Was Cyrus the Great TRULY Great?

By Edward Whelan, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

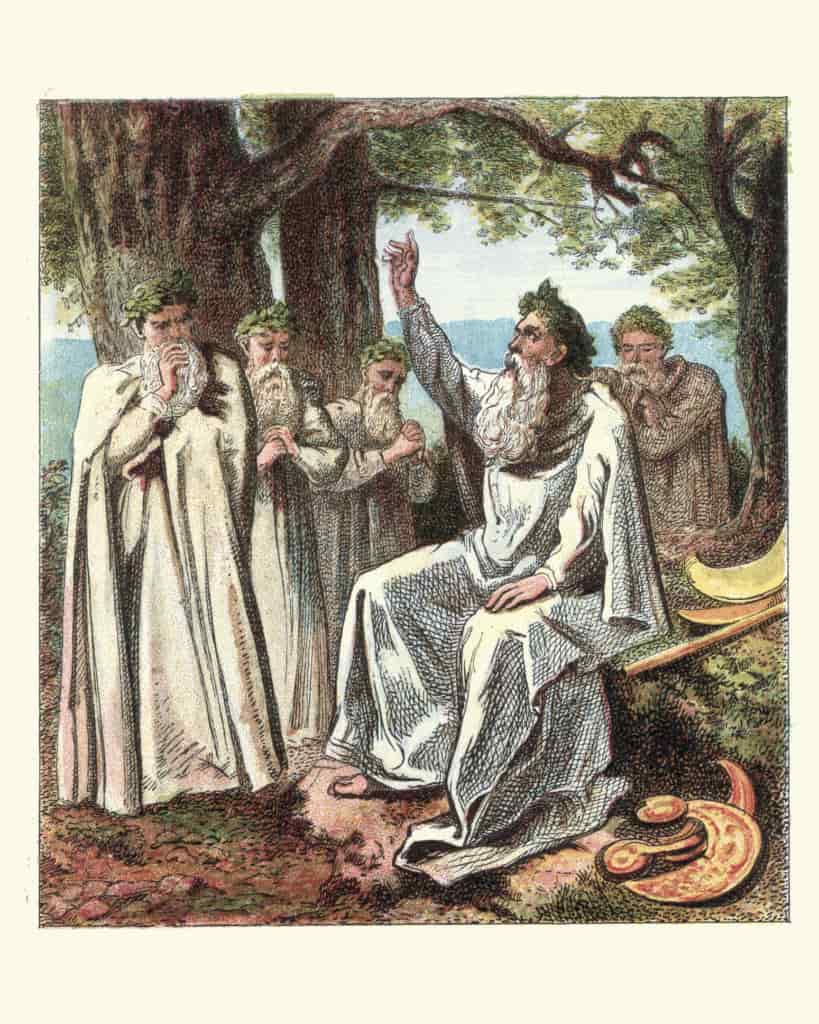

The Druids were one of the most important groups in Celtic society, which dominated much of Europe before the rise of the Roman Empire. The druids were the Celts learned class and they were magicians, healers, philosophers, poets and lawyers. They were central to Celtic life and were central to the Celts resistance to Roman expansion.

The Celts and the Druids

The druids were mainly priestly and were a distinct caste in Celtic society. They were members of the elite and they were the priests of the Celtic people. They had esoteric knowledge and practiced rituals that allowed people to communicate with the Gods.

Druidism can be likened to a shamanistic or natural religion. The Celtic priests taught that the natural world was a channel to the world of the spirits and the realms of the Gods. The Celts practiced a polytheistic religion that worshipped many gods and goddesses. They held that many natural phenomena such as trees and springs held magical powers. Druids, it was believed, could harness these powers by special rites.

Ancient Greek writers have left accounts of Druids performing ceremonies such as cutting mistletoe off sacred oak trees on nights with full moons. They would then make potions, something the Celtic learned class had a profound knowledge of (along with herbs), that would help women and men to be more fertile.

Their perceived ability to perform magic meant that the Druids had immense social and political prestige. In early Irish chronicles the Druids are recorded as having the ability to change the tide of battle, such as by healing warriors and allowing them to return to the fight. The Druids were also bards and their poetry was held to have magical qualities and it was believed that one of their satires could literally result in the death of the person being ridiculed.

Druidic Philosophy

The Classical writers regarded the Celts as little more than barbarians. However, even they stated that the Druids were very sophisticated and esteemed them as philosophers. The Celtic learned class believed in the transmigration of souls, that is they subscribed to the doctrine that the soul was reincarnated after death. It was believed that Druids could help the deceased to live again in a paradise-like otherworld or be reincarnated in another body. How this was done is not known.

Druid philosophy was based on the idea of eternal cycles and for this reason they revered the solstice and equinox. The Celtic priests believed that the number three was sacred and that the cosmos was divided into three parts. The also believed in Trinities of Gods. The symbol of three interconnected spirals was a very important religious symbol for the Celts and it was often inscribed onto their monuments.

Druids and Human Sacrifices

The Druids were condemned in Classical accounts of the Celts, because they practiced human sacrifices. Julius Caesar, in his work on the Gallic Wars, describes Druids sacrificing humans to the gods. In one memorable account, he describes Druids in white robes, having people placed in giant straw figures. These ‘wicker men’ were set on fire and those inside all burned to death. This was done to win the favour of the gods. There are some who claim that accounts of Druids conducting human sacrifices are merely Roman propaganda.

The organization of the Druids

The Druids were a special caste and they had certain privileges in Celtic society. The Celts adopted Greek writing and became literate. However, the Druids did not write down their beliefs or practices. All their knowledge and philosophy were passed down orally and this was done to protect their status as a special group.

It is believed that some of their lore data back to the Stone Age. Much of their learning on magic, healing, etc., was handed down by verses that were memorized. Some Druids were specialists and focused on wizardry or were traveling poets. According to Caesar there were High Druids who commanded the order of Druids. They were elected or else they won their position through battle. Interestingly many leading Druids were females’, and this is indicative of the high status of women in Celtic society.

The End of the Druids

The Romans greatly feared the Celts or Gaul’s, as they called them. This was because they had sacked Rome in the 5th century BC. During Julius Caesar’s campaign in Gaul he destroyed many Druidic shrines and sought to curtal their influence. He, like other Romans, knew that they were among the most determined to resist their rule.

After the conquest of Gaul, the Druids were all but outlawed and many of their rites were prohibited. During the Roman invasion of Britain, the Druids were at the forefront of the opposition to the legions. It is known that they were often counsellors to local Celtic kings and rulers. The Druids staged a desperate last stand on the Welsh Island of Anglesey in the final phases of the Roman conquest of Britain.

After the legion’s conquest of Britain, the Druids were outlawed as in Gaul. They went underground, and they continued to practice many aspects of Druidism. In Ireland, the Druids continued to practice their ancient religion and remained the learned class.

However, it was the arrival of a new religion, Christianity which really led to the demise of Druidism, even in Ireland. In various saint biographies, Christian saints are shown as defeating the Druid’s magic with the power of prayer. However, the Druids remained and continued the traditions of the ancient Celts even in the Early Middle Ages, as can be seen in the figure of Merlin in the tales about King Arthur.

References

Chadwick, Nora (1989). The Druids. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. Cardiff.

The AK-47 of the Ancient Near East

By Cam Rea

The Scythian bow was the AK-47 of the Ancient Near East and the weapon of choice to dominate the battlefield. Even though the bow was uniquely designed to deliver the utmost damage, the arrow itself was even nastier! Scythians created their arrowheads for maximum penetration of the opponent’s armor. Beyond that, Scythian arrowheads were extremely poisonous.

But before we pick our poison, we must pick our point.

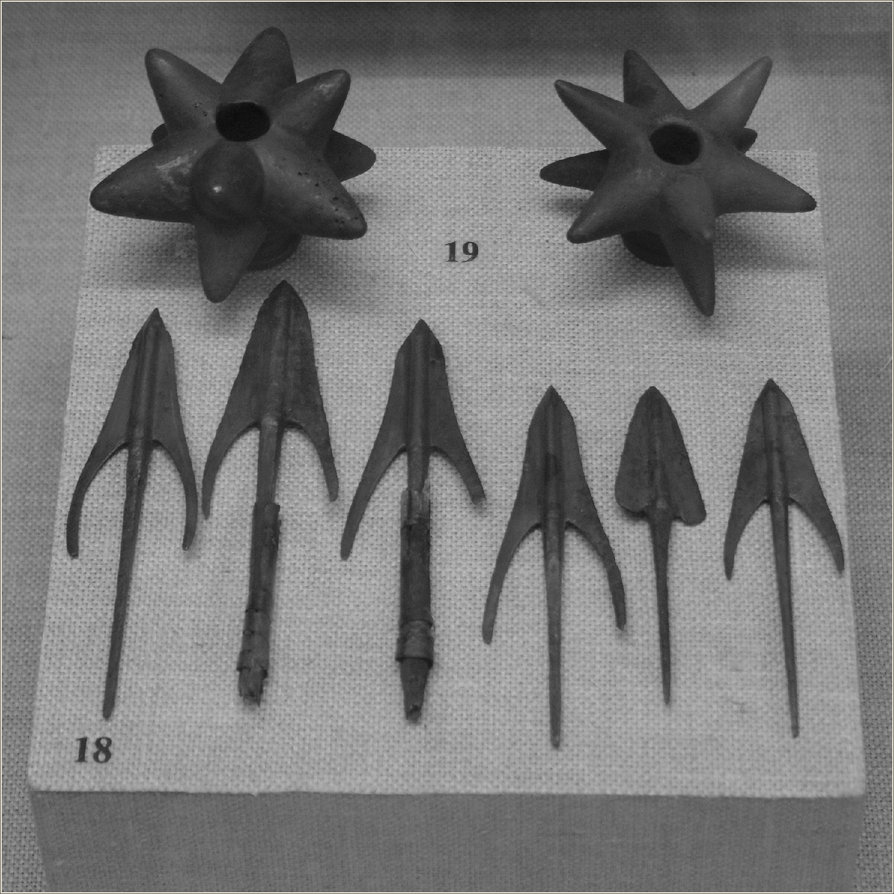

The Scythian arrowhead

The Scythian arrowhead, also known as a “Scythian point,” was a trilobate shape, designed like a rocket or bullet with three blades extending from the body. Some of the arrowheads had protruding barbs, while others lacked this painful extra. The trilobate was usually made of bronze, while the shaft used to deliver the arrowhead was made of reed or wood and was roughly 30 inches long. The design and craftsmanship employed was brilliant, for its aerodynamic body made it extremely practical to use against the finest and toughest of armor.

The Scythian point originated around the 7th century BCE, suggesting that Scythians developed the weapon in order to pierce Assyrian armor, as Scythians and Cimmerians were indeed at war with Assyria on and off during that time period. Now, this was not the only arrowhead style or material used by the Scythians, for some arrowheads were made of bone, stone, iron, or bronze. As for shape, some looked like small spearheads, while others were leaf-shaped, which may have been used for hunting. The discussed trilobite shape, however, was most likely used for combat purposes.

Besides the lethal design of the Scythian trilobite point, another nasty feature was the poison. Not only were these ancient fighters experts at archery, but also in biological warfare. Fortunately, or unfortunately depending on how you see it, the Scythians had a wide variety of deadly poisons to choose from. The not so friendly reptiles inhabiting the area included the steppe viper, Caucasus viper, European adder, and the long-nose/sand viper.

Map of Scythia and the Persian Empire

Truly, the Scythians had a vast arsenal of snake venoms of all degrees at their disposal. The book titled, “On Marvelous Things Heard,” by Pseudo-Aristotle, which was a work written by his followers, if not written in part by Aristotle himself, mentions the Scythian handling of snakes and how to extract their poison:

“They say that the Scythian poison, in which that people dips its arrows, is procured from the viper. The Scythians, it would appear, watch those that are just bringing forth young, and take them, and allow them to putrefy for some days.”

After several days passed, the Scythian shaman would then take the venom and mix it with other ingredients. One of these concoctions required human blood:

“But when the whole mass appears to them to have become sufficiently rotten, they pour human blood into a little pot, and, after covering it with a lid, bury it in a dung-hill. And when this likewise has putrefied, they mix that which settles on the top, which is of a watery nature, with the corrupted blood of the viper, and thus make it a deadly poison.”

The Roman author Aelian also mentions this process, saying, “The Scythians are even said to mix serum from the human body with the poison that they smear upon their arrows.” Both accounts show that the Scythians were able to excite the blood in order to separate it from the yellow watery plasma. Once the mixture of blood and dung had putrefied, the shaman would take the serum and excrement and mix it in with the next ingredient, venom, along with the decomposed viper. Once the process was complete, the Scythians would place their arrowheads into this deadly mixture ready for use.

The historian Strabo mentions a second use of this deadly poison:

“The Soanes use poison of an extraordinary kind for the points of their weapons; even the odour of this poison is a cause of suffering to those who are wounded by arrows thus prepared.”

So the arrowhead was poisonous, but why stop there? Sometimes they ensured that the barbs on the arrowhead were also coated with the deadly concoction. The Roman poet Ovid, who was exiled to the Black Sea, got a good look at these poisonous plus arrows and reported them as “native arrow-points have their steel barbs smeared with poison, carry a double hazard of death.” He also described the poisonous ingredient as “yellow with vipers gall.”

To get a better understanding of this “double death,” Renate Rolle elaborates further on the barbed arrowheads: “These arrowheads, fitted with hooks and soaked in poison, were particularly feared, since they were very difficult to remove from the wound and caused the victim great pain during the process.” A very grim picture, without question. To be struck by an arrowhead with barbs or hooks, poisoned with putrefied remains, would indeed be horrific.

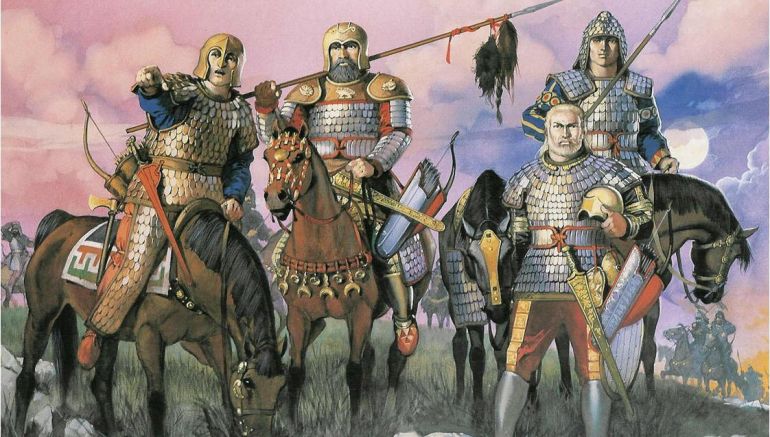

Scythian–ancient nomadic Iranian–warriors on the steppe

With all these different poisons used by the Scythians, they had to know how to tell what was what in their gorytus, or case for holding the bow and quiver of arrows. The length of the gorytas was relatively shorter than the bow itself, leaving the weapon partially exposed. It also had a metal covering for the arrows, most likely to protect the archer from scraping his skin across the poisonous arrowheads.

The Scythians would paint their arrow shafts in the color of red or black, while others had zigzag and diamond patterns decorating them. Not so coincidentally, these various patterns painted upon the arrow shafts were the same patterns found upon the various vipers used by the Scythians as their agents of death. Vipers with a zigzag or diamond pattern upon their backs were the most poisonous of all.

Clearly, the painted design was a way for the archer to tell which poison he was using. Additionally, the decorated arrow shafts, when fired at the enemy, likely had a psychological effect, for they must have looked like snakes flying through the air, while the barbs protruding from the point appeared like fangs to the enemy.

So now that the Scythians had their gorytus, stacked with a fierce weapon and deadly arrows, it was just a matter of choosing which chemical killer to use on the enemy.

By Benjamin Welton

When it comes to Julius Caesar’s accounts of the Gallic wars, it’s clear to see that propaganda was his chief concern. Of course, he claims to have recorded his conquest for the purposes of posterity, namely that his notes would be the source material for a later, more qualified Roman historian. But despite his main motivations, his accounts have, in fact, become one of our most important resources regarding a mysterious peoples.

(The Dying Gaul, or the Dying Galatian, an ancient Roman depiction of a defeated Celtic warrior)

Covering modern-day France, Belgium, and parts of Switzerland and Germany, the Gallic Wars (58-50 B.C.) saw Caesar conquer most of the Celtic world on the Continent.

Not only that, but it also included two Roman invasions of Britain, neither of which netted the distant island for the empire. (That, of course, came later in 43 AD under the leadership of the emperor Claudius.) Ultimately, after many years of campaigning and putting down several Gallic rebellions, Caesar crossed the Rubicon in 49 B.C. on his way to winning the civil war for the Populares, or the Roman aristocratic leaders who relied on the people’s assemblies and tribunate for power.

After victory in 45 B.C., Caesar was crowned Dictator Perpetuo and thus the 500-year reign of the Roman Republic imploded, due to the insidious cancers of autocracy and the cult of personality.

In the wider scope of Roman history, Caesar’s political victory was the result of his military accomplishments, especially his success in Gaul. Among his men, Caesar commanded complete authority and trust, and because of this, Caesar’s Commentarii de Bello Gallico – his third-person account of the wars – is replete with examples of Roman courage and prowess in battle.

While these passages are intended to show the brilliance of Caesar’s command, they also serve to highlight something starker – the inferiority of the Gauls (according to Caesar) and the Gallic way of war.

Much like the later Germania by Tacitus, which primarily concerns itself with an ethnographic view of the Germanic tribesmen, who would eventually bring down the Western Roman Empire, Caesar’s The Conquest of Gaul offers up a sociological analysis of a “barbarian” people from the point-of-view of their conquerors.

Sadly, history has only left behind fragments of the Gaulish language, and few, if any, of these documents pertain to the Gallic Wars. In this sense, Caesar’s account of the Gauls is still the best resource for scholars interested in France’s Celtic past.

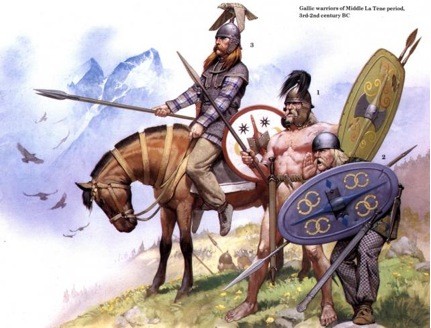

(Modern interpretation of ancient Gallic warriors)

In Caesar’s account, the Gauls are described as somewhat lazy, fiercely independent, and prone to violence, although not as warlike as their Germanic neighbors. In Book VI, Caesar writes:

In Gaul, not only every tribe, canton, and subdivision of a canton, but almost every family, is divided into rival factions. At the head of these factions are men who are regarded by their followers as having particularly great prestige, and these have the final say on all questions that come up for judgement and in all discussions of policy.

Unlike the Germans and the Belgic tribes who were ruled by kings, the Gallic tribes were predominantly ruled by oligarchies composed of warrior noblemen, who are called “knights” in most English translations of Caesar’s text. These Gallic knights acted as magistrates, military leaders as well as serf-holding landowners. In this, they eerily presaged the later feudal system of the medieval period – a system that saw its greatest heights in France, no less.

According to Caesar, the development of the Gallic oligarchies was brought about in order that “all the common people should have protection against the strong.”

Caesar, who came from a family with a history of supporting people’s assemblies and other populist causes, more than likely found this praiseworthy. Throughout his notes he is keen on showing how the Gauls, who had by this time become acquainted with Roman and Mediterranean customs due to trade, differ from the more “uncivilized” Germans.

Caesar’s notes from the Gallic Wars also include some of the earliest descriptions of Gallic religious traditions, especially in regards to the Druids. Long the favorites of horror and suspense writers, the mysterious Druids were the priestly class among the Celts, and as such, Caesar spends some time in describing their manner:

The Druids officiate the worship of the gods, regulate public and private sacrifices, and give rulings on all religious questions. Large numbers of young men flock to them for instruction, and they are held in great honour by the people. They act as judges in practically all disputes, whether between tribes or between individuals; when any crime is committed, or a murder takes place, or a dispute arises about an inheritance or a boundary, it is they who adjudicate the matter and appoint the compensation to be paid and received by the parties concerned.

(A 19th-century engraving of two Druids)

Caesar’s descriptions do not stop there either, for he also claims that the Druids, unlike the common people, were ruled by a single and supreme priest, who either earned the office owing to his merits or was elected to it by his peers. Furthermore, the Druids of Continental Europe looked to Britain as the origin and seat of all Druidic doctrine.

Of all the claims that Caesar’s notes make about Gallic customs, none is more sensational than a single line entry concerning human sacrifices:

As a nation the Gauls are extremely superstitious; and so persons suffering from serious diseases, as well as those who are exposed to the perils of battle, offer, or vow to offer, human sacrifices, for the performance of which they employ Druids. They believe that the only way of saving a man’s life is to propitiate the god’s wrath by rendering another life in its place, and they have regular state sacrifices of the same kind. Some tribes have colossal images made of wickerwork, the limbs of which they fill with living men; they are then set on fire, and the victims burnt to death (emphasis mine).

This horrendous image of a colossal wicker man filled with living humans bound for a fiery death is arguably the most culturally important image in The Conquest of Gaul. Specifically, Caesar’s brief description of a certain type of human sacrifice practiced by the Gallic tribes inspired not only a 1967 British horror novel by David Pinner, but also a whole genre of cinematic horror – Mark Gatiss’ “folk horror.”

Chief among these films is Anthony Shaffer’s The Wicker Man. A strange, disturbing film about an isolated pagan outpost in the Scottish Hebrides, it has helped like none other to popularize Caesar’s text, which before had been mostly known for its exemplary use of unadorned, straightforward Latin.

Some historians and classicists may cringe at the idea that Caesar’s account of his campaigns in Gaul has primarily inspired horror movies as well as Astérix, René Goscinny’s beloved comic series about a village full of lovable Gauls.

However, it remains that his writings and descriptions allow for such inferences, because despite the many discussions concerning military tactics and battlefield politics, The Conquest of Gaul is a stylized portrait of a peculiar people. Moreover, because the Gauls, along with their Celtic brethren on the Continent, still remain enigmatic, the opportunities for speculative interpretations are many.

This mixture of fact and fiction is at the core of Caesar’s account and since few popular representations of Gallic and/or Celtic paganism can escape Caesar’s text, it still remains that The Conquest of Gaul is the seminal, yet biased authority on all matters Celtic. So perhaps in spite of Caesar’s best propaganda efforts, he still left an important historical reference.

By Benjamin Welton

Tacitus’ ethnographic work, Germania (98 AD), caused quite a stir among the Renaissance’s numerous intellectuals when it was rediscovered in 15th century Italy. This is because it provided a lengthy history of Europe’s deep divide between what was considered Roman and “non-Roman.” After all, it was once believed that the Germanic peoples—the very “barbarians” who caused the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD—were responsible for Europe’s bleak age of ignorance, savagery, and constant warfare.

These longhaired and bearded peoples had only been lightly touched by Greco-Roman culture, and, as a result, they remained mired in their tribal affinities and cold superstitions.

But this once common view has fallen out of favor in recent years, due to a renewed interest not only in the foibles of Rome’s imperial culture, but also in the overlooked accomplishments of the so-called “Dark Ages.” Author of “Why the so-called ‘Dark Ages’ were just as civilized [sic] as the savage Roman Empire,” Dr. Dominic Selwood laments how it is popularly believed that “the ‘glory’ of Rome was ruthlessly snuffed out, trampled under hooves that sought only plunder.”

Worse still, these defilers of culture are often misrepresented as “boorish hordes” who propelled Europe backwards rather than forwards.

It is Dr. Selwood’s assertion, however, that these Germanic raiders were little different from their Roman opponents, as “violence and ruthlessness” were the primary pillars upholding imperial Rome. In order to back-up this grand claim, Dr. Selwood points to Tacitus’s Annals (14-68 AD), which provides a graphic depiction of the Roman army’s utter destruction of the druids on the Welsh island of Anglesey:

Reassured by their general, and inciting each other never to flinch before a band of females and fanatics, they charged behind the standards, cut down all who met them, and enveloped the enemy in his own flames.

Of course there is little doubt among historians—both amateur and professional—that ancient Rome was a warlike power. One does not capture most of the known world through diplomacy alone. And so, it is not shocking that a society that originally built itself upon its martial prowess would see little wrong with the occasional slaughter.

Still, the fact remains that Tacitus, a senator, historian, and lifelong bureaucrat who is most famous for his often pessimistic histories, is the predominate Roman scholar used in the service of dissecting the mythology of Rome.

The reasons for this are many, but chief among them is the well-known fact that Tacitus was repulsed by imperial Rome’s slip into decadence. Like the much later British historian Edward Gibbon, Tacitus bemoaned the decline of the virtues of the Republican era. In particular, he disliked imperial Rome’s acceptance of debauchery, from orgies to rampant infidelity. In the conservative tradition of Cato the Elder, Tacitus believed that Rome was rotting from the inside due to its easy acceptance of the Greek philosophies of Hedonism and Epicureanism.

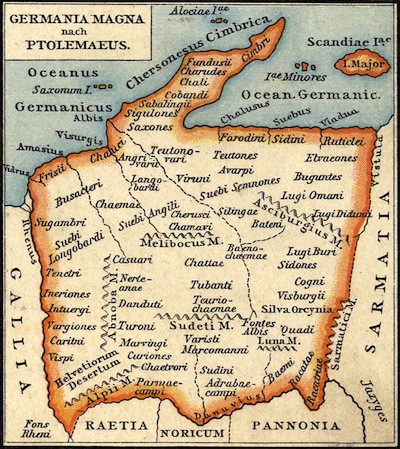

In Germania, Tacitus juxtaposes the morals of the Germanic peoples with those of Rome.

During the time of Germania’s construction, the Roman Empire stopped at the Rhine, and this served as the boundary between ‘civilization’ and ‘barbarism’. Roman legionaries patrolled this desolate region with stern stomachs, for despite Rome’s technological superiority, the Germanic tribes were widely feared due to their supposed love of battle and their fierce bravery.

Roman soldiers also knew well the story of the Teutoburg Forest—the scene of the decisive ambush that destroyed three Roman legions. The Battle of Teutoburg Forest effectively halted further Roman expeditions into Magna Germania, and as such, Germania is a chronicle of Rome’s most feared and tireless enemy in Europe (the Parthians held that honor in Asia).

Throughout his account, Tacitus, who is mostly concerned with an itemized account of the major and minor tribes of western Germany, constantly refers to the virtues of the Germanic tribes—they are large, strong people who are faithful to their wives and they allow only the best among them to rule. In Chapter 18, Tacitus writes favorably about Germanic marriage laws, all the while quietly criticizing the indecent practices of his own Rome:

Their marriage code, however, is strict, and indeed no part of their manners is more praiseworthy. Almost alone among barbarians they are content with one wife, except a very few among them, and these not from sensuality, but because their noble birth procures for them many offers of alliance.

Tacitus also details how Germanic wives are reminded during their wedding ceremonies that they are bound to share the sufferings of war, alongside their husbands. This spirit of mutual allegiance and courage is especially vaunted by Tacitus.

But the real thrust of Germania is this: it is partially a politically-minded critique of Roman society that uses the Germanic barbarians as a counter-example, while at the same time upholding Roman civilization as the one culture that undertakes war and adventure for more complex reasons than simple rites of passage.

Conversely, although Tacitus is often looked upon as the most cynical of Roman historians, he nevertheless maintains the superiority of the Roman Empire in each one of his histories.

Then in a strange twist, Germania became a favored book among the nascent German nationalists of the nineteenth century.

As Christopher Krebs shows in A Most Dangerous Book: Tacitus’s Germania From the Roman Empire to the Third Reich, German nationalists and their coterie of militarist partisans used Germania to testify to the moral superiority of the ancient Germanic peoples. These writers, politicians, and agitators saw in Tacitus’ account a clear history of the otherwise little known pre-Christian Germanic peoples, as well as definitive indication that Germanic culture was separate from and relatively untouched by Greco-Roman culture.

This, of course, was used to justify all sorts of goals, from the eradication of democracy (which originally came from Athens) to state-sponsored mythologies that idolized the totems of a pagan past.

By the 1930s, National Socialism attached itself to these popular misconceptions, and again Tacitus was misused in the name of anti-Semitism and needless warfare. In a blunt example of the book’s power, the SS were ordered to an Italian villa in 1943 for the sole purpose of retrieving the oldest copy of Germania ahead of the approaching Allies.

Sadly, some movements still read Germania as an unwavering example of Germanic superiority, from Neo-Nazis to Scandinavian musicians on the fringe of the “black metal” music scene. Clearly, this mistake comes from a misreading of Tacitus, who, despite his reservations, was a thoroughgoing Roman who was deeply proud of the accomplishments of his people.

Furthermore, Germania was not written for Germans but for Roman citizens—the people who earnestly believed that their culture could be adopted across the world (a lesson they learned from Alexander the Great).

In another cruel irony, the people who mistake Germania as a paean to the glories of Northern Europe’s pre-Christian past also overlook the historical fact that the Germanic tribes who caused the downfall of the Western Roman Empire were themselves Christian—a religion they adopted after their prolonged exposure to Greco-Roman culture.

By any stretch of the imagination, the men who sacked Rome were well versed in Roman culture, especially since many of them were veterans of the Roman army. And by the time of the “Dark Ages,” the people most responsible for keeping Greek and Roman learning alive in Europe were the Franks—a Germanic tribe who had once been knocking at Rome’s imperial border.

It appears then that the old lines between civilized and barbarian, Roman and Germanic were more than a little blurred.

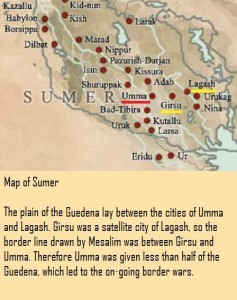

It’s around 2430 BCE in ancient Mesopotamia and Eannatum, King of Lagash, is in the midsts of establishing the first empire in history through constant warring.

One would think that Eannatum’s early military campaign would have begun by attacking the city-state of Umma, due to their previous disputes over the border and waterways. However, instead of going straight for Umma, Eannatum turned his attentions to the Elamites. There he “conquered Elam” and ripped up their “burial mounds.”

But why did Eannatum’s tour start with Elam? Well, the Elamites were a troublesome hill people, and in many ways they were still partly nomadic at the time. In other words, they had moved past being hunter-gatherers and had established a civilization like those living in Mesopotamia. However, they still clung to nomadic methods of warfare such as raiding.

An example is the destruction of Ur, which came much later. The actions of this event are found in The Lament of Ur, which states, “Enlil brought down the Elamites, the enemy, from the highlands … Fire approached Ninmarki in the shrine of Gu-aba. Large boats were carrying off its silver and lapis lazuli.”

This type of pillage-and-run tactic likely became monotonous to those living nearest to them. Additionally, Eannatum saw an economic opportunity in subjugating Elam.

He was confident that his military forces could protect Lagash while the main body was sent to conquer and confiscate the lands of Elam, which was rich in timber, precious metals, and stone. Eannatum’s take-over of Elam gave him the resources needed to provide for an army on the march.

Of Elam’s natural goods, one sticks out as a major attraction to Eannatum… tin, which could be found in mines that dotted the Zagros Mountains. Tin was more rare than copper and an essential ingrediant. Without tin to accompany the copper, the manufacturing of bronze weapons was impossible.

Of Elam’s natural goods, one sticks out as a major attraction to Eannatum… tin, which could be found in mines that dotted the Zagros Mountains. Tin was more rare than copper and an essential ingrediant. Without tin to accompany the copper, the manufacturing of bronze weapons was impossible.

Not only did Elam produce its own tin, although how much they produced is uncertain, they also had valuable trade routes that ran through the region from the east. In fact, the mining and transportation of tin went beyond the Iranian plateau. These were all attractive features for the King of Lagash.

Next for Eannatum was the city-state of Urua, located in the northwestern Iranian province of Khuzistan and within the vicinity of Elam. The importance of conquering this city-state was due to its strategic postioning. Urua was on the Susiana plain, which controlled the passage that lead into what would be later become the southern portion of Babylonia.

Finally Eannatum went after his long-term enemy, Umma. As mentioned previously, Umma held an advantage over Lagash due to the bordering Shatt al-Gharraf waterway. By conquering Umma, Lagash had sole control over the waterway that filtered in from the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Furthermore, Lagash at last possessed the fertile fields of Guedena.

Eannatum’s tour of Elam, Urua, and Umma paid off. Eannatum now had provinces and regions rich with resources, including metal to produce weapons and fertile fields to grow food, both of which were used to feed and arm his forces.

But Eannatum was far from finished.

But Eannatum was far from finished.

With an increase in resource-rich lands came an increase in manpower to replenish and increase the size of his ranks. Eannatum was drunk with power and looked west to quench his thirst.

With his eastern flank secured, the west was ripe for the taking. Eannatum led his forces to the city-state of Uruk, which was important for a number of reasons. The first was that Uruk sat along the Euphrates River and was not far from the Persian Gulf, making it a valuable trading city by both land and sea. Second, Uruk’s population was rather large and prosperous, fed by the surrounding fertile fields. This meant Uruk was desirable in terms of supplying the army with food and swelling the ranks with additional troops.

With Uruk conquered, Ur came next and its armies were put to the sword. Ur was also a valuable trading center, and like Uruk, offered a strategic location near the mouth of the Euphrates River that led into the Persian Gulf, which was used for importing and exporting resources.

At this point, Eannatum’s empire was flanked by three natural barriers: the Zagros Mountains to the east, the dessert to the west, and the Persian Gulf to the south. Eannatum’s only true threat now came from the north.

And so, Eannatum made his way north, eyeing the prize worthy religious target known as Kish. However, this time, things weren’t so simple. Zuzu, the king of Akshak, had enough of Eannatum’s war making and went out to confront the man who wished to own the world.

And so, Eannatum made his way north, eyeing the prize worthy religious target known as Kish. However, this time, things weren’t so simple. Zuzu, the king of Akshak, had enough of Eannatum’s war making and went out to confront the man who wished to own the world.

Zuzu, along with his forces, faced Eannatum and his army and a battle commenced. Eventually, Zuzu was killed in combat and his city-state of Akshak taken and incorporated into Eannatum’s ever increasing empire. With Akshak conquered, Eannatum marched into Kish with ease.

Eannatum, confident in his power, decided to take the title “King of Kish.” This names means much more than being the overlord of Kish. It implies that whoever has it, is also King of all of Sumer.

You would think that Eannatum would have been happy with his conquests, since he was now considered the king of Sumer. However, war is the health of the state and that rang true for Eannatum. Soon after Eannatum had taken over and centralised all of Sumer under his sole authority, city-states outside the sphere started to look attractive.

And so Eannatum’s empire continued to grow.

“Eannatum The Conqueror” was written by Cam Rea