By Alicia McDermott, Contributing writer, Ancient Origins

An unpunished second-generation Titan of Greek myth, Helios was a deity who was important, but not always recognized for his powers. Until his role was usurped by a newer god, Helios was the deity of the life-giving, season-changing sun. He appeared in artwork riding his horse-drawn chariot across the sky and was a firsthand witness to several major events in the lives of other gods and goddesses, but Helios generally seemed to pass along in the background, seeing everything going on both on earth and in the heavens as he made sure to follow his daily routine.

Titans, Nymphs, Kings, and Oceanids: Helios’ Extensive Family

Helios’ parents were the Titans Hyperion, god of light, and Theia, goddess of sight. His sisters were Selene (the Moon) and Eos (Dawn). He was born/created in what is called the Golden Age of Greek Mythology and was responsible for bringing light to the world as the god of the sun. That role would gradually be usurped.

‘Helios as Personification of Midday’ (1765) by Anton Raphael Mengs.

His lovers include the Oceanids Perseis (whom some sources call his wife) and Clymene as well as the nymphs Crete and Rhodes.

His daughters with Persis include the famed sorceresses

Circe, a lover to Odysseus, and Pasiphae, King Minos of Crete’s wife. His two sons with Perseis were King Aietes (Aeete) of Kolchis (

Colchis) and King Perses of Persia.

Phaethon was his son born from Helios’ relation with Clymene and he had three (or five) daughters with her, known collectively as the Heliades.

‘Helios and Phaeton with Saturn and the Four Seasons’ (1635) by Nicola Poussin.

With Rhode, Helios had seven sons, the Heliadae, and a daughter named Electryone. These sons were said to have been smarter and stronger than any other men and soon became the rulers of Rhodes. Three of the main cities, Ialysos, Cameiros, and Lindos, are said to be named for three of his sons.

Two of his nymph daughters, Lampetia and Phaethusa, were in charge of overseeing his cattle on Thrinacia.

Helios in Art – How Did the Ancients Depict the Greek Sun God?

Helios appeared in all kinds of Greek art. He’s generally depicted as a young man wearing a crown of the sun’s rays, or with bright, curly hair. His piercing eyes reflect the legends of his all-seeing gaze and he’s clothed in a garment fit for a god. A simpler Greek symbol for Helios is a large haloed eye.

The poet who authored the 31st Homeric Hymn presents a beautiful description of the sun deity’s appearance in artwork:

“As he rides in his chariot, he shines upon men and deathless gods, and piercingly he gazes with his eyes from his golden helmet. Bright rays beam dazzlingly from him, and his bright locks streaming from the temples of his head gracefully enclose his far-seen face: a rich, fine-spun garment glows upon his body and flutters in the wind: and stallions carry him.”

Relief showing Helios, sun god in the Greco-Roman mythology. From the North-West pediment of the temple of Athena in Ilion (Troy). Between the first quarter of the 3rd century BC and 390 BC. Marble. Found during the excavations lead by Heinrich Schliemann in 1872, now in the Pergamon-Museum in Berlin, Germany.

Usually the sun god is shown riding his golden chariot at the edge or in the background of someone else’s scene. His chariot is drawn by four winged horses, or sometimes dragons, and he is sometimes accompanied by one or both of his sisters.

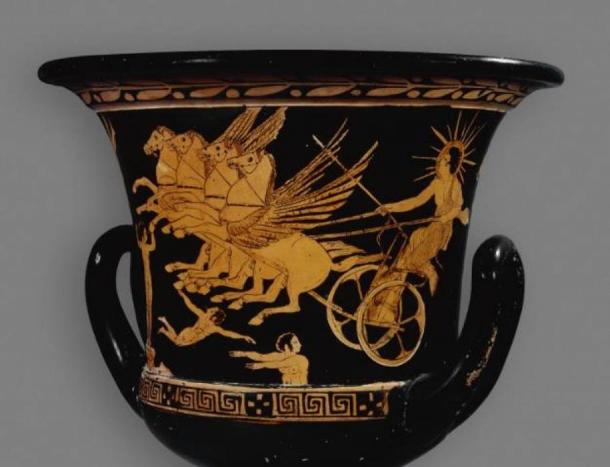

His image has been identified in several examples of Greek pottery dating to the 5th and 6th centuries BC. For example, Helios is depicted on a red-figure calyx-krater from 420 BC, in which boys symbolizing the stars fall towards the ocean as he approaches. He’s also represented in some Heracles’ scenes on 6th century BC black-figure and 5th century BC red-figure pottery.

Helios on a red-figure calyx-krater from 420 BC.

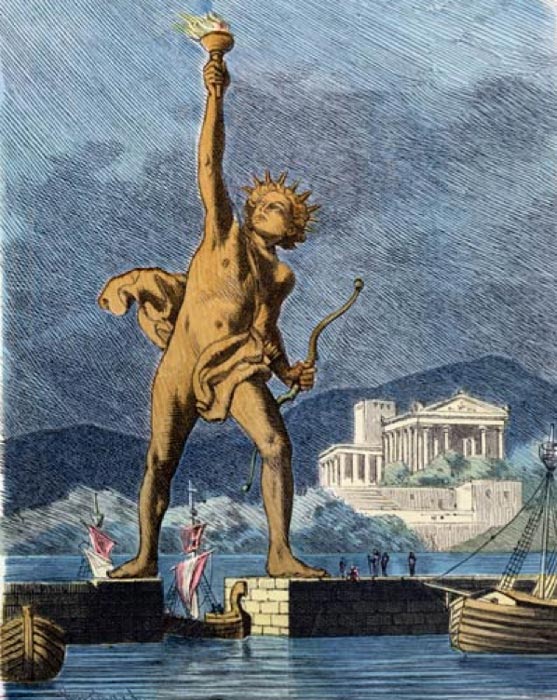

The most famous example of Helios in art, however, was the

Colossus of Rhodes. This massive standing figure was one of the

Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. It was constructed between 304 and 280 BC, but toppled over during an earthquake in either 228 or 226 BC. Coins from Rhodes also presented their patron deity for centuries.

Some notable historic figures also took on the likeness of the Greek sun god in their portraits.

Alexander the Great and the Roman emperors

Vespasian and Nero all desired to be seen as incarnations of a sun god.

Alexander the Great as Helios. Marble, Roman copy after a Hellenistic original from 3rd–2nd century BC.

His Daily Journey Across the Sky

The most important ancient Greek myth of Helios is his daily journey. The ancient Greeks believed that there was a golden chariot of the sun that was so bright that human eyes could not bear to gaze upon it. For them, that chariot was driven from the east (Ethiopia) to the west (Hesperides) across the sky every day by the god Helios.

The journey was difficult and it was believed that Helios was a skilled charioteer to be able to not fly too close or distant from the earth. Helios’ daily trip across the sky began as his sister Eos (as dawn) threw open the gates of his beautiful eastern palace. He set off with his four winged horses (Aethon, Aeos, Pyrois, and Phlegon). The long travel had a steep ascent, peaked around mid-day, and then steeply descended towards his western palace, where his nephew, Hesperus (evening) awaited him.

Three paintings showing three deities of Greek mythology as personifications of the times of the day. From left to right: Helios (or sun god Apollo) personifying Day, Hesperus embodying Evening, and Selene (or Diana, Luna) personifying Night or the Moon.

To return to the eastern palace, Helios was believed to have sailed under the world via the northerly stream of the realm of Oceanus with his horses and chariot in a golden boat (or large cup/goblet, or bed) created by the master smith and deity, Hephaestus. While Helios was hidden in Oceanus, Selene, the moon goddess, took her turn to cross the sky.

Minor Roles for Helios in Greek Myths

Another well-known myth involving Helios was when his son almost destroyed the earth. A popular version of the Greek myth of Phaethon says that the young man wanted proof that the sun was his father, so he went east to test the deity and ask him for a gift. Helios agreed to give his son whatever the youth wanted, but was distressed to discover Phaethon wanted to take a turn driving the golden sun chariot across the sky. He reluctantly consented and that favor turned into a disaster.

Phaethon could not control the winged horses and spun out of control, hurtling too far, then far too close, to the earth. Some of the world froze and other parts were set on fire as Phaethon struggled to control the chariot. But it was too much for him and as the gods watched the chaos unfold it was decided that something must be done before the earth was destroyed.

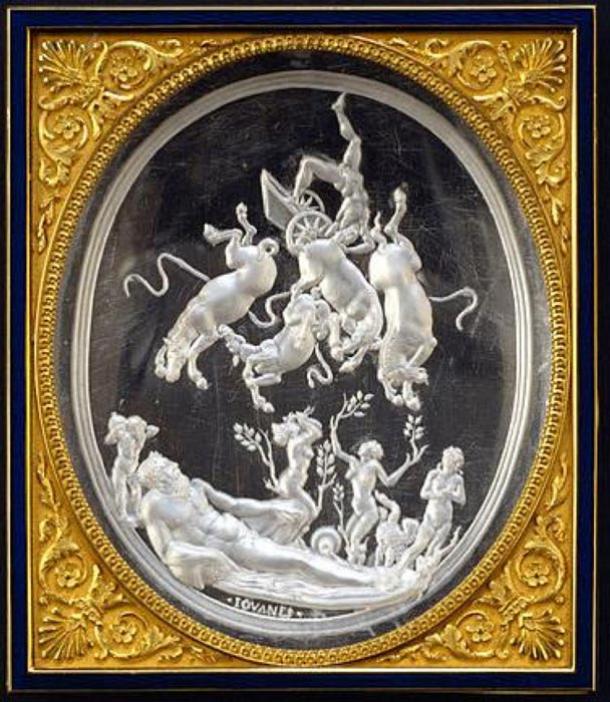

‘The Fall of Phaeton’ (1531-1535) by Giovanni Bernardi.

Zeus saw no other option than to strike Phaethon down with a thunderbolt. The gods had to beg Helios to return to his work following the death of his son, but the sun god eventually agreed. And Phaethon’s sisters, the Heliades, were in such despair due to their brother’s death that their tears turned into amber and they became poplar trees.

Helios also played a minor role in many Greek myths. For example, his power to see everything on earth and in the heavens made him an eyewitness to the abduction of Persephone by Hades and the affair between Aphrodite and Ares.

Helios (as Sol) shows the other gods Venus and Mars (Aphrodite and Ares), Vulcan (Hephaestus) stands at the front of the painting. (1540) by Maarten van Heemskerck.

He sometimes offered his assistance to other characters in Greek myth, such as when he allowed his granddaughter Medea to flee on his chariot after she murdered her children. He also lent his golden ship/cup to Heracles when the Greek hero had to cross Oceanus and capture the cattle of Geryon. Helios rescued his friend Hephaestus from the battlefield during the Gigantomachy and restored Orion’s eyesight after he was blinded by Oenipion as well. The earth mother goddess, Gaia, also sought his aid in warming and drying her when the land had been frozen by the remains of Typhon.

But Helios also showed his vengeful side when he appeared in the epic Greek tale, the Odyssey. After Odysseus’ men fed upon Helios’ sacred cattle he was so angered he had Zeus strike Odysseus’ ship with a thunderbolt – Odysseus was the only survivor of the attack.

The Cult of Helios

In Classical Greece, Helios was openly worshipped in Rhodes, where he was considered their patron deity since at least the early 5th century BC. Legends said that Helios was the first to see the island emerge from the waters and claimed it as his own. The island’s name came from Helios’ nymph lover, Rhodos. Every five years the island held PanHellenic games called the Halieia and a chariot and four horses were thrown into the sea as an offering to Helios.

While he was worshiped on Rhodes, it seems that Helios was not a major cult deity in the rest of ancient Greece. Temples of worship have not been mentioned to any extent, perhaps due to a belief that ‘barbarians’ built temples of worship to the sun. Nonetheless, his name was invoked in serious oaths and Plato wrote that Socrates and others would greet and pray to the sun every day.

‘The Colossus of Rhodes straddling over the harbor’ (1886) painting by Ferdinand Knab.

Helios vs Apollo and Sol – Who was the Real Sun God?

The Greek Titans fell and the Olympians arose. Helios was not punished after the Titanomachy, but ancient Greeks pushed his role as the sun god towards someone else – Apollo.

It seems that the radiant and pure god Apollo began to gradually take over the role of sun god beginning around the 5th century BC. By the Hellenistic period the transition was almost complete. Apollo and Helios had become almost synonymous.

The Romans transformed Helios/Apollo into their sun god, Sol, and decided it was time for the deity to take a more important cult role. The Circus Maximus of Rome even had a temple dedicated to Sol and Luna (the Moon) from the 3rd century BC.

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.