Written by Michael Dehoyos, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

All cultures throughout the world have their own legendary creatures. These creatures were believed to be extraordinary animals or hybrids who possessed special abilities or attributes. While some were believed to be highly intelligent, others were known for being dangerous and powerful. Here we explore the top five most powerful mythical creatures.

1. Chimera

The Chimera originates from Greek mythology and was thought to be a female monster from Asia Minor. The two-headed chimera was in fact comprised of three animals: she had a lion’s head and body, upon which sat a second head – that of a goat – and had a snake for its tail. A fire-breathing monster, it was in fact the goat head which breathed out fire.

Although the chimera was believed to be almost invincible, according to legend, Bellerophon was able to slay her by driving a lead-tipped sword into her flame-covered mouth, making her choke on the molten metal. Since then, the term chimera has often been used in mythology to describe creatures which are made up of various parts that come from different animals.

2. Basilisk

Considered by many to be one of the deadliest mythological creatures, the basilisk or cockatrice was believed to be born from a serpent’s egg which had been incubated by a cock, or rooster. The resulting creature was therefore half-bird and half-snake.

Often referred to as the king of serpents, the basilisk was believed to be extremely hostile towards all humans. It was said to have the power to kill a person simply with one glance. In addition to its powerful killing glance, its venom was also claimed to be extremely toxic and deadly.

3. Dragons

“Probably one of the more well-known mythical creatures, dragons are a common feature across many different cultures. There are many descriptions of a range of dragon types throughout folklore, including the Hydria, Dragonnet and African dragon. It was believed that the different names of the dragons related to different aspects of their characteristics,” according to Ramon Richards, a journalist at Britstudent and PhDKingdom.

In Western cultures, dragons were often depicted as four-legged reptiles that could fly and breathe out deadly fire. In Eastern cultures, however, they were more commonly described as highly-intelligent, four-legged serpents.

4. Kraken

The Kraken is a mythological creature from Scandinavian mythology. Most often described as gigantic squid or octopus-shaped sea monster, the Kraken was believed to be found off the coasts of Greenland and Norway. According to various myths, the Kraken was extremely powerful. In fact, it was believed that it was powerful enough to create whirlpools which could bring down entire ships. The Kraken itself was also reported to attack and destroy ships.

“There is some suggestion that the myth of the Kraken could have arisen as a result of giant squids, which could grow to be up to 18 meters long. These rare creatures were very rarely seen by humans, but it is likely that the few sightings were enough to inspire the mythical creature we know as the Kraken,” Alexandria Allen, a history writer at 1Day2Write and Writemyx, said in an interview.

5. Sirens

Sirens were considered dangerous and beautiful creatures. Also known as mermaids, sirens had an upper body which resembled that of a human female, whilst their lower half was that of a fish. Sirens appear in folklore from many countries worldwide. Most often they were deemed to be a sign of misfortune.

It was believed that they possessed beautiful, enchanting voices which, along with their physical beauty, were used to lure sailors to their deaths. Sirens were most often associated with drownings and shipwrecks, whilst their male counterparts (known as mermen) were believed to have the power to summon storms and even sink ships.

Conclusion

There are countless other mythical creatures to be found in folklore and tales from cultures all around the world. While not all mythical creatures were believed to be dangerous, all were fantastical. As a result, these creatures have managed to remain part of our modern cultures vis-a-vis popular literature, films and television. Clearly, these powerful mythical creatures continue to fascinate and capture our imagination.

By Benjamin Welton

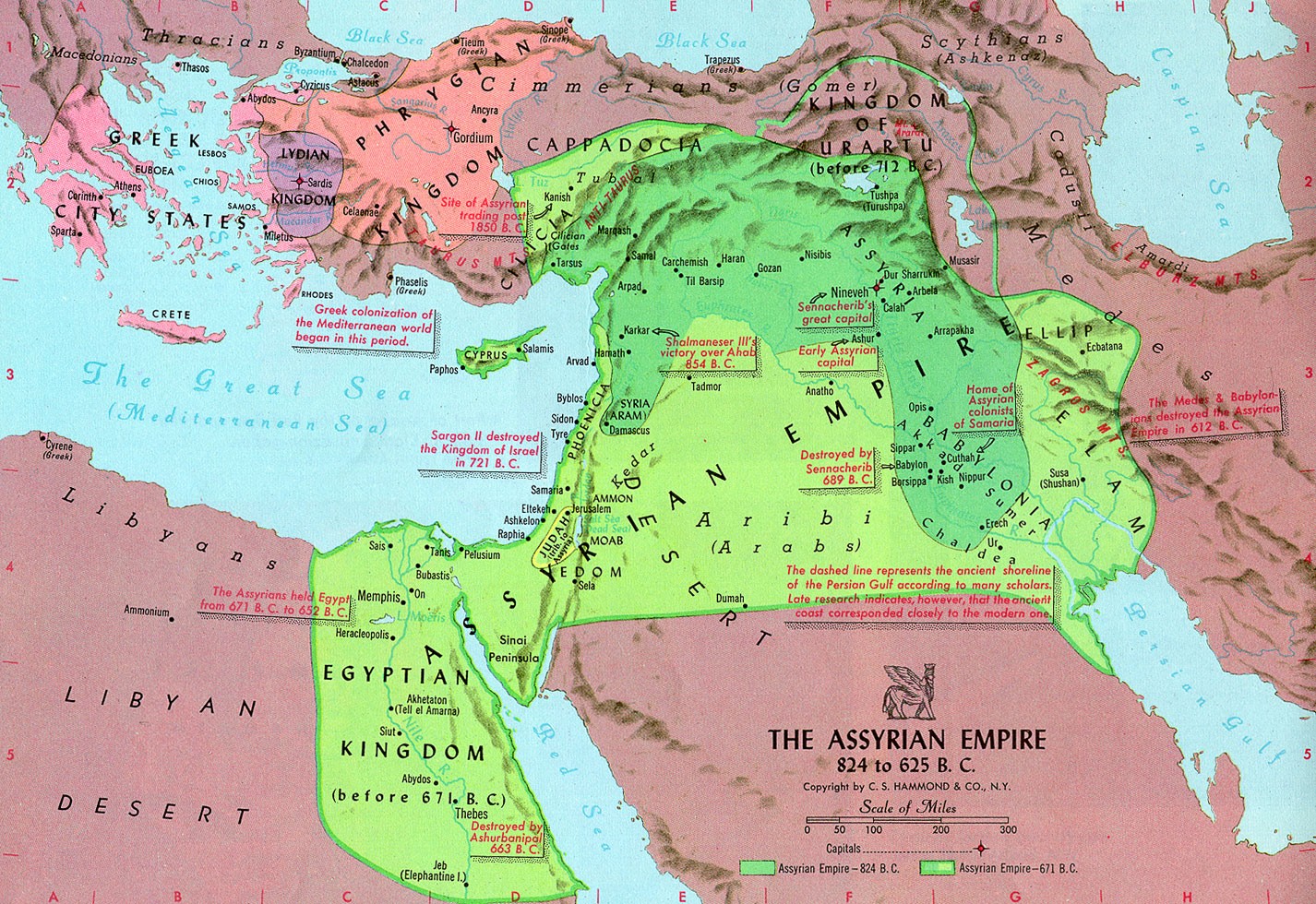

There is a story (most likely untrue) that begins with a team of European archaeologists overseeing a dig in northern Iraq. They are somewhere near Mosul, the current stronghold of the Sunni extremist group ISIS in Iraq. They have come to this part of the world in order to excavate relics from the bygone empire of Assyria – a brutal, but effective state composed of warrior kings and their dreaded armies.

For the archaeologists themselves, the importance of Assyria is twofold: first, the Assyrian state ruled for a time the world’s largest and most powerful empire. They reigned by the point of the sword, and tales of their shocking inhumanity on their vanquished foes still have the ability to terrify even the sternest of imaginations.

Secondly, the Assyrians, and the empire they created, were one of the great foes of both the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah. As such, Assyrian villains are sprinkled throughout the Old Testament. Indeed, the Book of Nahum details the fall of the Assyrian capital of Nineveh, the most reviled fortress city in the ancient Near East. For the Jews, the early prophecy that Nineveh, the:

Besides this biblical prophecy, our European archaeologists would have undoubtedly been aware of the fact that Jesus Christ spoke the Aramaic language, the lingua franca of the Near East. This was a tongue which had been used by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, along with the older Akkadian language, as a tool for imperial unification in the realms of trade and government.

While the European archaeologists rock themselves to sleep with ideas of discovering some proof of the historical Jesus, or maybe uncovering something that had been lost to recorded history for thousands of years, their local workers, most of whom are pious Muslims, pray for the expedition to not find anything. After all, it would not be wise to upset the old gods, which to them represent powerful demons.

But in the morning, underneath the hot, arid sun of old Assyria, the workers stumble upon something large.

More digging reveals wings.

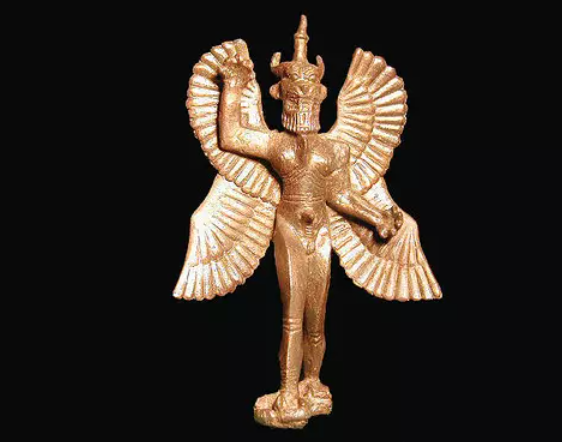

My God, they’ve uncovered a statue of Lamassu, a protective deity. They have awakened the old gods. They flee in terror.

Or so the story goes…

But you see, the old gods of Mesopotamia are not to be taken lightly. According to the famous British Egyptologist Sir E.A. Wallis Budge’s book Amulets and Superstitions, the:

“literature of the Sumerian and Babylonians…proves that the people who occupied Mesopotamia from about 3000 BC downwards attached very great importance to magic in all its branches, and that they availed themselves of the services of the magician on every possible occasion.”

A large part of this ancient magic involved protection against the many demons who plagued them, from the spirits of the angry dead to the archfiend Lamashtu, the female demon who lived in the mountains and cane brakes and preyed upon pregnant women and children.

Again, Budge was succinct when he stated that from the earliest moments of recorded time, the people of Mesopotamia, “were in perpetual fear of the attacks of hosts of hostile and evil spirits which lost no opportunity of attempting to do them harm.”

In order to understand Assyrian demonology, one must appreciate the peoples who came before, for the Assyrian religion, and even the Assyrian way of war, was inherited (although the Assyrians did add excessive cruelty, so they can be credited with at least one innovation).

It started in Sumer, the first great civilization in Mesopotamia (modern day southern Iraq). They created not only writing, but also a whole pantheon that would serve their successors up until the coming of Alexander the Great. The Sumerian gods included: Enlil, the Lord of the Storm and the heroic head of the pantheon, the air goddess Ninlil, and Inanna, the female god of fertility, war, and wisdom.

The Sumerians built impressive ziggurats, or stepped temples, for the purposes of worshipping these gods. Cities such as Uruk, Nippur, and Eridu (which the Sumerians considered ancient – thus making it arguably the world’s oldest city) served as commercial and religious centers.

[Side Note: This text, along with the Neo-Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, were both re-discovered in 1849 by the British archaeologist Sir Austen Henry Layard at the Royal Library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh. Ashurbanipal was the last great king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.]

Likewise, dark, malevolent gods were present in their cosmology… and none was more vile that Ereshkigal, the goddess of the underworld, or Irkalla. Along with Nergal, the plague god, Ereshkigal acted as the tyrant of Irkalla and was the chief judge of the dead.

The story of Inanna’s descent into the underworld provides a glimpse into Ereshkigal’s wickedness:

Naked and bowed low, Inanna entered the throne room.

Ereshkigal rose from her throne..

Inanna started toward the throne..

The Annuna, the judges of the underworld, surrounded her..

They passed judgment against her..

Then Ereshkigal fastened on Inanna the eye of death..

She spoke against her the word of wrath..

She uttered against her the cry of guilt..

She struck her..

Inanna was turned into a corpse,.

A piece of rotting meat,.

And was hung from a hook on the wall… .

Inanna, who is more commonly known by her Akkadian name of Ishtar, manages to defeat the machinations of Ereshkigal and returns to the world of the living. For her pain, Ereshkigal threatens Inanna with a show of her power, to send her army of the dead above ground as a moving pestilence bent upon destruction.

To their enemies, the Assyrian hordes must have seemed like Ereshkigal’s army of the ravenous dead; they were a nation of fearsome warriors. And although their rise was slow and their fall spectacular, the Assyrians left an indelible mark on the regions that they conquered… More than anything else, they spread fear.

Evidence of this can be found in the fact that the early Jews turned the Assyrian gods into demons. Astarte, the Assyrian version of Ishtar, became Astaroth, the Crowned Prince of Hell. Similarly, the Assyrian Bel, who would be called Baal by the Canaanites, would become Beelzebub, the demonic “Lord of the Flies.”

(Again, most Assyrian demons were present beforehand, in the mythos of earlier Mesopotamian societies. These include the Sumerian ekimmu, a type of vampiric ghost, or the Akkadian lilu and lili, who were male and female demons that more than likely served as the inspiration behind Lilith in the Old Testament. Demons that were specific to the Assyrians – or at least more often used by them – include Ilu Limnu, the “evil god” who is never given definite characteristics, and the gallu, or bull demon.)

In The Devils and Evil Spirits of Babylonia, the Assyriologist Reginald Campbell Thompson details the various “demons, ghouls, vampires, hobgoblins, ghosts” that cursed the regions around the Tigris and Euphrates… as well as the Babylonian and Assyrian incantations that were used against them.

According to Thompson, the Assyrians held a great fear of sorcerers, whom they called the “Raiser of the Departed”.

The most famous Assyrian wind spirit known widely today is Pazuzu, the son of the god Hanbi and the demon of the southwestern wind. With the body of a lion or dog, a scorpion’s tail, wings, talons, and a serpentine phallus, Pazuzu brought famine and locusts during the dry seasons. In an odd twist, Pazuzu was the rival of Lamashtu (the goddess who preyed on pregnant women and children), and as such, his image was often used to combat other demons.

Of course, Pazuzu’s notoriety is the result of William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist. Although the film is more obvious than the book in depicting the spirit of Pazuzu as a monstrosity haunting young Regan MacNeil (neither, however, directly state that the demon is indeed Pazuzu), the message is still clear. Blatty’s decision to make the chief evil in The Exorcist a pre-Christian, Assyrian demon is in keeping with the Western tradition of seeing all things Mesopotamian as depraved.

Furthermore, by beginning his novel, and thus the film, in northern Iraq, Blatty made the conscious decision to play upon his audience’s preconceived notions…

Namely, that the land of the old Assyrians is indeed a land of demons.

Let’s face it… Monsters are cool. Whether you are 5 or 50, they can enthrall, enchant and terrify!

But… why? Seriously, what causes humans all over the globe, all throughout history to invent these creative creatures that can scare us so?

And, more specific to the Greco-Roman world, what is it about our classical monsters that still manage to capture the imagination…. thousands of years later?

This is exactly what Dr. Liz Gloyn, Reader of Classics at the University of London and one our Symposium speakers delves into in her most recent book, “Tracking Classical Monsters in Popular Culture“.

She looks at how monsters can been seen throughout the modern era and their enormous adaptability in finding places to dwell in popular culture without sacrificing their connection to the ancient world.

Yes, dear reader, those monsters are still hiding among us! But where?

Check out Dr. Gloyn’s fantastic book to find out.

From the siren to the centaur, all monster lovers will find something to enjoy in this stimulating and accessible book:

Check out these Great Reviews:

“In this remarkable volume, Liz Gloyn is a new Ariadne who tosses Theseus out of the labyrinth and instead offers the Minotaur a dazzling story-thread. Gloyn’s compelling exploration gives voice to the classical monsters of popular culture and uncovers their powerful impact on society today.” – Monica S. Cyrino, Professor of Classics, University of New Mexico, USA,

“Informed by expert knowledge of the field and presenting a highly thoughtful and engaging approach to the material, this book creates a space that enables classical monsters to push the ubiquitous – and usually male – hero off the pedestal for a moment and be appreciated in their own right.” – Michael Williams, Professor of Film, University of Southampton, UK,

“This book will appeal to anyone with an interest in monsters and their place in popular culture.” – Salon Futura

Ask the Monster Expert Yourself!

Dr. Liz Gloyn will be speaking LIVE at our Classical Wisdom Symposium both in her own presentation on Monsters, Power And Control and in the panel discussion.

In fact, you can read her book and ask her questions about it directly! Make sure to check out all the details of our Symposium below!

By Katherine Smyth, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

If you think you know the story of Circe, the witch of Aeaea and the seducer of the hero Odysseus, think again. There’s more to her story than is widely publicized or acknowledged, but to understand how Circe became one of ancient Greek mythology’s most notorious women you have to go back to the beginning of time.

Time before men

Back before men were even a twinkle in Prometheus’ eye, Circe was born to Helios, a son of the Titans Hyperion and Theia, and brother to the goddesses Selene and Eos. She is also cousin to Zeus, the King of the Olympians. So you could say that Circe was born into quite a noble family. A granddaughter of at least two Titans and related to the sun, moon, and dawn, big things should have been laid out for her from birth.

Except, that’s where her ancestry gets indistinguishable and a little problematic. One possibility is that she was a daughter of Hecate, an ancient deity that pre-dates the Olympians and whom Zeus honored above all, at least according to Hesiod.

Circe’s other matrilineal probability is Perse, an Oceanid nymph and one of several thousand daughters by the Titans Oceanus and Tethys. Perse is also the mother of Aeetes, keeper of the Golden Fleece; Perses who was killed by his niece Medea; and Pasiphae the Queen of Crete. What makes her lineage a bit tangled is that Perse can also be closely identified with Hecate, a virgin goddess who had no regular consort. Hecate is also listed in some traditions as the mother of Scylla, who you’ll be introduced to shortly.

Les Oceanides Les Naiades de la mer. Gustave Doré, 1860s

Here enters Circe, the granddaughter of four Titans, niece to the moon and sunrise, blessed by the golden rays of her father, but lacking all the enticements and goddess-given beauties of her nymph mother. Yes, according to myth, when Circe was born she was not what was expected. Instead of being attractive with willowy limbs and a melodic voice, like the other nymphs, Circe lacked all the usual charms of a seductress. Instead, she was short, dark, and sounded like a squawking bird. This is where her name stems from, specifically the Latinized form of Greek Κιρκη (Kirke), which possibly meant “bird”.

The making of a witch

Growing up, Circe was all too aware of her shortcomings. Unlike her sister Pasiphae, she would not be married off to a mortal to rule over humans and bear mythological beasties (see my previous article on the Minotaur). Also, unlike her brothers Aeëtes and Perses, she was denied a kingdom of her own. So, she stayed with the throng of Titans and Olympians and kept to herself.

John William Waterhouse’s Sketch of Circe (c. 1911–1914)

It was during this isolation that her gifts were developed and honed. Whether it was due in part to her maternal parentage, or whether it was her fate, Circe’s magical abilities manifested into both potion making and spell casting. Circe quickly gained a reputation for trickery, being ill tempered, and adept at casting spells on those who ridiculed and mocked her. Would-be lovers who spurned her, or essentially anyone who showed her any disrespect would find themselves transformed into an animal without the slightest effort on her behalf.

According to some versions of her story, it is this crafting of the supernatural that ultimately led to her exile on the remote, and fictitious, island of Aeaea – thought to be located off the southern coastline of Italy, about 100 kilometers from Rome. She was sentenced to an eternity on the island as punishment for practicing witchcraft on her fellow nymph, Scylla. Circe had fallen in love with Glaucus, a sea-god, who as the Fates would have it became besotted with Scylla. When Circe’s advances and attempts at seduction failed miserably, she became incensed and in a jealous rage, Circe poisoned the water where Scylla bathed. As a result, the hideous monster was born and Circe’s fate was sealed: life-long banishment from her immortal home and family.

Circe and Scylla in John William Waterhouse’s Circe Invidiosa (1892)

However, it’s here on the island of Aeaea that Circe’s greatest claim to fame is formed. Odysseus, King of Ithaca, war hero of the Iliad and doomed sea captain was guided to Circe’s island as part of his journey back home. Fortunately for him, Hermes told him what to expect, and how to elude her spells and potions. So, when Odysseus landed on the shores of Aeaea, and half of his men met with the enchantress’ wrath, her immense powers were futile against him thanks to an herb called moly.

A different fate perhaps?

Angelica Kauffman’s painting of Circe enticing Odysseus (1786)

Instead of harming her for attacking his men, Circe and Odysseus’ relationship took a different turn. Once Circe realized that she was unable to defend herself against Odysseus’ advances, she instead became his lover for the rest of his time on Aeaea. Now, some would say that bedding Odysseus was the act of a woman whose plans been defeated, that when she knew she could not turn him into an animal – as she had done to so many other mortals and fools alike – she instead used sex to her advantage. But is this truly the case, or did she admire and deeply care for him as a result of his intellect and wit?

This same story that paints her as being malicious glosses over the fact that she opened her home to a host of rude and selfish men. That for a year Circe fed, housed, and clothed them. Circe offered hospitality to those who had sought to violate, harm and destroy her, and the parallel between her generosity and that of Penelope’s should be remembered. What was Odysseus’ response to his wife’s hospitality towards ‘the Suitors’? He massacred them, as a victorious and righteous hero and husband. Yet Circe is condemned for protecting herself.

Odysseus’ killing of the suitors

During their union, Circe and Odysseus brought about the creation of three sons; Agrius, Latinus, and Telegonus, all of whom would become famous like their father. However, it is Telegonus, the youngest, who would become the ill-fated offspring that kills his father. Ironic as it fulfilled Odysseus’ fate, a foreshadowed story that he’d been warned of years before. Divine punishment perhaps, for the wrongs the hero committed?

As Odysseus’ time on Aeaea came to an end, it was Circe who gave him valuable insight on how to sail safely home from Aeaea, and how to avoid the island of the Sirens, along with steering clear of both Scylla and Charybdis. Circe also gave Odysseus information on how to avoid punishment should they land on Thrinakia, the home of her grandfather, Hyperion’s cattle. Unfortunately for Odysseus, his crew ignored Circe’s advice and their destruction was assured as retribution, all saving the captain.

Although Odysseus survived the punishment that killed his men, the story of Circe and Odysseus does come to a sticky end. Upon discovering who his father was, Circe sent her youngest son to find his father before returning to her. Unfortunately, that’s where the Fates stepped in, and through a terrible accident, Odysseus was slain. As foretold, Odysseus was killed by his son, just not the one he expected. Where he feared it would be his beloved son Telemachus, it was instead Telegonus, the boy he never met who sought only his father’s love and acceptance. The next time Circe would see her son was when he returned to Aeaea with Telemachus, Penelope, and Odysseus’ body.

Odysseus and Penelope. Painting by Francesco Primaticcio (1504-1570). Photo: Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio.

Hesiod’s Theogony indicates how Circe’s fate may have played out from this point. Upon the return of Telegonus, they bury Odysseus’ body and then Circe makes the other three into immortals. Madeleine Miller, the author of Circe, expands on this with another possibility that Penelope and Telegonus become lovers and remain on Aeaea as immortals. After a lifetime or so together Circe and Telemachus give up their immortality to die, whereupon the story is completed and fades into time immemorial.

Circe in History

Since the days of ancient Greece, Circe’s name has been synonymous with witchcraft, seduction, and deception. She’s been depicted in paintings tempting Odysseus, casting spells over his men, and practicing her dark arts to lure wayward men and punish them.

Artists like Frederick S. Church have portrayed her in gentler tones, whilst John William Waterhouse’s Sketch of Circe displays her intelligence, wit, and her animalistic companions. Are these the only artists to have presented her in art? No, Circe’s been popping up in paintings, drawings, and illuminations for hundreds, if not thousands of years. She’s been both muse and subject for many, but sadly she’s almost always seen as a villain.

Frederick S. Church’s painting of Circe

Was Circe really to blame?

This is popular opinion and aids the narrative that permeates much of classical mythology and history, and fulfills exactly what Steven Sora (The Triumph of the Sea Gods) and Sigmund Freud (the Madonna-whore complex) refer to in their works. It is the old trope of women interfering or causing good men to go bad, and Circe’s story is merely one such example.

But Circe is, at least, in fine company. She sits quite comfortably alongside the likes of Helen of Troy, Pasiphae, Clytemnestra, Hera, Hecate, and a host of other ladies who’ve all been labelled as troublesome. Perhaps it’s finally time to view Circe in another light, that of being considerate and generous, intelligent, clever, headstrong and independent.

By Katherine Smyth, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Down, down below the imperial Palace of Knossos, the capital of Crete and home to King Minos, legend has it that there lurks a mythical beast. A beast so terrible, so ferocious, that it could not be allowed to see the light of day. Contained within a maze, and fed by sacrificial rites, it is doomed to a storybook ending.

Minotaur bust, (National Archaeological Museum of Athens)

The Backstory to the Minotaur

The tale of the Minotaur has been popular throughout the ages; it dates back to Classical times and has a mythic base. Legend has it that the Minotaur was born as a result of Queen Pasiphae’s coupling with another mythological beast, the Cretan Bull. But, how did this happen?

Back in Crete’s early days, King Minos sought to assert his right to the throne over his brothers. As such, he prayed to the god Poseidon to send forth a magnificent bull, the Cretan Bull. Should the god grant this plea, Minos would sacrifice the bull in Poseidon’s honour in order that the deity would declare Minos’ right as ruler.

Pasiphaë and the Minotaur, Attic red-figure kylix found at Etruscan Vulci (Cabinet des Médailles, Paris)

But when Minos saw the bull and its magnificent breeding qualities, he refused to keep his end of the deal. Angered by this treachery, Poseidon asked the goddess Aphrodite to bewitch Minos’ wife, Queen Pasiphae, to fall in love with the bull. Consequently, the Queen gave birth to a child that was both human and bull-like in appearance.

How the Minotaur Got His Name

King Minos, ever the one to make the most of a sticky situation then decided that rather than face the humiliation of an unfaithful wife and an illegitimate offspring; he would name the beast after himself.

The name is translated from ancient Greek; Μῑνώταυρος, it is a combination of ‘Taurus’ (ταύρος in Ancient Greek) meaning bull, and ‘Minos’, or Μίνως in A.G. However, in Crete the beast was also known by the name of Asterion. This is the name of Minos’ foster-father and the first King of Crete.

The Minotaur in the Labyrinth, engraving of a 16th-century AD gem in the Medici Collection in the Palazzo Strozzi, Florence

After the Minotaur’s birth, the Queen attempted to nurse and raise him as a prince of Crete. Unfortunately, the beast developed an unnatural appetite that could only be satiated by human flesh. King Minos sought advice from the Oracle at Delphi, and upon his return, he had the craftsman Daedalus design and build a mighty cage that would contain the beast; the Labyrinth. There, near the Palace of Knossos, the Minotaur was incarcerated. He was fed on a strict diet of human sacrifices, which were supplied by the King of Athens as punishment for murdering Minos’ son, Androgeos.

The Death of the Minotaur

King Minos’ son, Androgeos, had entered the Panathenaic festival – an early form of the Olympics – and had won many events in the games. Jealous of the prince’s success, the people of Athens murdered him. Another version of Prince Androgeos’ demise holds King Aegeus responsible, as the King had sent the prince to kill the Cretan Bull, where it was now running amok in Marathon. Androgeos attempted to kill the bull, but was instead gored to death.

Enter the hero Theseus, son of King Aegeus, the ruler of Athens.

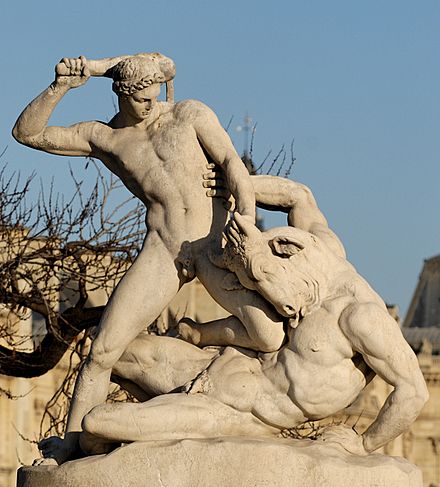

Theseus Fighting the Minotaur, 1826, by Jean-Etienne Ramey, marble, Tuileries Gardens, Paris

King Minos’ punishment to the people of Athens was brutal, every seven years Athenians were to select seven male youths and seven female youths who would be sent to Crete. There they would be expelled into the labyrinth and left to be hunted down by the Minotaur, who would kill and devour them one by one.

As the third sacrifice approached, some 21 years after the murder of Androgeos, Prince Theseus volunteered to end the debt by killing the monster. He sailed, with the 14 sacrificial youths, to Crete and presented himself to King Minos as part of the tribute. However, he caught the eye of King Minos’ daughter, Ariadne, who was instantly besotted with the hero. As the time of the sacrifice came, the prince and princess hatched a plot to ensure his safety – a length of twine that Theseus could unfurl to prevent getting lost in the Labyrinth.

Down into the dim and stench-laden labyrinth Theseus ventured, trailing the line as he went, hunting the monster that had eaten his fellow Athenians. Eventually, he found the Minotaur, combat ensued, and using his father’s sword, Theseus slew the monster before returning to the surface victorious. Theseus and Ariadne then fled Crete, leaving the Queen bereft and the King without retribution.

Ariadne and Theseus by Jean-Baptiste Regnault

The Minotaur’s Legacy

The story of the Minotaur has permeated throughout history and has continued to influence many artists throughout the ages. Most notably, the Minotaur appears in Dante’s Inferno when Virgil guides Dante as they prepare to enter the seventh circle of hell. Giovanni Boccaccio and Dante Gabriel Rossetti also wrote concerning the Minotaur. Picasso, Dali, and Rivera have also featured the beastie in surrealist artworks.

So, was the Minotaur real, or is it just a myth? This is something we’ll never be able to 100% confirm or deny. However, it’s worth remembering that the Minotaur had another name, Asterion. He was named after his foster-grandfather and Crete’s first king, Asterion I. Prince Asterion was the son of King Minos and Queen Pasiphae and his name means ‘starry’.

Minotaur, by George Frederick Watts

It is entirely plausible that Asterion may have suffered from a medical condition that manifested in a facial deformity, giving him a bull-like appearance. Some coins that were minted at Knossos from the fifth century bore the resemblance of a kneeling bull, and had a star-rosette in the centre – a symbol for Asterion. Perhaps, this was ancient Crete’s way of acknowledging its mythic son.