Plotinus: Founder Of Neo-Platonism

Written by Ed Whalen, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The pre-Socratic Atomists were a group of ancient thinkers who proposed a materialistic theory of the cosmos. Among the first to propose a mechanistic view of the universe, the Atomists argued that the world was composed of atoms. Their work was crucial in the development of ancient philosophy and modern science.

The Origins of pre-Socratic Atomists

Parmenides of Elea was a pre-Socratic philosopher from what is now Southern Italy. Possibly the first monist (monism posits that all things derive from oneness), Parmenides argued everything was part of a single, unchanging mass. His denial of change greatly influenced the first Atomists.

Leucippus is regarded as the first true Atomist. Living in 5th century BC, Leucippus was likely born in Miletus, which is located in modern-day Turkey, and later moved to Abdera, a wealthy Greek city on the Thracian coast. Many, including Aristotle, claimed the Leucippus was the most important Atomist.

Democritus was born in the city of Abdera in about 470 BC into a wealthy family. He was very well travelled, and may even have even visited Babylon. When Democritus returned to the Greek settlement in Thrace, he conducted numerous scientific experiments and wrote several works on the theory of atoms.

Democritus was a polymath and in ancient sources was portrayed as the ‘laughing philosopher’ because he was always mocking the stupidity of his fellow citizens. Despite this, he was hugely respected in his home city and is credited with the founding of the influential School of Abdera.

The Theory of Atomism

The pre-Socratic Atomists, especially Democritus, held that the world was made of atoms — defined as the smallest elements in the universe. Atoms had several characteristics: they were invisible to the naked eye, indivisible and eternal. It was believed that atoms could come together and form complex structures, making them the building blocks of the entire world.

For the Atomists, the world consisted of matter which followed specific patterns and laws. Democritus argued that the atoms moved in a void and that all change was a result of them coming together and breaking apart. There were a variety of different atoms that explained the variety and dynamism observed in the natural world. Atoms thus explained natural events and phenomenon. Democritus and his followers believed that the world came about as a result of a collision of atoms.

For the Atomists, there were only naturalistic explanations of reality. This has been likened to 19th-century scientific ideas about the world, and for this reason many see the atomists as the forerunners of modern science. The Atomists were very interested in observing nature and may have developed early scientific theories. For instance, Democritus developed the theory of epistemology, which held that all knowledge derived from sensory experiences. In this way, he can be regarded as a forerunner of the empiricists.

For Democritus, the faculty of reason existed to interpret sensory data, creating true knowledge of the world. Interestingly, the philosopher also believed that humans had a soul, but that this too was made out of atoms. He held that many cultural institutions were the result only of our mental cognitions and had no basis in reality. As a result, cultural institutions and beliefs could be changed for the benefit of humanity. Because of this, many scholars have seen Democritus and members of his school as early humanists. Indeed, Democritus and his followers believed that the ancient gods were a human invention.

The Atomists believed that humans originally lived like animals but developed societies and technology in order to survive. Sadly, there is much we do not know about the pre-Socratic philosophers, as nearly all their works have been lost.

The Influence of Atomism

The pre-Socratic Atomists had a huge influence on later philosophy, especially in the Classical World. Aristotle was very familiar with the works of Democritus, but he opposed the Atomists. However, the School of Abdera influenced the Epicureans, who held that only rational pleasure was the only virtue. Their materialism and metaphysics are based on Atomist teachings.

Many Christian scholars believed that Democritus and his followers were atheists. Historians believe that the School of Abdera contributed to the widespread doubts among the elite and intellectuals about the existence of the gods.

The Atomists also appear to have influenced the Sophists. The great Sophist Protagoras came from Abdera and his relativist philosophy was possibly based on Democritus’ epistemology. Another school influenced by the Atomists were the Sceptics. Anaxarchus, another citizen of Abdera, was a philosopher who accompanied Alexander the Great on his conquests. Anaxarchus’ unique interpretation of Atomism led him to doubt the reliability of knowledge. This is regarded as an important influence on Pyrrhonism and its teachings of philosophical skepticism. During the 17th century in Europe, many scientists were inspired by the Atomists and revived their teachings.

Conclusion

The pre-Socratic Atomists were revolutionary thinkers. Among the first in history to propose a materialistic and mechanistic theory of the universe, their theory of atoms promoted a scientific and rational view of the world. Many feared them, but they were very influential. They not only inspired later philosophers such as the Epicureans, but they may also have laid the foundation for modern science.

References:

Russell, Bertrand (1987). History of Western Philosophy. London: Routledge.

By David Hooker, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

As I read and re-read the philosophers, tragedians, poets, and other commentators of the ancient world, I am constantly amazed. The insights they came up with regarding natural and speculative philosophy, nature (and human nature), and the universe oftentimes drop my jaw! More than anything else, it’s stunning how close they were to our modern understanding of physics, the universe, and much of the knowledge we take for granted in the “settled” scientific world we live in today.

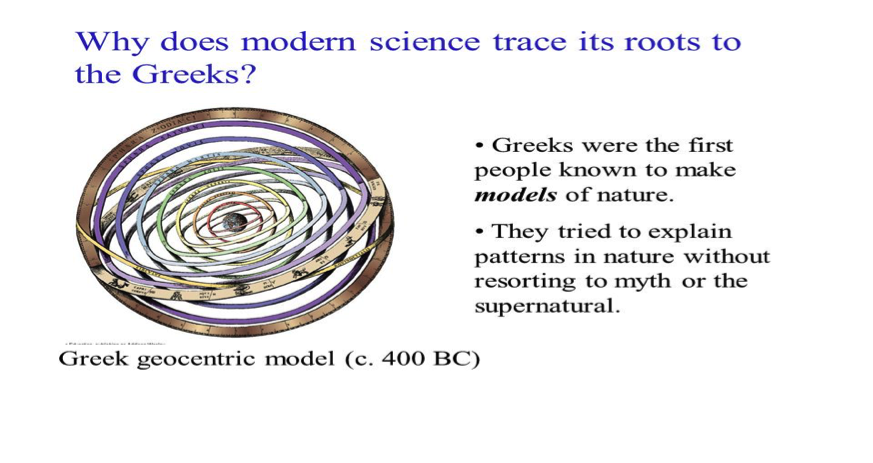

It was the pre-Socratic philosophers (Thales, Anaxagoras, Parmenides, Pythagoras, Heraclitus, Empedocles, et.al.), however, that really set the stage for all of the great, critical philosophy to come. I like to call their era the “Big Bang” of Western philosophy, as these guys were really “on to something.”

The Philosopher’s Mosaic, villa at Torre Annunziata near Pompeii

They didn’t possess all the wonderful scientific tools we have today (the electron microscope, the Hubble Space Telescope, etc.) to better understand nature and our universe, but they, by mere reasoning and daring to ask critical questions, came up with astonishing insights. Here is a brief overview of three pre-Socratic philosophers you’ve likely never heard of, who, nevertheless, were really “on to something”.

Hermotimus of Clazomenae

Hermotimus (ca. 6th Century BC) was a member of the Ionian League and hailed from near Smyrna (modern Izmir) on the west central coast of what is today Turkey. Unfortunately, like many of the more obscure pre-Socratics, none of his original works is extant. As such, we rely on mentions by other philosophers and writers, such as Aristotle, to provide us with information about their thinking.

Hermotimus is credited with being the first philosopher to propose the stunning idea that mind is fundamental in the cause of things. He submitted that physical entities are static, while reason causes change. This sounds remarkably similar to one of the critical axioms of modern day quantum mechanics: that the human mind is an active player in “creating” the reality we perceive.

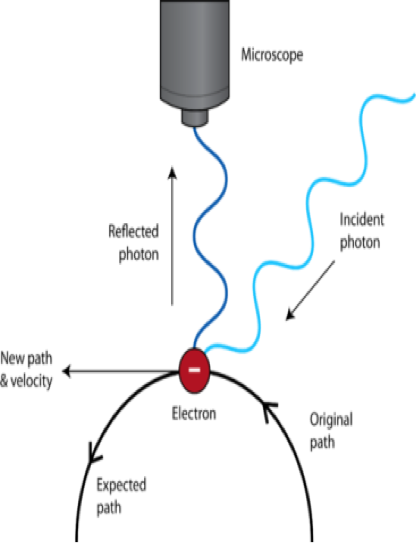

For instance, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle states that it is impossible to know simultaneously the exact position and momentum of a particle. That is, the more exactly the position is determined – from human perspective – the less known the momentum, and vice versa. Wrap your mind around that, dear reader! At the quantum level, nature is always in flux and unpredictable; chaotic in a sense. By observation and participation, we humans stamp our sense of “order” onto it, and it is thus a random universe to which we bring meaning.

The Uncertainty Principle

Sextus Empiricus, a 2nd century AD philosopher and physician, places Hermotimus with Hesiod, Parmenides, and Empedocles as belonging to the class of philosophers who held a dualistic theory, that of a material and an active principle (reason) together being the origin of the universe (cf. Aristotle’s “Unmoved Mover”). While I don’t believe Hermotimus had anything like quantum mechanics in mind (he was likely presaging Aristotle’s “Unmoved Mover” in cosmology – a Creator, or First Cause in creation), he was definitely “on to something.”

Alcmeon of Croton

Born in 510 BC, Alcmeon was a contemporary of Empedocles and Anaxagoras. While none of his works is extant, we have comments from Aristotle and Theophrastus to enlighten us. Alcmeon was considered a brilliant physician of his day and lived during a transitional period in Greek medicine. While traditionally medicine was wed to philosophy and religion, it took a dramatic turn in the sixth century BC.

Alcmeon was a pioneer in the strictly empirical method of diagnosis, as opposed to the more “generalist” approach of his predecessors, who attributed a disease or problem to some transgression against a god. Instead, Alcmeon looked at the individual and wanted identifiable facts: how do the senses function in the case? Why does the patient present as so? What are the symptoms actually telling us?

He introduced his doctrine of physical equilibrium (isonomia) to define and explain the state of health in the patient. Alcmeon performed detailed physiological investigations of the different senses in order to explore the actual causes of the sensations and symptoms presented. Moreover, he thought that the human body should be “in balance” in a healthy person. Four aspects, or “powers,” of cold, hot, wet, and dry should naturally be in balance in the human body. If any of them gets out of whack, problems present. While primitive, this “four humors” pathology persisted well into the Middle Ages… And remember – physicians were blood-letting routinely as recently as two centuries ago!

The important thing is that Alcmeon set the stage for future physicians with the focus on the patient’s sense information and how he/she presented. What did those symptoms say? His efforts to focus on empirical data, with a mind to keep the patient in equilibrium, were seminal in the advance of the medicine of his era. Alcmeon was definitely “on to something.”

Diogenes of Apollonia

Diogenes of Apollonia, born 460 BC, is often considered the last of the pre-Socratics and seems to have done most of his important work in Athens. He was influenced by Anaxagoras’ doctrine of Mind, and was indebted to the atomists’ view that coming to be and passing away were caused by the mixing or separating of elements of the same kind. Following Anaximenes, he proposed the physical theory that all things in the world are modifications (heteroioseis) of the same basic stuff: Air.

The assertion that everything in the universe is a modification of a single basic substance was made by Diogenes on the force of two related considerations: 1.) physical interaction would be impossible if each individual thing were radically and substantially different from everything else, and 2.) the uniformly exhibited harmony of nature would be a mystery if an underlying, all-pervasive intelligence did not control and guide everything. To deny these considerations would be equivalent, Diogenes thought, to ignoring the ways in which things mix, or help or harm each other, as well as the way things depend on each other (as in water to a plant, or any living thing breathing air). It would be tantamount to overlooking the balance, measure, and intelligible structure that characterize every aspect of nature.

Diogenes asserted that air is the basic cosmic substance, since it is the life principle and intelligence of the whole animate world. In his thought, air is the source and guiding power of every physical change. It is the most versatile and adaptable substance. Its capacity to manifest itself in a wide variety of forms, and under every conceivable condition – hot, cold, wet (humidity, vapor), and dry – is evidence of its rationality and divinity. To the extent that there is air in all animation, a part of God is in every living creature.

While we moderns don’t share the ancient notion that “earth, air, fire, and water” comprise the basic cosmic substances (we have a catalogue of 118 elements that comprise nature, as of 2017) there’s no question that Diogenes was “on to something.” Diogenes, in his time, was working in a period of transition in Greek thought. He attempted to reconcile ancient insights with new discoveries and bring pre-Socratic speculations inline with the systematic details of biological and natural observation.

The late, great cosmologist and astrophysicist Carl Sagan was very impressed by the ancient Greek thinkers. (Dear reader: if you haven’t read any of Dr. Sagan’s great books or seen his “Cosmos” series on DVD, what are you waiting for?!) He speculated that had they been allowed to continue to flourish, we as a human species would have become a space faring civilization centuries before the modern era. Think of that, my friends! And the bedrock of their scientific and philosophical ideas and speculations was formed by the pre-Socratics. Most certainly, they were “on to something.”

By David Hooker, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Who hasn’t looked up into a sky full of stars and wondered what our place is in this vast universe? What is the nature of this environment we find ourselves living in? Are there underlying substances to this “stuff” that makes up our world? For the contemplative among us, there are all too often few satisfying answers, yet an endless list of questions. This is especially true for those of us who have cruised around our sun on planet Earth for many years, as when we were younger we seemed to “know” everything! A revered professor of mine once said that as we progress in age, that is precisely the trajectory: as we go along, the “answers” become fewer and the questions accumulate, until we have pretty much nothing but questions! Perhaps that is a bit cynical, but not far off the mark in my opinion.

Empedocles, an ancient Greek philosopher, was one such man who contemplated these essential questions. Born in Acragas (now Agrigento), Sicily, sometime during the early 5th century B.C., and dying in 444 B.C., he belongs to a remarkable group of philosophers we call the pre-Socratics. Among this group are many incredible thinkers such as Thales of Miletus (with whom is normally reckoned the beginning of this era; born in 624 B.C.), Anaximander, Anaxagoras, Protagoras, Heraclitus, and the list goes on up until Socrates (born 470 B.C.).

I liken this period to the “Big Bang” of Western philosophy, since so many of the questions that have occupied the philosophic enterprise from that day until now were articulated, pondered, debated, and written about during those nearly two remarkable centuries before Socrates. The role of the senses in knowledge, the nature of reason, morality, religion, the gods, the soul, and what kind of stuff the universe was created of, are just some examples. The questions asked then, as well the methodologies and schools of thought that developed in order to answer them, have persisted to this day (with variations of course).

What we today call “Greece” was then a far flung set of city-states and islands throughout the Mediterranean, modern (western) Turkey, the Aegean Sea, etc. This was a time when these various geographic locations were the hubs of trade routes, aiding the transportation not only of goods but of a plethora of cultural, religious, political, and philosophical ideas.

What is This Thing Called Nature?

Empedocles was a poet, and his only surviving major works (in fragments and written in hexameter) are On Nature (Peri Phuseos) and Purifications (his later religious-themed work). Being that I could write all day about Empedocles and the implications of his thought (and you likely have other Classical Wisdom Weekly articles to attend to, don’t you, dear reader?), I will attempt instead to give a brief overview of On Nature.

For many of the pre-Socratics, their approach to philosophy consisted of trying to get at the root of things, beginning with the universe at large and then moving inwards from there. Empedocles posited four underlying substances, or “elements” comprising nature (phusis): Earth, Air, Fire, and Water. These he considered to be the “roots” of the “stuff” which we perceive and interact with every day. This view of nature remained prevalent in western thought down to the Renaissance. (It still survives today in some circles, especially in neo-Pagan thought.)

Of course, today we generally have a far different understanding of the word “elements,” or the underlying “stuff” of the natural universe. Our modern understanding of “all that is” (for Materialists, anyway) comes down to the 118 elements (as of 2017) arranged on the periodic table. (Catalogued in this fashion beginning with Mendeleev in 1869.) The air that we breathe, for instance, is comprised of several gases, primarily nitrogen (78%), oxygen (nearly 21 %), and argon (nearly 1%), along with other trace elements.

As the entire philosophic enterprise is often referred to as a millennia-long “conversation,” individual philosophers, such as Empedocles, are often seen as in conversation with, or as reacting to, other thinkers of their time (or immediately preceding). From Parmenides, Empedocles accepted the fundamental principle “that nothing can arise out of nothing,” nor can anything perish into nonentity. Sound familiar?! (“Matter is neither created nor destroyed” – 18th Century French chemist, Antoine Lavoisier) Whereas for Parmenides this meant that all motion and change must be illusory, Empedocles admits that there is a real process in nature: “the mixture and separation of things mixed.”

Since the elements are four (rather than a monistic “One”), Empedocles then is able to explain natural change as the result of the combination, separation, and regrouping of these indestructible entities. Moreover, in Empedocles’ thought, these four interact continually under the influence of two cosmic powers on the other: Love and Strife. These two function as forces of attraction and repulsion. The power of Love, for instance, functions first by bringing together “like” together with “like,” (earth to earth, fire to fire, e.g.), but also assimilates the four elements one to another, creating a homogeneous compound of organic unity.

Strife, on the other hand, is seen as a force of differentiation and repulsion for the elements, one that creates great diversity in nature. This is really what we mean by the statement that the Universe (humanity as well) is “dynamic” (think plate tectonics, volcanism, impact events, etc.) – nature seems to be both “fixed” in the sense that matter is neither created nor destroyed, yet always in flux by forces molding and shaping the reality we perceive. It is not that the universe itself undergoes any fundamental change, but that the forces of Love and Strife, with their constant bringing-together and forcing-apart, create what we see as “change” over time. Here is a chart roughly depicting Empedocles’ view:

What is This Thing Called Love?

Sometimes charts just don’t quite cut it. If you asked me to show you what love is, dear reader, you would likely be disappointed if I returned with a chart like the one above. Thus, along with the chart I have decided to appeal to this great song from the popular American music composer Cole Porter, because I believe it will further aid us in envisioning exactly how Empedocles conceived of the universe.

Cole Porter penned many songs that have been adapted by jazz musicians over the past nearly one hundred years, with “What is this Thing Called Love” being one of the most popular (it now belongs to the pantheon of classic tunes from the “Great American Songbook” that Jazz musicians love to play and improvise over). Jazz musicians love to rearrange the chord structures of popular songs (called “substitutions” – often thought to be “hipper” and more accommodative to improvisation on instruments such as saxophone, trumpet, piano, bass, et.al.). They also love to change the underlying rhythm (resetting it to Latin rhythms, swing feel, ballads, etc.) and tempos (faster or slower). It is a real art to do this in a way that both pleases the players and the audience, and to come up with something “new” and relevant to the occasion.

As I continued to think about Empedocles, it occurred to me that the jazz musicians’ art could serve as an analogy to Empedocles’ understanding of Love and Strife. Though western music utilizes 12 different tones (in a chromatic scale), it’s all in how they are juxtaposed that makes something “new” out of the underlying, unchanging substances, or notes (a new melody, new set of chord changes, rhythms, etc.) of music. As is the case with Love and Strife, acting on the four primal Elements in various ways, the 12 different tones are constantly being brought together and forced apart in various ways by musicians, while, like the products of Love and Strife, beings still dependent on what underlies them. As Empedocles put it,

Now there grows to be one thing alone out of many; now again many things

separate out of one.

Hopefully you have found this analogy helpful in understanding the way Empedocles viewed the universe. Music, like Nature, has shown itself to be a constant source of new creations. This is no surprise, as music is a product of Nature’s many creations. For Empedocles, it is the forces of Love and Strife that make the universe so dynamic. As a result, life is dynamic, and it is this very dynamism that makes it so joyful to contemplate. Empedocles, along with his fellow pre-Socratics, set Western philosophy on a journey of contemplating the cosmos. Friends: we are most fortunate to be able to continue their enterprise. Let us not take it for granted.

By Jacob Bell, Associate Editor, Classical Wisdom

Most folks know something about atomic theory… its surprising ancient history, however, is often less discussed.

The current modern atomic theory is the prevailing scientific theory of matter and explains the physical world in terms of discrete units referred to as atoms. Atoms are made up of various subatomic particles such as electrons, protons, and neutrons.

However, the term “atom” actually comes from the Greek adjective atomos, which means “indivisible.” Like many other modern scientific and philosophical theories, atomic theory has its roots in ancient Greek philosophy.

Leucippus, living in the 5th century BCE, was the founder of atomism. This early account of atomic theory arose in response to Parmenides’ denial of the void. Leucippus claimed that without the void, motion was impossible. He also claimed that equating the void with nonexistence was a false equation.

Leucippus argued that the void existed as empty space and he used this as a foundational assumption in his atomic theory. He went on to expand this notion by insisting that the world was made up of one type of substance, namely atoms.

Leucippus went on to claim that this fundamental substance was infinite in number, indivisible, moved through empty space, and came together in particular combinations which gave rise to the visible objects of the world.

We don’t know much more about this first encounter with atomic theory because we don’t know very much about Leucippus and only have a few surviving fragments of his work.

Fortunately, much more is known about Democritus, who was a prolific writer and student of Leucippus. Democritus lived from 460-370 BCE.

Democritus elaborated on the theory of atoms, could predict weather changes, and dissected various animals throughout his career as a natural philosopher.

Intent on finding wisdom, he spent his entire inheritance traveling and studying. During his travels he visited Egypt, Ethiopia, Persia, and India. When his money ran out, he returned home to Abdera, where his brother took him in.

Democritus was given two rather interesting nicknames: “The Laughing Philosopher,” and “The Mocker.”

His fellow citizens gave him such titles because he would routinely make public appearances in which he mocked, condemned, and laughed about the foolishness and silliness of human affairs.

Despite being given such seemingly unprofessional nicknames, Democritus became well-known for his knowledge of the physical world. He wanted to explain the world in natural terms and without reference to dogmatic mysticism.

In his expansion of atomic theory, he maintained the indivisibility of the atom because he claimed that it would be impossible to divide matter ad infinitum. He argued that each atom has a density that was in proportion to its volume, and he claimed that the void (empty space) was eternal in its existence.

Atoms, for Democritus, are too small for the naked eye to see. They float around the void, consisting of various shapes, and collide into one another.

Maintaining the notion that every physical object is made up of the same stuff, Democritus believed that a type of image must emerge from the combination of atoms which give rise to external objects. This image causes an impression upon our senses, which results in the appearance of the object in question.

Not only is our vision caused by a combination of atoms resulting in the appearance of a physical object, but all of our sensations are the result of atomic combinations. For instance, Democritus claimed that the taste of bitterness is caused by small, angular, and jagged atoms passing over the tongue. In contrast, the taste of sweetness is caused by larger-smoother atoms.

Perhaps most radically, Democritus claimed that the only things that can be said to truly exist are atoms and the void. Everything else that is thought to exist is simply a matter of social convention.

Democritus went on to claim that sensations such as the feeling of hot or cold had no real existence and were simply produced in organisms through a particular combination of atoms moving through the void.

Because we can perceive only the physical conglomeration of atoms that results in a visible physical object or subjective sensation, Democritus claimed that we were incapable of fully understanding the cosmos. There would always be something of which we could not observe, deduce, or understand due to this indirect experience of atoms and the void.

These early conceptions of atomic theory predate our modern theory of the atom by more than 2,000 years. It wasn’t until the 19th century that chemists began to refer to particular irreducible elements as atoms.

The 21st century notion of what an atom consists of is vastly different than that of the ancient Greeks, but that doesn’t diminish what many would claim is a kind of genius that went into developing such a theory.

Leucippus and Democritus were intuitive and wise beyond their years. Like many other Greek philosophers, they looked past tradition and cultural convention, forging their own path and establishing their own worldview. Idyllic in their innovative nature, they remain a great source of inspiration to this very day.

By Jacob Bell, Associate Editor, Classical Wisdom

“Man is the measure of all things…”

It is likely that you have heard this phrase uttered at one time or the other. It is an explicit declaration of relativism, and one of the earliest accounts of such a theory.

It was Protagoras who made this statement. He lived during the 5th century BCE and was part of the older Sophists, which included Gorgias, Hippias, and Prodicus.

The Sophists were traveling instructors who had expert knowledge regarding the art of rhetoric and persuasion. They understood the importance of appealing to the emotions as opposed to trying to convince someone of something through the use of pure logic and reason.

Because of their emphasis on evoking emotions and igniting passions, the Sophists are often interpreted as immoral charlatans rather than real philosophers. Regular readers may remember my Sophistry article regarding profit and selfish-gain…

Today I wish to approach the Sophists as true philosophers who were capable of great insights.

The idea that “man is the measure of all things” is essential to understanding the Sophists. One can interpret such a statement through the lens of crude relativism, which seems to be the most common interpretation.

It is also, in my opinion, a false and indignant interpretation.

Crude relativism would claim that all of our notions of justice, morality, knowledge, virtue, wisdom, and ethics are a matter of what one thinks is just, or moral, or true, or virtuous. With this view, there is nothing from which we can determine a higher order truth – all truth stems from what a society or individual thinks or believes to be the case.

This position leads one to claim that relativism is ultimately a theory of self-refutation. If all truth is relative to a person or society and their beliefs, and no thesis is more valid than any other, then relativism cannot be a more true or valid theory, either.

A crude relativistic view destroys itself before it gets off the ground.

I think this is a poor way of interpreting Protagoras and relativism. It commits the strawman fallacy, which is to intentionally misrepresent an argument or statement in order to make it a weak position which can be easily defeated.

We can’t know exactly what Protagoras had in mind when he claimed that “man is the measure of all things,” because we don’t have much of his original writings. But I wish to steelman this statement and create a strong argument through a more sophisticated interpretation of relativism.

Essentially, relativism is the idea that what is good, bad, true, and false is relative to a particular framework. I don’t think this statement can be refuted. We were born, evolved, and grew out of this world. We always have a perspective and a framework from which we navigate the world.

We cannot separate ourselves from the world in order to view anything from an objective standpoint. This doesn’t mean, however, that all views are equally valid, and it definitely does not mean that any statement is just as true as any other.

Protagoras of Abdera, Painting by Ribera

Now, before you curse my existence and accuse me of being a charlatan, let me explain…

Let’s talk about board games for a moment. A board game is arbitrary in the sense that someone made up an entire framework from which to view and play the game. They created a story, rules for how to play, and an ultimate goal. It is all a fictional creation and a human construct. This does not mean, however, that all strategies for playing the game are equal, and one can certainly make truth statements regarding the rules and the best way to play the game.

We have similar human constructs and frameworks from which we view the world. These include values, motives, and goals. The values, motives, and goals in one culture may not be exactly the same as another culture, but that doesn’t mean we should just throw our hands in the air and declare everything equal.

We are still capable of making real truth statements about the world, and some strategies are better than others when we navigate the world in pursuit of certain goals. There also seems to be a wider-more-basic framework that has been embedded into most of mankind – probably through our shared evolutionary history.

There is also an important distinction that must be made between our personal-subjective experiences and the intersubjective world.

You can say the taste is subjective… but the nutritional value not… source

It is true that we all view the world from a particular framework, and it is true that we may see things differently from one another, but when I claim that it is cold outside, and you say that it is warm, we are projecting a relative value onto an intersubjective situation.

By intersubjective, I just mean a situation that is publicly accessible. We can both feel the air, experience the atmosphere, and talk about it. My personal-subjective experience of the intersubjective circumstance might be different than yours, but that isn’t what is important.

The importance is on the intersubjectivity of the situation and our ability to agree on particular aspects of the circumstance. We can both measure the temperature of the air, and we can agree that it is 60 degrees Fahrenheit outside – this is our intersubjective experience. I can then claim that it feels cold to me, and you can claim that it feels warm to you, this is our relative or personal-subjective experience of the intersubjective phenomena.

You might interpret the data differently, but the intersubjective data is presented to both of us equally.

Intersubjective Data: 60 degrees outside

My personal-subjective experience of the data: Cold

Your personal-subjective experience of the data: Warm

Am I right in claiming that it is cold? Or are you right in claiming that it is warm? I don’t think it even makes sense to ask or answer such a question, because we have moved from the intersubjective to the relative or personal-subjective.

The same reasoning can be applied to truth-statements about the world. If you claim that the earth is flat, and I claim that it is spherical, we aren’t obligated to believe that we are both right. The earth is part of our intersubjective world. We both have access to the earth in the same sense. You might not believe the evidence, but your belief doesn’t change the structure of the earth.

Protagoras provides us with the foundation for relativism. He was ahead of his time in positioning mankind away from absolutist types of thinking. Protagoras was a true philosopher, and not a mere rhetorician.

He recognized that we couldn’t be objective observers because we are always viewing things from a subjective framework. This was a radical truth for his time, but one that seems undeniable. Moreover, it opened a new way of thinking and reasoning about ourselves, the world, and our being-in-the-world.