by Kevin Blood

I remember lining up with my younger brothers on the linoleum floor of our kitchen, ready to receive a spoonful of foul-tasting cod-liver oil and another of some vile milky tonic, whose name escapes me. Both made me retch from my boots. I thought my mother was trying to poison me! These vomit-inducing preparations were thought by her to be good for whatever might ail us. Great preventatives and cure-alls! She has been active in her search for cure-alls over the years, a search that occupies many mothers conscious of the well-being of little children.

Particularly valued by her are concoctions that protect and promote overall health and vitality, purify toxins in the body, grant a sense of tranquillity and provide relief from pain and discomfort. From ancient to medieval times a prized cure-all, named theriac, was thought to be effective in eliminating harmful toxins, in the form of venom or poison. It was said to heal a wide range of maladies. While researching its history, how it was tested and the ingredients it contained, I am relieved my mother did not know about this ancient wonder drug.

Theriac finds its roots in the story of the wily King Mithridates Eupator VI (120-63 BC), King of Pontus, in Asia Minor. Mithridates, described by Velleius Paterculus as ‘ever eager for war, of exceptional bravery, always great in spirit and sometimes in achievement, in strategy a general, in bodily prowess a soldier, in hatred to the Romans, a Hannibal’. He was a thorn in the side of the early Roman republic, an adversary of Sulla, Lucullus and Pompey. Ambitious, he rose to power by murdering his brother and imprisoning his mother. His ambition and courtly intrigues meant he feared assassination by poisoning.

Fascinated by the idea, he tested poisons on slaves and criminals to observe their effects. As a protective measure, he consumed small doses of poisons and venoms, as well as their antidotes. Mithradates tasked his physician, Crateuas, to create a wonder treatment effective against poisoning. Crateuas worked with Persian magi, Scythian shamans, and other physicians, to create Mithridatum, an electuary; a mixture of powders in paste form, combined with honey as a binding agent to create a pill. The pill, a mixture of approximately 40 ingredients, was taken daily by Mithridates. It was claimed to be effective against arsenic, and the toxins created by vipers, sea slugs, and scorpions, including a variety of other toxins.

It may have been effective: the sources assert Mithridates lived in good health until his seventies. While waging war against Pompey, he was betrayed by his son. Rather than face capture, he committed suicide. Having built resilience against poisons, he ordered a slave to stab him to death. Pompey took his papers, including the recipe for Mithridatum, back to Rome and translated them into Latin. Thus, the medicine named after him was adapted and became known as theriac. The name theriac means ‘to do with wild beasts’. This medical preparation remained popular right into the mid-eighteenth century.

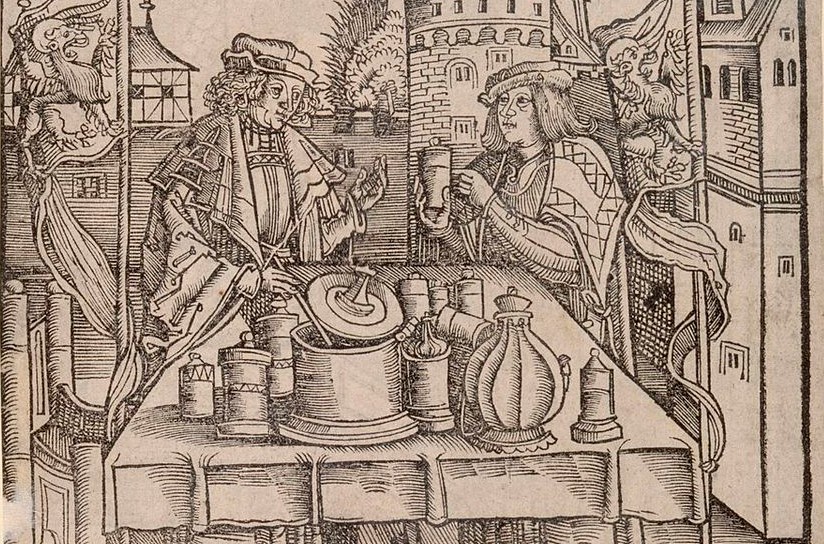

During the Renaissance, Venice came to produce the best quality theriac, known as Venice (or Venetian) treacle. It carried the official seal of the republic, a guarantee of quality. Amongst the European medical community of the time, there was much debate over the quality and efficacy of the theriacs. The question being, were the modern preparations as good as those of the classical era? Some thought difficulties in procuring many of the ingredients available in ancient times meant contemporary theriacs were ineffective, others that ignorant or negligent physicians were to blame for poor-quality production. Such was the concern that in some European cities, the manufacturing of theriac was done in public, under the supervision of a recognised physician. This was conducted under strict controls and standards, essentially an early medical regulatory framework. Renaissance physicians sought out genuine classical descriptions for the ancient ingredients and production methods of theriac.

Ancient theriac first played a role as an antidote. Later, it became a panacea for a variety of illnesses. Given the nature of ancient pharmacology, more than one formula existed. One of the oldest, described by the naturalist Pliny the Elder and later by Galen of Pergamum, physician to Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, originates from inscriptions found at the temple of Asklepios at Kos, a major centre of the healing cult. Its ingredients contained oppnax (sweet myrrh) thyme, fennel, parsley, and aniseed. One ingredient in many ancient preparations of theriac was opium, the juice of the poppy plant.

An ancient standard for the formulation of theriac was that of Andromachus, AD first-century botanist and court physician to the emperor Nero. Andromachus claimed his theriac superior to Mithridatum because it contained some sixty-four ingredients and was enhanced by the flesh of a viper and a much higher quantity of opium. For Andromachus, his ‘tranquillity’ theriac, unlike Mithridatum, was effective against poisons and venoms, and good for treating colic, dropsy, animal bites, plague, and inflammation.

Galen describes the basic formula for his theriac, based on Andromachus’, in De Antidotis I, De Antidotis II, and De Theriaca ad Pisonem. It contained vipers’ flesh, cinnamon, wine, honey, opium and more than seventy other ingredients. It matured for years and was administered in plaster form or orally. Galen, not one shy of self-promotion, claimed his formula was superior to all others.

What Andromachus’ and Galen’s versions of theriac have in common is the complexity of preparation, the wide variety of ingredients, and the rarity and great expense of some of its elements. It is reasonable to assume the version found at Kos was more affordable for the average pilgrim.

We can guess at how expensive some versions of Andromachus’ theriac were to produce from Galen’s treatise Peri alupias (Avoiding Distress), a text lost to us until as recently as 2005. It describes how he remained calm after a fire in Rome, AD 192, caused the loss of many of his prized possessions. The fire destroyed the library on the Palatine Hill, and some of the imperial archives and expensive real estate and storehouses on the Via Sacra. Galen lost precious metals, credit notes, medical instruments, medicines, and ingredients for producing more of these and 80 Roman pounds of his theriac.

Galen prescribed daily doses of his theriac for Marcus Aurelius; the ancient sources, including Aurelius himself, describe the emperor suffering for much of his adult life from ill-health. He had ulcers and impaired breathing. In the composition of Aurelius’ Meditations, it is interesting to speculate how daily quantities of opium may have contributed to the sense of Stoic detachment from perturbation, and the dream-like quality of his cosmic speculations about the nature of the universe.

Perhaps the book should have been called Medications, after all!

Sources

Houston, G.W. (2003) ‘Galen, his books, and the Horrea Piperataria at Rome’, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, vol. 48, pp. 45–51 [Online]. Available at https://www.jstor.org.libezproxy.open.ac.uk/stable/4238804 (Accessed 26 January 2022).

Karaberopoulos, D. Karamanou, M. and Androtsos, G. (2012) ‘The theriac in antiquity’, The Lancet. Science Direct, Elsevier Ltd. Available at: The theriac in antiquity – The Lancet (accessed 26 January 2022).

Karamanou, M. and Androutsos, G. (2019) Chapter 12 – Theriaca Magna: The Glorious Cure-All Remedy, Editor(s): Philip Wexler, In History of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Toxicology in Antiquity (Second Edition), Academic Press, pp. 175-184. Available at: Theriac – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics (accessed 26 January 2022).

Mayor, A. (2019) Chapter 11 – Mithridates of Pontus and His Universal Antidote, Editor(s): Philip Wexler, In History of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Toxicology in Antiquity (Second Edition), Academic Press, pp. 161-174, ISBN 9780128153390. Available at: Theriac – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics (accessed 26 January 2022).

Nutton, V. (2012) ‘Galen and Roman medicine: or can a Greek become a Latin?’, European Review, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 534–42 [Online]. Available at https://journals.cambridge.org.libezproxy.open.ac.uk/article_S1062798712000105 (Accessed 26 January 2022).

Nutton, V. (2014a) ‘Avoiding Distress: translation’ in Singer, P.N. (ed.) Galen: Psychological Writings, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 77–99.

Nutton, V. (2014b) ‘Avoiding Distress: introduction’ in Singer, P.N. (ed.) Galen: Psychological Writings, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 45–76.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.