The Historical and Cultural Significance of Olympia

Written by Divya Gupta, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The first Olympic games were held in Athens, Greece in 1896. Around 280 participants from 13 nations competed in 43 sporting games. Since 1994, the famous Game has been held separately as the Winter and Summer Olympics every two years.

But did you know these modern games are inspired by the ancient Olympics in Greece which originated around 3000 years ago! From the 8th century B.C. until the 4th century A.D. these Games were held every four years, between July and September, during the religious festival honoring Zeus.

The Origin of the Olympics

The first ancient Olympic games were held in 776 BC in Olympia, on the first full moon after the summer solstice (around mid-July). The ancient town of Olympia was named after Mount Olympos, though it is nowhere near it. Mount Olympos is the highest mountain in Greece, and in Greek mythology, it was considered as being home to the gods and goddesses, and the Sanctuary of Zeus.

Ruins of the palaestra at Olympia, Greece.

The ancient Olympic game began as a regional religious event and reached the heights of national importance when the Greek empire spread in the 5th century B.C. What was once a friendly and fun-loving event, became a matter of colonial pride!

The winner of the first Olympic Games was Koroibos, a cook hailing from the town of Elis who won the only game, stade (origin of the word stadium). Stade was a 192-meter-long footrace that continued to be the only sport for 13 Olympic festivals.

Olympic Games

Sporting activities were an integral part of Greek education. The athletes would start preparing at an early age by professional trainers who helped them develop muscles, regulated their diet, and taught them sporting techniques.

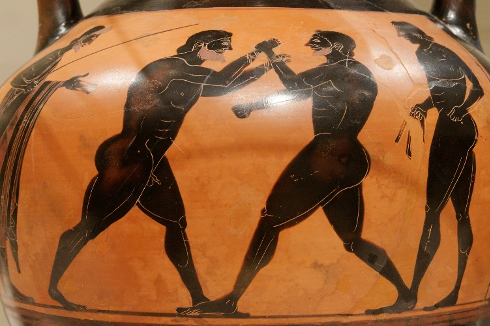

There were many other sporting competitions, but the Olympics remained the most prestigious one. After 13 successful games, two more races were added: the diaulos (around 400-metres race) and the dolichos (a 1500-meters race). In 708 B.C. the very famous pentathlon (a race with five events: a foot race, long jump, discus, javelin throws, and wrestling match) was introduced. Many other games were added through the years like boxing in 688 B.C., chariot racing in 680 B.C., and pankration in 648 B.C.

Space where Olympians would practice boxing and wrestling at the paleastra of Olympia.

The famous Nudist Tell Tale

Legend has it that the athletes would run naked during the competition. Women were prohibited from participating or spectating the games, although young girls were allowed in the crowds. During one of the games, Kallipateira sneaked in to watch her son, Peisirodos, play.

She had trained him rigorously and, after seeing him win, the mother couldn’t contain her excitement and celebrated a bit too much while loosening her clothes. The secret was out! She revealed her sex and soon received a death penalty. But she managed to escape the punishment because her family was home to great Olympic victors. Since then, every athlete had to undergo the training and participate in the events without wearing any clothes!

Olympic Rules and Regulations

Greeks took these games pretty seriously. Every athlete had to report to the events one month before the games and had to declare that they have been training for a minimum of ten months. Non-Greeks, lawbreakers, slaves, and murderers were prohibited from participating. Many cities, including Sparta in 420 B.C., were excluded from the games too.

A relief from a funerary kouros base depicting two Greek wrestlers, one of the sports at such events as the Olympic Games at Olympia. c. 510 BCE. (National Archaeological Museum, Athens)

The Hellanodikai judges from Elis were trained specially to organize the event. They had the power to disqualify and punish participants who infringed the law. On the breaching of any rules, the athlete or the city he represented had to pay hefty fines.

The Participants and Olympic Champions

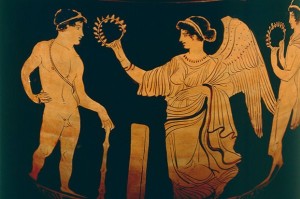

The Hellanodikai judges crowned winners with a wreath made of olive leaves and branches, as a sign of victory. Olive was significant to Olympia because it was planted by Hercules himself. In chariot races, the owners received these olive leaves while the charioteer was gifted a red ribbon to be worn on the upper arm or head. Victors were highly regarded and would often be welcomed to their hometowns with a grand ceremony. Large celebrations were organized in honor of their victory. Olympic winners were considered real heroes and received glory, fame, and historical immortality.

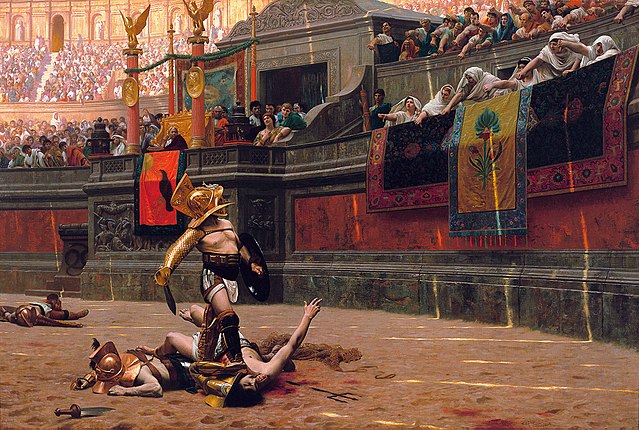

Boxers represented on a Panathenaic amphora. Currently located at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Amongst the famous Olympic champions are Kroton, from southern Italy, and Leonidas of Rhodes. Literary tales also fabricate the story of Roman Emperor, Nero, who would win every game he competed in! The first woman to win a game was Kyniska in 392 B.C. Women were not allowed to participate but they could own a horse and hold a title on its win.

It is speculated that almost 45,000 people would attend these famous games. Food vendors, musicians, and artists would all come together to entertain people. Masses would extend their support with boisterous activities and hooting. No wars were allowed during the period and people would excitedly gather to celebrate the prestigious event.

End of The Ancient Olympics

Around the mid-2nd century, the Roman Empire conquered Greece and eventually the standard and quality of the games fell. In 393 A.D., Emperor Theodosius banned all ‘pagan’ festivals including the famous Olympics. The ancient game lasted for nearly 12 centuries with 293 successful Olympiads before coming to an end.

Resources:

Written by M. Reed Myers, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

If you are like most people, you probably wonder what life would be like if you had the body of a Greek god. You wonder what doors would open for you if you had the kind of physique that only a Praxiteles would be fit to sculpt.

Wonder no more, dear reader. This article presents fitness concepts derived from the best of classical Greek sculpture, pottery, and literature, adapted for us all-too-human moderns.

Read on: adventure and heroic stature await you.

Sing. O muse, and bid your listeners consult with Asclepius before beginning any of these programs.

Think and Thrive

The gymnasia were at the center of ancient Greek physical education. Based on the word-root gymno, meaning “naked,” physical exercise at the gymnasium was done mostly in the nude, under the gaze of gymnastes, or coaches. Because the student’s body was completely observable, the coach could accurately diagnose physical limitations and develop an individualized training plan.

Archaeologists have excavated gymnasia in such sites as Athens, Delphi, Epidarus, Eretria, Olympia, and even Priene in the Greek islands. By the 5th century BC, the gymnasia offered more than just physical training. Students also received basic physical therapy, listened to lectures, watched dramatic presentations, and listened to poetic recitations. All these elements reinforced the overarching Greek culture, with a heavy emphasis on honoring the Olympian gods and semi-divine heroes.

A major problem with this system, of course, was its exclusion of women. Although Spartan women were somewhat freer, no woman in ancient Greece could exercise the same rights and freedoms as their male peers. This is not the case with these exercises. They are designed to exercise the major muscle groups and can be of benefit to either gender.

A common motif in Greek black-figure pottery was the depiction of male figures performing various exercises common to the gymnasium. Think and Thrive is a workout that builds on these art motifs to create a balanced, healthy physique with lower body, core, and upper body elements. As you progress from one exercise to the next, maintain a steady pace. Regarding exercise intensity, you should be able to speak in short sentences, but not dramatic monologues.

You will need a large open field, preferably with an oval or circular track at the perimeter, a frisbee or other throwing disk, and a weighted object you can grasp with both hands (like a kettle bell). At one side of the field, place your throwing disk, on the other side of the field place your kettle bell or other weight.

Strophe: if you are exercising by yourself and have access to audiobooks, listen to a major section of any of the following: the Iliad, Works and Days, or any of the myths of Theseus or Heracles. While listening, jog at a moderate pace around the perimeter of the field and ponder the crucial lessons you are hearing. If you do not have access to audiobooks, ask an exercise partner to chant the section aloud to you, while you jog in a smaller circle around your partner.

Antistrophe: Six sets of the following exercises.

Hurl like Hektor: Hold your flying disk in both hands, with arms extended. With your feet shoulder-width apart, and your weight balanced on both feet, slowly rotate your upper body from right to left, until you reach 100. Throughout, tighten your core and abdomen (as though you were bracing to receive a punch). When you reach 100 rotations, throw your flying disc across the field toward your kettle bell or other weight.

Run like Atalanta: While your flying disc is in the air, sprint as quickly as you can after it. Pick it up on the run and sprint with it back to your starting point. Bonus points if you are able to catch it on the fly!

Panathenaic amphora, a victory prize from ca. 530 BC depicting a foot race, attributed to the painter Euphiletos. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Row like Jason: Before you regain your breath after your sprint, drop your flying disk and lift your kettlebell or other weight. Stand upright with your feet hip-width apart and the weight resting across your thighs. Tighten your abdomen again, pull your shoulders back, lift your chest and keep your lower back in its natural curve. Keeping the weight close to your body, pull upwards while extending your elbows. Lift the weight until it is just under your chin. Slowly lower the weight back to full extension. Breathe in and out throughout the exercise. For the basic exercise, do one repetition for each of the 12 labors of Heracles. For advanced exercise do one repetition in honor of each of the argonauts.

Epode: listen to your selection once again while jogging around the perimeter. Think about the implications of the lesson for your community and for all the Greeks. This workout can be done 3 – 4 times per week, with rest days interspersed. Alternate upper body exercises could include shoulder shrugs rather than upright rows or bicep curl to shoulder press.

The Heraean Games

Greek physical fitness was initially based on the principle that civic survival depended on having physically strong, resilient citizen soldiers. The epitome of this perspective was Sparta.

As the readers of Classical Wisdom know, Sparta’s political relevance in Greece depended on its ability to produce highly disciplined warriors who could simultaneously subdue its helot slaves and intimidate its political rivals.

It is said that when Philip II of Macedon was expanding his control over Greece in 346 BC, he sent an imperious demand to the Spartans, demanding their submission: “If I bring my forces into your land, I will ravage your homesteads, massacre your people, and destroy your city.”. The Spartans are said to have warned him off with one word: “If.”

It is worth remembering that this apocryphal encounter would have taken place about a generation after Sparta’s forces were soundly defeated by Thebes in the Battle of Leuctra (371 BC). Sparta’s diminished reputation alone was still strong enough to unnerve Philip.

One of the surprises in Spartan society was the unique status of elite women. Physical health was considered absolutely vital for the growing girl, because her health affected her ability to bear children for the Spartan state. Towards this end, girls were well fed, were encouraged to exercise, play sports, and to stay physically active throughout life. While Spartan married women did not take part in foot races, they were encouraged to dance and stay physically active.

For this workout, you will need an oval track and sandbag or other weighted sack with handles. Fill it with a weight that challenges you to complete the exercises. This work out is named in honor of the Heraean races, a pan-hellenic race for unmarried Greek women. Although the Heraean games were specifically for females, this work out can be used by either gender.

Strophe: Place your sandbag at the starting point on the track. Then, slowly jog one lap around the open field for each of the kings of Sparta. Then, proceed to forward lunges, to emulate the Spartan running girl statue: hold for 30 seconds per leg. One set for each king. Then, split stretch, as low as you can go; lean forward and hold for 30 seconds. Then, a forward bend stretch for 30 seconds to look down upon the helots.

Antistrophe: for helots, 3 sets; for maidens, 4 sets; for matrons, 5 sets.

Run 1 lap around the track.

Carrying your shield or on it: Placing your feet approximately shoulder width apart, bend forward and hold your sandbag with your arms fully extended and knees slightly bent. Keep your back in its natural curve. As you tighten your core, lift the sandbag with both arms until it almost touches your chest, then slowly lower it. Repeat the lift 8 times. That’s one set.

Run another lap around the field.

At your command: Lift the sandbag across your shoulders, feet shoulder width apart. Hold the sandbag tight against your upper shoulders but not pressing on your neck. Bend forward until your upper body is parallel to the ground. Do this eight times. That’s one set.

No further laps, Sparta has only 2 kings

Uplifting the Spartan warriors: keeping the sandbag on your shoulders, drop into a basic squat, your thighs parallel to the ground. Rise to standing. Do this eight times. That’s one set.

Epode: To cool down, jog around the track twice more. Reflect on the fact that there are eight helots for every one Spartan. This workout can be done 2-3 times per week.

The Himantes of Heaven

No discussion of ancient Greek fitness is complete without mentioning the great sporting/religious festivals of the Classical era. These included the Olympic games, Pythian games, Nemean games, and Isthmian games. Of these, the premier event was the Olympics.

The first Olympics were held around 776 BC and initially consisted of religious festivities to honor Zeus. As Pausanias notes, the games gradually expanded over time to include foot races, horse races, wrestling, boxing, pankration (a type of mixed martial art), chariot races, and the ancient pentathlon (running, jumping, wrestling, and throwing the javelin and discus). Eventually boys were allowed to compete for junior championships in several of the sports.

Among the combat sports, boxing (pygmachia) was perhaps the most celebrated. Major Greek heroes like Theseus, Heracles, and Achilles either boxed or encouraged boxing matches. Even gods got into the sport.

In the Imagenes, Philostratus the Elder recounts the tale of Phorbas, a barbarian king, who controlled a river crossing along the sacred way to Delphi. He challenged all travelers to athletic events and, being a superb athlete, bested them. While they were exhausted, he would kill them and display their heads to terrify other travelers. Apollo, in disguise, came upon Phorbas and in the ensuing boxing match, knocked the wicked bandit out with a single punch, like a bolt of fire from the heavens.

For this work out, you will need no special equipment at the basic level. If you have them, you can incorporate weighted wristbands or light hand weights. Properly thrown, punching provides exercise for the muscles of the legs, hips, sides, back, chest, shoulders and arms. If you breathe out when you punch and reflexively tighten your core, you also strengthen your abdominals and obliques.

Strophe:

Position your body in a fighting stance, that is: turned slightly away from your opponent, the wicked Phorbas. Keep your body weight evenly divided between your front and back leg, and lift onto the balls of your feet. Keep your elbows close to your body.

During the entire strophe, keep your fists up, protecting your face. The boxing gloves so frequently represented in Greek art and literature were the himantes. These were strips of ox hide wrapped around the wrists and knuckles of the boxer. They protected the wrist and knuckles, but also gashed and lacerated the opponent. Apollo’s himantes are more beautiful than garlands, says Philostratus, but when he struck Phorbas’s head, a fountain of blood gushed forth. So, keep your fists up.

Bounce gently on the balls of your feet and at random, quickly take a shuffle step in any direction while keeping your fighting stance. You can throw gentle punches if desired, but your focus is on moving quickly and frequently. Try to move forwards, backwards, right and left randomly. If you have an exercise partner, you can ask him or her to randomly call out directions. Bounce and move for 1 minute for each year between Olympics.

Antistrophe:

During this section of the workout, you will continue to rapidly move while in fighting stance, but you will also throw punches. If you have not done a boxing workout before, you may want to consult with a gymnastes for coaching.

Assume the fighting stance, and bounce on the balls of your feet. Throw 10 quick, light punches with your nondominant fist. Keep gently bouncing on the balls of your feet. You may find yourself rising slightly and leaning forward as you throw your punches. If so, move quickly back into balanced stance. After these 10 jabs, bounce and bounce and reverse your stance (so now your dominant hand is forward), throw 10 jabs with your dominant hand.

Bounce back into your original stance (with nondominant hand forward), now throw punch combinations: a fast, light punch with your front first; then, engaging your body, throw a punch with your dominant hand. Do 20 of this combination.

For the next set, now throw 30 quick jabs with your nondominant fist, then bounce and reverse your stance and throw 30 jabs with your dominant hand.

For the final set, bounce back into your original fighting stance (with nondominant hand forward). Throw 40 punch combinations: a jab with your forward fist, followed by a dominant hand punch that engages the entire body.

Epode: As with all the other workouts in this article, cool down with a slow jog. Jog for at least one minute for each of the four ancient Greek games.

The ancient Greeks well understood the importance of maintaining a healthy mind and a healthy body. And in part, exercises like these were part of the process.

Also importantly, those who lived in the classical world were more physically active than most of us today. Just a simple consideration of how we travel on land from point A to point B confirms it: getting anywhere for most Greeks meant walking; for too many of us today, it means either taking a car or a bus.

To fully incorporate classical fitness into your modern life, look for everyday opportunities to develop muscle power. Look for boulders lying about that you can roll up hill. If you happen to have a young calf at home, lift it every day. As it grows, you too will develop legendary strength.

With these and other workouts based on classical Greece, you too will be the envy of Narcissus or Helen, without their nemeses. And after a hard workout, pour yourself a tall krater of room temperature wine. You earned it.

By Mónica Correa, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Nowadays folks use fast cars and designer handbags to flaunt their wealth. Back in the ancient Greek world, however, owning horses was the ultimate status symbol. This tradition continued during the Roman Empire and indeed, anyone who partook in equine activities was immediately assumed to belong to the elite. Chariot racing was no exception… And while the rich got the bragging rights, it was the drivers, the horses and even the fans that took the risk.

Chariot Racing’s Unknown Origins

Chariot racing was a popular sport for centuries, enjoyed under various governments and leaders throughout the ancient world. Its exact origins, however, are unknown.

We know that the sport existed in the Mycenaean world because of artistic evidence on pottery. Meanwhile, the first literacy reference to a chariot race is in Homer’s Iliad, at the funeral games of Patroclus.

Chariot racing on a black-figure hydria from Attica, ca. 510 BC

According to one legend mentioned by Pindar, a chariot race was said to be the event that founded the Olympic Games. The story goes that King Oenomaus challenged suitors for his daughter Hippodamia to a race. He was defeated by Pelops, who then went on to found the Games in honor of his victory.

However, the sport was actually added in 680 BC and included both four-horse (tethrippon, Greek: τέθριππον) and two-horse (synoris, Greek: συνωρὶς) chariot races, which were essentially the same aside from the number of horses. The tethrippon was considered the most dangerous event at the ancient games and was held in the hippodrome.

While the Romans probably borrowed chariot racing (as well as the racing tracks) from the Etruscans, who themselves borrowed it from the Greeks, Roman legend tells another story. The myth says that chariot racing was used by Romulus just after he founded Rome in 753 BC as a way to distract the Sabine men.

The Charioteer of Delphi, one of the most famous statues surviving from Ancient Greece

Chariot Racing’s Characteristics

Some scholars prefer to differentiate between sport, athletics and spectacle. Chariot racing is considered a spectacle because it is essentially a public performance with an audience.

It’s important to remember that chariot racing was extremely dangerous for both the driver and the horses. Driving a racing chariot required strength, skill and courage, and was rarely done by the owner of the chariot, who was not even obligated to attend to the races. Instead, the driver was usually the owner’s family member or slave. The money won by the driver went directly to the owner of the chariot, although wining could put the charioteer in a different social stratum. In fact, drivers could become celebrities just for surviving. Based on this, we can deduce that life expectancy was not very high.

Chariot race of Cupids; ancient Roman sarcophagus in the Museo Archeologico (Naples). Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection

Chariot Racing’s Teams and Fans

The most exciting part of the race for the audience was the turns at the end of hippodrome, which were dangerous, even deadly. The spectators (which, unlike other activities at the time, also included women) were invited to vocalize their support or disfavor at times. The group solidarity, as well as the resulting factional violence, was probably not so different from modern soccer or football.

According to Tertullian, an early Christian author from Tunisia, there were originally only two teams: Red and White, sacred to summer and winter, respectively. These were eventually doubled, the additional colors being Blue and Green. Each team could have up to three chariots each in a race.

A white charioteer; part of a mosaic of the third century AD, showing four leading charioteers from the different colors, all in their distinctive gear

The Blues and the Greens gradually became the most prestigious factions, supported by emperors and the populace alike. Records indicate that on numerous occasions, Blue against Green clashes would break out during the races. The surviving literature rarely mentions the Reds and Whites, although their continued activity is documented in inscriptions and in curse tablets.

Entertainment for Big Audiences

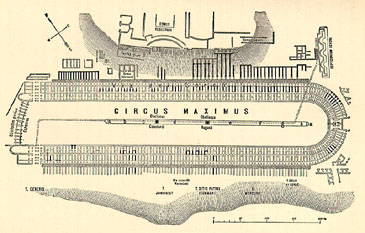

During the Roman period chariot races commonly took place in a circus. The main center, known as Circus Maximus, measured 2,037 ft. in length and 387 ft. in width and could sit 250,000 people. It was the earliest circus in the city of Rome.

The plan of the Circus Maximus

Unlike Greek chariot races, which had 12 laps, a Roman chariot race consisted of only seven turns around the circus. Once the raced started, chariots could move forward no matter what, including purposefully causing extreme crashes, called naufragia. The goal was to weaken the enemy, then beat him.

The design of the chariots was simple: wooden carts with two wheels and an open back. They also used the same style of carts that were used during wars. Unlike other contemporary entertainment activities, the charioteers were always dressed, probably for safety reasons. They wore helmets and sleeved garments that were probably white, according to paintings of the time. Roman drivers wrapped the reins round their waist, while the Greeks used to hold the reins in their hands.

A chariot race during the reign of Trajan. After the painting by Ulpiano Checa, by Granger

Famous Charioteers

Throughout the history of the sport there were a few very famous drivers who achieved a level of celebrity status unparalleled even today. One such celebrity driver was Scorpus, who won over 2000 races before being killed in a collision at the meta when he was about 27 years old.

The most famous of all, however, was Gaius Appuleius Diocles who won 1,462 out of 4,257 races. At the age of 42, Diocles retired after a 24-year career and his winnings reportedly totaled 35,863,120 sesterces ($US 15 billion). This makes him the highest paid sports star in all of history.

Gaius Appuleius Diocles (104 – after 146) was a Roman charioteer, who became one of the most celebrated athletes in ancient history.

The horses could also become celebrities, but their life expectancy was low. Just like fantasy baseball players today, the Romans kept detailed statistics of the names, breeds, and pedigrees of famous horses.

Chariot Racing’s Decline

Chariot racing faded in importance after the fall of Rome. Some records indicate that Nika riots marked the start of its decline. Eventually emperors banned specific sports, including the Olympic games and public entertainment on Sundays, as a way to suppress paganism.

Another important factor was money. With the fall of the Roman Empire, there was no money to invest and no people to entertain.

A winner of a Roman chariot race, from the Red team

While Chariot racing no longer exists in any of its ancient shape or form today, the same culture of fiercely dedicated sport worship, and violence, can be seen today… Fans scream out at trained athletes who compete for honor, status and, of course, money. It shows that perhaps, deep down, the craving for sport entertainment hasn’t evolved that dramatically over time.

By Ben Potter

In a our world where are mainstream sporting heroes are millionaires, prima donnas, sex-offenders, and drug-cheats, the Olympics, can provide countries the world over with real sporting icons, icons worthy of that over- and misused term ‘role-model’.

However, the glory that our gold-medallists enjoy nowadays pales into insignificance when compared to that of the ancient winners.

This was because the games were only open to those from the Greek-speaking world. Moreover, there were merely a handful, rather than hundreds, of events, and it would have been quite likely that the victors would have returned to their pre-fame lives after the games – there were no sponsorship deals on offer then!

This was because the games were only open to those from the Greek-speaking world. Moreover, there were merely a handful, rather than hundreds, of events, and it would have been quite likely that the victors would have returned to their pre-fame lives after the games – there were no sponsorship deals on offer then!

That’s not to say the winners of the Ancient Olympics didn’t enjoy their fair share of recompense. While they were rarely entitled to anything by law, the proud polis would often honor their returning hero with money, food and other such perks.

So, who were these noble competitors who fought to be the greatest physical specimens of The Greatest Civilization? Let’s have a look at some of them, shall we?

1. Coroebus of Elis – the first

A humble cook who grew up near the sanctuary of Olympia, Coroebus was the first man whom we can definitely say was an ‘Olympic champion’. He won the only event at the very first recorded Games in 776 BC – the stadion (which was an approximately 200 meters run).

2. Leonidas of Rhodes – the most prolific

Leonidas was the most successful Olympian ever.

Ever! And I’m including the modern Olympics in that.

Leonidas won the stadion, diaulos (circa.400 meters) and the hoplitodromos (a diaulos carrying 59lbs of armour) at each of the 164 BC, 160 BC, 156 BC and 152 BC games.

These twelve individual first-place finishes (the last of which he achieved at age 36) narrowly surpasses the 11 golds of Michael Phelps. It should be noted that while Phelps did technically win more golds overall, some of those were in relays… and none while wearing battle armour.

3. Diagoras of Rhodes – the happiest

Rhodes’ second favourite son, Diagoras, was considered not only the happiest Olympian, but the happiest man in the world!

Rhodes’ second favourite son, Diagoras, was considered not only the happiest Olympian, but the happiest man in the world!

Descended from heroic royalty, Diagoras won the Olympic boxing crown twice. As if this weren’t enough to raise a smile, his eldest son twice triumphed in the brutal pankration. On the second occasion, in 448 BC, Diagoras’ second son simultaneously triumphed in the boxing.

Hoist aloft on the shoulders of his progeny, a wag in the crowd called out “Die, Diagoras; you will not also ascend to Olympus”. The humour of which was probably only appreciated later, as Diagoras promptly dropped dead on the spot.

4. Astylos of Croton – the saddest

A runner of great renown, Astylos was a highly controversial figure.

The reason being that, after bringing honour to Croton in the games of 488 BC, he turned-coat and, in 484 BC and 480 BC, decided to run for the rival Sicilian city of Syracuse.

His statue in Croton was destroyed, his disgraced family disowned him and his former lodgings were thought unworthy of a free man and were transformed into a prison.

The greatest sprinter of the 480s died a lonely exile, far from his family and friends.

5. Milo of Croton – the most impressive

Unlike Astylos, Milo was someone of whom Croton could really be proud.

Milo won five Olympic wrestling crowns consecutively between 536 – 520 BC.

Milo won five Olympic wrestling crowns consecutively between 536 – 520 BC.

Amazingly, these gongs may not represent the greatest achievements of Milo’s life.

He was said to have led a successful military assault against Sybaris in 510 BC and to have saved the life of Pythagoras (yes, THAT Pythagoras) by holding up the roof of a collapsing building. Consequently, he was given the mathematician’s daughter’s hand in marriage.

Less important, but no less impressive, are his alleged feats of strength and appetite.

He was said to have carried a bull on his shoulders before killing, cooking and eating the entire beast. Though this was perhaps excessive, his normal daily diet was 20 lbs of meat and 20 lbs of bread all washed down with 12 bottles of wine.

And completely uselessly, though again impressively, he was able to burst a headband simply by swelling the veins on his temple.

As so often happens with a unbelievable life, Milo suffered a unbelievable death, he was eaten alive by wolves because his hands were stuck in a tree trunk.

As so often happens with a unbelievable life, Milo suffered a unbelievable death, he was eaten alive by wolves because his hands were stuck in a tree trunk.

There is something deeply impressive and stirring about the achievements of all these citizens. They pushed their bodies to the extremes for the guarantee of no more corporeal gain than a crown of olive leaves.

However, like gallant generals, evocative poets and quixotic politicians, what they were truly yearning for was neither gold or even praise, but immortality. And although such a thing cannot realistically be attained by any man in any field, the fact that their names ring clear and true 2800 years after the event means their ‘athl’, their labours and suffering, cannot be said to have been in vain.