Written by Ed Whalen, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The Romans were great builders and are still revered as great engineers. One of the greatest buildings they constructed was the Pantheon. A new theory argues that the building was designed to act as a sundial during the Spring Equinox, which falls between March 19 and 21. This view could offer insights into Roman religion and ceremonial life.

The Pantheon

The Pantheon was constructed during the reign of Emperor Augustus. Its Latin name means the temple of ‘all the gods’ and it played a very important part in the religious and public life of the city.

In the 2nd century AD, the structure was destroyed by a fire and was rebuilt by Emperor Hadrian (c 145 AD). The site, with its concrete dome (rotunda), is considered an architectural masterpiece and remains the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world. In the interior of the Pantheon is a massive circular floor and access is through a splendid portico flanked fifty-foot granite columns.

Today, the Pantheon is an extremely popular tourist site as well as a functioning Catholic Church.

A Giant Sundial?

In the dome, there is a circular aperture known as an oculus, through which light enters the interior. It was once widely thought that the twenty-seven foot wide oculus was designed to provide light and to help to cool the building in the brutal Roman summers. However, it has now been proposed that the oculus was constructed to make the Pantheon a giant sundial, tracking time by the location of the sun in the sky.

It has long been speculated that the Pantheon’s design was linked to the movements of the sun. Now two scholars believe they have shown a link between the building’s interior and the movements of the sun as seen through the oculus. They further argue that there are many similarities between the former temple and Roman-era sundials.

According to their study, the movement of the sunbeams appeared in the Pantheon’s interior via the oculus. This was important also for the calculation of the calendar. It is also believed that the temple played a role in the calculation of the equinoxes, which is when the night and day have equal hours and the sun sits directly above the Equator.

Researchers believe that beams of light hit above the door of the Pantheon at the Spring and Autumnal equinoxes, which were very significant dates to the Ancient Romans.

The Pantheon also played an important part in the ceremonial life of Rome. It is conjectured that the building was designed to allow light from the oculus to fall on the doorway on the 21st of April ever year, the anniversary of the founding of Rome. This was part of the celebration of the foundation of the city, one of the most important civic events in Rome.

The Pantheon was primarily a temple and it was once filled with statutes of the gods. It is believed that the light that fell from the oculus was a symbol of the solar deity, indicating his presence in the Pantheon.

Emperor, Religion, and Power

The Pantheon, as a sundial, may have played an important part in the ceremonial life of the Empire. Rituals and rites were used to proclaim and justify the absolute power of Emperors. The light falling through the oculus in the dome would have fallen on the Emperor during rituals, thus demonstrating his association with the sun gods.

In Rome, the Emperor was also the chief priest and it is possible that the light was used in some long-lost ceremony. The maintenance of the calendar was traditionally one of the main roles of the Emperor. In an era before mechanical clocks, the calendar and calculating time was often very challenging. Emperors such as Marcus Aurelius would have visited the Pantheon to track the movement of the sun as part of his management of the calendar, which symbolized his central role in the state. The Pantheon thus emphasized the sacred role of the Emperor and his role in ruling time.

Conclusion

The Pantheon is one of the most stunning buildings ever constructed. However, it is also still somewhat mysterious and enigmatic, even after almost 2,000 years. The theory that it was used as a sundial could help us to better understand this structure. If the temple was designed to act like a sundial it likely had a greater role in the ceremonial, public and civic life of the city than previously thought.

References:

Marder, T.A. and Jones, M.W. eds., 2015. The Pantheon: from antiquity to the present. Cambridge University Press.

Written by Ed Whalen, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The ancient Agora of Athens is one of the most influential archaeological sites and says a lot about the life of the Greeks. ‘Agora’ literally meaning ‘a place of gathering.’ It was a marketplace where every Athenian citizen participated in governance, overlooked judicial matters, traded commodities, exchanged ideas, or worked together to build the most dynamic society in the world.

In fact, the Agora of Athens is the birthplace of democracy. It is at this place that brilliant minds like Aristotle and Socrates gained popularity, taught their disciples, and eventually died.

For centuries, this area served as a common ground for merchants, artisans, politicians, and intellectuals. It was considered an honor to participate in such ‘common activities’ that led to the development of society. (A quick fact: the term ‘idiot’ or idiotis, was coined to mock people who avoided participating in such common activities.)

The history of ancient Agora of Athens stretches from prehistoric times to the modern age. For centuries, the marketplace was a hub of ideas and trades. The present archaeological site saw some devastating years when Persian invaders destroyed the structures completely in 490 BC, but rose again in the 5th century BC with the flourishing of Athenian culture.

Agora of Athens – the Archaeological Site

The Agora was built on flat area with a main street that hosted a market and philosophical activities. In the Agora of Athens, the two main structures were the Temple of Hephaestus and the Stoa of Attalos.

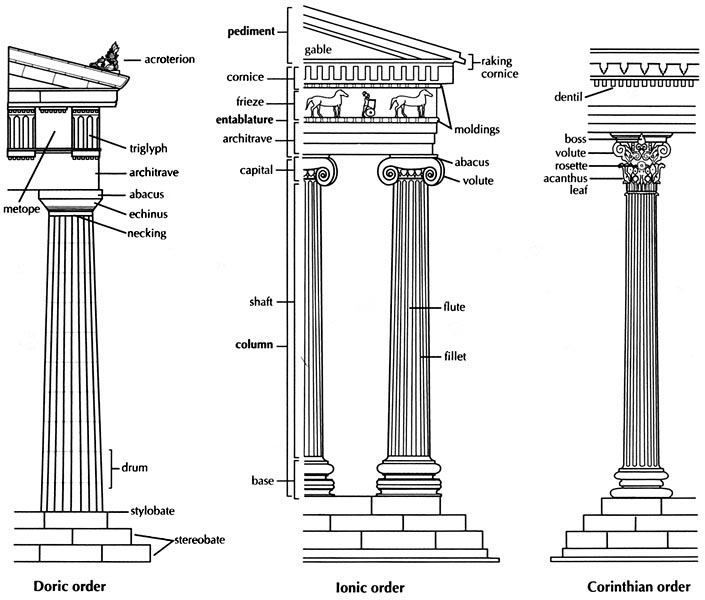

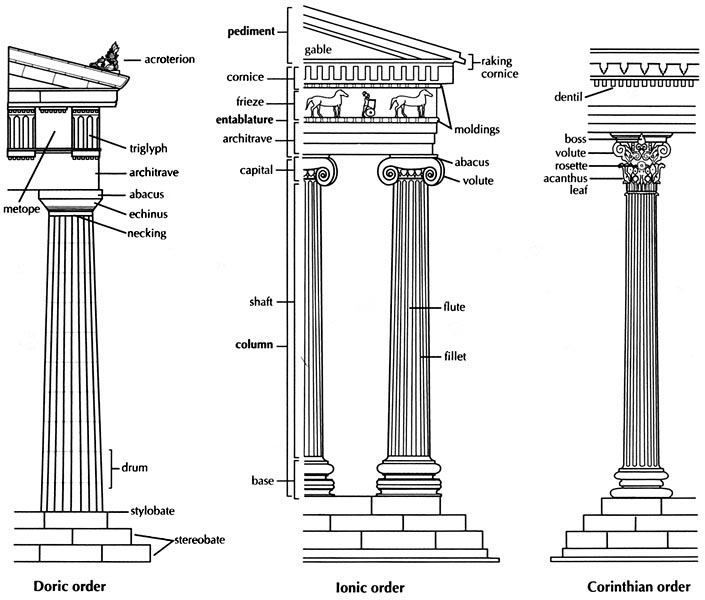

The construction of the Temple of Hephaestus began in 450 BC and still stands intact today. It is one of the most well-preserved Greek temples of the classical period. Being constructed in Doric order, the temple houses two bronze statues of the goddess Athena and Hephaestus. This north-western area of Athens was once a center of ironworking foundries; hence, the temple honored the god of fire and metal-smithing.

The Stoa of Attalos sits on the east end of the site and was built around 150 BC. It is an outstanding exemplar of ancient Stoa architecture and today it houses the Agora museum. Stoas were huge porticos where merchants stalled their goods. They also provided shelter for people during scorching summer days.

Another magnificent structure that punctuates the archaeological site is the Byzantine era Christian Church of the Apostles. Many other temples formerly stood in the Agora dedicated to Zeus, Apollo, and Ares.

These remained a mystery until 1934, when thousands of artifacts, Amphora pots, marble statues, and reliefs were found during excavations by the American School in Athens, providing a glimpse of life in ancient Greece.

Activities in Ancient Agoras

Apart from being a political hub, the Agora also acted as a communal place for religious activities. Every Greek city had an Agora, which consisted of a massive compound with a main road in the center surrounded by structures for social activities.

The Agora was easily accessible to every citizen, and people would meet there daily. It was the heart of the city that brought the society together. In addition, the Agora road led to the main gate of the city, serving as a sacred travel route for the Panathenaic festival, held in the honor of Athena every four years.

Athenian citizens took pride in being democratic. Their Agora acted as a space where great ideas, politics, judgments, and legal processions took place. Some of the world’s most important ideas, such as democracy and trigonometry, were probably discussed on its streets. City law courts and senate were located in the Agora, where political proceedings were held openly. Every Athenian had the right to vote for anything he believed in. Laws were posted in the Agora for the public to see.

Aristotle and Socrates frequented the Agora of Athens to discuss life and philosophy. Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine, and the mathematician Pythagoras were some other famous figures who instructed and shared their ideas in the Athenian Agora.

The activities that took place in the Agora went beyond mundane transactions. The ideas and philosophies born there have literally shaped the modern world. It is almost unimaginable to live in a world without democracy or mathematical formulas to calculate the sides of the triangle. The Agora was a provenance for life-altering principles for which Western civilization is forever indebted.

Written by Divya Gupta, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The most sacred structures in Greek Mythology were the enigmatic sanctuaries. Temples were usually located at the center of the sanctuary which was enclosed by walls from all sides. This spiritual place featured a massive landscape with sacred trees and springs. In the center of the area stood a monumental cult statue of the deity that the temple honored. The outdoor altar had several niches where statues of other gods and goddesses were erected.

Unlike modern churches and synagogues, the temple was not a place for rituals, but it was more like a home to the gods and goddesses. Most common people were not allowed inside the temple sparing a few occasions every year. The sacred precincts were built as a place to offer homage to the gods with gifts and offerings. Gigantic columns were the principal component in every temple. Greek architecture features three major types of columns – the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian, all of which can be seen in various temples even today.

Temples were located away from the city in a large area and would often benefit from the surroundings to express the character of the spiritual entity. So, a temple dedicated to the god of the sea would be constructed near the seashore.

While many of the Greek temples couldn’t stand the test of time, a lot of them can still be embraced today in Greece and the Southern parts of Italy. Here are some of the most iconic temples that glorify the rich history of Greek architecture.

The Parthenon, the largest Doric temple, was dedicated to the city’s patron goddess, Athena Parthenos. The construction of the temple began during the age of Pericles, around 447BC. This monumental structure stands as a testimony of power and glory, to honor the goddess of indomitable might. Hence the rocky location of the Acropolis served as the ideal location to portray the goddess’s strength. The ancient statue of the deity was made using ivory and gold, which was later stolen by the Persians.

The Parthenon

Today, the Parthenon is considered one of the most renowned UNESCO World Heritage sites, attracting millions of tourists every year. A trip to Greece is practically incomplete if you do not pay a visit to this magnificent structure.

The Temple of Hephaestus, dedicated to the god of metalwork, sits on the top of Agoraios Kolonos hill, merely 500 meters away from the famous Acropolis. The region was once considered as a hub of foundries and metal workshops and thus served as a perfect location for the temple. The Temple of Hephaestus was designed by the promising architect Ictinus, who also worked on the Parthenon. It is one of the most well-preserved Greek temples that stands intact even today!

The Temple of Hephaistos in Athens

Paestum was a famous Greco-Roman city in Southern Italy, very close to the shore. The sanctuary, constructed around 550BC is considered as a pioneer of Greek temples. The ruins of Paestum consist of three famous Greek temples all made in Doric orders. The temple of Hera, goddess of marriage and childbirth, is one of the oldest temples and has surprisingly still has its entablatures intact.

View of Paestum.

The temple of Apollo Epicurious, dedicated to the god of healing and Sun, is one of the most unusual Greek temples. The daring architecture consists of all three forms of segments, Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian, which gives the temple a unique character. Another bizarre attribute of this temple is that it opens up northward, unlike the rest of the Greek temples that are facing east. Located in the mountains of Peloponnese, this well-preserved temple stands as an evocative testament to the brilliance of Greek Architecture!

The Temple of Apollo Epikourios at Bassae, east colonnade, Arcadia, Greece

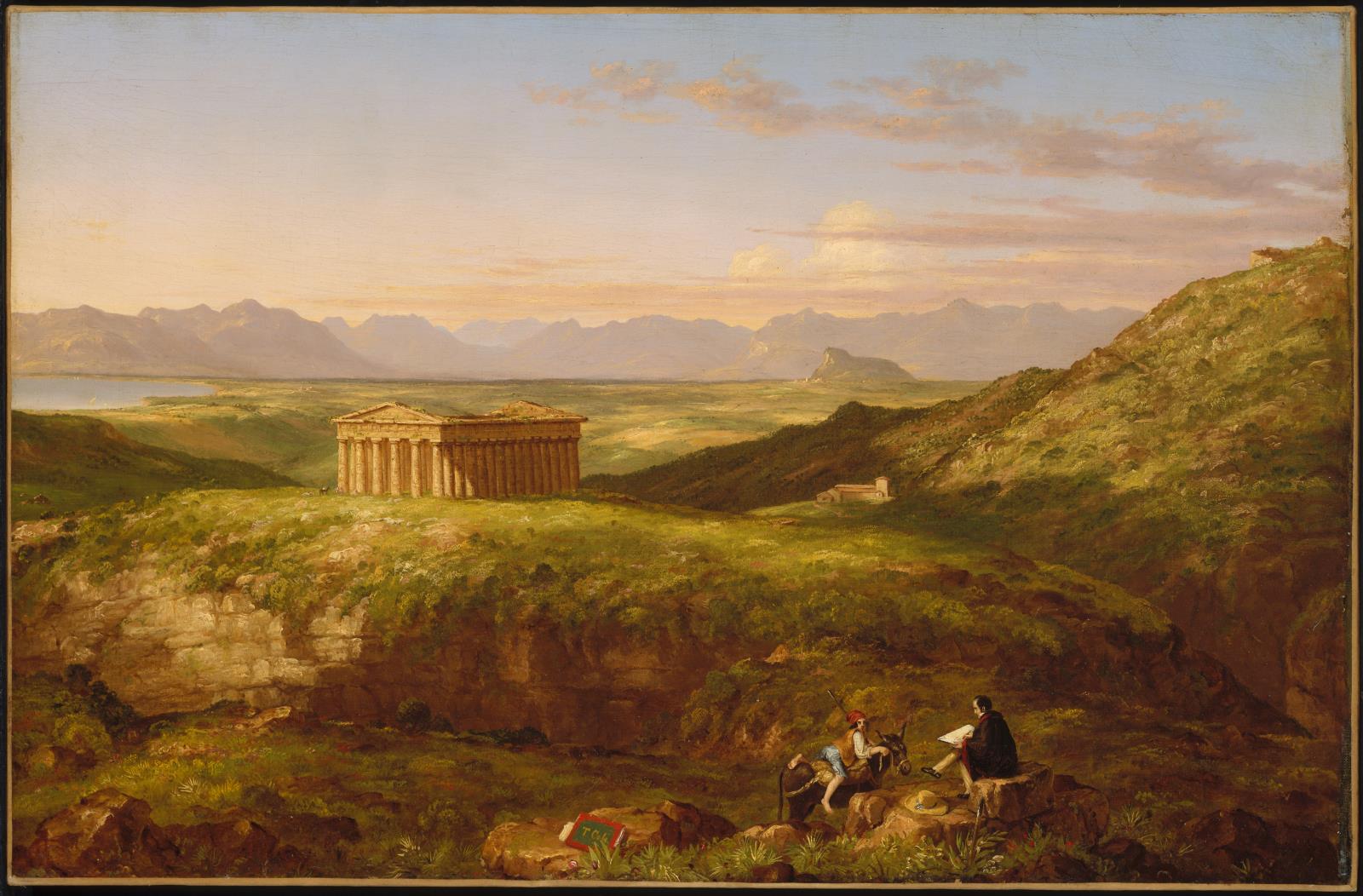

Located in the north-western part of Sicily, the temple of Segesta offers a distinctive experience to the viewers. Segesta was once inhabited by Elymians, the indigenous people of Sicily. With the widespread Greek influence, the region of Segesta adopted the new culture and blended easily. The temple follows all the strict features of Greek Doric Order but, on a closer look, one can see the unfinished structures. The temple of Segesta never actually had a roof or fluted segments. The inner chamber, also called naos, never really saw the light of day either.

The Doric temple of Segesta

Erectheum is probably the most popular Greek temple in the modern world. Every history lover and art enthusiast has read about the temple in a million articles, and words fall short to describe the beauty of its architecture! This antique sanctuary, located to the north of the Acropolis of Athens, features the most celebrated segment style, the Ionic Order. The iconic six female figures upheld in the yard, known as Caryatids, is one of the most magnificent examples of Greek architecture.

Temple of Erectheum

Sounion is considered one of the most important sanctuaries in the Attica region. The temple was erected in honor of Poseidon, the god of the sea. Hence, the sanctuary catapulted overlooking the gorgeous views of the sea from three sides. Once upon a time, this Greek Doric temple flaunted 34 grand columns made of white marble. But today, only 15 stand tall, preserving the marvelousness of Greek architecture.

Temple of Poseidon at Cape Sounion

Thousands of years later, these enchanting Greek temples still provide a window to the past and remain some of the best-preserved testaments to history.

References:

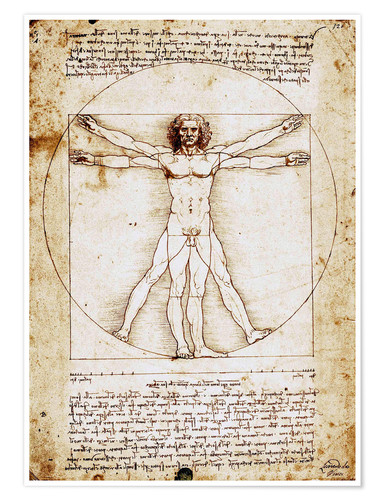

The story sounds like a Dan Brown thriller: Leonardo Da Vinci’s notebooks contain a skillfully executed, albeit curious image. A man with two sets of arms and legs poses in the center of a circle and square. With one set of arms forming a V and one set of legs out-splayed, the figure’s soles and fingertips define the circumference of the circle. With the other set of arms outstretched and legs straight, the figure defines the perimeter of the square.

Known in Italian as L’Uomo Vitruviano—the Vitruvian man—the c. 1490 image is perhaps the most recognizable of all Leonardo’s sketches. A simple internet search reveals literally hundreds of reproductions, adaptations, and parodies. It may come as a surprise that this sketch, unlike others, did not spring from Leonardo’s fertile imagination, but was designed to illustrate someone else’s ideas:

[I]f a man be placed flat on his back, with his hands and feet extended, and a pair of compasses centred at his navel, the fingers and toes of his two hands and feet will touch the circumference of a circle described therefrom. And just as the human body yields a circular outline, so too a square figure may be found from it.

This passage appears in Book III, chapter 1 of De Architectura, the only comprehensive work on architecture to survive from Classical Antiquity, authored by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio. It’s an interesting concept, to be sure, but what about it would inspire Leonardo to produce one of his most evocative drawings?

There is indeed much more to this story: behind the Vitruvian man stands an enigmatic builder, a learned manuscript, a legendary name, and cultural prestige.

Vitruvius qui de architectonica

So, who was the original Vitruvian man? Who was Marcus Vitruvius Pollio? The facts of his existence are few and the questions are many. To begin, even his name is a conjecture. His praenomen was most likely Marcus, but we’re not certain. The cognomen Pollio is also only probable. Faventinus, an architect writing in the 3rd century CE, is believed to be the first writer to use Vitruvius’ full name. However, an alternate theory suggests that he may have been referring to two separate individuals: a Vitruvius and a Pollio.

As with his name, almost everything else we think we know about Vitruvius is a matter of more-or-less certain extrapolation from brief autobiographical scraps in his De Architectura.

Of his background and upbringing, Vitruvius says only that his family was able to give him a good education. Similarly, when he makes observations about the preferred education for architects, he is clearly referring to his own. After all, in the first chapter of Book I, Vitruvius says an architect needs a wide-ranging education, which is precisely the sort of education he claims for himself in the preface to Book VI.

We would expect an architect to have working knowledge of mathematics, materials, and physics. But what about pre-Socratic philosophy? Indeed, Empedocles’ elemental philosophy is essential to the city planner. Like many Classical thinkers, Vitruvius derived from Empedocles the belief that differences between human groups reflected different elemental mixtures. The blend of elements in the Gauls, for instance, was vastly different from the corresponding blend in the Egyptians. Therefore a building site that would be healthy for one group would be harmful to another. Put in practical terms, Vitruvius held that a wise city planner should know how to select particular environments that promote the general health of the citizenry.

In other parts of De Architectura, Vitruvius expresses familiarity with Eratosthenes’s calculations of the circumference of the earth and Pythagoras’ philosophy of harmony. Needless to say, Vitruvius also owes much to Aristotle. On a basic level, Vitruvius’s statement about the three divisions of architecture —usefulness, durability, and beauty—merely specifies Aristotle’s assertion that the goal of all human endeavors is some definable “good.”

No mere theorist, Vitruvius states that much of his know-how was learned hands-on. “I myself know by experience,” he remarks. In parts of the work, he gives details on construction techniques, materials, and the machines used in building. He states that he superintended the construction of a basilica in Fano. Occasionally, he gives details that seem to come from the workshop, such as his claim that bricks should be dried for a full five years before use, whereas cut stone need only be seasoned for two.

In several passages, Vitruvius also mentions his military service. He says he built artillery pieces for Julius Caesar, and gives detailed instructions for such weapons as ballistas and scorpions. He even refers familiarly to how experts evaluate whether these weapons are well made: the control ropes vibrate at a certain pitch, like a well-tuned musical instrument.

A few historians have tried to identify our Vitruvius as a contemporary, Marcus Vitruvius Mamurra, possibly because Mamurra was also a military engineer and also served under Julius Caesar. Such an identification is highly unlikely since Mamurra is believed to have died around 43-46 BCE. Moreover, Mamurra was known for ostentation and graft. Our Vitruvius claims that he preferred honest poverty:

I have never been eager to make money by my art,” he writes, “but have gone on the principle that slender means and a good reputation are preferable to wealth and disrepute.

An Unlikely Authority

All this makes up the merest outline of a life. And if we look to Roman writers of the era for corroboration, the picture does not become much clearer. Scholars have identified only five Roman writers who mention Vitruvius or his book. These are Pliny the elder, Frontinus, Faventinus, Servius, and Sidonius. As we shall see, how they discuss the man and his work would change as time passed.

Pliny the elder knew De Architectura and listed Vitruvius as a source in his Natural History, but doesn’t mention him by name in the text.

Vitruvius’s name also appears a few decades later in a technical report written by the Roman official Sextus Frontinus. His De Aqueductibus Urbis Romae briefly mentions a Vitruvius who had a supervisory or advisory role in pipe repair or construction. However, Frontinus says nothing more, not even what aqueducts Vitruvius and his pipefitters worked on. De Architectura is not mentioned at all.

A few centuries later, however, the name “Vitruvius” appears to have become culturally significant, shorthand for architectural excellence. We can see this in an abridgement of De Architectura produced by the 3rd-4th century CE architect M. Cetius Faventinus. His De Diversis Fabricis Architectonicae highlights the practical aspects of Vitruvius’s book and leaves out most of the learned theory. By doing this, Faventinus created a handbook on methods and materials for a new audience.

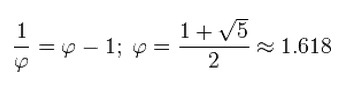

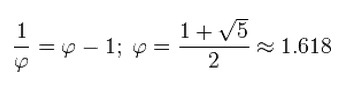

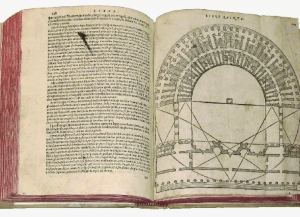

An Illustration from De Architectura. Vitruvius illustrated his theories and rules with technical drawings and examples. Source: idesign.wiki

Vitruvius wrote for the political and philosophical elite. Faventinus seems to have written for supervisors, builders, and contractors. Although this change in audience is significant, even more significant is the fact that Faventinus attributed the work to Vitruvius.

In the world today it is generally held that newer is truer. All else aside, a technical report published in 2019 is considered more reliable than a similar report from 2009. In Classical Rome, the opposite belief held true. Older information was considered more trustworthy because it had stood the test of time.

In attributing the summary to Vitruvius, Faventinus was emphasizing the work’s trustworthiness: it was a handbook from the golden age of Rome. It was not just information; it was Vitruvius’s timeless advice. Copies of Faventinus spread throughout the western empire and were copied by generations of monks for the next thousand years.

Of course it could be argued that Frontinus and Faventinus were builders writing for other builders. Even Pliny was focused on scientific issues. It would not be unusual for such writers to mention Vitruvius or cite his work.

But what, then, are we to make of a literary critic who also cites Vitruvius while discussing poetic diction? In the late 4th century to early 5th century CE, our fourth writer, M. Servius Honoratus, references Vitruvius in his commentaries on Virgil’s Aeneid. In Book VI, Aeneas and his companions arrive at the Cumean Sibyl’s grotto:

Deep in the face of that Euboean crag

A cavern vast is hollowed out amain,

With hundred openings, a hundred mouths,

Whence voices flow, the Sibyl’s answering songs. (Line 43)

Discussing Virgil’s poetic diction, Servius cites “Vitruvius the architect” to explain Virgil’s meaning in using such words for access points as aditus and ostia. The commentary would be reasonable only if Servius and his contemporaries believed Vitriuvius was the authoritative answer for any architectural question, whether actual or literary.

An even more lofty status is attributed to Vitruvius at the end of the fifth century CE.

In an ironic letter to a contemporary, the late Roman official and bishop Sidonius Apollinaris rhetorically equates Vitruvius’s mastery of building to Orpheus’s mastery of music, Aesculapius’s mastery of healing, or Euclid’s mastery of geometry (Book IV, chapter 3, 5). In a different letter, he tells his reader that Vitruvius’s book, likely Faventius’s digest, is indispensable for domestic repairs and construction.

Nature as Architect

As historians have suggested, Vitruvius’ status as the leading authority on architecture persisted well into the Italian Renaissance. Whatever else was lost in the collapse of the Roman empire in the west, the concept of Rome as the apex of cultural prestige certainly survived. Likewise, we know that Faventinus’s digest of Vitruvius survived.

Those who aspired to create monumental works like those of the Roman empire, had much to learn from Vitruvius. Certainly the breadth of learning he demonstrated, along with his hard-won practical know-how appealed to Renaissance thinkers like Leonardo. They considered him one of their own.

Vitruvius’s book is not just about architecture, after all, but about architects and builders as well. What he writes about architects surely appealed to Renaissance architects and engineers—even part-timers like Leonardo. To Vitruvius the architect had a hallowed heritage, stretching back to the framing of the universe:

The heaven revolves steadily round earth and sea on the pivots at the ends of its axis. The architect at these points was the power of Nature, and she put the pivots there, to be, as it were, centres, one of them above the earth and sea at the very top of the firmament and even beyond the stars composing the Great Bear, the other on the opposite side under the earth in the regions of the south. Round these pivots (termed in Greek πόλοι) as centres, like those of a turning lathe, she formed the circles in which the heaven passes on its everlasting way. In the midst thereof, the earth and sea naturally occupy the central point.

Nature itself, according to Vitruvius, is an architect. The architect is, in a certain sense, carrying on and trying to imitate the works of Nature. It is not difficult to imagine why the work in which this passage appears would inspire Leonardo so many centuries later.