You might remember two weeks ago we had something of a chat about a rather interesting bit of history. How is it that an alliance of cities with the unobjectionable goal of protecting their homeland from foreign invaders eventually turned into one of the first  empires of the ancient world?

empires of the ancient world?

Well, it’s kind of a funny story, albeit not a very original one. Anybody with a basic understanding of history, or human nature, will recognize the cycle. A government comes to power and a country, often through conquest, rises to prominence. Once they have gotten a taste of the good life, so to speak, they are rather reluctant to go back to the way things used to be.

And so by force or by fraud, the government takes it upon itself to maintain the status quo, to preserve their prosperity.

It seems as if Bill Bonner, over at Diary of a Rogue Economist, was thinking the same thing this week when he wrote…

“Governments were set up to take control. Ruling elites – by force of arms – established laws, protocols and armies to try to prevent anyone from taking their place. Their wealth, power and status were to be preserved at all costs.” –Bill Bonner’s Diary of a Rouge Economist (April 1st, 2015)

I really could not have said it better myself. The article continues by detailing how ruling elites throughout history maintained their status by force right up until the advent of the firearm. After all, every farmer in the American colonies had a rifle. As a result, a ragtag group of insurgents (with the assistance of the French Navy) were able to defeat the greatest army in the world.

So, the newsletter continues, the powers that be had to find another way to keep the commoners in their place. They turned to fraud.

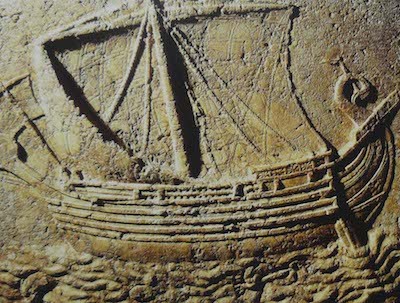

Now that is all very interesting. But keep in mind that our topic of interest took place over two thousand years ago; back in the good old days when whoever had the most guys with pointy sticks was inevitably the top dog. And as we discussed last week, Athens, after a few decades in the Delian League, had an abundance of pointy sticks, warships, and men willing to go to war for glory and loot.

If you are not an avid Classical Wisdom Weekly reader, then you can catch part one of this article by clicking here. Go ahead. I’ll wait.

Back already? Wonderful! Let’s recap.

The year is 479 BC and the Greek alliance has just expelled the Persian Empire from the Hellenic mainland. The entire Greek force is basking in PanHellenic pride. The following year, a congress of about 150 city-states makes an alliance on the island of Delos. The purpose of this “Delian League” was to continue to battle the Persian forces in Northern Greece, Asia Minor, and the Aegean islands.

The de-facto leader of this alliance is Athens. With the dues paid by the other allied cities, the Athenian government builds up their already impressive navy and begins a series of successful military engagements against the Persian armies.

Athens collects the looted treasures of the cities they conquer while continuing to receive dues from member states. It is estimated that the league was collecting hundereds of millions of dollars in contemporary terms every year. With an adult male population of about 45,000 in Athens, this meant unrivaled prosperity for the Athenians.

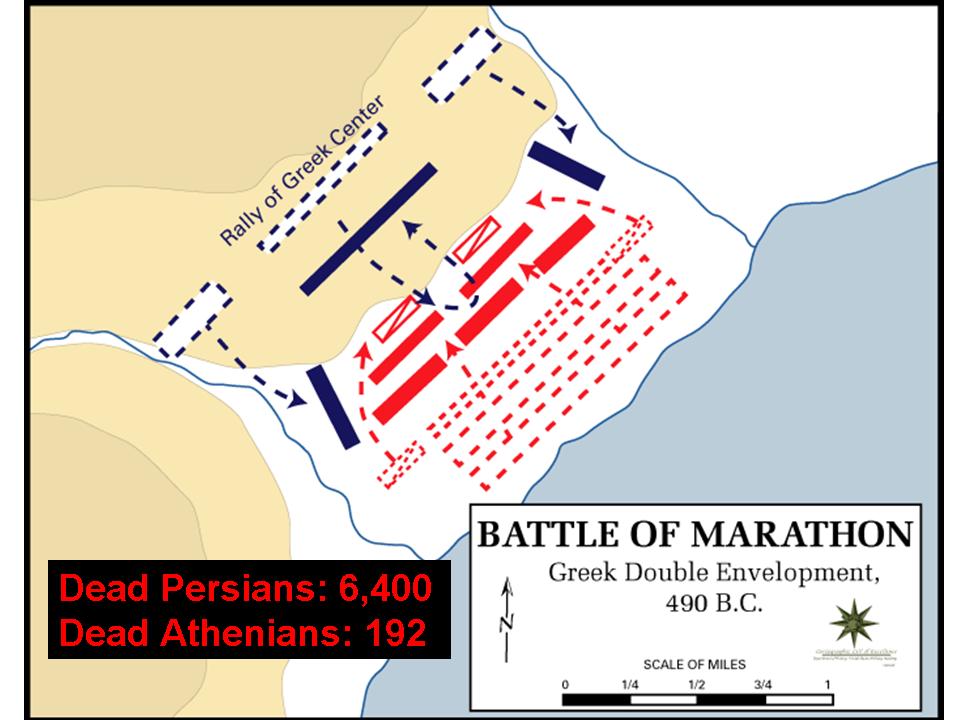

Additionally, the continued success of the Delian League armies brought more glory for the Athenian elite. Men like Cimon, an Athenian general who was the son of the hero of the Battle of Marathon, continued to cement his place within his cities most privileged faction with each victory over the Persian forces.

The Athenian commoners, perhaps surprisingly, also benefited from the continued existence of the Delian League and the military campaigns. Unskilled laborers could be hired as rowers on Athenian triremes. It is estimated that a rower could make as much in a month as a farmer could make in a year.

Put very simply, the Delian League had propelled Athens to a level of prosperity that had been unheard of during this time. Athens had every reason to maintain the alliance, and they would do anything to prevent a loss of power.

Athens’ determination to maintain the hegemony can be seen in 465 BC when they lay siege to the island of Thasos after the island’s government had unilaterally voted to withdraw from the league. Athens conquered the city-state, tore down its walls, confiscated its navy, and forced the island to continue to pay tribute.

Naxos and the city of Erythrai in Asia Minor were similarly put down and subjected to Athenian rule after they had attempted to withdraw from the alliance. The Delian League was a union now only in name. There were no allied uprisings during this time that were not swiftly squashed by the Athenian military.

“The subject states of Athens were especially eager to revolt, even though it was beyond their capability.”

(Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book VIII)

After these allied revolts, and the subsequent force enacted by Athens to maintain control, a new type of member emerged within the Delian alliance: a subject state. These members, members like Naxos and Thasos, were ruled over by Athenian garrisons and acted as Athens’ puppets within the leagues assembly.

Combining these members with the smaller city-states who were either intimidated by Athens or relied upon her for protection, the outcome of assembly votes was never in question. Whatever Athens wanted would always be done. The assembly would not even bother considering military action if it did not clearly benefit the Athenian interests.

The assembly would eventually become irrelevant and was disbanded around 435 BC. Athens continued to rule by decree alone. Their empire was well and truly established.

“After the Athenians had gained their empire, they treated their allies rather dictatorially, except for Chios, Lesbos and Samos. These they regarded as guardians of the empire, allowing them to keep their own constitution and rule over any subjects they happened to have.”- Aristotle

(Consitution of Athens)

What is interesting is that this rapid Athenian expansion did not take place under the rule of an oppressive tyrant, nor was it a series of oligarchs that made designs to craft an empire. Athens’ policies of extreme imperialism came about during a time of what some refer to as “radical” democracy.

It was during this time that significant reforms were set in place. Athenian citizens could participate on juries, for the first time in the city’s history. Juries often determined the guilt of a defendant after only one round of voting and there could be no appeals.

Additionally, the office of general (strategos) was voted upon directly by the citizenry of Athens. It is for this reason that the Athenian generals, wishing to maintain the support of the populace, were so bold, and occasionally over eager, to participate in further military expeditions.

It is ironic that this type of Athenian democracy, which aimed at achieving absolute egalitarianism for the Athenian citizens, was never allowed for the other member states within the alliance. Any states attempting to achieve any semblance of independence from Athens were struck down by force.

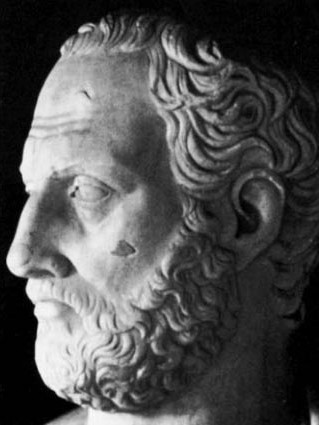

Athenian expansionism would continue into the 450’s when a wealthy aristocrat named Pericles came to the fore. Smart, affluent, and wildly popular with the commoners, Pericles would be the dominant politician in Athens for the next two decades.

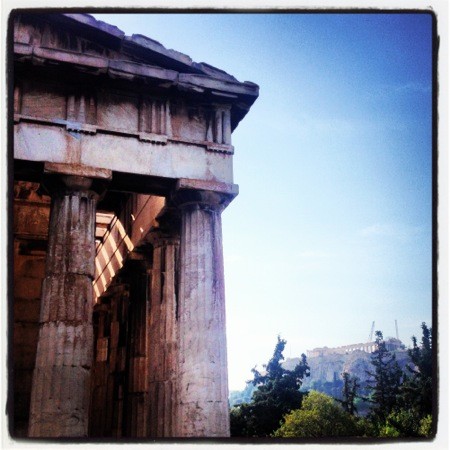

While Athens had indeed established itself as an imperial force, the Athenian city looked anything but. Much of the damage inflicted by Xerxes’ army several decades earlier had never fully been repaired. Many of the Athenian assembly meetings consisted of men lounging on a hill in the ancient Agora. Athens needed a lesson in playing the part of a magnificent empire, and Pericles was here to show them how.

In 454 BC Pericles moved the Delian league’s treasury from the neutral island of Delos and stored it within the Athenian acropolis. The official reason for the transfer was so that the treasury could be protected from Persian invaders or marauding pirates. Plutarch, however, suggests that there might have been an ulterior motive.

“…the demagogues enlarged it (the treasury) little by little, and at last brought the sum total up to thirteen hundred talents, not so much because the war, by reason of its length and vicissitudes, became extravagantly expensive, as because they themselves led the people off into the distribution of public moneys for spectacular entertainments, and for the erection of images and sanctuaries.” –Plutarch (Life of Aristides)

Pericles had initiated public building projects in 454 BC. As a result, many of the most iconic structures of the ancient world were erected during this time; chief among them is the Parthenon. And while the building projects were funded primarily through Athenian taxation and donations from Athens’ wealthiest, Plutarch seems to suggest that the building of the Parthenon, at least partially, was funded by the tributes paid by the league.

If this is correct, then it would mean that funds intended to be used for the protection of all of Greece had been spent by the Athenians to create their magnificent temples. This is often pointed to as being one of the first embezzlement scandals of the Western world.

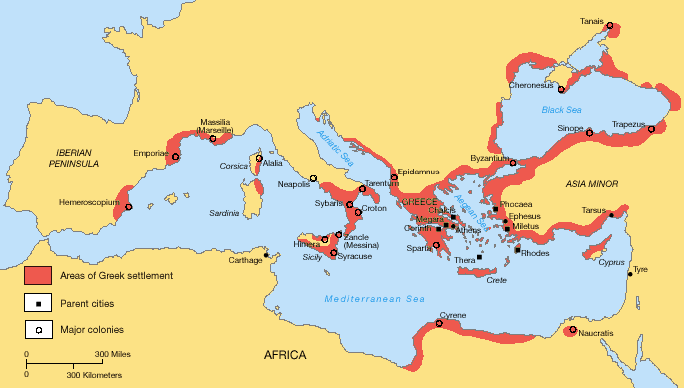

In addition to his expansive building projects, Pericles established colonies on confiscated lands as a means to discourage revolts from Athenian subjects.

“Pericles sent out one thousand settlers to the Khersonese, five hundred to Naxos, 250 to Andros, one thousand to Thrace to make their homes with the Bisaltai … and, by setting up garrisons among the allies, to implant a fear of rebellion.”

(Plutarch, Life of Pericles)

Athens’ rapid rise to power and their tendency to bully their neighbors into getting what they wanted had not gone unnoticed. Sparta had watched the rise of the Athenian empire with a weary eye. And here we come to the crux of our story.

In the words of Thucydides…

“The growth of the power of Athens, and the alarm which this inspired in Lacedaemon, made war inevitable.” –Thucydides (History of the Peloponnesian War, Book I)

Athens had managed to broker a peace with Sparta in 445 BC. However, Athens’ continued support of Spartan enemies would increase tensions over the next fifteen years. In 431 BC, there could be no more truce. Fighting broke out, and the Peloponnesian War had officially begun.

The fighting would last for thirty years. During that time Athens saw the death of Pericles, the introduction of a terrible plague, and the defection of one of their greatest generals, Alcibiades.

The fighting would last for thirty years. During that time Athens saw the death of Pericles, the introduction of a terrible plague, and the defection of one of their greatest generals, Alcibiades.

In 404 BC, faced with starvation, disease, and a Spartan army laying siege to their city, the Athenians surrendered. They were stripped of their walls as well as all their overseas possessions. Athens’ system of democracy was disbanded. The Athenian Empire had fallen.

The Athenians ought to have counted themselves lucky that the Spartans did not destroy their city and scatter the populace. After their victory, the Spartan government allowed Athens, a city that had done so much for the Greek people, to limp on.

So what can we learn from all this? Well, we can see that the intentions of the Athenians at the birth of the Delian League had been largely honorable. They wished to protect their homeland and maintain an alliance amongst their neighbors.

However, the continued success of the league brought Athens unrivaled prosperity and power. Once they had a taste of true supremacy, they could not give it up. Athens would attempt to maintain their dominance by force, subjugating long-time allies and creating resentment among their neighbors. There could be only one outcome for the Athenian empire: violence, war, and eventual collapse.

The rashness of the Athenian assembly was partially due to its democratic nature. While oligarchs might have been more reserved when it came to continued expansion, the Athenian generals were consistently pushed to adventurism again and again because of the potential reward it held for the people as well as for their political clout.

For this reason, the story of the Athenian Empire is often looked at as more than just an interesting historical anecdote. It is an endearing testament to the true nature of man and the potential danger of democracy. Put in the same position, any of us would have done the same. Thucydides put it best when he wrote…

“We have done nothing surprising, nothing contrary to human nature, if we accepted leadership when it was offered and are now unwilling to give it up.” –Thucydides (History of the Peloponnesian War, Book I)

empires of the ancient world?

empires of the ancient world?

The fighting would last for thirty years. During that time Athens saw the death of Pericles, the introduction of a terrible plague, and the defection of one of their greatest generals, Alcibiades.

The fighting would last for thirty years. During that time Athens saw the death of Pericles, the introduction of a terrible plague, and the defection of one of their greatest generals, Alcibiades.  However, once the fighting is over, the typical thing to do is to fast-forward a few decades to when the next epic struggle for supremacy took place, The Peloponnesian War. After all, who doesn’t love a bit of military history?

However, once the fighting is over, the typical thing to do is to fast-forward a few decades to when the next epic struggle for supremacy took place, The Peloponnesian War. After all, who doesn’t love a bit of military history?