Written by Ed Whalen, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

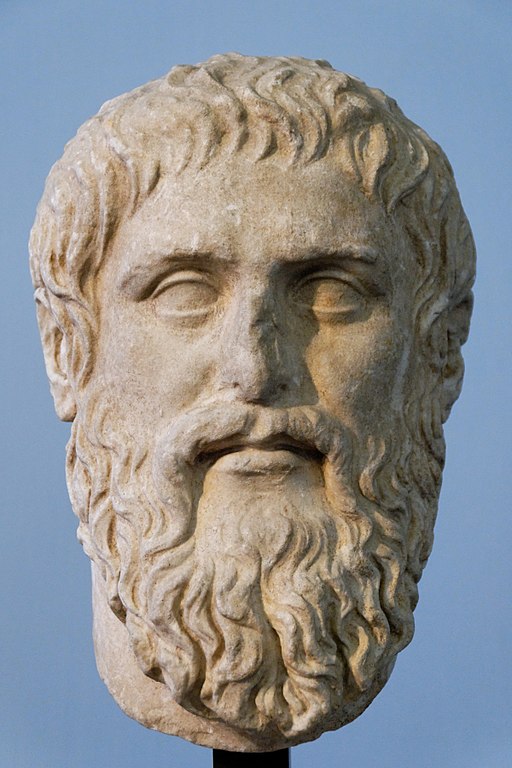

Plato is regarded by many as the world’s greatest philosopher. In his dialogues, he examined everything from the nature of reality, to ethics, to beauty, to the state. The Symposium, which you can read in full here, is the summation of Plato’s ideas on love, and have proven very influential.

The main character in the dialogues is the great philosopher Socrates, who inspired Plato. Scholars have been trying to understand for centuries which of the ideas expressed in the Platonic dialogues are Plato’s and which are Socrates’.

The Symposium

The Symposium was named after the cultural and social practice of the same name, which was a post-banquet gathering in which men would drink, listen to music, and relax. Typically, there was a great deal of conversation and witty talk. Guests would drink too much and would say things they would never say. The events portrayed in the Symposium dialogue took place in 385 BC. In the text, there are seven speakers, all based on historical characters.

Characters in the Symposium

It is important to understand the characters in the dialogue in order to understand the philosophical arguments put forward by Plato.

Phaedrus was an Athenian aristocrat and a friend of Socrates. Pausanias was a legal professional and Eryximachus was a physician. The great comic playwright Aristophanes was also present at the banquet.

The host of the banquet was Agathon, a tragic playwright. Socrates is also present, as is Alcibiades, the notorious Athenian politician and general who played such a prominent role in the Peloponnesian War. They all offer different definitions of Love.

The speeches

Like all the Platonic dialogues, the work, which is very literary, consists mainly of speeches. Socrates arrives at the party late because he had been lost in contemplation. Agathon invites his guests, to make a speech in praise of love.

Phaedrus goes first. He quotes some poets and argues that Love was the first of the gods and promotes excellence and goodness in people. He argued that there is also a lower sort of love, one based on desire and sexual gratification. Then there is a kind of divine love which involves a lover teaching his beloved virtue and wisdom.

Next spoke the doctor, Eryximachus, who says love is moderation and balance.

Next up is Agathon, who gave an elaborate speech arguing that love is the youngest of the gods. The object of love, according to Agathon, is nothing less than beauty.

Socrates then spoke. He disagreed with Agathon, stating that he mistook the object of love with its intrinsic nature. He then told the following story: He once met a wise woman, who called herself Diotima. Love was a spirit, Socrates learned, that helped us to attain what we desired and needed. It is a spirit or daimon and it mediates between the gods and men, reproducing itself either through the birth of new beings or new ideas.

Socrates held that the world of the senses is based on Forms which exist in an eternal realm. Thus, love is the desire or spirit which lifts the human soul to the knowledge of the Forms.

The Forms were the essence of things from which flow what we perceive as reality; they are called ‘ideas’ in some translations. One of the most important Forms was the form of beauty, and Socrates said love can guide a person to its contemplation.

He showed how love can help the human mind ascend to a higher, eternal realm, one beyond the temporal world of the senses.

At this point, the notorious Alcibiades, who is very drunk and rowdy, butted in. He interrupted everyone to tell them how he tried to seduce Socrates.

In Ancient Greece, sexual relationships between males were tolerated, and those between an older man and a younger man were considered praiseworthy. Alcibiades’ story showed that Socrates had no interest in sexual pleasure. The party becomes chaotic and disorderly. Soon everyone passed out, except the philosopher, who left and went about his business.

Platonic Love

The Symposium is very important in the philosophical tradition. In the work, Plato rejected the idea that love is about desire and sexual gratification. However, many of the speeches make valid points about love, and each one can be seen as taking us nearer the truth.

For Socrates, love was a spirit that helps a person better understand the fundamental nature of reality, or Forms. In the dialogue, Plato, vis-a-vis Socrates, argued the highest love is the philosopher’s love of the truth, contained in the Forms.

This love of the truth is what distinguishes the philosopher. This is what is known as Platonic Love: a love that unites souls by uniting them with the truth.

Conclusion

The Symposium is among the most beautiful of the philosophical dialogues written by Plato, and it is very readable. It is one of the most important texts on love, and it provides insight into Plato’s philosophical system.