By Ben Potter

There is (at least) one important step between the birth of western literature and the age of modern prose… and that is the genesis of the novel.

Here we are hot on the heels of our recent look at the ancient novel in the guise of Daphnis and Chloe, a bucolic idyll of star-crossed love. The twisted account under scrutiny today, however, could not be further from the beauty, purity and innocence ubiquitous within the previous work’s pages.

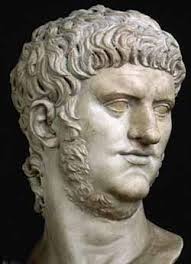

The founding text in question is the Satyricon, written by Gaius Petronius Arbiter in the 1st century AD during the reign of the emperor Nero.

If the finicky or pedantic wanted to poke holes in the above summary, they might point out that the Satyricon may not have been, in fact, the very first novel. Neither perhaps was it written by Petronius… nor in the reign of Nero.

Oh, and possibly, it wasn’t even called the Satyricon, as it is sometimes labelled as the Satyrica.

Though, of course, the attribution and date go hand in hand.

To give us some firmer ground on which to stand, we can state that Petronius was unquestionably a member of the Neronian court (famously represented by Leo Genn in the motion picture Quo Vadis). Moreover, chronicles of his lavish, lazy, witty, hedonistic and amoral character make him a good match as a potential author of the risqué Satyricon.

Because the style of the novel strongly suggests it is Neronian and there is no other viable candidate to whom we can attribute the work, Petronius almost ascends to the title of authorship simply by a process of elimination.

Though despite evidence of undoubted, and occasionally high-brow, literary skill, Petronius (well.. his mother anyway) may have welcomed the fact that his name is on the cover in pencil rather than ink.

The Satyricon is lubricious, grotesque, subversive, picturesque, imaginative, and perverted in almost equal measure.

One can imagine it being something Roman Senators hid under their mattresses, passed around at the bathhouses and only read in public when concealed in a dust-jacket of Aristotle’s Ethics.

Therefore, as if you hadn’t twigged already, this might be a good point at which the prudish should stop reading.

The fragmented remains of the story (there are guesses that the c.200 pages could have run to as many as 1000) concern the trials, trysts and tribulations of the narrator, Encolpius and his lover, an astoundingly beautiful 16-year-old servant-boy, Giton.

As much of the work is missing, it is unclear as to the origins of the men, but it has been conjectured that Encolpius and his fair-weather friend (and constant rival for Giton’s affections), Ascyltus, could be runaway gladiators.

The extant work begins with the three men lying, stealing and… well… shagging their way across the south of Italy.

However, the bawdy and carefree tone is often punctuated by moments of acute and alarming earnestness.

The culmination of an orgy scene instigated by Quartilla, an acolyte of the fertility god Priapus, sees a soldier bursting in whilst Giton is (consensually) deflowering a remarkably young virgin. The solider is on the brink of assaulting both juveniles before being called away to deal with unrest in the street.

These sobering moments punctuate what is an otherwise amusing and light-hearted work as Encolpius and Giton take the guise of a homosexual, hedonistic and hubristic Laurel and Hardy; forever falling out of the frying pan and into the flaming fire.

Then there is perhaps the most famous passage in the entire work, indeed one of the most famous passages in all of ancient literature; the Cena Trimalchionis, the dinner of Trimalchio.

The resonance of this vignette is probably felt more tenderly than we realize.

F.Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby went with working title’s of Trimalchio and Trimalchio in West Egg, before a less esoteric choice was made. Likewise, T.S. Eliot quotes directly from the passage in The Waste Land, while a reference is made in Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. And, more recently, it is called upon in Robert Harris’ superbly written Pompeii.

So who exactly is Trimalchio? And why the enduring fascination with the 50 one-page-long chapters in which he features?

Trimalchio is an extraordinarily vain, fatuous, fat, not to mention flatulent (yes, really), arrogant, ignorant, and, above all, rich freedman who flaunts his wealth and the knowledge he doesn’t have… at every opportunity.

The classic images we have of Roman excess, vulgarity and gluttony are all personified in this gouty and incontinent buffoon whose excessive hospitality proves too much even for the greedy and opportunistic Encolpius, Ascyltus and Giton.

Course after course of increasingly sickening delicacies are wheeled out, often disguised as other things (e.g. pork cut into the shape of a bird), whilst the host conducts endless melodramatic cabaret acts involving staged errors committed by slaves who are then magnanimously absolved or freed.

Throughout the pretentious ostentation, Encolpius, as well as other guests, show their own snobbery and avarice by constantly criticizing and insulting Trimalchio sotto voce and then pealing into laughter or thundering into applause at their host’s feeble puns, misquotations and garrulous stupidity.

These wonderful passages are also peppered with interesting, amusing or macabre stories told by the dinner guests – one of which is the earliest known account of the werewolf myth.

The protagonists are only allowed to resume their immoral wanderings when they slip away during Trimalchio’s mock funeral, which he instigates in order to hear some flattering eulogizing.

Petronius’ brilliance here is seconded only to his bravery.

The character of Trimalchio was not merely a reflection of the nouveau riche former slaves with much, much more money than taste or education, but he is widely thought to have been a parody of no less a man than the Emperor Nero himself.

Indeed, the entire book can be read as an attack on the rapid moral and intellectual decline Rome suffered during the age of the said Emperor. After all, Nero’s reign was only 50 years after the Golden Age of Latin Literature, an age the author wistfully alludes to throughout the Satyricon.

It is perhaps because of this courageously damning and hilarious lampoon of the great dictator that the passages involving Trimalchio have endured so completely.

Unfortunately for lovers of art and freedom, Petronius’ bravery, belligerence and belittling finally caught up with him. He was arrested at Cumae in 66 AD, though in the end he opted for a noble suicide rather than succumbing to the whims of the authorities.

This too he did with the panache one would expect from such a flamboyant and sybaritic creature. Petronius’ job at court had been elegantine arbiter, the Emperor’s fashion adviser… so who can deny that he knew a thing or two about going out in style!

The words of Tacitus chronicle his last moments beautifully:

“Having made an incision in his veins and then, according to his humour, bound them up, he again opened them, while he conversed with his friends… he listened to them as they repeated, not thoughts on the immortality of the soul or on the theories of philosophers, but light poetry and playful verse… he gave liberal presents… indulged himself in sleep… even in his will he did not… flatter Nero… on the contrary, he described fully the prince’s shameful excesses… and sent the account under seal to Nero.”

![]()

![]()

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.