By Ryan Stone, Contributing writer, Ancient Origins

“A gentleman and a scholar.” There are few such men who fit this description from the “archaeological” community of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There were certainly gentlemen and scholars, yet those who understood the rules and propriety of historical investigations and those who studied the histories themselves were not always one and the same.

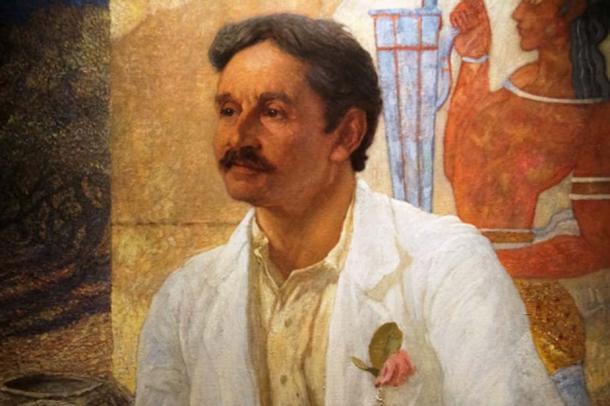

Enter Sir Arthur John Evans: Oxford graduate, philologist, excavator and Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum. Today he is best known for his contributions to pre-Classical Aegean archaeology through his discovery of the Minoans. Yet how this man came to discover an untouched society, what and who inspired him, and—most importantly—which of his postulations were accurate and which false are as important to the examination of his research as the discovery itself.

The Ancient Cretean Archaeologists

Sir Arthur Evans’ predisposition for classical era research and Homeric literature was furthered by the “revolutionary” efforts of Heinrich Schliemann at Troy in the late 19th century. Though now scholars have determined that Schliemann’s success at Troy damaged more than it salvaged, archaeology was not yet a discipline when Schliemann’s efforts began. It was merely a hobby of the rich and elite—those who could afford trips to far off places, fancy devices for use in investigations, and the paychecks required by mercenary diggers and tour guides. His damages, however, are considered in part why archaeology developed into a proper scholarly practice.

Schliemann’s work at Troy and at Tiryns, where he “discovered” the Mycenaean civilization that he associated with the Trojan War, inspired Evans’ to turn away from his Italian, British and Balkan research, and toward the archaeology of the Aegean. However, Evans’ work is far more respected than Schliemann’s, due to his background—both in academics and political negotiations—and methodology.

Portrait of Sir Arthur Evans by William Richmond, 1907 (Ashmolean Museum)

The Ashmolean Minoan Collector

Evans’ was well versed in art, history and philology, having made a name for himself as the author of many scholarly articles before he was entrusted as Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum—a job he would not have been hired for lightly. Under the employ of the Ashmolean Museum, Evans’ Aegean investigations began while attempting to transfer private collections of ancient artifacts (i.e. the Fortnum collection) to the Ashmolean.

It was under Evans’ advisement that the museum as a whole transitioned into one focused on art and archaeology, and began the assemblage of what would become the greatest Minoan collection outside of Crete. The success of this transition and the untimely death of Evans’ wife led to a shift in Evans’ interests, this time away from the museum and towards physical excavation.

In a moment of great insight during a visit to the island, Evans’ purchased the land where he would uncover the palace complex at Knossos. Within three years he had achieved a great deal, exposing Minoan frescoes, writing and numerous rooms within the complex.

Conversely, it was his future attempt at reconstructions of an unknown civilization, with a to-this-day untranslatable language, that is of concern.

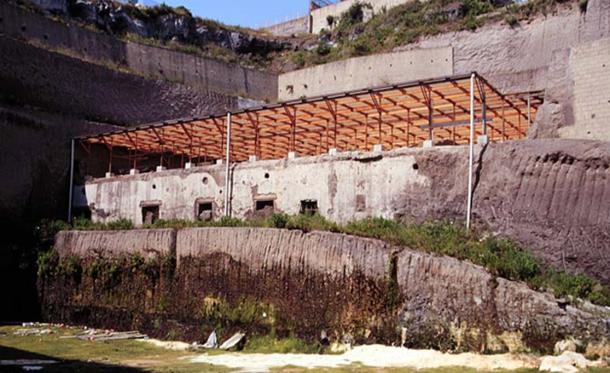

The palace complex ruins at Knossos

Evans’ Blurred Vision for Reconstruction of Knossos

Much like the man himself, the reconstruction Evans directed at Knossos could be described as short-sighted. In reconstructing his belief of what the complex at Knossos looked like in the Bronze Age, Evans inadvertently caused some damage like Schliemann did at Troy, though his intentions were for academic preservation and thus, he did not use dynamite.

At the time of his reconstruction (c. 1922), the name “Minoan” was borrowed from the Greek myth of King Minos and the Minotaur, and the various levels of construction were not accurately defined. (Such was the problem with Schliemann: his dynamite blasted through layers of Trojan culture before discovering that which has been determined as contemporary with Homer’s.)

A simple example of Evans’ miscalculation is his creation of the red, Minoan columns. There is no evidence that dark red columns—themselves constructed out of 20th century materials rather than what would have been used in the Bronze Age—looked as Evans depicted them. These Minoan columns were based on Greek models (despite the fact that the Greeks themselves borrowed the idea from older cultures), mounted on bases with capitals that resemble the Greek Doric style. Yet the Minoans likely had columns made from tree trunks, uprooted from the ground and flipped on their heads so the bottom of the tree held up the roof while the top of the tree served as the base.

Often criticized reconstructed red ‘Minoan’ columns at Palace of Knossos

Another concern of scholars is the restoration efforts of Evans and his team on the frescoes in the various “rooms” of the complex: the Throne Room, bathing room, etc. Though the color choices are believed to be relatively accurate based on comparisons with contemporary cultures and the natural ingredients in the area, the exactness of the frescoes is questioned. Scholars argue most fervently that Evans’ likely supplanted a “template” found intact at one wall to others as well, thereby incorrectly restoring the frescoes and injuring whatever symbolism had been intended by the original fresco and its location within the palace. (For example, the Tomb of the Diver in Paestum is believed to depict a diver as a metaphor for the transition from life to death. If the frescoes had a similar meaning in their particular locations at Knossos, that meaning has been covered by Evans’ restorations.)

Throne room at Knossos with restored/reproduced frescoes

Evans’ Discoveries

Yet we do not wish to discount the strides Evans did contribute to understanding the culture known as the Minoans. One of the best iterations of his successes lies in his theory of bull-worship. This hypothesis was based on the numerous depictions of bull-leaping and prominent displays of the “Horns of Consecration” (also named by Evans).

Both before and during his tenure on Crete, Evans investigated the significance of the bull alongside images of a double-axe, the mystery of each leading him from Oxford to Crete in search of their original cultures in the first place. (In fact it is believed that finding the double-axe on Knossos convinced Evans that the site was worth purchasing and exploring.) Evans continued his investigations throughout his time on Crete, and he is credited with the preliminary understanding of what is believed to be Minoan religion.

Restored building and frescoes at Knossos

Furthermore, Evans’ examination of bull-leaping frescoes led to the first somewhat defined chronology of the Minoans. Evans’ research of the frescoes insofar as dating, depictions, etc. led to the breakdown of the Minoan era into smaller periods similar to the Egyptian kingdoms—rather than Old, Middle and New.

The Minoan timeline is broken into Early, Middle and Late, and then further fragmented from there. Recent scholars such as John Younger have determined Evans’ religious assumptions and his chronological estimation of the practice of bull-leaping were both relatively accurate, and it is these initial parameters that allowed research into the Minoan period to propel forward rather than stagger.

Bull leaping, fresco from the Great Palace at Knossos, Crete, Heraklion Archaeological Museum

Despite the questionability of early archaeological methods—if the practice can be called such under Evans and Schliemann—the discoveries of the early 20th century began investigations of what would become some of the most fascinating ancient mysteries. Though more is still unknown than known of the Minoan culture—including what they might have called themselves—without Evans’ shrewd work at the Ashmolean Museum, and his extensive academic background at Oxford, he might not have discovered the complex at Knossos. He might have been just another rich history fanatic, waving around Homer’s works while placing dynamite in strategically destructive places.

Schliemann was successful in such efforts, but there is no guarantee Evans would have been too. Without Evans’ foresight and determined attempts to understand the pre-Mycenaean civilization, an understanding of the culture—assuming it was still discovered—might have been set back decades.

Bibliography

Chaniotis, Angelos. 1999. From Minoans farmers to Roman traders: sidelights on the economy of ancient Crete . Stuttgart: Steiner.

Davis, Jack L., Vasiliki Florou, and Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan . 2015. Carl W. Blegen: Personal and Archaeological Narratives. ISD LLC.

Evans, Arthur John. 1914. “The ‘Tomb of the Double Axes’ and the Associated Group and the Pillar Rooms and Ritual Vessels of the ‘Little Palace’ at Knossos.” Archaeologia. 65.1. pp.1-94. Accessed July 27, 2017.

https://digi.ub.uni-eidelberg.de/diglit/evans1914/0021?sid=4d5171c9f3498b7399864c2eb2aac0e8

Hamilakis, Yannis. (ed.) 2002. Labyrinth Revisited: Rethinking ‘Minoan’ Archaeology. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

MacEnroe, John. 1995. “Sir Arthur Evans and Edwardian Archaeology.” The Classical Bulletin . 71.1. pp. 3-18.

MacGillivray, Joseph Alexander. 2000. Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology f the Minoan Myth. New York: Hill and Wang.

Rubalcaba, Jill and Eric Cline. 2011. Digging for Troy: From Homer to Hisarlik . Charlesworth.

Stokes, Lauren. “Trojan wars and tourism: a lecture by C. Brian Rose”. Swarthmore College Daily Gazette. Accessed July 29, 2017.