By Mónica Correa, contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

While the Roman Empire bequeathed us many splendid structures, from the Pantheon in Italy to the Maison Carrée in France, there is one architectural wonder that is no doubt, the most famous of all Roman creations. The Colosseum, with its architecture, detailed structural elements and impressive history, manages to inspire awe to this very day.

Also known as the Flavian Amphitheatre, it is the largest amphitheater ever built and, interestingly, has only been called “the Colosseum” since eighth century.

Construction started under the emperor Vespasian in AD 72, with the opening ceremonies taking place under his son Titus in 80. The inaugural celebrations lasted 100 days and thousands of men and animals were slaughtered. While the Colosseum was being used it regularly housed massive performances and events that satisfied the Roman taste for savage entertainment.

Pollice Verso (Thumbs Down) by Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1872

The Colosseum’s Construction

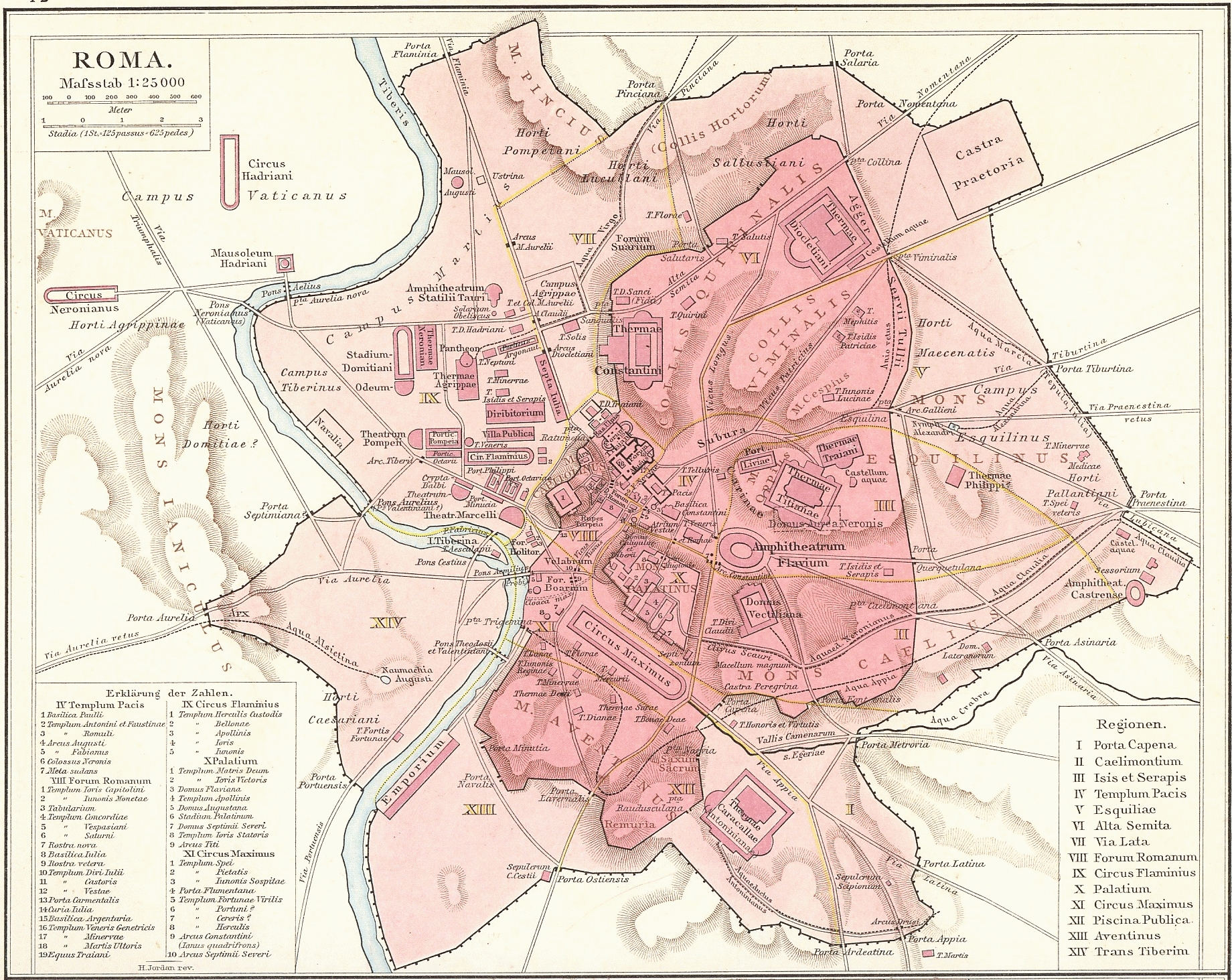

The location of

the Colosseum is very significant. Vespasian decided to build it on the grounds of Nero’s Golden House as a sign of the emperor’s fall from grace. The spot also had the added benefit of being in the center of Rome.

It took a decade to build the Colosseum and the cost of construction is unknown. However, an inscription found on the site states that funding came from Rome’s military conquests. Although its architects and builders are unknown, some records suggest that workers may have been prisoners of war.

Map of Rome during Antiquity

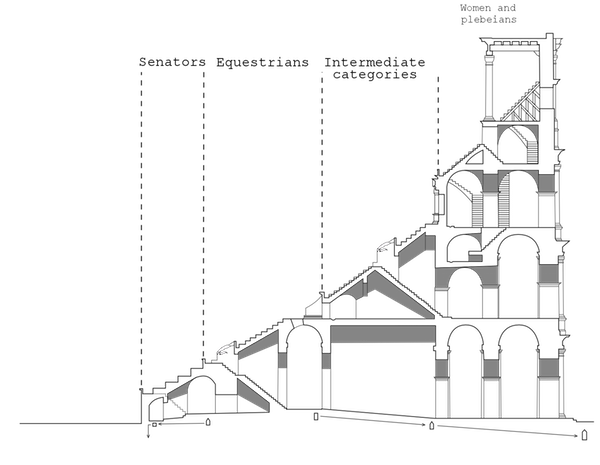

The inside of the arena measured 278 by 177 feet and was originally surrounded by seating in four separate tiers which could accommodate, according to one late Roman description, 87,000 spectators.

The seating was arranged according to the stratified nature of Roman society. Special boxes providing the best views of the arena were located at the north and south end for the Emperor and the

Vestal Virgins, respectively. Flanking them at the same level was a broad platform or podium for the senatorial class, who were allowed to bring their own chairs. The names of some fifth century senators can still be seen carved into the stonework, presumably reserving areas for their use.

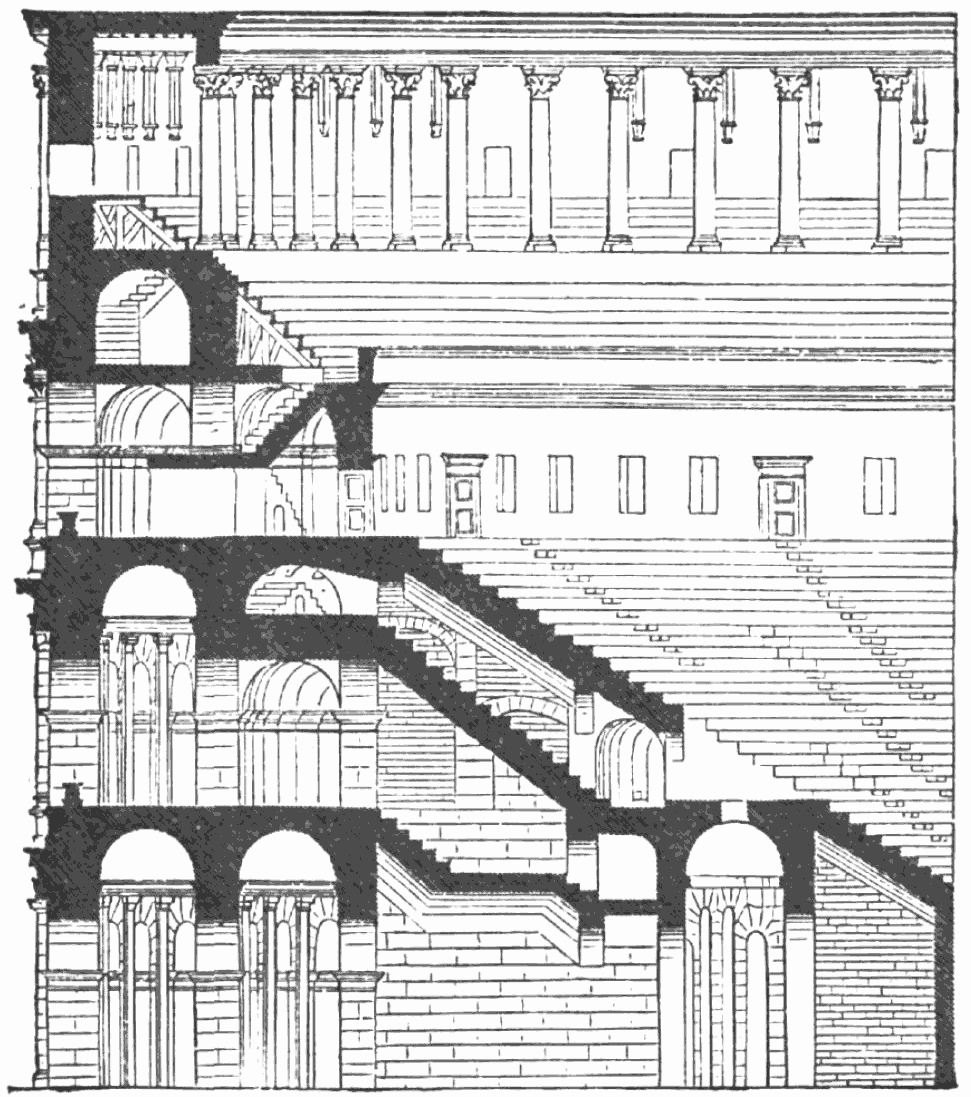

Cross-section from the Lexikon der gesamten Technik (1904)

Diagram of the levels of seating

The non-senatorial noble class or knights (equites) occupied the maenianum primum, the tier above the senators. The next level up, the maenianum secundum, was originally reserved for ordinary Roman citizens (plebeians). This was divided into two sections, with the lower part (the immum) for wealthy citizens, and the upper part (the summum) for poor citizens.

Later on a gallery was built for women and slaves. Some groups, however, were never allowed into the Colosseum. These included gravediggers,

former gladiators and, of course, actors.

The Colosseum’s Expansion

While most of the Colosseum was finished before Vespasian’s death in 79, his sons and successors completed the structure.

Sestertius of Titus celebrating the inauguration of the Colosseum (minted 80 AD).

Titus, the eldest son who ruled from 79 to 81, finished the construction for the grand opening in 80. Domitian, who succeeded him and ruled from 81 to 96, was responsible for the fourth floor, a wooden story mainly used for storage, as well as another seating gallery.

The most significant addition made by Domitian, however, was the Hypogeum, an underground complex beneath the arena. It was designed and built around two years after the Colosseum was inaugurated. Animals, performers and stagehands used this important structure, navigating the tunnels when something or someone was needed in the arena. Workers could use rudimentary elevators and trapdoors covered by sand access the stage. The Hypogeum was dark, lit only by smoky oil lanterns.

The Colosseum arena, showing the hypogeum now filled with walls. The walls were added early in the Colosseum’s existence when it was decided it would no longer be flooded and used for naval battles

Also constructed after inauguration, the awning was added as a canopy that could cover a large section of the bleachers. Its goal was to shade audiences, protecting them from the sun.

The Colosseum’s Deterioration

In 217, the Colosseum was badly damaged by a major fire that was caused by lightning, according to Dio Cassius. The inferno destroyed the wooden upper levels and it was not fully repaired until about 240. It underwent further repairs in 250 or 252 and again in 320, but never again returned to its former glory.

Interior of the Colosseum, Rome (1832) by Thomas Cole, showing the Stations of the Cross around the arena and the extensive vegetation

In the following centuries, earthquakes damaged its structure. The most significant occurred in 134, causing the outer wall on the south side completely collapsed.

The Colosseum’s Modern Symbolism

In the beginning, this structure had one important goal: to be the stage of the gladiatorial games. However, as the society and culture evolved, so did the significance and purpose of the Colosseum.

From 1928 to 2000, a fragment of its distinctive colonnade was displayed on the medals awarded to victorious athletes at the Olympic Games, as a symbol of the modern Games’

ancient reference.

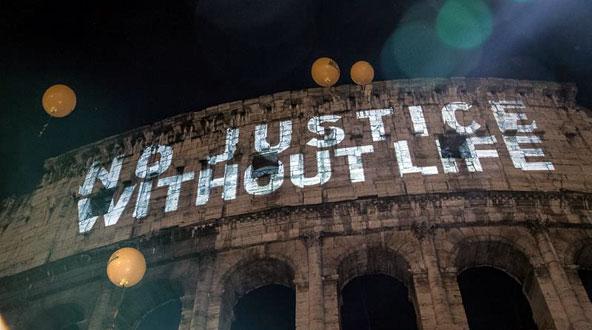

The Colosseum lights up in protest to the death penalty.

The Colosseum has also become

a symbol of the international campaign against capital punishment. As a gesture on their position against the death penalty, authorities change the color of the Colosseum’s illumination from white to gold whenever a condemned person gets their sentence commuted or is released, or if a jurisdiction abolishes the death penalty.

Today, receiving thousands of tourists from around the world, the Colosseum stands as a powerful reminder of the ancient world, its glory… and gory history.

One comment

I have been there twice, but with this added information, my next visit will be even more inspired! Thank you so much for this excellent publication!

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.