By Edward Whelan, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The Battle of Nisibis (217 AD) was the last battle between the Roman and the Parthian Empire. They had battled each other regularly for almost three centuries. This two-day battle was a particularly brutal and bloody one.

Parthian horse archer

The Background to the Battle of Nisibis

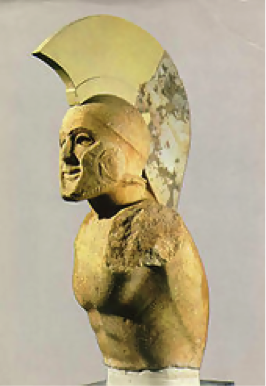

Caracalla was one of the bloodiest tyrants ever to rule Rome. He murdered his own brother and massacred the inhabitants of Alexandria. He was possibly mad and believed himself to be a second Alexander the Great. In 216 AD Parthia was convulsed by a civil war between King Atrabanus V and his brother. Caracalla decided to take advantage of this, to seize more territories. He first cunningly offered to marry the daughter of Artabanus V, but the Parthian monarch rejected his proposal.

Caracalla used this refusal as a pretext to invade Parthian lands, in the process he broke a peace treaty between the two states. He invaded what is now Northern Iraq and devastated it and committed many atrocities before he retreated back into Roman territory, for winter. Caracalla had become increasingly unpredictable and his inner circle feared him greatly. The Prefect of the Praetorian Guard Macrinus killed the crazed tyrant and seized the throne in April 217.

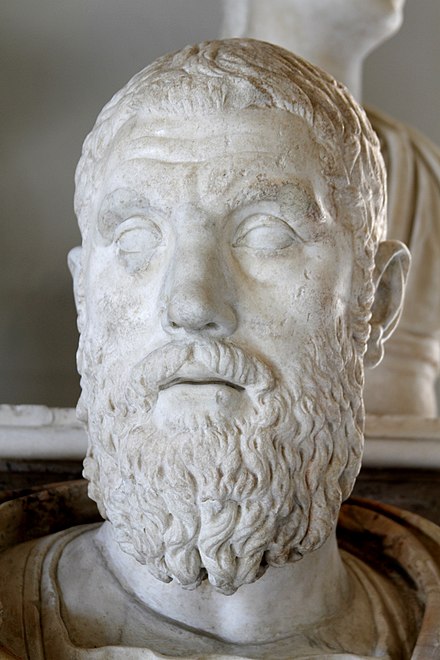

A bust of the Emperor Caracalla

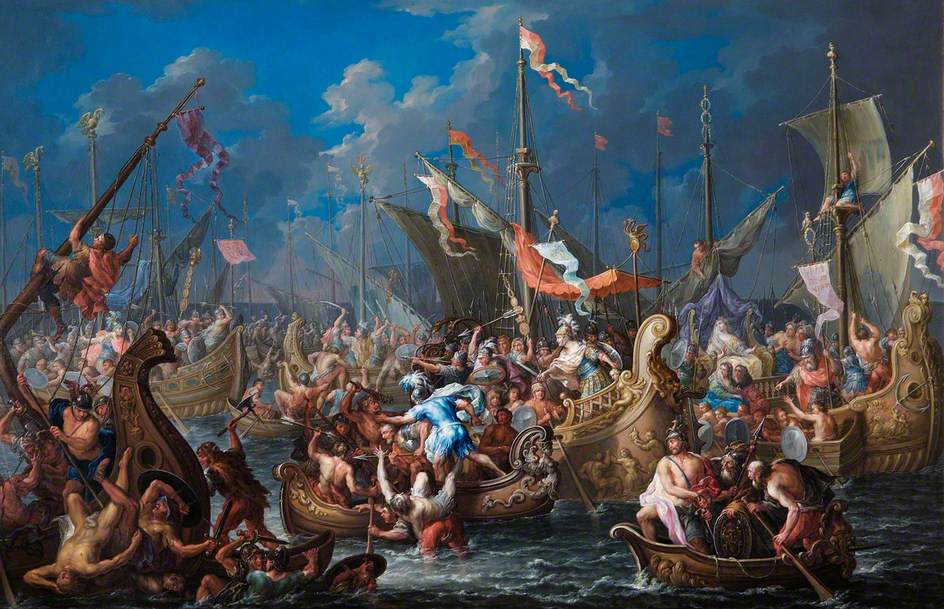

The Battle of Nisibis

Artabanus and the Parthians were enraged by Caracalla’s outrageous behavior. The Parthians invaded Roman territory. As the new emperor Macrinus had no military experience, he sought a diplomatic solution. The Parthian monarch and his men, however, wanted revenge. It should be noted that they did not know that Caracalla was already dead and that there was a new Emperor.

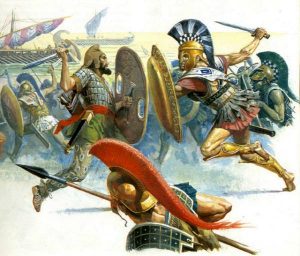

The two armies met in the Armenian Highlands, near the city of Nisibis, in what is now Eastern Turkey. Macrinus’ army was mainly infantry based while the Parthians were overwhelmingly cavalry. The Romans had legionnaires, archers and skirmishers, largely javelin throwers. The Parthians had heavily armored horsemen, known as cataphracts, precursors to medieval knights, and javelin throwers riding camels.

The Romans were positioned on sloping ground. The heavily armored troops were lined up in a defensive line, while the cavalry and light troops guarded their flanks.

Bust of Macrinus

On the first day, Artabanus reminded them of the recent atrocities committed by the Romans and then ordered them to attack. The camels, cavalry and light troops of the Parthians advanced and made some gains, inflicting heavy casualties on the Romans light troops, mainly Auxiliaries.

Macrinus’ forward units retreated but as they did, they left crow’s feet behind them. These were pointed steel devices which the Parthians camels and horses stood on. This led to terrible injuries and many riders were killed after being thrown from their saddles. The Parthians were not deterred. Their famous mounted archers fired volley upon volley of arrows on the Roman lines. This continued until dark; the death toll was very high and the moans of the dying could be heard throughout the night.

The morning of the second day, the battle opened up with the Parthians camel-back javelin throwers inflicting heavy casualties on the Romans. By the late morning, the heavy cavalry of the Parthians attacked the mainline of the Romans. However, at close quarters the heavy Roman infantry was able to beat back the attackers. Macrinus’ army had no relief as the Parthians, furious at the crimes committed by Caracalla, were in a frenzy. They wanted Roman blood.

A modern re-enactor dressed as a Cataphract

Seeing that a frontal assault was getting him nowhere, Artabanus ordered an attack on the flanks. This heavy cavalry almost succeeded in pushing back the flanks of the Romans. However, Macrinus’ men extended their line and Moorish javelin throwers helped to inflict heavy casualties on the Parthian cataphracts and camel-riders. This saved the Romans from being encircled and potentially annihilated.

By the end of the second day, there were dead men, horses, and camels all over the battlefield. They were piled so high that in places the Parthian cavalrymen could not move.

The Roman Emperor was desperate, his men had sustained heavy casualties and he believed that his army might not be able to withstand a third day of near-suicidal enemy attacks.

A diplomatic compromise to The Battle of Nisibis

Macrinus was a shrewd political operator and he came up with an ingenious plan to save his forces. He sent a delegation to Artabus and explained that Caracalla was now dead and that he was fighting the man who had killed him. Therefore, Macrinus stated that Artabus had no more reason to fight and that he had already been avenged. Artabus had lost many men and many of his cavalry had become restless, as they were far from home.

Coin of Artabus IV

He demanded that Macrinus cede a province to the Parthians. However, the Roman Emperor was a better diplomat than soldier and was able to secure an end to the war simply by paying a huge sum of gold. The Parthians soon withdrew to their own lands, and they are widely seen as the victors in the battle.

Aftermath of The Battle of Nisibis

Macrinus was defeated in battle and executed by a distant relative of Caracalla in 218 AD. His young son was also murdered by the new Emperor, Elagabalus.

Artabus V is often regarded as the victor of Nisibis. However, he soon faced a major revolt by the Sassanians in what is now Iran. The Sassanians, under Ardashir, defeated Artabus V. Ardashir went on to take over the Parthian Empire and is considered to be the founder of the Sassanian Empire.

The Battle of Nisibis was to prove the last battle between Rome and Parthia. However, the Romans were to fight a new and more formidable enemy: the Sassanians.