Written by Danielle Alexander, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The horse features relatively heavily in Greek mythology, with Hesiod referring to a horse during his invocation to the Heliconian Muses at the start of his Theogony.

Thus it comes as no surprise that the ancients, who placed their greatest stories and symbols in the night sky, identified a horse by the name of constellation Pegasus. Yet which myth does it refer to? That, of course, is a trickier question.

It could be a reference to a metamorphosed maiden named Hippe, having taken the equine shape when fleeing her father, knowing he would violently disapprove of her out-of-wedlock pregnancy, despite its divine lineage – the young girl had been seduced by a son of Helen of Troy, Aoiles.

Artemis, feeling pity for the woman who had been pious for so many years, hid her in the sky. The backside of the horse is never seen as to conceal her female form.

A total of 18 stars create this half-horse constellation, its equine shape identified by a distinctive square. (Equine is taken loosely, for the ancients had creative imaginations and I have to strain to find the “horse”.)

Its most famous star is Andromedae, located in the north-eastern corner of square, but its brightest star has Arabian etymology. It is known as Homam (“lucky star of the hero”), potentially memorializing an Arabic hero said to have mounted the divine steed, or sometimes as Hammam (‘whisperer’) in reference to the secret ancient art of horse whispering.

This constellation can be seen galloping into midnight culmination during September in the Northern Hemisphere and some middle-latitude Southern locations.

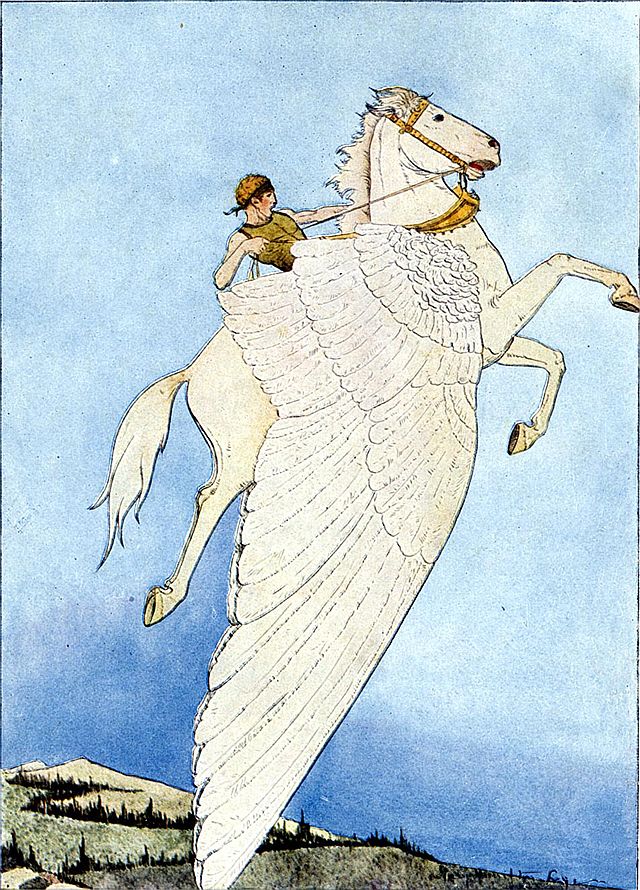

Anonymous ancient sources claim it could potentially portray Pegasus, the winged steed of Bellerophon that sprung from the head of Medusa, despite a lack of twinkling wings.

The story goes that a Greek queen by the name of Anteia fell in love with hero Bellerophon, but he refused her advances. In retaliation – and fear he would speak of the incident to her husband – she accused Bellerophon of rape. Fortunately for the accused, the King had taken a liking to the man and did not wish to punish him directly.

So, he gave Bellerophon a seemingly impossible but highly honorable task: to defend the king’s daughter’s honor against the torturous Chimera.

Against all odds, Bellerophon was victorious, but ultimately committed hubris – he sought to transgress the realm of mortals to reach the home of the gods, Mount Olympus. He was hurled from his horse at the boundary. As Bellerophon cascaded through the sky to his death, the story goes that the horse sailed through the heavens and remained in the stars.

Greek astronomy

The Greeks were not alone in their desire to find familiar things among the twinkling stars of the mysterious abyss above us. Astronomical knowledge has been identified in prehistory, arising from the observation and tracking of the stars to situate peoples and their cultures within the cosmos.

Narratives then evolved over time, with the earliest Greek sources being Hesiod and Homer, valued highly for their insight to ancient cosmology. The constellation narratives developed slowly, from generation to generation, and likely took form during the transition from oral to written transmission, but to what is extent is unknown.

Myth is both molded by culture and molds it, predominantly through art – Classical astronomical art is still recognized in modern astronomical artwork and naming processes.

Today, there are 88 constellations officially recognized by the International Astronomical Union, and many of them have been accepted since Ptolemy’s The Almagest (A.D 150). Constellations often originate in older lands, defined by the Mesopotamians between 1300-1000 BC, but the Greek astral mythos canon was solidified by Eratosthenes in a work now lost to us.

Even though the Greeks were late to the constellation conversation (500 BC) – and received a lot of their knowledge from their Eastern neighbors – it was the Greeks that introduced the word katasterismos or catasterism; the process of being set in the heavens. Despite knowing many constellations for the purposes of navigation and indication of seasonal change, many extravagant mythic connections were added later.

Horse history

The horse was domesticated on the Eurasian Steppes during the 4th millennium BC and gradually dispersed through the Near East and Mediterranean. The domesticated horse was expensive to purchase and maintain, yet quickly became important in many aspects of the ancient life (warfare, travel, sports, and hunting), despite being largely limited to the privileged class.

The second-highest rank in Athens was that of hippeis or ‘horse-owner’; therefore, the horse was a status symbol. Chariot racers were also very popular and took place in arenas known as ‘Hippodromes’. There were also other equid-related sporting activities, such as horseback acrobatics and horseback javelin throws.

It was said that Poseidon was the father of all horses, so they were often ritually sacrificed through drowning, and most frequently in funerary ceremonies. These customs, predominantly displayed in Homer’s Illiad with the extravagant funeral of Patroclus, can be dated back to Mycenaean times.

For the modern reader, the horse is no longer a vital part of daily life. Horses are associated with the countryside, a different lifestyle than the one most of us are used to. Or they are simply kept in paddocks and rode along country roads. Thus, it’s easy to lose sight of the importance of the horse for the ancients and why it features heavily in mythologies across the world.

Through astronomy, the ancient Greeks immortalized the horse, providing it with an eternal field of stars to gallop through, its mane flowing in the abyss of night.

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.