Written by Lydia Serrant, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

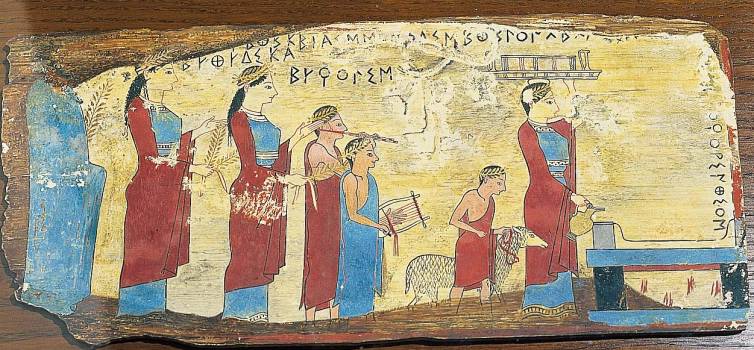

Women had limited mobility in ancient Greek society. They could attend public speeches, certain festivals, and sanctuaries, but otherwise, women were expected to spend most of their time in the gynaikon, the female-only quarters usually located on the upper floor of the house.

From there, women were expected to undertake a strict set of tasks, such as fetching water from the well, managing the household, and weaving fabric. The daily lives and experiences of Greek women are therefore shrouded in mystery. What we do know about ancient Greek women is mostly written from the male perspective, but it is clear they spent large portions of their lives isolated from general society.

Accounts of women who pushed beyond these boundaries give us a but a glimpse of the female contributions to the ancient world. For example, accounts of female painters in ancient Greece are rare and short – and therefore of immense value.

While Greek women with means were known to donate or commission great works of art, not much evidence survives of Greek female artists. The scarcity of such accounts is further evidence of the social restrictions placed upon women in the ancient world.

Kora of Sicyon (650 BC)

Kora of Sicyon is considered the first female painter of ancient Greece, or at least the first recorded female artist of the time.

Kora is believed born between 700 – 601 BC and was the daughter of the sculptor and potter Dibutades. She is mentioned by Pliny The Elder in his Natural History (AD 77), where she is described to have painted the shadow of the face of her lover. Her father later filled this in with clay, resulting in one of the first clay reliefs. The relief was preserved as a gift to the city of Nymphaeum until the Romans sacked Corinth in 146 BC.

Anaxandra (228 BC)

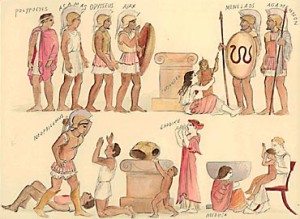

Anaxandra was known for painting icons and figures from Greek mythology. She learned from her father, Nealkes, a painter who was known for saving famous artworks from destruction after the liberation of Sicyon in 251 BC.

According to Clement of Alexandria, Anaxandra was an active painter in 228 BC and is mentioned in his work ”Women as Well as men are Capable of Perfection”. If the title of his book is to be believed, then it appears that some men in ancient Greece were open to the idea of women participating in artistic endeavors.

However, it is unlikely that Clement knew Anaxandra or her work first-hand, having referenced the lost work of the Hellenistic scholar Didymus as his source.

Irene (or Alcisthene) 200 BC

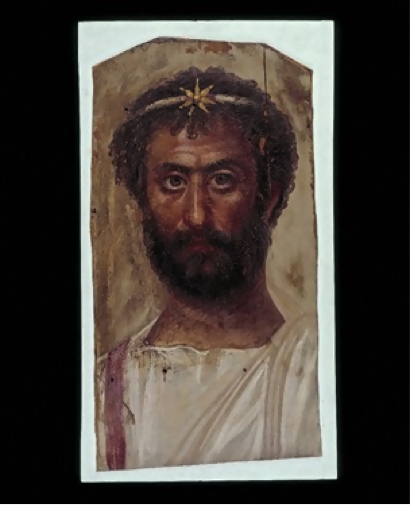

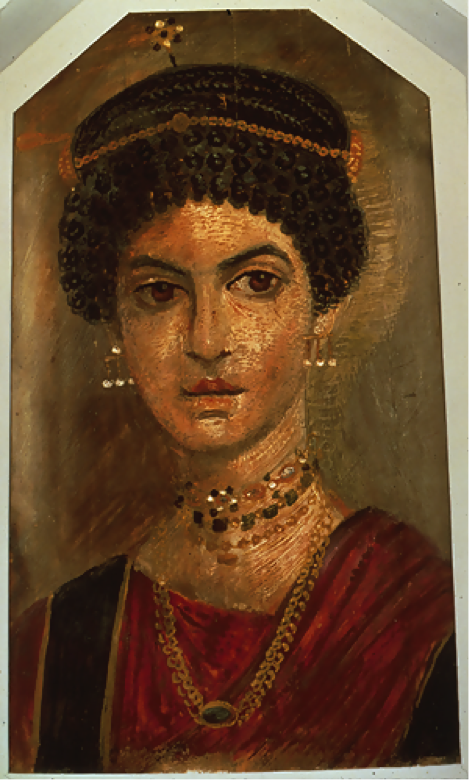

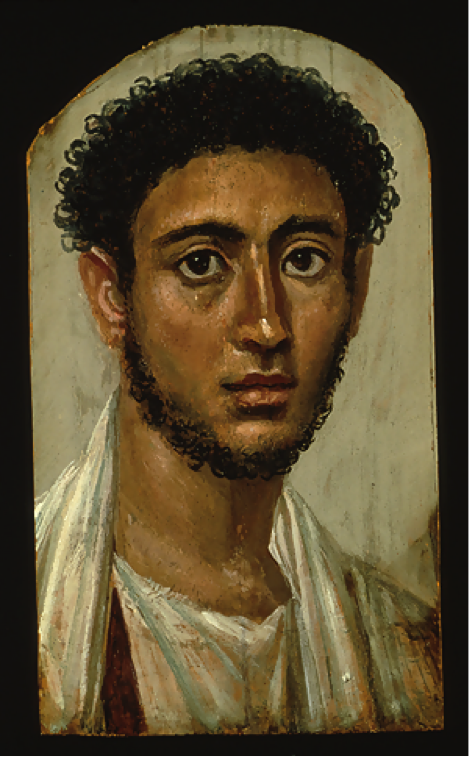

Pliny the Elder was a naval commander and natural philosopher whose works note evidence of female artistic expression. Pliny also writes briefly about Alcisthene (or Alkisthene) who may have been a female painter. However, Latin sources describe her as a dancer, the subject of a painting completed by Irene, the daughter of Cratinus. Irene is noted to have learned her craft from her father, and her paintings are said to be of significance to the Cult of Demeter, Mother Earth, and Goddess of the Corn.

Irene is also credited for painting a portrait of Calypso, the water nymph who imprisoned Odysseus on her island for over a decade. Pliny credits Irene with two other works titled, ”The Old Man” and ”The Juggler Theodores”.

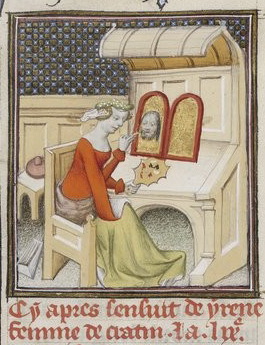

Although Pliny’s descriptions of Irene are brief, and her identity is somewhat confused with Alcisthene, his record of female painters is invaluable. This later became a source of interest and inspiration of Renaissance painters and authors, such a Giovanni Boccaccio, who wrote of Irene:

‘’I thought her work worthy of some praise, since it is very unusual for women, and is not pursued without a high degree of talent, which customarily most rare in them’’

Boccaccio’s comments reflect established societal beliefs about male superiority in Renaissance Italy that extend back to ancient Greece.

Timarete (5th Century BC)

Noted for her painting of Artemis at Ephesus, Timerete is one of the very few Greek female artists of whom we not only have a record of her artistic contribution, but also her feelings about the roles of Greek women in general. Like Irene, Timerete was the daughter of an artist, her father being Micon the Younger of Athens. Micon was known for painting famous battle scenes. Timatete disdained the role expected of her as a woman in ancient Greece, according to Pliny, writing that she “scorned the duties of women and practiced her father’s art.”

Although the roles of women were greatly restricted in ancient times, records from contemporary historians suggest that there were instances of women stepping outside of their expected boundaries to pursue areas of personal interest, even making a name for themselves along the way.

What is evident is that most of the female artists here did have the backing and support of their already famous fathers. It was perhaps the protection and support provided by the family and senior male relatives that enabled these women to challenge traditional gender roles, an advantage that many other Greek women probably did not have. However, thanks to them, the female artistic talent and contribution to Greek aesthetic culture has been captured, albeit minimally.

Although the descriptions of these women are short, the fact that they exist at all is a testament to the determination of Greek women and those that supported them. Finally, it speaks to the impact of feminine artistry on the male-dominant culture of ancient Greece.

References:

Venit, M. (1988). The Caputi Hydria and Working Women in Classical Athens. The Classical World, 81(4), 265-272. doi:10.2307/4350194

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/wmna/hd_wmna.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kora_of_Sicyon

https://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/irene-fl-200-bce

Ridgway, B. (1987). Ancient Greek Women and Art: The Material Evidence. American Journal of Archaeology, 91(3), 399-409. doi:10.2307/505361

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timarete

https://web.archive.org/web/20070405163226/https://www.ancientlibrary.com/smith-bio/0172.html

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/heritage_floor/anasandra