The Ides of March

by Ed Whelan, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The 15th of March may just seem like just another day to the modern world. Yet in ancient Rome, the day was crucial. It was the date of the Ides of March, when several religious festivals were celebrated, and it went on to become infamous as the day that Julius Caesar was assassinated. Considering this, it’s perhaps natural that the day has become associated with ill-omens and bad luck in modern times.

The Ides of March

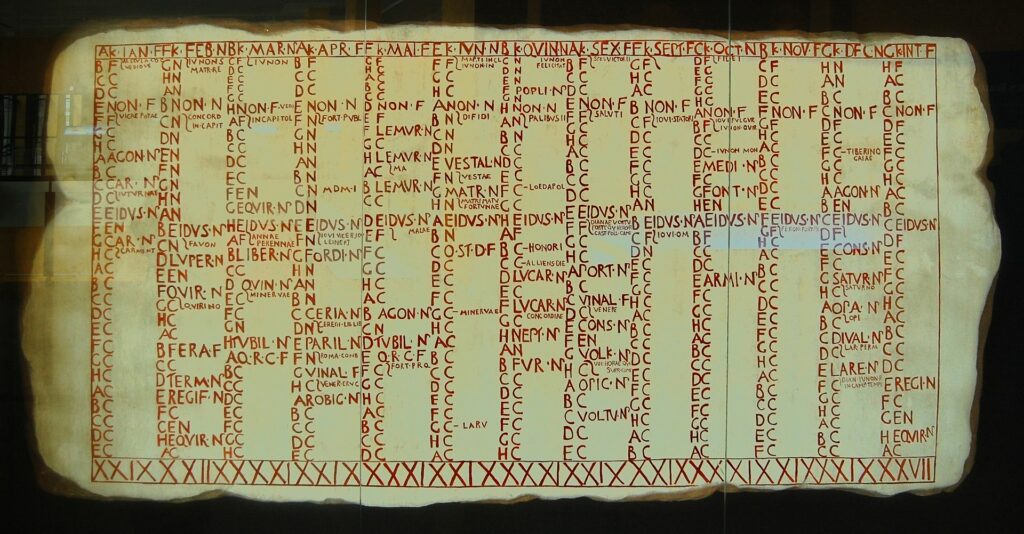

The Ides was a day that occurred every month in the Roman calendar, and fell either on the 13th or 15th day of our calendar. The date was determined by the full moon, and the Ides of March fell on the 15th. The Romans had a very unusual way of counting dates. The dates were calculated based on distance the from specific days: the Kalends, the Nones and the Ides. The Kalends were at the start of every month, and the Nones happened on day 5 or 7 of a month. An example of Roman dating is as follows: the 13th would have been known as two days before the Ides of March.

Religious Festival

The Ides were held to be sacred to Jupiter, the supreme deity in the Roman pantheon. It was also associated with the festival of Anna Perenna. This deity was the embodiment of the cycle of the year. Many historians believe that the day was once the New Year in Rome. The Anna Perenna festival was marked by feasting, drinking, games, and gladiatorial games.

Like many Roman carnivals, the Anna Perenna festival was a time when celebrants could subvert traditional power relations between social classes and gender roles; people were allowed to speak freely about sex and politics. The Ides of March was also the first day of a week-long celebration of the Anatolian Mother Goddess Cybele and her consort Attis.

Other sources state that the Ides of March was the day on which the Mamuralia was held. This was a day that saw an old man dressed in animal skins beaten. It is possible that this was related to some ancient scapegoating ceremony, or some forgotten New Year ceremony. As you can see, Roman religion was very dynamic; it evolved, especially during the Imperial era, when foreign customs and gods became popular. Yet as the Empire was Christianized, the Ides lost their religious significance.

The Assassination of Julius Caesar

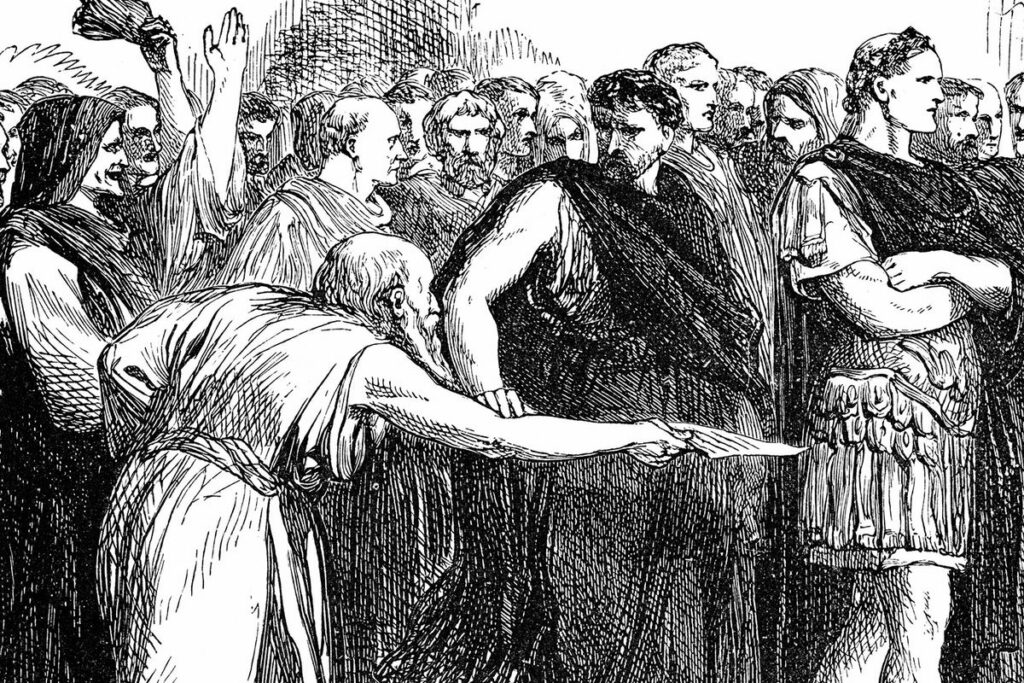

On the Ides of March one of the most infamous political assassinations of all time took place. Julius Caesar, one of history’s greatest generals and the dictator of Rome, was warned not to go to the Senate House, as his life was in danger. In many sources, he ignored the prophesy of a seer. As he took his seat in the Senate House, Caesar was attacked by up to 60 conspirators who wanted to restore the Republic. They stabbed him multiple times, and Caesar died before a statue of his great rival and enemy Pompey. The conspirators led by Brutus and Cassius may have selected the Ides of March because it was an auspicious day, and they knew that many poor people, who were sympathetic to Caesar, were outside the city at gladiatorial games. The assassination of the dictator set the stage for a civil war and the collapse of the Roman Republic.

Beware the Ides of March!

For many centuries the Ides of March has been seen as unlucky and even dangerous. In the ancient world, the day was not seen as inauspicious; people looked forward to it as a day of rituals and fun. Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar contains a memorable scene where a soothsayer tells the title character to ‘beware the Ides of March’. This line became very popular and is much quoted, and led to the belief that the Ides of March was unlucky. In modern popular culture, the Ides of March has become a by-word for ominous events and bad luck.

Conclusion

The Ides of March was a very important festival in the Roman calendar. It was associated with a number of religious festivals in the Roman Republic and Empire. The day was often marked by festivals and fun. It became notorious because it was the day when Julius Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC. The day has since become synonymous with misfortune in modern times, but was viewed as a day of celebration in the ancient world.

So, there is no reason to believe that the Ides of March are unluckier than any other day, after all!

References

Balsdon, John Percy Vyvian Dacre. “The Ides of March.” Historia: Zeitschrift fur Alte Geschichte (1958): 80-94.

Horsfall, N., 1974. The Ides of March: some new problems. Greece & Rome, 21(2), pp.191-199.