By Edward Whelan, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

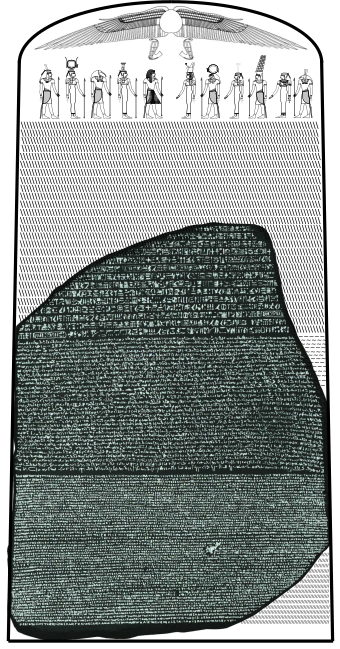

Ancient Egypt has fascinated people since ancient times. However, the history and knowledge of the land of the Pharaohs were lost for centuries because people were unable to read the ancient writings of the Ancient Egyptians…that was until the chance discovery of the Rosetta Stone. This remarkable artifact allowed the modern world to once again read the texts of the Ancient Egyptians.

Egyptian writing

Ancient Egyptians used hieroglyphs in their writing system, which are pictographs that represent some concept or idea and is very different from those based on alphabets. However, they also developed a demotic script that was similar to other writing systems, such as Greek and Latin. Following the Christianization of Egypt, knowledge of the ancient writing systems was lost because the Egyptian priests were persecuted, and their temples all destroyed. As a result, the world of the Pharaohs and their subjects remained a mystery.

The History of the Rosetta Stone

The writings of the Egyptians remained enigmatic until the invasion of Egypt by Napoleon. In order to outflank the British in 1798, the French general decisively defeated the Mamelukes, the descendants of slave-soldiers who ruled the country, at the Battle of the Pyramids. Napoleon also brought with him to Egypt scientists, historians, and other researchers. They played a very important role in the development of Egyptology, which opened up the wonders of Ancient Egypt to the West.

The most important discovery was the stele that came to be known as the Rosetta stone.

One day in the hot summer of 1799, a French officer and engineer, Pierre-François Bouchard, was overseeing work on a planned fortress in Rosetta, an important port in northern Egypt. When he came across a stele or monument that was made from a block of granite, he knew it was important and alerted experts. The officer had discovered one of the most famous artifacts in Egyptology.

The Battle of the Pyramids

The Rosetta Stone- What Is It?

The stone is a stele which has engraved on three sides a decree that was issued by Pharaoh Ptolemy V in 196 BC. He was a member of the Macedonian Ptolemaic Dynasty that was founded by one of Alexander the Great’s generals. The decree was a ruling from a priestly council in Memphis which granted the monarch the status of a living god and urged Egyptians to make sacrifices to the new god-king. This was an effort by Ptolemy V to legitimize his rule in the eyes of his Egyptian subjects, who hated their Macedonian overlords.

The granite piece stood in a temple for many centuries but when Christians closed it, the stele was used in the foundation of a new building. The original stele was broken up, and what remained was the largest fragment. It was later incorporated into the foundation of a building during the Middle Ages and laid there until it was rediscovered by the French officer.

One possible reconstruction of the original stele

The Rosetta Stone’s Writing

The stone is not important in itself. However, what makes it priceless is that it contains three different versions of the decree of Ptolemy V. There is Greek which was the language of court and the Macedonian elite who ruled the country. However, the vast majority of Egyptians could not read Greek and could only read demotic Egyptian or Hieroglyphs. This meant that the decree was also issued in demotic and hieroglyphs. This was a stunning find.

Experts could read Ancient Greek and indeed were very proficient in it. They could use the Greek to learn how to decipher the two Egyptian texts. In this way, they knew that they had a great opportunity to finally understand the writings of the great and mysterious Pharaohs.

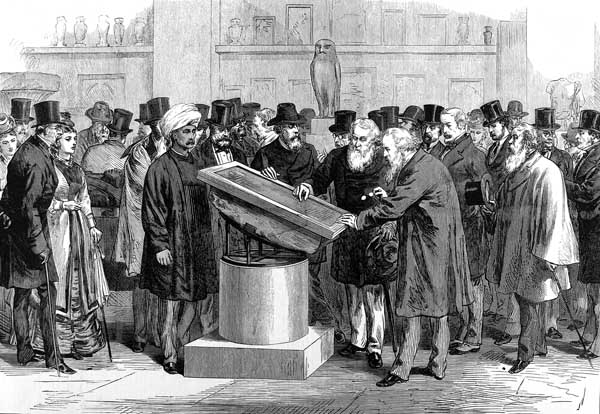

Experts inspecting the Rosetta Stone during the Second International Congress of Orientalists, 1874

The discovery of the stone and other treasures led to a craze in Europe for all things Egyptian.

The Race to Decipher the Stone

Technically it should have been easy to decipher the decree, especially as the French made impressions of the writings and they were published and circulated all over Europe. Classicists and linguists all studied the writings in a race to be the first to read the words of the Ancient Egyptians.

It took many years before a breakthrough in 1803 when the first full translation of the Greek version of the decree appeared. However, here was a great rivalry between experts, in particular the French and English, with regards to the Egyptian texts. Finally, in 1822 Jean-François Champollion announced he had made a successful transcription. He was the first person to fully decipher the stone and allowed people for the first time in centuries to read the writings of the Pharaohs. It’s important to note still that his work was only possible because of the earlier research of English linguists, especially Thomas Young.

The Fate of the Stone

Nelson’s great victory over the French at the Battle of Aboukir Bay (1799) doomed Napoleon’s invasion. He soon fled back to France and the stone was seized by the British after they defeated the French in 1801. The stele was taken back to London where it has remained ever since. It can be seen to this day in the British Museum.

References

Ray, J. D. (2007). The Rosetta Stone and the Rebirth of Ancient Egypt. Harvard University Press.

By David Grant, Author of Unearthing the Family of Alexander the Great, the Remarkable Discovery of the Royal Tombs of Macedon

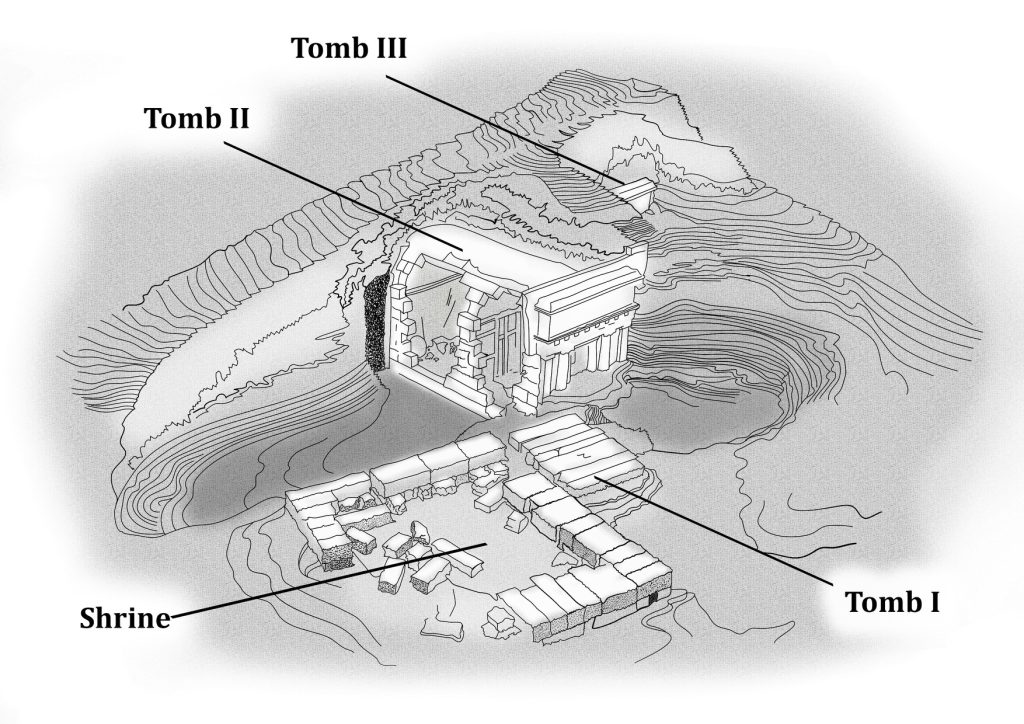

In November 1977 the ‘archaeological discovery of the century’ emerged from soil below a great tumulus at Vergina in northern Greece. Eventually four tombs and a shrine would be unearthed and dubbed the ‘cluster of Philip II’, the father of Alexander the Great. But the hopeful identification led to a backlash from scholars who questioned the archaeology.

Following thirty years of claims, counter-claims and deep divisions within the academic community, the ‘battle of the bones’ over the identities of the ‘king’ and ‘queen’ buried in Tomb II had led to nothing but a Socratic truth: ‘all I know is I know nothing for sure.’ The cremated skeletal remains from antiquity still lay silent and anonymous, but they had not been devoid of ‘nationalist’ political controversy.

In the name of ‘national’ archaeology

In 1991 Yugoslavia dissolved and out of the fallout emerged a new socialist republic to Greece’s north. Its borders fell between Albania and Bulgaria in what would have been largely ancient Paeonia and western Thrace in the time of Philip II’s predecessors. Arguably a slither of ancient ‘Upper Macedonia’, the northern cantons annexed by Philip in his expanded realm, fell into the new state. Despite the questionable geopolitics, the new Republic of Macedonia immediately adopted a twelve-point Vergina starburst of the Argead kings to adorn its national flag.

Greece saw the republic’s name and its flag as national identity theft and demanded both be changed. Street protests followed on both sides of the border and airport names were changed in line with each nation’s cause. The new regime was duly recognized by the United Nations in 1993, but only under the title ‘Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia’ (‘FYROM’). Claiming ancient roots in the region under a tide of nationalism, FYROM accused its neighbor of stealing the biggest part of ‘Aegean Macedonia’ and incorporating it into northern Greece. The response from Athens was a blockade of the new Balkan player staking identity claims to the kings buried below Vergina.

The tides of politics had always tugged at the archaeology attached to Vergina and the lack of harmony between ministries responsible for antiquities resulted in a chronic lack of funding needed to make forensic progress. But the tomb debate was finally given forward momentum in 2010 when an anthropological team led by Professor Theo Antikas, with a modest 6,000-euro grant from the Aristotle University of Thessalonica, commenced a several-month task of cataloguing the Tomb II bones; their ground-breaking study would last five years.

The excavator’s proposition that Philip II and one of his wives were interred in Tomb II had always been undermined by an early ‘quick’ prognosis by a UK-based anthropologist; he had taken a ‘cursory’ look at the skeletal remains found scattered in the soil infill of looted Tomb I and his ‘tentative’ findings concluded the cist chamber housed a well-built male in the prime of his life, a young woman and a newborn baby or foetus.

What the anthropologist unwittingly did was to give ammunition to the faction backing Philip III Arrhidaeus and Adea-Eurydice as the residents of Tomb II. By concluding that the Tomb I bones were those of a middle-aged man, a young woman and a baby, he had all but described the events surrounding the death of Philip II, whose young wife Cleopatra and her newborn were executed by his estranged wife Olympias, Alexander’s mother. If they were buried in Tomb I with its beautiful wall fresco, Arrhidaeus and Adea must have resided in Tomb II. But that was not what the anthropologist believed at all.

The Tomb I bombshell

This theory was finally put to the sword by an ‘identity-shattering’ discovery made by the Antikas team. In 2014 they came across forgotten and unanalysed skeletal remains from Tomb I in storage below the Vergina laboratory. These bones were probably consigned to thirty-five-years of obscurity in the aftermath of the ‘great’ Thessalonica earthquake of 20 June 1978 when the preservation of the unlooted Tombs II and III was the focus of attention. These additional Tomb I skeletal fragments contained the remains of at least seven individuals, not two just adults and a baby. An ugly fact had once again slayed an attractive idea.

To effectively analyse and then catalogue the Tomb II bones, the Antikas team resorted to computed tomography (CT) scanning, then each bone was catalogued with a unique number, with entries on weight, condition and morphological changes such as colour, warping or cracking. Any signs of foreign materials such as rare minerals were noted, along with comments on the conservation condition from previous handling. They next photographed each fragment from every anatomical plane, capturing over 4,000 images.

Some 350 male bones had been found in the gold chest in the main chamber. His skeleton weighed in at 2,225.8 grams, remarkably close to the mean weight, 2,283 grams, of adult male cremation remains today, a testament to the care with which the bones had been collected from the funeral pyre.

Yet, with all the modern technology at hand, on occasion there is no replacement for intense scrutiny with a simple magnifying glass. Using no more than a hand-held lens, they determined the Tomb II male suffered from a respiratory problem, a chronic condition that could have been pleurisy or tuberculosis, evidenced by the pathology they found on the inside surface of his ribs. Visible ‘wear and tear’ markers on his spine indicated he had experienced a life on horseback, while further age-related changes to the male skeleton, which had not been brought to light before, allowed the Antikas team to narrow down the estimate of the Tomb II male to 45 +/– 4 years at death.

The limping ‘Amazon’

In another ‘eureka moment’, the team identified a major shinbone fracture which had shortened the left leg of the female in Tomb II. This was a significant find as it conclusively united her with the antechamber armour, because the left shin guard or greave of a gilded pair, which had always looked rather ‘feminine’ in proportion, was 3.5 cm shorter and also narrower than the right. That, in turn, linked her to the weapons which lay beside them. Historians now had the conundrum of a limping warrioress with a precious artefact from the Scythian world.

Theo Antikas with Laura Wynn-Antikas holding the shorter greave in the Archaeological Museum of Vergina

Closer analysis of the previously unseen complete pubic bone aged her at 32 +/- 2 years years at death, and that ruled out both the earliest and the most prominent of Philip’s wives who were too old when he died, and also his final teenage bride, Cleopatra, as well as the equally young Queen Adea-Eurydice, the wife of Philip’s half-witted son Arrhidaeus. But the ‘intruder’ question remained: what was a Scythian artefact doing in a Macedonian tomb?

David Grant, a historian of the period who has collaborated with the Antikas team for the past three years, doesn’t see the need for a ‘foreign’ identity, despite the Scythian-styled quiver: ‘the Scythians were not renowned as metalsmiths; the exquisite jewellery we find in their graves is the workmanship of overseas Greeks, likely from the Bosporus Kingdom, close to today’s Crimea in the northern Black Sea.’

But there was also a thriving metalworking industry in Macedon itself, where weapons and armour were fashioned for Philip II. The possible domestic manufacture of what could have included ornate goods for Scythian warlords, with whom diplomatic links were being forged in the era of Philip, means the ‘Amazon’ of Vergina could have been born rather closer to home’. Grant has now proposed a new identity for the Tomb II warrioress.

In doing so Grant highlights the prominence of politically empowered women in Macedon during and after the reign of Philip and his son. There was even a pivotal conflict termed the ‘First War of Women’ between Alexander’s Epirote mother Olympias and Arrhidaeus’ young martially trained wife, the part-Illyrian Adea-Eurydice, in the scramble for power in the post-Alexander years. The now-preeminent nation into which Philip had ‘imported’ foreign brides’ was not short of pugnacious women prepared to ‘weaponise’ themselves!

Orphic mask and burial rituals

The Antikas team comprised both anthropologists and material scientists. Their additional microscopic finds, including textile stains, composite material fragments and melted metals on the cremated skeletons, hinted at ancient burial rituals, a death mask and the profound belief in the afterlife as part of the funerary rites.

The rare white mineral huntite was discovered with Tyrian Purple on the bones of the Tomb II male, bound with egg-white in layers. This clearly man-made composite material which evoked a vivid image of an unknown Orphic funeral rite involving a white death mask of the type found at Mycenae as well as other Bronze-Age and Archaic-Period graves. Melted gold on the upper vertebrae suggested the king was initially wearing his gold wreath as flames licked the funeral pyre, because the incomplete oak-leave-shaped wreath found inside the tomb showed similar signs of intense heat.

There may even be fragments of a fireproofing asbestos shroud which wrapped the cremated male, just as the Roman naturalist Pliny claimed was the practice of ancient Greek kings to separate the bones from the rest of the pyre debris. What had also become clear in the study was that the bones of the ‘king’ and ‘queen’ were subject to distinctly different pyre conditions, supporting the idea that they were cremated at different times.

‘Final-solution’ forensics

The Antikas team’s finds were published in an academic journal 2015. Although hampered by continued underfunding and a seeming lack of support from those fearing unwanted results, they continued to push for ‘next-generation’ forensics: DNA testing, radiocarbon dating, and stable isotope analysis on the Tomb II and Tomb III bones.

Permission was denied in 2016, Grant reveals. Instead the scientists were only allowed to test the scattered bones found in looted ‘Tomb I’ and a nearby ‘hidden’ burial pit found nearby the ancient city marketplace, but no formal funding was provided to facilitate the study.

Although these bones lay exposed in soil and water for over 2,000 years, dating and DNA results were successfully extracted, disproving yet more of the identity theories. Moreover, controversial Tomb I leg bones, which had been introduced into the ‘battle of the bones’ as supposed evidenced the terrible a knee wound Philip may have suffered in Thrace, appeared under scrutiny to be ‘intruders’ from a completely different tomb. The results have not been previously published and they will amaze everyone, says Grant.

Gold wreath found sitting in muddy water with the cremated bones of an adolescent male near the ancient marketplace of Aegae.

What the results incontestably tell us is that the great earthen tumulus at ancient Aegae was bitten into by looters on more than one occasion, when the exposed Tomb I became a dumping ground for the dead.

Now Grant’s new book is revealing all, the pressure will certainly be on the Greek Ministry of Culture to take a new progressive stance on permitting the outstanding forensics on the ‘royal’ bones from the unlooted tombs. With the possible identities greatly narrowed down by the Antikas-team study, new DNA, radio carbon dating and stable isotope analysis of the ‘king’, ‘queen’ and ‘prince’ may solve the puzzle once and for all.

In Grant’s opinion, ‘the “bones” are the real magic of Vergina’ where a steady stream of tourist buses arrives every day to visit the ruins and subterranean museum which houses the still-visible tombs and gold and silver artefacts. His book is set to raise more than eyebrows as it unveils the untold backstory of the royal tombs of Macedon.

Unearthing the Family of Alexander the Great, the Remarkable Discovery of the Royal Tombs of Macedon by David Grant is available from Amazon and all major online book retailers.

By David Grant, Guest Author, Classical Wisdom

On November 8, 1977, ‘Archangel’s Day’ in Greece, an excavation team led by Professor Manolis Andronikos was roped down into the eerie gloom of a rare Macedonian-styled tomb at Vergina in northern Greece. Dignitaries, police, priests and politicians watched on as the first shafts of light in 2,300 years penetrated its interior.

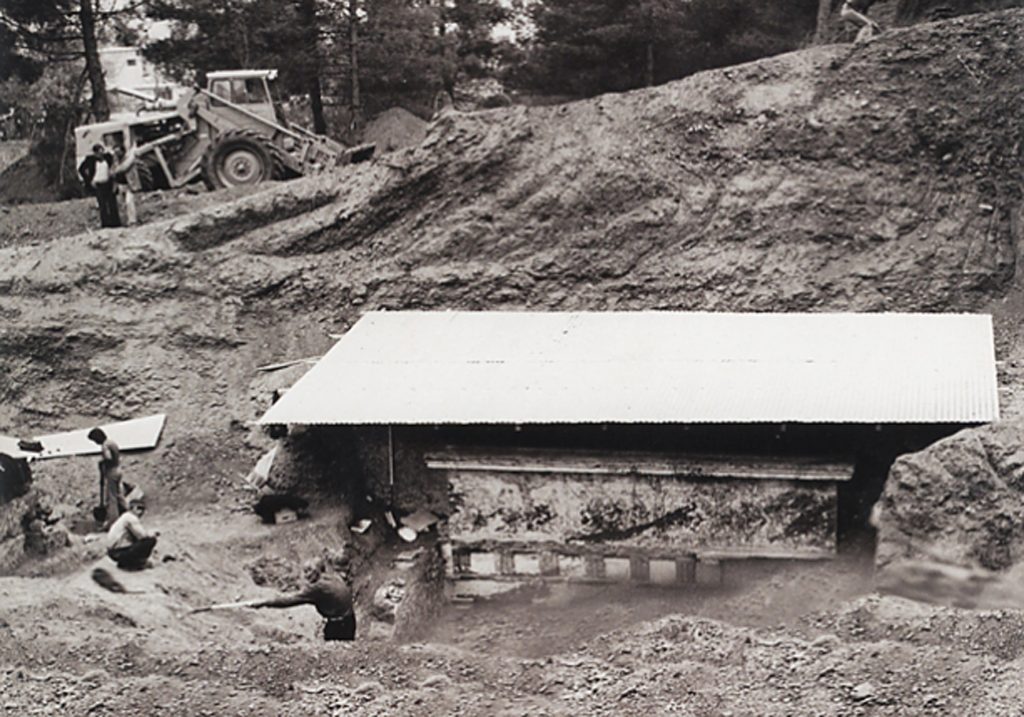

Tomb II emerging from the earth

What finally emerged from beneath a great tumulus of soil was the ‘archaeological find of the century’, rivalling Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings and Heinrich Schliemann’s excavations at ‘Troy.’ After a century of barren digs in the hills backdropping the Thermaic Gulf southwest of Thessalonica, the ‘lost’ nation of ancient Macedon was finally being unearthed.

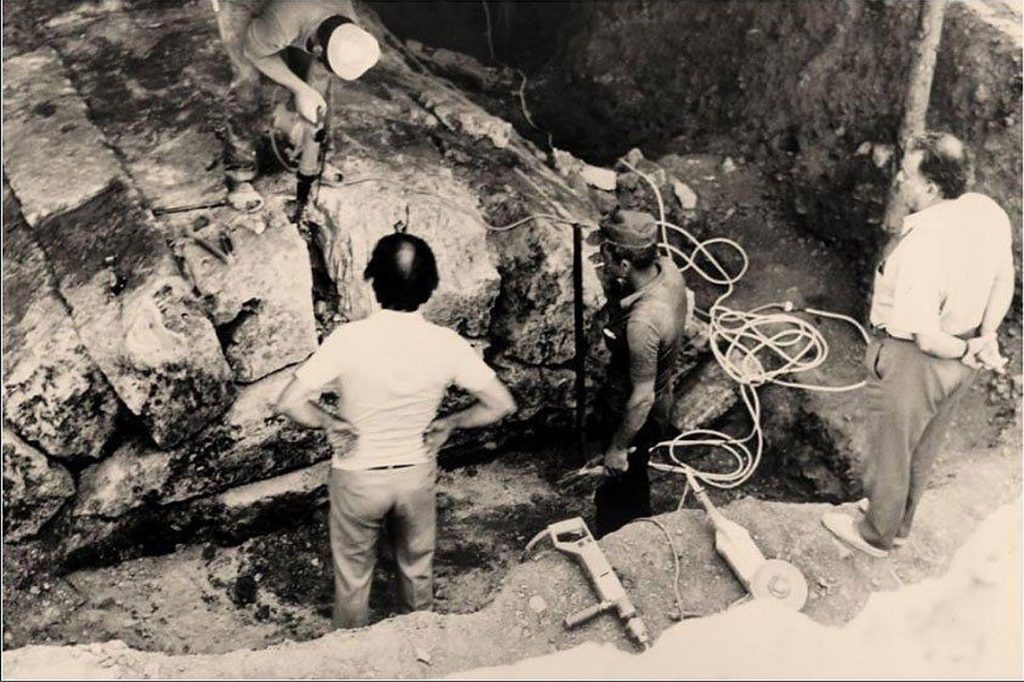

The removal of the keystone to enter Tomb II

Inside the main chamber of the barrel-vaulted structure known as ‘Tomb II’ lay gold and silver artefacts, and exquisitely worked weapons and armour accompanied by invaluable grave goods which suggested the presence of royalty. Within a stone sarcophagus sat a never-before-seen gold chest containing carefully cremated bones wrapped in remnants of purple fabric. In a further gold ossuary in the antechamber and similarly wrapped in a textile, were the cremated bones of a female, surely the dead king’s wife, arranged with a beautiful diadem of gold. A second unlooted vaulted structure, ‘Tomb III’ was unearthed the following year containing the bones of an adolescent, probably a boy, buried with the wealth of a ‘prince’.

The artefacts within were broadly dated to the mid-to-late fourth century BC (350s to 310 BC) and stylistically corroborated by pottery, metal artefacts and the evolving tomb design itself. Intriguingly, these years spanned the reigns of Philip II and his son Alexander the Great. The unique ‘Vergina Sun’ or ‘Star’ design of the royal clan of Macedon was embossed on the lids of the two gold chests holding the cremated bones.

The gold chest of ‘larnax’ holding the male bones in the main chamber of Tomb II, with the royal ‘Vergina Sun’ or ‘Star’ symbol

In October 336 BC, statues of the twelve Olympian Gods were paraded through Aegae, the ancient capital of Macedon. Following them was a thirteenth, a statue of King Philip II who was deifying himself in front of the Greek world. Moments later Philip was stabbed to death; it was a world-shaking event that heralded in the reign of his son, Alexander the Great. Equally driven by his heroic lineage, Alexander conquered the Persian Empire in eleven years but died mysteriously in Babylon. Either side of his reign, his father and family were buried at Aegae with lavish ceremonies, but the location of the city was lost.

Andronikos proposed Tomb II could be nothing but the resting pace of King Philip II of Macedon who was assassinated at Aegae, the burial ground of its kings, while some commentators believed the adolescent in Tomb III was Alexander’s murdered teenage son. Along with an earlier looted cist tomb and the adjacent ruins of a shrine, the grouping soon became known as the ‘cluster of Philip II’. In November 1977, the exalted excavator had hastily convened a press conference and informed the Prime Minister of Greece, oblivious to the political backlash his identity claim would encounter in the decades that followed.

A model of the shrine and tombs under the Great Tumulus at Vergina

Why the Tombs Vanished from History

The political capital of Macedon was moved from Aegae to Pella a century before Philip’s reign. Alexander died in Babylon in 323 BC, his thirty-third year, and his embalmed corpse was taken to Egypt where it remained well into the Roman Principate before vanishing. The failure to bury him in the traditional cemetery at Aegae invoked an ancient prophesy that the nation was destined to fall. The infighting of Alexander’s generals, who proclaimed themselves kings across the newly-conquered Graeco-Persian world, saw the empire fragment into Successor Kingdoms and there followed generations of internecine war when Macedon was itself divided. The prophesy was fulfilled.

In the 270s BC, two generations later, invading Gallic Celts ransacked the old cemetery at Aegae. When the danger had passed, the still-unlooted royal tombs were buried under a great earthen to protect them from further looting by an unnamed monarch.

A century on, when Rome defeated Macedon at the battle of Pydna in 168 BC, both Aegae and Pella were partially destroyed. A landslide covered much of what remained at Aegae in the first century AD, and as Rome’s influence expanded East, the importance of the cities diminished. When Rome’s empire was finally overrun, the name of the fallen-stone city survived in oral legend only. What was likely an earthquake caused the collapse of the top of the earthen tumulus and shattered doors in the tombs below, but the sturdy stone structure remained hidden under the occupied landscape for the next two thousand years.

Rediscovering the Ancient Kingdom

Modern excavations started in occupied Greece in 1855 in what was still part of the Ottoman Empire, but nothing more than ransacked tombs were found. However, the intriguing scale of the stone foundations suggested a substantial city once stood in the hills overlooking the Thermaic Gulf southwest of Thessalonica, the heartland of ancient Macedon.

Malarial marshlands hampered excavations and Greek refugees who had been resettled there from Turkish Anatolia after the Graeco-Turkish War knew nothing of its history. They used the ancient fallen stones from the anonymous ruins to build houses at the modern village of Vergina, named after a queen of legend.

In 1968 English historian Nicholas Hammond proposed the ‘heretical’ idea that the ruins at Vergina actually sat on the site of ancient Aegae. Few credited his theory; the belief prevailed that this was either the lost city of Valla, or a summer palace of unknown royalty.

In 1976 Professor Andronikos and team finally excavated the ancient necropolis where graves had been overturned and tombstones smashed in antiquity. This correlated strongly with the ancient texts claiming Celts had plundered the cemetery at Aegae; the burial ground of the nation’s kings had finally been found.

But an ‘unfortunate symmetry’ obscured the background to the double burial in Tomb II, says London-based historian David Grant who collaborated with the scientists studying the skeletal remains. This led to a ‘battle of the bones’ among historians, causing a rift which divided the academic community ‘obsessed’ on proving their identities.

The Tomb II occupants could either be Alexander’s father Philip II and his final teenage wife Cleopatra, as Andronikos believed, or Philip’s half-witted son Arrhidaeus who was executed twenty years later when of similar age with an equally young bride. Questions of ritual or forced suicide raised their head, because kings and queens rarely died together.

Philip II was a national hero who befitted such a tomb and he had seven wives we know of. But Grant’s research points out the elephant in the room: none of the ancient sources mention any women being buried with Philip at Aegae. What superficially appears to be a two-phase construction of Tomb II, plus the different cremation conditions the female bones underwent, suggest she was buried later than the male in the still-empty or incomplete second chamber.

On the other hand, Arrhidaeus and his young bride Adea-Eurydice were executed together by Alexander’s mother Olympias when she regained political control of the state capital. This ‘double assassination’ explains the ‘double burial’ given to them after Olympias was herself executed, the opposing ‘team’ of scholars argued.

When Alexander the Great died in Babylon in 323 BC, his royal regalia, including his cloak, sceptre and ceremonial weapons were passed to the newly crowned ‘King Philip III Arrhidaeus’ and escorted with him and Adea-Eurydice back to Macedon. So, they further proposed, the artefacts in Tomb II could be the very weapons of Alexander, explaining the grandeur buried with the half-wit king.

Why Philip and Alexander remain Greek national treasures

Philip II was the twenty-fourth monarch of a royal line stretching back, court propaganda claimed, to Olympic Gods and heroes. He was the first king to unite ancient Macedon and treble the land mass under its control into the first ‘European Empire’. His military reforms and statecraft brought Greece to its knees, enabling his son, Alexander the Great, to conquer the Persian Empire. Philip was a cultured cunning diplomat whose polygamous court hosted seven wives.

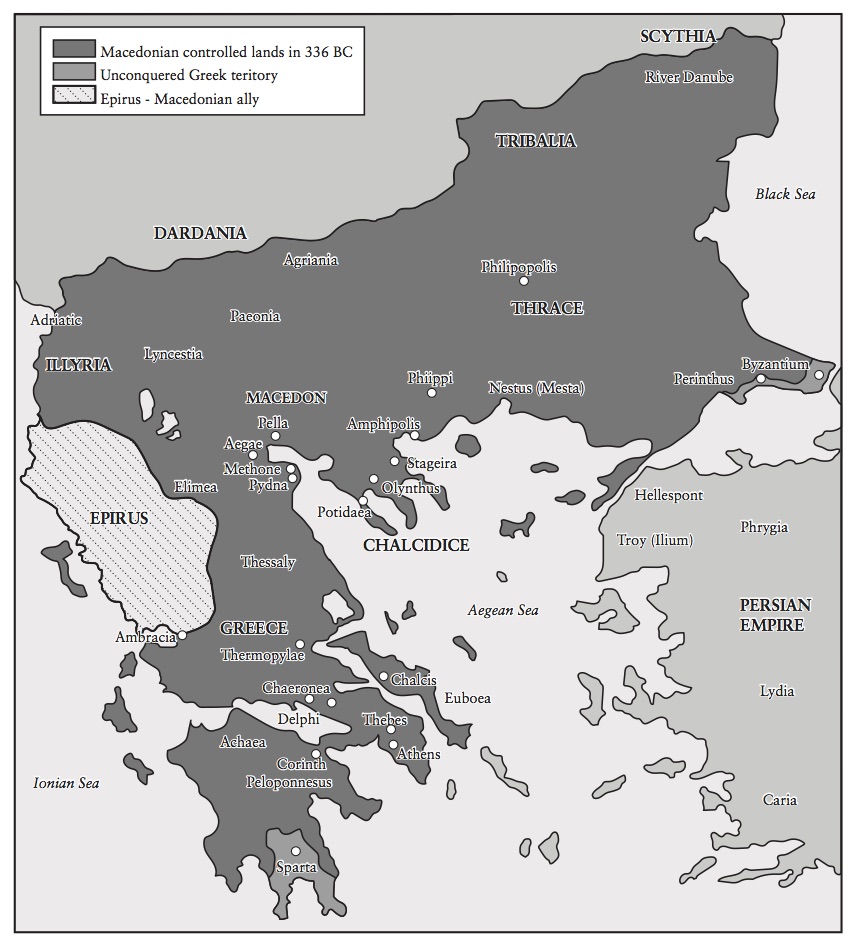

Lands controlled by Macedon at the end of Philip’s reign in 336 BC

Modern Greece reveres Philip and Alexander as national treasures. Yet this enduring adoration has always been something of a paradox: Philip and his son smashed Greek power at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, thereby ending one-hundred-and-seventy years of democracy that would disappear from Athens for the next two millennia. It also marked the end of the ‘Classical Age’ of Greece. Moreover, contemporary Athenian orators like Demosthenes proclaimed that the ‘Macedonians did not even make good slaves.’ However, the reigns of Philip and Alexander paved the way for the Hellenistic Era which spread Hellenic culture throughout the Graeco-Persian world; this is the true achievement still embraced today.

The Mystery of the Scythian ‘Amazon’

At the centre of the Vergina tomb debate lay an ‘intruder’ weapon of great controversy: a gold-plated Scythian bow-and-arrow quiver like those carried by Scythian archers; the Tomb II female appears to have been a renowned ‘warrioress’. Grave digs in Russia and Ukraine have proven the existence of female warriors in this period, and so the excavator postulated that the Tomb II woman must have had ‘Amazonian leanings’. Here Andronikos was referring to the matriarchal race who featured prominently in ancient Greek legend and whose latter-day descendants were said to be Scythian female mounted archers.

The gold quiver and greaves of the female in Tomb II stacked against the chamber-dividing door.

Others were more skeptical of the connection. ‘Weapons were for men what jewels were for women,’ reads a plaque in the subterranean Vergina Museum. Because of this arguably archaeological “gender bias’, many commentators believed that the antechamber weapons belonged to the man next door, as their upright position against the dividing door might indicate. The tomb conundrum remained unsolved.

One early hypothesis of the identity of the Tomb II female favoured a presumed daughter of King Atheas of the Danubian Scythians who at one stage planned an alliance with the Macedonian king by adopting Philip as his heir, despite having a son. The once-friendly relationship with Atheas broke down, but scholars conjectured that a daughter, given freely or taken with the 20,000 captive women in the wake of the briefly-enjoyed Macedonian victory, could then have become Philip’s concubine or possibly his seventh wife of what would then be eight in total.

A female Scythian archer with hip-slung bow-and-arrow quiver from an Attica plate dated 520-500 BC.

Elegant as the hypothesis sounds, no daughter is ever mentioned in the ancient texts. Adopting Philip was rather a strange move if Atheas had a daughter, as the established method of forging an alliance with Macedon was to marry a young daughter to Philip at his polygamous court.

The Scythian daughter theory encountered more hurdles: Herodotus’ colourful description of the Scythian pre-burial practice involved slitting open the belly of the deceased, cleaning it out and filling it with aromatic substances, after which the corpse was covered in wax before carting around for display to the tribe. In contrast, the Tomb II woman was cremated soon after death with no feminine adornments. Scythian female burials, however, were usually accompanied by jewellery: glass beads, earrings and necklaces of pearls, topaz, agate and amber, as well bronze mirrors and distinctive ornate bracelets. The Vergina mystery deepened.

The ‘battle of the bones’ on tomb identities continued for three decades. Arguments revolved around wounds evident or invisible on the Tomb II male bones when compared to the battle wounds Philip reportedly suffered. Wall paintings, entrance frescos of a hunting scene and even condiment pots found on the floor were heralded up as dating witnesses. But it was always debatable whether the twenty years between the death of Philip II and his half-witted son Arrhidaeus could be discerned by interrogating the subtleties of relics this way.

The façade of Tomb II with the hunting-scene friese painted above the entrance.

Recurring questions filled academic papers: ‘did vaulted roofs exist in Greece in Philip’s reign? Was the hunting fresco, with its controversial depiction of lions in the quarry, inspired by the Persian game parks Alexander and his men witnessed on his campaign in Asia? All the ‘proofs’ for and against were argued both ways with equal dexterity.

By 2009, the ‘battle of the bones’ reached a stalemate when academics arguing the tomb identities ran out of debating ammunition. The American Journal of Archaeology even called for a moratorium on ‘Vergina papers’ until new evidence came to light, noting that the polarised positions of archaeologists dated back to political rivalries from decades earlier.

The mysteries and controversies of the royal tombs remained as profound as ever: would there ever be a resolution?

The entrance to the subterranean Archaeological Museum of Vergina.

Read PART 2 of the Vergina tomb story Here.

Unearthing the Family of Alexander the Great, the Remarkable Discovery of the Royal Tombs of Macedon by David Grant is available from Amazon and all major online book retailers.

Potentially a missing part of the Antikythera mechanism, an ancient Greek device designed to calculate astronomical positions and often considered the world’s first computer, has been found on the Aegean seabed. The section was discovered at the same wreck site where the original 2,200 year old mechanism was first located in 1901. Researchers were elated to retrieve artifacts that had survived not only the passage of time, but also the destruction havocked by looters and Jacques Cousteau. (Indeed, in 1976, the famous French explorer accidentally destroyed much of what remained of the ship’s hull.)

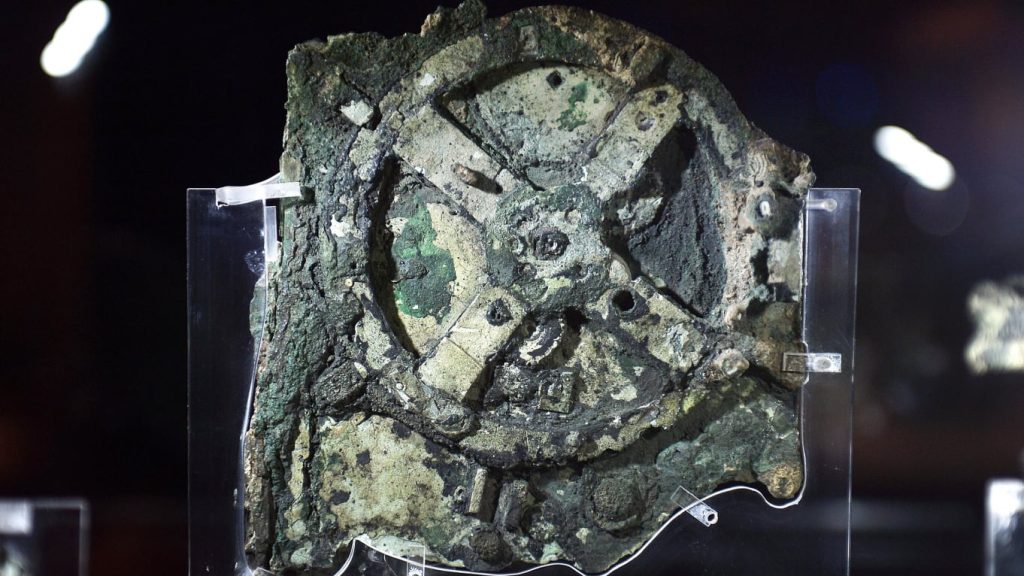

Antikythera Mechanism, Louisa Gouliamaki/Getty

The Antikythera Mechanism was initially lost when the cargo boat that it was on was shipwrecked off the coast of a small Greek Island between Kythera and Crete called Antikythera (which is why it has been named the Antikythera Mechanism).

When the Mechanism was first discovered, Greek sponge divers brought it to archaeologist Valerios Stais at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, who had no idea what they had discovered. Fortunately Spyridon Stais, Stais’ cousin and a former mathematician, was able to recognize the gears in the mechanism. With the development of advanced x-ray technology and plentiful collaboration (from Cousteau to modern historians of science like Alexander Jones), it was eventually identified to be a technologically advanced calculator.

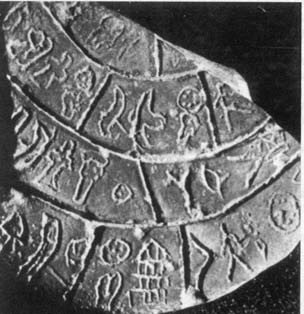

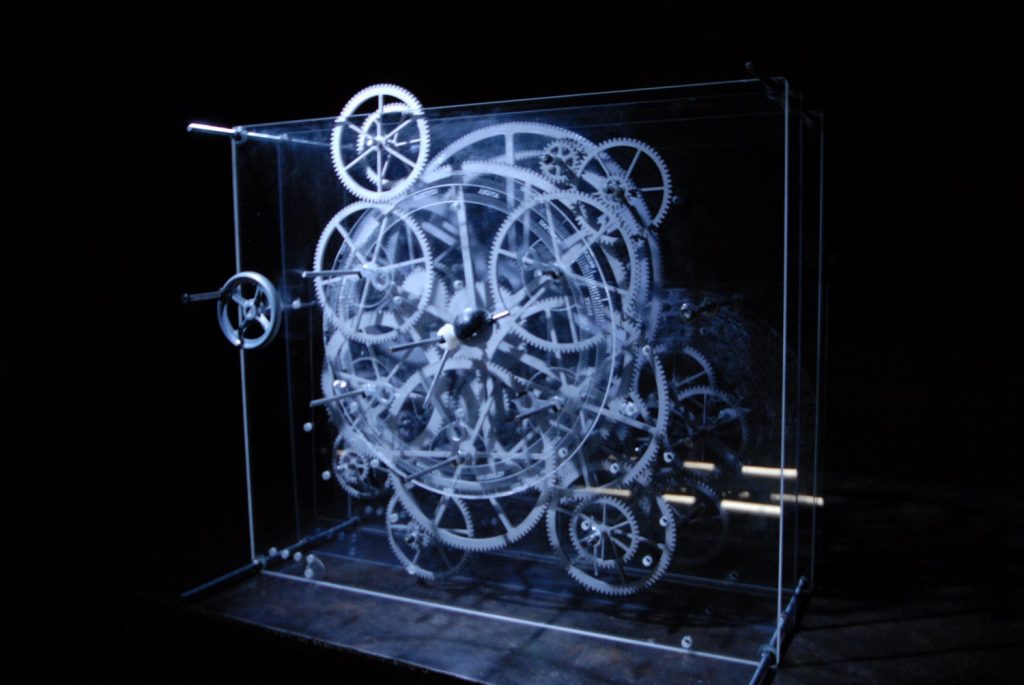

The gears of The Antikythera mechanism

For those who want a quick recap on the abilities of the Antikythera Mechanism, the second century BCE invention could calculate the movements of the sun and moon, predict eclipses and equinoxes, track movements of constellations and planets… as well as do basic math!

Not only that, but the Greek (possibly from the Island of Rhodes) creation also contains over thirty hand-worked cogs, dozens more than the average luxury Swiss watch.

Almost 50 years after Cousteau’s underwater research, a new team of archeologists excavated the site, finding hundreds of previously undiscovered artifacts, such as statues, coins, furniture, even a sarcophagus lid.

Last year they found an encrusted corroded disk about 8 cm in diameter… and recently it was revealed that the disk has an engraving of the zodiac sign Taurus the bull, which was discovered through x-ray analysis.

Discovery of a missing piece of Antikythera Mechanism on the Aegean sea floor Brett Seymour / EUA/ARGO

While archaeologists still do not know exactly what this new piece is, there are theories that it could be part of the original Antikythera Mechanism or a section of a second similar device. The reason for this thinking is the presence of the bull engraving, which could have been for the prediction of the constellation of Taurus.

Of course, it will be impossible to know for sure whether this discovery is a piece of the world’s oldest analog computer… or a remarkable discovery on its own terms. Either way the continued exploration and research has drawn attention to the existence of this ancient ‘calculator’ as well as to the field of archeology itself.