By Ben Potter

This was none other than Publius Terentius Afer, better known simply as Terence.

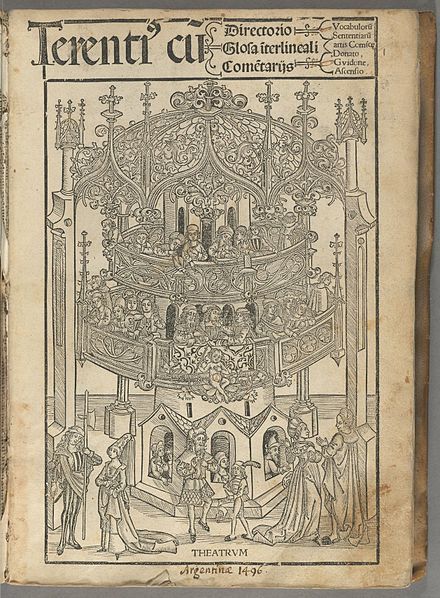

Though Terence was a fine artist and innovator in his own right, there is a similarity between he and Plautus that cannot be ignored… both were comedic playwrights who adapted Attic comedy and presented it to the Roman masses.

But despite this shared penchant for pilfering (they called their works fabulae palliatae – ‘dramas in Greek cloaks’), there is much that is dissimilar about the two men; not least their origin, trials and tribulations.

For instance, Plautus was a well-educated Italian, though he did have his fair share of mishaps and setbacks. Terence, meanwhile, is able to boast a story that is not merely rags, but restraints-to-riches.

He does not quite have the claim of being the first slave to become a successful writer (that gong goes to Aesop), but he may have been the first African to make headway in the field.

However, this is little more than a calculated assumption from the fact that his cognomen, Afer, means ‘the African’.

Suetonius, writing some 200 years after the fact, confirms that Terence was born in Carthage. However, he cannot be viewed as a wholly reliable source, even though we have no reason to doubt his sincerity.

Other speculations consider that he could have been Libyan rather than Carthaginian, as the term Afri would not have been used to denote a Carthaginian at this time.

Less popular are the suggestions that he hailed from one of the towns of Magna Grecia, the Greek colonies of Southern Italy and Sicily. This idea, as well as being considerably less romantic, does nothing to account for the ‘Afer’.

Regardless, it is universally accepted that he was brought to Rome in the thrall of the senator Terentius Lucanus, thus accounting for his nomen, ‘Terence’.

The senator ensured Terence received an education, a surprisingly common deed in those days. However, the senator also performed a very atypical act; he granted freedom to Terence, even though he was seen as a valuable piece of property. This was even more exceptional when considering that he was still relatively young. (It was more often done after a lifetime of service, or upon the master’s death).

Freedom was most probably granted here because Terentius was impressed by the young man’s artistic talents and he didn’t want to stand in the way of a potentially glittering career.

And glittering, though brief, it indeed was.

Brief because he died at sea on his way to Greece, either at the tender age of 35, or the positively raw age of 25!

And glittering because Terence is in an elite group of ancient writers who have their entire canon preserved, intact.

The fact that this opus consists of only six plays does not detract from the fact that his work demands considerable respect.

Though it appears respect was precisely what Terrance was hoping to achieve… And we know this because of his innovative use of the prologue.

Unlike Plautus and his Greek forebears, Terence didn’t do anything as crass and vulgar as to give essential contextual information. Indeed, he was a staunch believer in letting the audience work things out for themselves:

“Do not expect the plot of the Play; the old men who come first will disclose it in part; a part in the representation they will make known”

So what was the purpose of a prologue, if not to “lay our scene”? Why, to rebuke one’s critics of course:

“He [Terence] is wasting his labor in writing Prologues, not for the purpose of relating the plot, but to answer the slanders of a malevolent old Poet”.

Terence certainly had a unique approach to the prologue, a trait that differentiates him from Plautus; one, in fact, of many.

Another was Terence’s conversational and realistic dialogue. It is thought that he may have been the man to create the dramatic use of the ellipsis, those little dots that nicely hint at a missing word, such as….

Indeed, his characters are far less prone to wallow in the cunning punning or absolutely arbitrary amounts of alliteration found in Plautus.

This, together with the fact that he was loath to break the fourth wall, has led to Terence being dubbed ‘the father of Sitcom’!

However, if his works were to be considered sitcoms, then they could only be HBO ones. No G rating for this Roman.

While his choice of subject matter is one of the most interesting things about Terence, there are moments when he skirts the boundary of what is now, and perhaps was then, good taste.

The Hecyra, for example, shows a newly minted marriage thrown into jeopardy when it turns out the bride is pregnant as the result of a rape she suffered before the wedding. But all turns out for the best in the end when it materializes that, unbeknownst to all, the groom was the rapist all along!

Of course, it is difficult to gauge just how much tastes have changed.

It is possible that the plot line was tolerated mainly because the play was set in Greece, a supposedly decadent foreign land in which rape was taken with a pinch of salt. That said, Terence does deal with the topic with greater sensitivity in Eunuchus.

There are also times when he focuses on the dynamics of the father/son relationship, generating a good deal more empathy than in some of his other tales.

Even though it seems his plays were enjoyed by the masses, Terrence was not rightly appreciated as an artist until after his death.

Within 100 years of his premature demise, Terence had become a set text for all Roman schoolboys.

His place on the curriculum was retained throughout European schoolrooms until the nineteenth century, as he was regarded as the perfect conduit through which to study Latin.

In fact, the Catholic church may have done its fair share to keep Terence’s works alive, as it was a necessity to learn Latin for mass and bible study. His plays were often chosen because they were popular and approachable texts… and perhaps a bit more entertaining than endless psalms.

Though, curiously, Terence’s most quoted line:

“homo sum, humani nil a me alienum puto” – “I am a man, I regard all that concerns men as concerning me”

….has been misappropriated as a piece of sagacious philosophy. In fact, it was originally put into the mouth of a nosy neighbour looking to justify his own snooping!

Nonetheless, the view of Terence as a fine and noble scholar, one worthy of our attentive consideration, is espoused by that fine man of letters, President John Adams. It is to him that we shall give the last word as to why Terence was, is, and always will be of interest to those with classical or literary interests:

“Terence is remarkable, for good morals, good taste, and good Latin…His language has simplicity and an elegance that make him proper to be accurately studied as a model”.

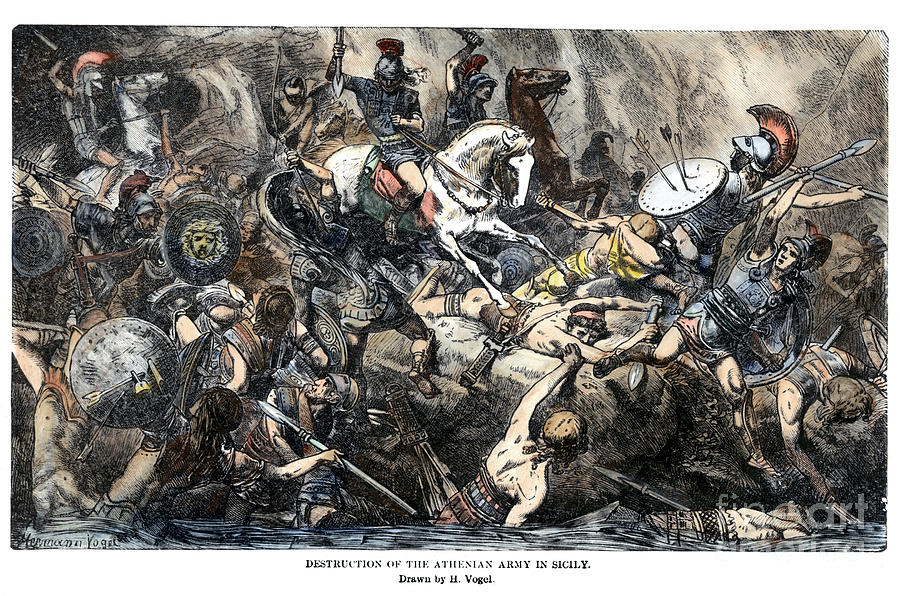

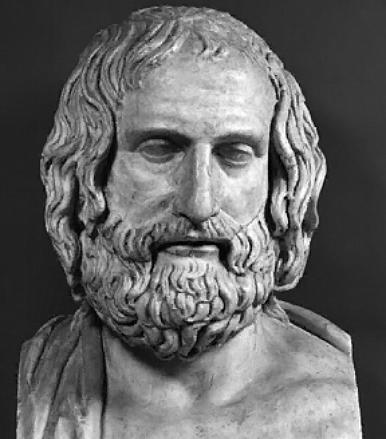

A lone figure, swaddled in rags sits secluded in a dank cave bent over his papyrus. The whittled reed in his hand dips rhythmically into the pot of octopus ink before adding a couple of urgent scratches to the thick page. His bushy, white beard is stained off-centre at the lower-lip, evidence of his habitual pen-chewing; but it is his mind, his mind that is stained far more indelibly. There are images of gods, war, warriors, adultery, incest, exile, blasphemy, damnation, infanticide, patricide, matricide, human-sacrifice, and worst of all, foreigners. These are the ideas, the dark and evil components of Greek tragedy, that this man, this Euripides believes are too… too… stock, too trite, too bedtime-story for the citizens of Athens. He knows that beauty is terror. “Whatever we call beautiful, we quiver before it.” (Donna Tartt)

A lone figure, swaddled in rags sits secluded in a dank cave bent over his papyrus. The whittled reed in his hand dips rhythmically into the pot of octopus ink before adding a couple of urgent scratches to the thick page. His bushy, white beard is stained off-centre at the lower-lip, evidence of his habitual pen-chewing; but it is his mind, his mind that is stained far more indelibly. There are images of gods, war, warriors, adultery, incest, exile, blasphemy, damnation, infanticide, patricide, matricide, human-sacrifice, and worst of all, foreigners. These are the ideas, the dark and evil components of Greek tragedy, that this man, this Euripides believes are too… too… stock, too trite, too bedtime-story for the citizens of Athens. He knows that beauty is terror. “Whatever we call beautiful, we quiver before it.” (Donna Tartt)