Written by Danielle Alexander, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

In Eastern traditions, this constellation is called, rather humbly, the Broken Bowl. It was the ancient Greeks that imbued it with starry mythos and royalty.

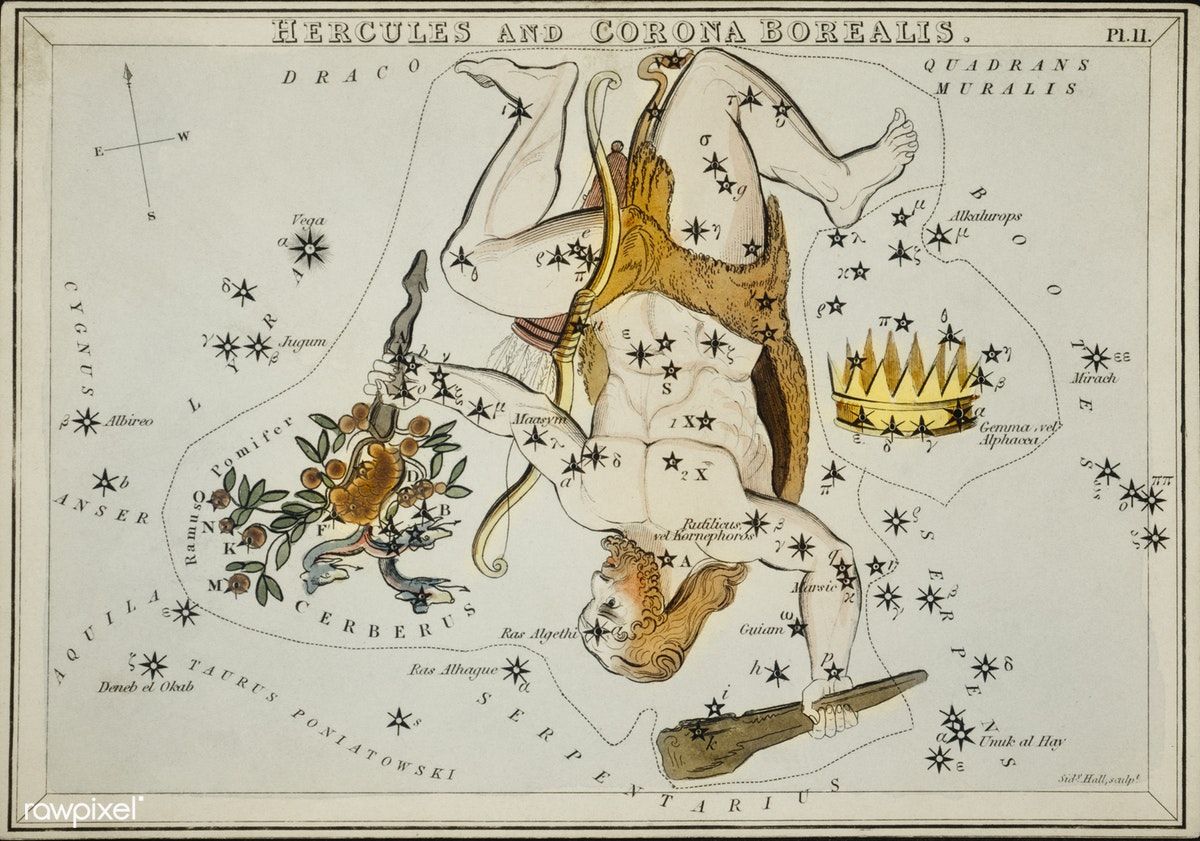

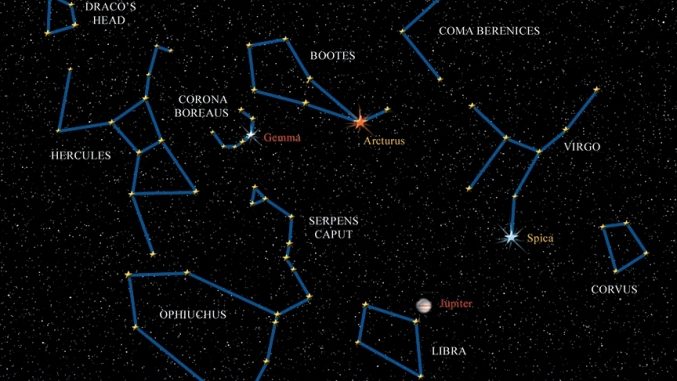

The Corona Borealis rises with Scorpion and sets at the rise of the Crab and Lion. It has nine stars in total and only three of them are considered bright, yet it is visible in the Northern Hemisphere during the evenings of late spring and early summer.

One of these stars, known as the Blaze Star, is unpredictable and flares aggressively between magnitudes. It sits between several of the human figures in the sky; the Kneeler, Boötes and Ophiuchus.

During the 2nd century BC, Hipparchus wrote The Commentary, revolutionizing the way constellations were understood by applying scientific enquiry to the stars. This eventually led to the defining of 88 official constellations, many of which have been known since Ptolemy’s The Algamest (A.D 150).

Ptolemy described traditions that had been popularized in Greek society in a wide-reaching poem by Aratus c. 275 B.C, The Phaenomena. This poem was said to heavily reference the works of Eudocus (366 B.C), lost tomes believed to contain the earliest Greek description of the skies.

The earliest surviving written accounts of the stars are the war-filled epics of Homer and cosmological fables of Hesiod (both dated roughly to the 8th century BC). However, these sources only mention major constellations like Orion, the Great Bear and the significant star clusters. That is all, and other Greek sources are remarkably silent about the skies for quite some time.

While the Great Bear has been identified in the skies since palaeolithic times, most of the constellations were defined by 1300- to 1000 B.C in ancient Babylon, and by c.400 BC, the Babylonian zodiac had been brought to Greece.

Plato encouraged the introduction of astronomy and astrology from the East and Egypt, holding the sky-watchers in high regard. At the same time, he wholeheartedly believed the Greeks would improve the imperfect, inherently unreliable system through geometry and mathematics.

The Greek system of constellations housed only eighteen star-images that did not originate elsewhere, and these are undeniably Greek, featuring heroes such as Heracles and Ophiuchus and animals like the Dolphin.

This reflects how changes in culture and society are reflected in the heavens, with the narratives developing alongside the people. As the Hermetics would say: As above, so below.

The ‘Corona’ Myth

Corona, which means crown, is the crowning wreath of Ariadne, an eternal reminder of love lost, and love found, and the mythical origins of the garland headdresses worn by women at weddings. Why? Well…

On her wedding day, Ariadne received a prized crown that later became a bridal tradition. The gift was from Aphrodite and the Horai (the Seasons), crafted of ‘fiery gold and Indian jewels’ by Hephaestus and delivered by Dionysus, who had his own seductive agenda. The rambunctious god was discouraged by a divine relative to leave the girl alone – for now.

The bride belonged to Theseus. The hero of Athens had abandoned (or was forced to leave – the sources are not clear, and the debate is still on) Ariadne after using her, and her glowing crown, to leave the Labyrinth of Crete and the city who housed it. He had stolen the princess away, and abandoned her on the next stop, so it seems preposterous that the storytellers claim that the crown was then placed into the heavens to commemorate the love of Theseus and Ariadne – talk about a rushed ending to a bad romance novel!

An alternative version sees Ariadne seduced by Dionysus after he finds her abandoned on the sands of Naxos (or Dia). She then bore the wine-god several sons: Oenopion, Thoas, Staphylus, Latromis, Euanthes, and Tauropolus.

It has been suggested that this divine marriage is due to the vine-cult reaching mainland Greece through Crete, where Ariadne was understood to be a moon-goddess and their children ancestors of several island tribes. Dionysus grieved greatly when she passed to the Underworld and placed her wedding wreath in the sky as an eternal memorial.

But Maybe It Isn’t a Bridal Crown?

Another variant sees the crown as Theseus’, hence its placement beside him in the sky (the Kneeler). Dolphins guided Theseus when the hero dived into the Cretan harbor to retrieve the ring of Minos during an informal, yet no less important, trial to prove his divine parentage.

The jury’s still out as to whether Theseus was gifted the crown by Thetis, famed mother of Achilles, or Amphitrite, the little-known wife of Poseidon. Either way, the sea presented Theseus, a descendant of Poseidon, with the crown. It was an early wedding gift, so when Theseus wed Ariadne, he gifted it to her.

Alternatively, Dionysus sought to return his mother, Semele, to the world of the living. On his quest, he met Polymnos in Argos who claimed to know the route to the Underworld and soon led the way. However, Dionysus feared that the Underworld would taint the gorgeous golden crown he carried, so he deposited it for safe-keeping at a site henceforth known as Stephanos. After he retrieved Semele, he cast the crown to the sky. This tale feels incomplete and there is very little to confirm it.

Mythic Wordplay

The etymology of Naxos involves several theories; Homer’s usage of dia could indicate that Naxos was the ‘isle of the Goddess’ as Dia was known to be its’ capital town, however, the name could also derive from naxai (sacrifices), strongly connected to the thysai (rites) of the island as there were many pious sacrifices made to honour the gods.

The connection between ‘crown’ and ‘dia’ sparked further etymological curiosity within me – was there an etymological route for the word ‘diadem’?

Interestingly, the root of the word is connected with the Greek diadema (the headband worn by Persian kings, adopted by Alexander the Great and his successors, enforcing the regal attachment to the band) but also has links to ‘bind across’/’throughout’/’twice’. Ariadne was indeed bound throughout, either by fate or marriage vows (of which she has two).

Wedding Rites

Weddings in the ancient world were infused with religio-cultic elements that were believed to enhance fertility, provide protection and purification to the couple as well as strengthen their bond. The wedding procession began at the bride’s house and ended at the groom’s, literally following the passage from one home to another.

These rites could last several days and usually took place just before the new moon. Specifically, the moon of the month Gamelion (January/February), which was named after deities presiding over marriage protection; Zeus, Hera, Aphrodite, Peitho and Artemis (according to Plutarch). A festival occurred in this month, of the same name, and was celebrated around the same time as modern Valentine’s Day to symbolize the sacred marriage of Zeus and Hera (despite its countless flaws).

On their wedding day, brides would offer personal possessions or a lock of her hair to Hera or Aphrodite and wear a veil and wreath until the feast, which had been provided by her father, was finished. The couple-to-be-wed would bathe according to custom in a ritual called λουτρὸν νυμφικόν, loutròn nymphikón.

A young boy who had not experienced the death of his parents (therefore representing vitality and strength) would walk behind the couple during their ceremony, “wearing a wreath of thorny plants intertwined with acorns, [and] carried a basket and distributed bread to the guests, reciting the words: ἔφυγον κακόν, εὕρον ἄμεινον” (I have escaped evil and found something better). This symbolizes the increased prestige provided by marriage and has been argued to be reminiscent of the nomadic hunter-gather transitioning to civilized community cult rituals.

Further homely rites occur, led by the bride as she invites the home to accept her and for protection and fertility including: plate smashing, honey and sesame seed cake distribution, showering in nuts, and, in Sparta, the shaving of ones head and wearing of mens’ clothes in order to deceive maleficent spirts.

During these unprecedented times, it can be hard to associate the word corona with light, love and royalty. However, these tales display how the words can change over time. They show how many perspectives can arise about a singular topic, how different yet similar they are – as if to fit this theme, this is not the only Corona constellation in the sky! More on that later, but for now, let us allow the Corona Borealis constellation remind us of beauty, love and strength.

One comment

Hallo there to whoever is going to read this,

I’m sometimes wondering about the stars myself. It’s something that seems to be human…

I’m also sometimes wondering if the old Greeks also wondered about star travel because they have invented starsigns for beings like Pegasus as well as for some heroic people…

Perhaps they also thought that they would be able to travel space after their earthly lives…

Was this a case of Platonic thought where everything that exist have imperfect and perfect forms?…

Is that why Plato, who was also a mathematician, thought in such mystic ways, as well!?

Can one know such things, fully?

Here are some of my thoughts:

I’m sometimes wondering about what the Greeks thought about time and distances space…

How, and when, did they start Euclidean Geometry in their astronomy?

Are We Alone?

____________________

Are there gods? They’re most probably the product of some people’s fruitful imaginations…

But, are we alone?

Are there any aliens, or none at all?

Is the other question to be asked…

Are there alien civilisations, somewhere in space?

When will technology enable us to at least see?

Travelling space is, at this moment in time, just a dream…

A human that’s able to travel space will have to be evolved, genetically engineered,

else such future travellers won’t survive any long trip…

A human being that’re evolved to live on Earth, like us, will be unfit for and unequipped to last in space for many years…

How can we be alone; how can there be no one out there, in the vastness out there?

When will we be able to satisfy our curiosity by knowing such things forsure?

When will we be able to still our fears concerning such issues with real knowledge?…

Humanity has asked such questions for millennia;

they are burning in the collective heart of man, ever since he realised that he he is not just an animal; but, that he is somewhat different, although still one, all the same…

Humanity has always feared the unknown, but he has always wanted it too, because such conflicting emotions are bringing out the best, and the worst, out of mankind;

Such emotions are making them to feel alive…

Humanity has built huge monuments, beautiful pieces of extraordinary art; and has spilled a lot of blood, in his persuit of the unknown, and the gods…

Pieter J (PJ)

(Edited)

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.