How Authentic is Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief?

PURCHASE YOUR HARDBACK EDITION HERE

Written by Justin D. Lyons, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

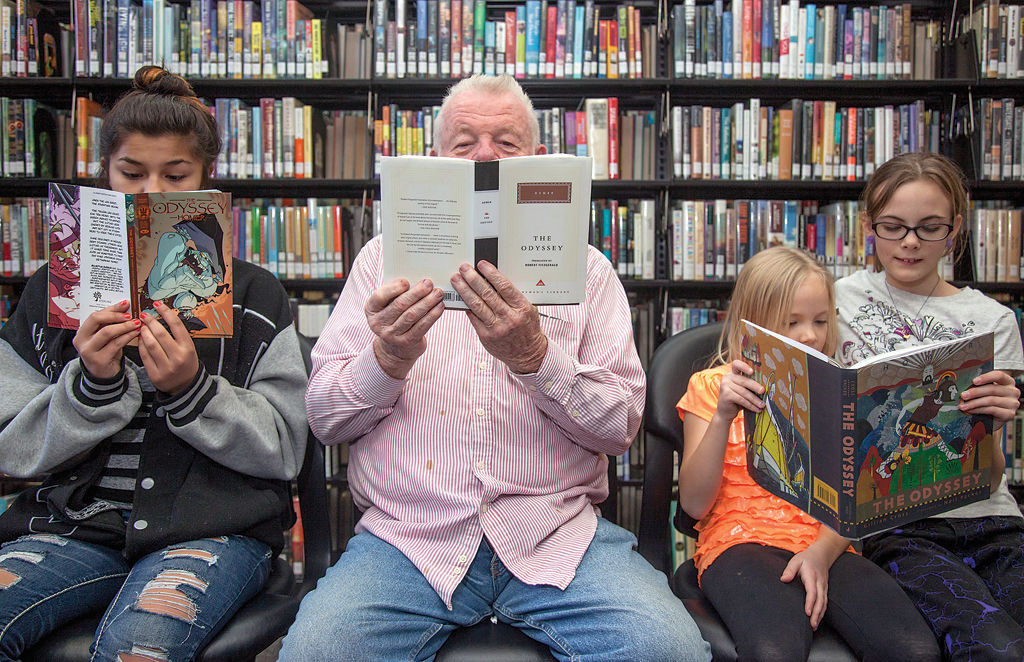

The most well-known episodes in Homer’s Odyssey are the adventures described in Books 9-12. Full of one-eyed giants, amorous goddesses and narrow escapes, they are considered the most memorable and thus most likely to be included in collections of excerpts. They have received so much attention that it is often forgotten that they make up only a small part of the epic—an epic that is far more concerned with the homecoming of Odysseus than with his wanderings.

These stories are told in the first person by Odysseus himself. Given what we know of his character from both the Iliad and the Odyssey, Odysseus does not hesitate to deceive when circumstances allow. Thus, we should carefully consider the veracity of his tales. After all, Homer calls Odysseus a “man of twists and turns,” and we expect him to live up to the description.

Odysseus’ reputation thus begs the question: Is it possible that the tales are not meant to be taken as relating “real” events? In other words, could it be that Odysseus did not actually have these adventures, or at least did not have them as he relates them?

The stories Odysseus tells have a fairy-tale, magical quality about them that is different from the rest of the Odyssey. The unreal, dream-like world of monsters and enchantresses is distinct from the more realistic, historical world of Ithaca and the Greek mainland. Further, Odysseus’ stories interrupt the forward-moving time scheme of the poem; they have the character of flashbacks, contributing to the feeling of “unreality.”

It should be noted that Odysseus is speaking to an audience, the Phaeacians, from whom he is in desperate need of aid. Certainly, Odysseus is not above using his stories to sway them according to his desire.

Indeed, Odysseus may have been catering to King Alcinous, who expressly asks to hear of his guest’s exciting travels:

But come, my friend, tell us your own story now, and tell it truly. Where have your rovings forced you? What lands of men have you seen, what sturdy towns, what men themselves? Who were wild, savage, lawless? Who were friendly to strangers, god-fearing men? Tell me, why do you weep and grieve so sorely when you hear the fate of the Argives, hear the fall of Troy? That is the god’s work, spinning threads of death through the lives of mortal men, and all to make a song for those to come… (Odyssey, VIII.640-650)

Odysseus’ tales conveniently sound these same themes: the savage, the hospitable, the pious, the lawless, and death. Odysseus is on next after the great bard, Demodocus, has regaled the assembly with his songs, one of which was suggested by Odysseus himself and glorified his exploits at Troy.

Odysseus has a big act to follow and, as he is about to announce his identity as the Odysseus about whom the Phaeacians have just heard so much, it would obviously not do to disappoint. Homer here refer to Odysseus as “the great teller of tales.”

Both the reader and the Phaeacians are expecting something big, and Odysseus delivers. The Phaeacians respond well to the stories, hanging on Odysseus’ every word and showering him with even more gifts. Would not someone of Odysseus’ resourcefulness be expected to knowhow they would respond and be able to tailor his adventures to the tastes of his audience?

The Phaeacians appear to be a relatively innocent people. They are no match for devious Odysseus. King Alcinous goes so far as to praise Odysseus for his honesty:

‘Ah Odysseus,’ Alcinous replied, ‘one look at you and we know that you are no one who would cheat us—no fraud, such as the dark soil breeds and spreads across the face of the earth these days. Crowds of vagabonds frame their lies so tightly that none can test them. But you, what grace you give your words, and what good sense within!’ (Odyssey,XI. 410-415)

The King’s words must come off as ironic to any reader or listener aware that wiliness is the epitome of the Odyssean character. Homer, being well-acquainted with the Odyssean character, already knows what we will think about Alcinous’ remark.

Later in the poem, when Odysseus reached Ithaca, it is amply demonstrated that he is a consummate liar. Upon arriving, he spins a series of bold-faced deceptions, commonly referred to as the “Cretan lies.”

At first, he tries to deceive a shepherd boy, who turns out to be Athena in disguise.

She, of course, sees through him:

“Any man—any god who met you–would have to be some champion lying cheat to get past you for all-round craft and guile! You terrible man, foxy, ingenious, never tired of twists and tricks—so not even here, on native soil, would you give up those wily tales that warm the cockles of your heart!”

What better candidate could there be for these “wily tales” than the stories Odysseus so recently told to the Phaeacians?

Homer has left us many textual clues which suggest that the stories Odysseus tells the Phaeacians are not meant to be taken as having “really” happened. Such a view of these stories should encourage us always to be careful readers. We may encounter unexpected “twists and turns” that reveal more and deeper levels of art and meaning, inspiring us to read old books with fresh eyes.

Written by Frank Hamilton, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Every student of political history recognizes the role of ancient Greek and Roman societies in shaping modern political thought.

Democracy was first developed in ancient Greece, while the Roman empire developed the political concept of a republic. Both political ideas are still important today.

As ancient Greece influenced Rome, ancient Greek and Roman political philosophy has influenced the political framework of several western societies even after a millennium.

Therefore, a look into the workings of ancient political structures is incomplete without proper attention given to the political setup of ancient Greek and Roman societies.

Aristotle’s Politics and Cicero’s De Republica can guide us in better understanding the political setup of both ancient empires.

While these two works are helpful, there are several other books that explain how ancient Greek and Roman societies functioned.

Thus, without further ado: here are the 10 best books about ancient politics.

1. Politics and Society In Ancient Greece, by Nicholas F. Jones

Nicholas F. Jones is a professor of Classics at the University of Pittsburgh. He has authored four books on ancient Greek political and social history.

In this book, Jones provides a concise summation of the best historical knowledge of ancient Greece. Since several modern democracies were inspired by ancient Greece, Politics and Society In Ancient Greece helps readers understand the complexity of Greek political life and how that may reflect in the modern political landscape.

2. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, by Edward Gibbon

This book comprises six volumes covering the history of the Roman Empire from 98 CE TO 1590, including the Islamic and Mongolian conquests.

In it, Gibbon traces the history of Western civilization, from the peak of the Roman Empire to its fall. He offers a critical, fairly objective analysis of history, with the occasional moralization.

“History,” he writes in The History of the Decline And Fall of the Roman Empire, “is indeed, little more than the register of the crimes, follies, and misfortune of mankind.”

3. The Ancient City: A Study of the Religion, Laws, and Institutions of Greece and Rome, by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges

Published in the 19th century, this book remains French historian Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges’ most popular, and is based on texts of ancient poets and historians. In it, Fustel de Coulanges investigates the genesis of the institutions of Greek and Roman society.

He provides a fresh, accurate, and detailed picture of the religious, family, and civic life in the ancient world, covering, for example, Athens during the time of Pericles and Rome during the time of Cicero.

4. Democracy: A Life, by Paul Cartledge

Released in 2018, this is the most recently-published book on this list and in it, Paul Cartledge offers a detailed history of the ancient Greek political system.

The book also covers the disparities between ancient Greece and modern types of democracy, helping us form a better understanding of both.

Democracy: A Life traces the evolution of Greek politics — including how the political theory was invented — and the birth of democracy.

The book also traces the decline of Greek democratic institutions at the hand of the Macedonians, and ultimately the Romans.

5. Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic, by Tom Holland

Published in 2003 by Cambridge-educated author Tom Holland, Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic covers the end of the Roman republic and birth of the empire.

Rubicon refers to the river that Julius Caesar crossed with his army in 49BC before plunging the nation into civil war.

6. The Birth of Politics: Eight Greek and Roman Political Ideas and Why They Matter, by Melissa Lane

In this book, Melissa Lane traces the origin of political concepts, from Socrates to Cicero. The author shows how the following political ideas from the Greco-Roman world remain influential today. These ideas are:

The Birth of Politics provides a thoughtful and challenging discussion of traditional classical political ideas.

7. The Republic, by Plato

Plato’s work is the oldest published book on this list. Authored around 375 BC, it is written in Socratic dialogue. Considered one of the most influential philosophical and political works in history, Plato’s Republic attempts to define justice and the ideal community. The work also analyzes the merits and demerits of various forms of government.

8. Social Conflicts in the Roman Republic (Ancient Culture & Society), by P.A. Brunt

This is an easy-to-read book about the Roman republic. It offers a good picture of Roman history from the early republic to the time of Augustus Caesar, but lacks good sourcing. It’s good for those seeking a quick overview of the Roman republic, but is not necessarily a work of scholarship.

9. Greece and Rome at War, by Peter Connolly

This a vividly descriptive book that offers an overview of twelve centuries of conflict spanning more than half a century, from 800 BC to 450 AD.

10. The Roman Revolution, by Ronald Syme

Published in 1939, this is a scholarly work about the final years of the Roman republic and Augustus Caesar’s creation of the Roman empire.

In Conclusion

The books on this list will provide readers with a deeper understanding of the workings of ancient political systems and how they have influenced modern political philosophy.

Frank Hamilton has been working as an editor at essay review service Writing Judge and an author at Best Writers Online. He is a professional writing expert in such topics as blogging, digital marketing and self-education. He also loves traveling and speaks Spanish, French, German and English.

Written by Nicole Garrison, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The Hellenes and Romans sure knew how to create and appreciate exceptional literature. So for all of you who are contemplating whether you should add some classics to your reading list, trust me, you should!

In the times of the ancient Greeks and the Roman Empire, literature was a prime source of entertainment. It was also used to explore new ways of thinking and philosophical expression. Just as we spend our idle days browsing the internet and checking our social media for new posts, they spent their days discussing philosophy, attending the theatre, and crafting works of art.

Thanks to the way they used of leisure time, we are now lucky enough to have all those masterpieces that give us a glimpse into the life, thoughts, feelings, and philosophical reflections of the ancient world.

Anyone looking to expand their horizons, learn something new, or find a better way to pass their time than scrolling through a newsfeed, should give ancient Greek and Roman literature a try. From romance to mythology, here is the must-read list from the ancient world:

1. Medea (Euripides)

Euripides is one of the three Greek tragedians whose plays managed to survive. The most famous play by Euripides is Medea.

Based on the myth of Jason (leader of the Argonauts), this plays tells us the tragic story of Jason and his wife, Medea.

It is the story of betrayal, vengeance, and cruelty. Medea’s grotesque act of jealousy and search for revenge will leave you breathless. She definitely took rage to the next level when she killed her own children after Jason left her for another woman.

To find out how it all played out for her, you have to read Medea.

2. Antigone (Sophocles)

Your family issues will seem like nothing after you are finished reading Antigone. This Greek tragedy centers around family ties, a woman’s assertiveness, and civil disobedience.

The story revolves around the deaths of Antigone’s brothers – Eteocles and Polynices. After Antigone’s uncle, the king Creon, forbade the burial of Polynices because he attacked his brother for the throne, Antigone decided to defy the king’s order.

In addition to being a captivating read, Antigone will make you question the deeds of our heroes and anti-heroes. There’s some sort of justification for each “bad deed” as well as some criticism for the seemingly “good deeds.” It up to you to interpret and reflect on characters’ decisions.

The simple truth behind the controversy of Antigone’s story is the hardship of choosing the right between two wrongs. Is it right to show disrespect to authority to bury her mutinous brother? Or was it right to respect the king’s decision and allow that one of her family members doesn’t get a proper burial? What would you do?

3. The Odyssey (Homer)

You have probably heard of (or possibly even read) Homer’s Iliad, the famous telling of the Trojan War. But what about the Odyssey?

A translator of the ancient works and a writer at TopEssayWriting, Angela Baker, shared why the Odyssey is a book worthy of every student’s attention.

“[The] Odyssey is also an exceptional and exciting Homer’s work. It takes us on Odysseus’s journey and his adventures on his travels back to Ithaka. Aside from reading about how a victorious Greek leader, Odyssey, and his loyal entourage took down a Cyclops, this book will also get you thinking and questioning some of Odyssey’s decisions.”

Odysseus is not our typical “good guy” type of hero. Some of his actions, such as brutally killing Penelope’s suitors or cheating on loyal and patient Penelope, are somewhat questionable. But that’s exactly what makes this book so amazing. It will leave a lasting impression on you long after you have finished reading it.

Don’t think that every Greek classic is filled with tragedy, murders, and sadness. Aristophanes is a comic playwright whose bizarre comedy, Lysistrata, is full of wit and wisdom (read it here).

The hero of this story is Athenian woman Lysistrata, who thought of a revolutionary way to motivate men to win their battles: she led women in a protest that was based on the decision to deny sex to all men of the land until they establish peace with Sparta.

This comic story influenced several films such as The Second Greatest Sex (1955), The Girls (1968), The Baggy Trousers Case (1983), and Chi-Raq (2015).

5. The Satyricon, by Petronius

Delve into class struggle in Roman society in the 1st century AD Rome with Patronius’ Satyricon. You’ll learn about Roman history while being entertained by Petronius’ stories.

One of the most famous parts of Satyricon is the “Trimalchio’s Dinner,” which details the lavish yet unrefined tastes of the nouveau riche members of society.

Diana Adjadj, a writer at GrabMyEssay, said, “Don’t get surprised if you find some resemblance between the people’s behavior then to how people act now. This comic, picturesque, and highly-realistic novel will show you that centuries can pass, and lifestyles can change, but people’s nature, in essence, stays the same.”

6. Metamorphoses (Ovid)

Metamorphoses is the magnum opus of the incredible Roman poet Ovid. Despite his tragic destiny, Ovid wrote devotedly about love in his works.

What Metamorphoses will provide you with is hundreds of stories woven together by the repeating theme of transformation or metamorphosis. Learn more about the gender politics of ancient Rome, jog your memory about different myths you heard as a child, and enjoy stories of both joy and tragedy.

Metamorphoses inspired the artwork of numerous painters, so you can see elements of these stories on the walls of museums the world over.

Well, there you have it. These six Greek and Roman classics have the power to question your beliefs, weigh good and evil, and, most of all, educate and entertain you. Let these masterpieces take you on unbelievable adventures and introduce you to some of the most famous myths and heroes known to Western civilization.