By Jocelyn Hitchcock, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

We all know the varsity team: Einstein, Newton, Pythagoras, Descartes. These names are drilled into our heads all through grade school math and history classes, and possibly accompanied by an under-the-breath curse from a disgruntled calculus or physics student. However, another mathematician should receive our attention: Euclid of Alexandria.

It is difficult to underscore enough the importance and significance of Euclid and his impact on mathematics for the subsequent 2000 years. Nonetheless, we will try.

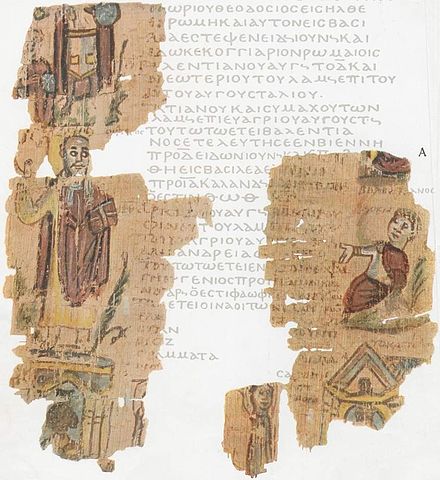

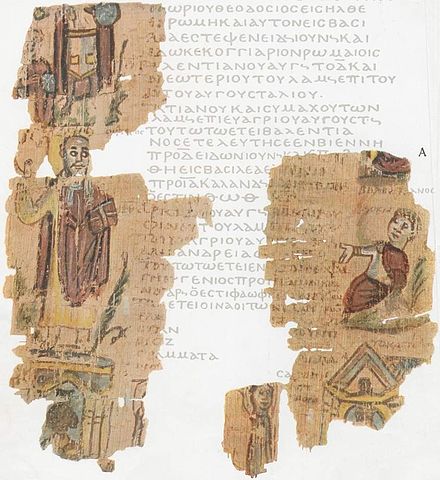

Euclid of Alexandria

Euclid’s Early Life

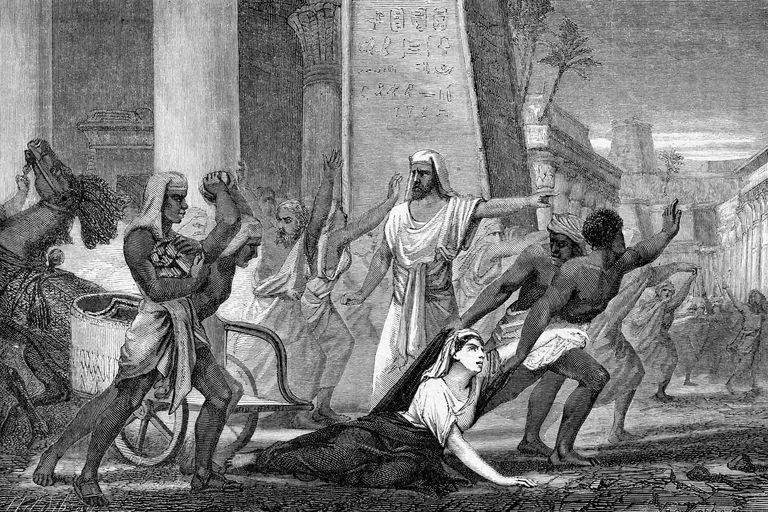

The documentation of Euclid’s life is scant, at best. While we have a great deal of his work in extant, facts about Euclid as a person come down to us mainly through little snippets by Proclus and Apollonius (among others). Proclus, a Greek philosopher living in the 5th century CE, writes retrospectively and so his information must be taken with a grain of salt. He writes that Euclid taught in Alexandria, Egypt during the time of Ptolemy I Soter (4th-3rd century BCE). This places him as younger than Plato, but slightly older than Archimedes. Euclid was likely born around 300 BCE and resided in Alexandria, Egypt for most, if not all, of his life. Some historians think that he might have studied for a bit at Plato’s Academy in Athens, but this is conjecture based on his style of teaching. Past this, nothing is known of Euclid.

Map Showing Alexandria, Egypt, birthplace of Euclid

Euclid’s Career

Often called the “Father of Geometry,” Euclid was a teacher of mathematics, cultivating a school of pupils not unlike the style of the Academy. Proclus writes that Ptolemy once asked Euclid if there was a “shortened way to study geometry than the Elements, to which Euclid replied that there was no royal road to geometry.” This would suggest that not only was Euclid noteworthy among mathematicians and scientists in Alexandria, but was prominent enough to have an audience with the ruler of Egypt. As with details of his early life, we don’t know specifics regarding his career, save for his extant works and the fact that he was a prominent teacher in Alexandria.

Euclid’s Works and Achievements

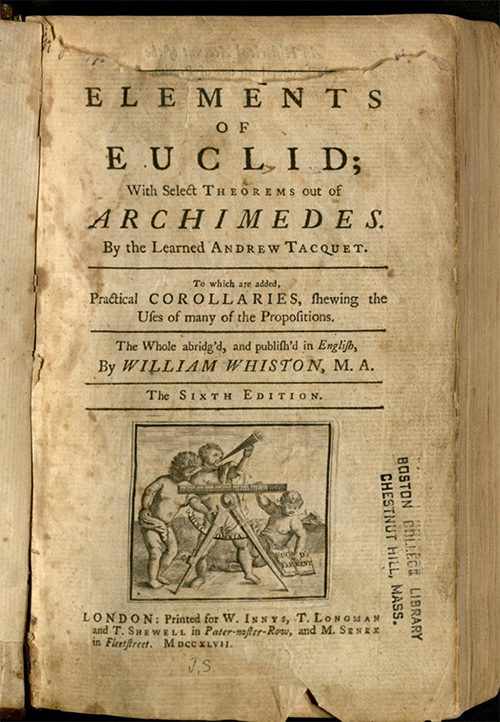

Euclid likely wouldn’t have reached his level of renown if his works didn’t survive to such an incredible extent. His main work, The Elements, is a proto-textbook of 13 sections pulling together definitions, theories, and constructions of mathematics at the time. He covers geometry, number theory, and incommensurate lines- all subjects that have proved to be invaluable over the development of mathematics.

The cover of Euclid’s Elements

The Elements consisted of five general axioms and five geometrical postulates. Euclid provided the basic model for mathematical argument that follows logical deductions from initial assumptions. For those of us (including myself) who are not so mathematically inclined to understand the nitty-gritty details of Euclid’s Elements, Sir Thomas Heath sums them up in his 1908 publication The Elements of Euclid:

The 5 Axioms of Euclid:

1. Things which are equal to the same thing are also equal to one another

2. If equals are added to equals, the whole (sums) are equal

3. If equals are subtracted from equals, the remainders (differences) are equal

4. Things that coincide with one another are equal to one another

5. The whole is greater than the part

The 5 Geometric Postulates:

1. It is possible to draw a straight line from any point to any point

2. It is possible to extend a finite straight line continuously in a straight line

3. It is possible to create a circle with any center and distance

4. All right angles are equal to one another

5. If a straight line falling on two straight lines makes the interior angles on the same side less than two right angles, the straight lines, if produced indefinitely, will meet on that side on which the angles are less than two right angles.

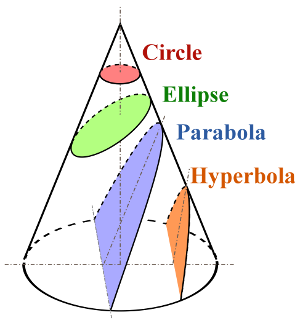

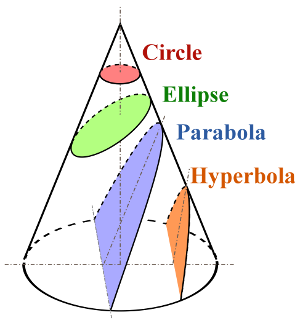

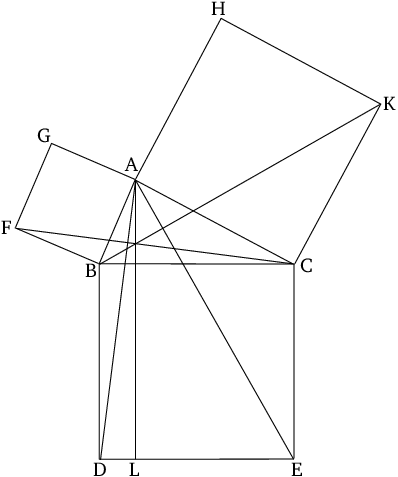

Other important contributions from Euclid is his proof of Pythagoras‘ Theorem, providing us with formulas that calculate the volumes of solids like cones, pyramids, and cylinders, as well as identifying the first four ‘perfect numbers,’ among a dozen or so other theories and proofs.

The most famous proposition from The Elements, Proposition 1.47. Also known as the Pythagorean Theorem.

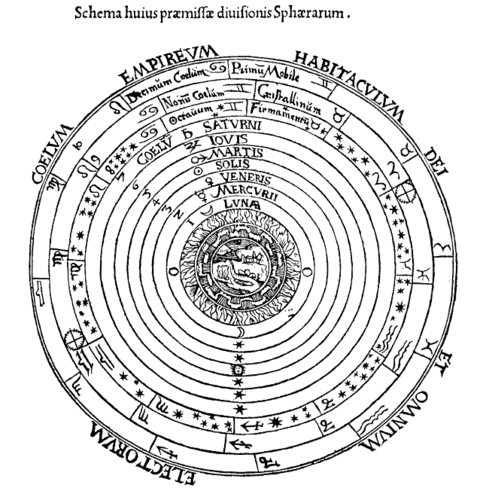

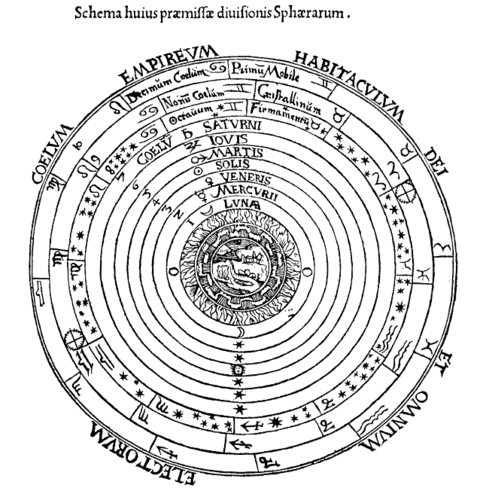

In addition to the Elements, five other works of Euclid have come down to us and have been able to be interpreted: Data, dealing with the nature and implications of “given” information in geometry; On Divisions of Figures, dealing with the division of geometrical figures into two or more equal parts or into parts in given ratios; Catoptrics, dealing with the theory of mirrors and the images formed in plane and spherical concave mirrors; Phaenomena, a treatise on spherical astronomy; and Optics the earliest surviving Greek treatise on perspective.

Euclid’s Death and Legacy

Euclid of Alexandria

We can assume that Euclid died in the mid-3rd century BCE in Alexandria, but that is all we know. However, he left behind a legacy that has survived almost two and a half millennia. His work on geometry and theory is still in use today, governing even advanced models of dimension mathematics. He is considered one of the greatest mathematicians to have ever lived, and a European Space Agency’s spacecraft was even named in his honor, the Euclid Spacecraft.