Written by Stefan Sencerz, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Parts 1 and 2 of this series focus on angels in the Western tradition. To read them, click

here and

here, respectively.

Angels in the Eastern Tradition

According to the Buddhist and Hindu scriptures, humanity has been migrating in the Grand Wheel of Life and Death, driven by our own karma that we have accumulated since time immemorial.

The Grand Wheel of Life and Death

Our own deeds determine a position, or a form of rebirth, in one of the “Six Realms of Existence”, defined as: humans, devas (heavenly dwellers, or as we might say in the West, angels), asuras (demi-gods or titans), animals, pretas (hungry and thirsty ghosts), or as beings tormented in one of numerous hells. What moves us from one realm to the other are emotions, dispositions, and blind desires, such as anger and hatred, cravings for pleasure, clinging to power and control. At the core of all of this is ignorance and lack of wisdom.

But no matter what drives us through the Wheel, no matter what obstacles and temptations we may encounter, and no matter what we are inclined to do, ultimately the decision is ours. Sometimes we yield to our cravings and attachments, and—driven by the winds of karma—continue being reborn.

However, we have an ability to transcend these desires, inclinations, cravings, and attachments and freely choose to follow the path of wisdom-compassion.

The realm of humans is considered the most auspicious in terms of spiritual awakening. In fact, some sources claim that it is the only condition allowing for such awakening or enlightenment.

Devas sporting in Heaven, mural in Wat Bowonniwet, Bangkok

Devas, or god-like beings, are frequently too preoccupied with pleasure to care about spiritual needs. Asuras, or demigods, are obsessed with power and jealousy. Animals lack intellectual abilities and their minds are not sophisticated enough to reach liberation. There is too much hunger and thirst in the lives of pretas, i.e., hungry and thirsty ghosts. And the enormous suffering in the realms of various hells makes spiritual practice borderline impossible.

Sometimes this myth is interpreted in two different ways. One view implies that the six realms denote real places where various beings are reborn; we might call this a “realist” interpretation. Yet another sees it as a symbolic representation of various “modes” of existence (e.g., of our various mental states and dispositions).

In this interpretation, it’s conceivable that various states sometimes coexist in one person, possibly even at the very same time. We might call this a “metaphorical” interpretation. These two interpretations are compatible; leaning towards one is frequently a matter of emphasis rather than accepting it exclusively and rejecting the other.

There is some textual evidence, both in Hindu and Buddhist writings, supporting the metaphorical interpretation of the myth. For example, early Vedas did not distinguish the realm of devas from the realm of asuras, they sort of lumped these beings together as if they were two aspects of the same mode of existence.

Consequently, in his commentary on the Vedic mythology, Ceylonese Tamil philosopher Ananda Coomaraswamy observed that devas and asuras exemplify different orientations and inclinations, rather than separate kinds of beings. Devas represent the powers of light while asuras represent the powers of darkness. Both kinds of powers exist in each and every human being. Consequently, our choices can be influenced by varying dispositions and intentions:

[T]he Titan is potentially an Angel, the Angel still by nature a Titan; the Darkness in actu is Light, the Light in potentia Darkness; whence the designations Asura and Deva may be applied to one and the same Person according to the mode of operation, as in Rigveda 1.163.3, “Trita art thou (Agni) by interior operation” (Ananda Coomaraswamy, “Angel and Titan: An Essay in Vedic Ontology,” Journal of the American Oriental Society, volume 55 (1935), pp. 373-374).

Similarly, according to the sixteenth chapter of Bhagavad Gita, all beings in the universe have both the divine and demonic qualities (daivi sampad and asuri sampad). Pure god-like saints are as rare as pure demons, and most humans exemplify both characters in varying degrees.

Statues of asuras at the gates of Angkor Thom, Siem Reap, Cambodia

A broadly analogous interpretation is suggested by some canonical Buddhist scriptures and Buddhist teachers. Indeed, the Buddha himself maintained that it is a mistake to think of hell as a place: “When the average ignorant person makes an assertion to the effect that there is a Hell (patala) under the ocean he is making a statement which is false and without basis. The word ‘Hell’ is a term for painful emotions”, he once said.

Consequently, preeminent Buddhist scholar and Theravada monk Sri Dhammananda Maha Thera, observes the following:

The idea of one particular ready-made place or a place created by god as heaven and hell is not acceptable to the Buddhist concept. The fire of hell in this world is hotter than that of the hell in the world-beyond. There is no fire equal to anger, lust or greed and ignorance. According to the Buddha, we are burning from eleven kinds of physical pain and mental agony: lust, hatred, illusion sickness, decay, death, worry, lamentation, pain (physical and mental), melancholy and grief. … [Where] there is more suffering, either in this world or any other plane, that place is a hell to those who suffer. And where there is more pleasure or happiness, either in this world or any other worldly existence, that place is a heaven to those who enjoy their worldly life in that particular place. (BuddhaSasana, “The Buddhist Concept of Heaven and Hell”).

This may be a somewhat unorthodox view of Ch’an and Zen approaches to Buddhism, but there are examples of famous Patriarchs supporting this metaphorical-humanistic interpretation of the Six Realms of Existence, thus shedding quite interesting light on how Buddhists think about paradise and hell.

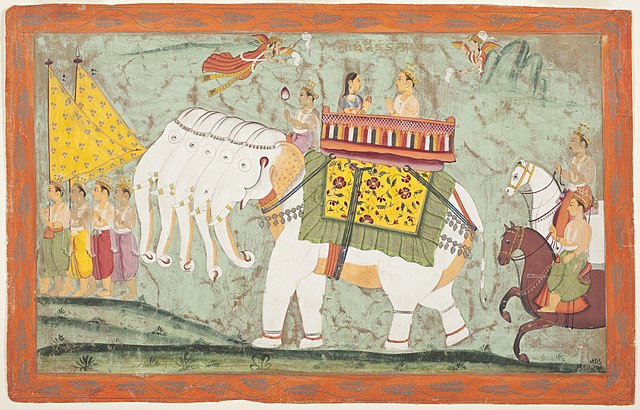

The Buddha Descending from Tavatimsa Heaven

For example, the 12th century Chinese Master Tai Hui:

Heaven and hell are nowhere else but in the heart of the person while he’s half awake and half asleep before he’s gotten out of bed—they don’t come from outside. (Cleary, J.C., Swampland Flowers: the letters and lectures of Zen Master Ta Hui, Shambhala, 2006)

The same spirit is expressed in the following famous story involving the great Japanese Zen Patriarch, Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1769):

A samurai came to the Zen Master Hakuin and asked “Is there really a paradise and a hell?”

Who are you?” inquired Hakuin.

“I am a samurai,” the warrior replied.

“You, a samurai!” exclaimed Hakuin. “What kind of ruler would have you as his guard? Your face looks like that of a beggar!”

The soldier became so angry that he began to draw his sword, but Hakuin continued. “So, you have a sword! Your weapon is probably as dull as your head!”

As the soldier drew his sword Hakuin remarked “Here open the gates of hell!”

At these words, the samurai, perceiving the discipline of the master, sheathed his sword and bowed.

“Here open the gates of paradise,” said Hakuin.

(A version of this story appears in Zen Flesh, Zen Bones: A Collection of Zen and Pre-Zen Writings compiled by Paul Reps and Nyogen Senzaki, Tuttle Publishing 1998, p. 80. A search for this story in Japanese returns many slightly rephrased results but no one cites a source. It seems like it is an oral teaching. For generation, people have been retelling it with slight alterations before it was written down.)

End of Part 3 of 4