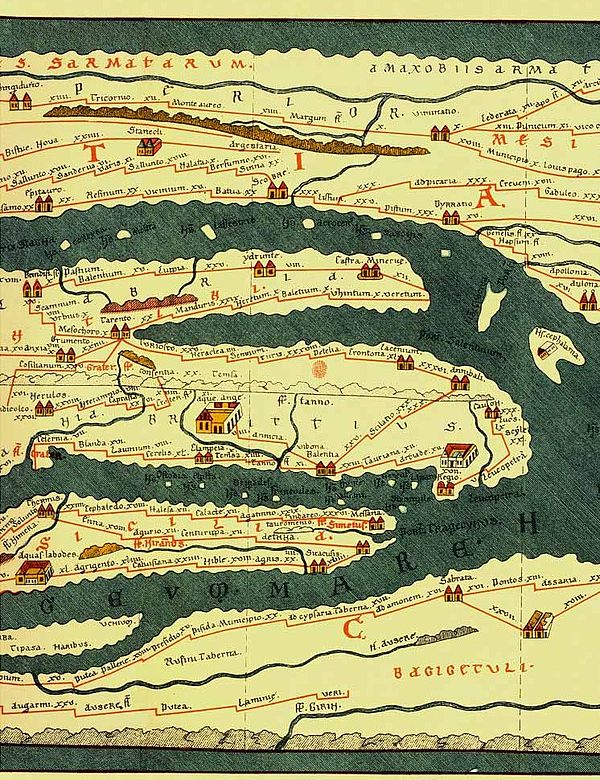

The Roman road network had prompted the development of new geographical conceptions of power. This is nowhere more prevalent than on the Peutinger Table, a medieval representation of a late Roman map. It positions Rome at the very center of the known world.

Tabula Peutingeriana (section)—top to bottom: Dalmatian coast, Adriatic Sea, southern Italy, Sicily, African Mediterranean coast

Proverbial Roads

Since antiquity, the phrase “all roads lead to Rome” has taken on a proverbial meaning. The Book of Parables compiled by Alain de Lille, a French theologian, in the 12th century is an early example. De Lille writes that there are many ways to reach the Lord for those who truly wish it:

‘A thousand roads lead men throughout the ages to Rome,

Those who wish to seek the Lord with all their heart.’

The English poet Geoffrey Chaucer used the phrase in a similar way in the 14th century in his Treatise on the Astrolabe (an instrument used to measure inclined position):

‘right as diverse pathes leden diverse folk the righte way to Rome.’

The “conclusiouns” (facts) Chaucer translates into English for his son in the treatise come from Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, and Latin – and all came to the same conclusions on the astrolabe, says Chaucer, much as all roads lead to Rome.

In both these examples, while the ancient idea of Rome as a focal point is invoked, the physical city itself is written out of the meaning. Neither de Lille nor Chaucer are actually talking about Rome – our modern “there’s more than one way to skin a cat” would work just as well.

This article was originally published under the title ‘Mythbusting Ancient Rome – did all roads actually lead there?’ by Caillan Davenport and Shushma Malik on The Conversation, and has been republished under a Creative Commons License.

2 comments

Interesting article.

Road-building in ancient Rome was as much about military prowess and communication as it was economic development. Having an intricate network of roadways allowed Rome to quickly move its armies across vast distances. For a time, this ability to transfer manpower from one place to another at speed gave Rome a superior edge in its military encounters and made its armies the envy of the world. The network of roadways also ensured imperial power and stability by allowing Rome to communicate problems such as rebellion relatively quickly from one part of the Empire to another and move its armies accordingly.

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.