Written by Ed Whalen, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The Ancient Greeks produced many artistic masterpieces, especially in sculpture. Many have survived down to the modern age. Most of the world’s leading museums have some examples of Hellenic sculpture. The iconic Artemision Bronze is one of the most famous surviving pieces of Greco-Roman art—and it has a fascinating story.

The Discovery of the Artemision Bronze

The bronze was found in the waters of the Cape of Artemision on the island of Euboea, which is in the Aegean and just off the coast of mainland Greece. It was uncovered in a shipwreck and recovered from the sea in 1928. Also found in the general area was another famous bronze called the Jockey of Artemision. However, exploration was halted for many years after a diver died at the site.

It has been established that the figure came from a shipwreck that dates to the 2nd century BC. Scholars have speculated that the artwork was being transported back to Rome. Historic sources say that after the Romans conquered Greece, they sent many masterpieces to Italy. Many academics have attributed the piece to the 5th century BC.

The sculpture is in a style known as the Severe Style, which came out of the breakdown of the Archaic tradition and the emergence of the Classical style. Many believe that it was made by the great sculptor Kalamis (Calamis), thought to be an Athenian who worked principally in Asia Minor. Another possibility is that one of the students of Kalamis made the Bronze. Some scholars have argued that the piece was created by Miron, another famed sculptor, but no one knows for sure. It is not known who commissioned the piece or where was it displayed.

Description of the Artemision Bronze

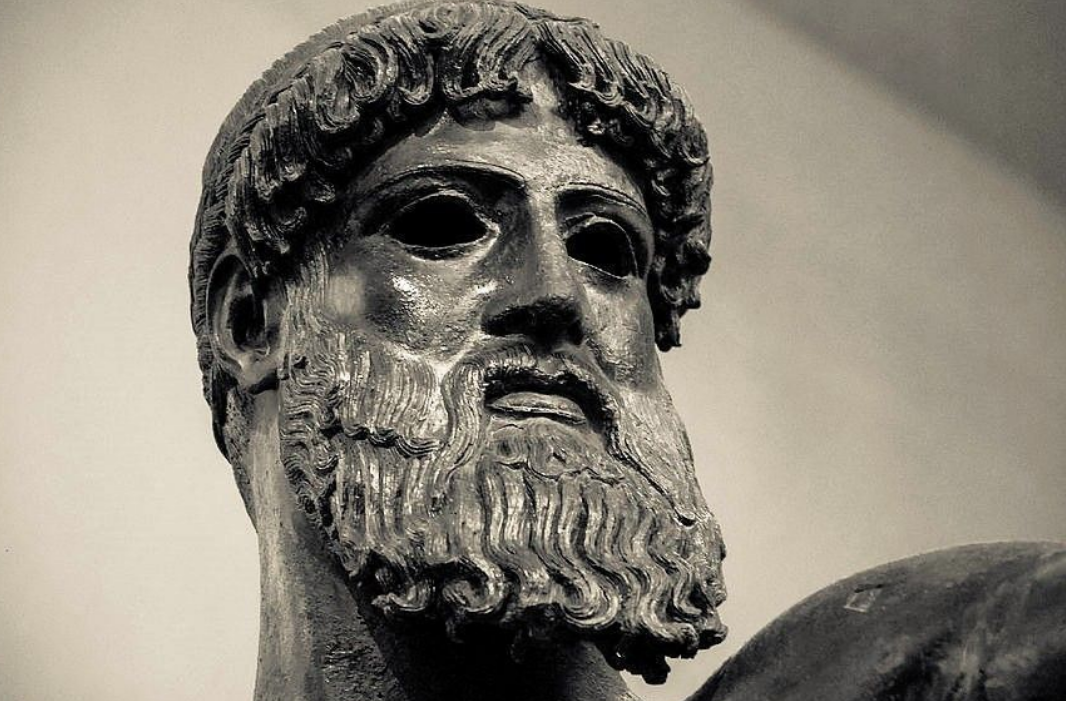

The bronze work is about 6 feet and 6 inches (2.09 m) high, and the figure is depicted in motion. He appears to be throwing a projectile, his arms outspread to a span of about 6 feet (2 m). It is believed that the piece represents an Olympian god. This is because it is highly realistic but is also idealized, with perfect proportions and a highly muscular frame.

The figure stands with his weight on his right foot and the other is slightly lifted off the ground. The head of the piece is very detailed, and the hair and the beard are very intricate. The eyebrows are missing; it is believed they were made either of gold or silver. His mouth was possibly once covered in copper. The eyes of the sculpture are now empty, and they may have once been filled with precious stones or even jewels.

Zeus or Poseidon

The identity of the bronze deity has been a source of debate ever since it was discovered. The pose of the figure suggests that it is throwing a projectile, which was never found. Some believe that the projectile was a thunderbolt. This would indicate that the figure was intended to represent Zeus, the King of the Olympians. In Greek mythology, he is often shown hurling thunderbolts.

Another view is that the figure is throwing a trident and this would indicate that the bronze actually depicts the god of the sea, Poseidon. However, there are several similarities between the representation and iconography of Zeus on pottery and coins. As a result, most experts believe that the Artemision Bronze is a depiction of Zeus.

Conclusion

The discovery of the Artemision Bronze in the waters of Euboea was remarkable. It encouraged the exploration of other shipwrecks in the Mediterranean and indirectly contributed to the development of marine archaeology. The masterpiece also allowed scholars to better understand the evolution of Greek art. If you want to see the Bronze in person, it is on permanent display in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, Greece, where it is one of the most popular exhibits.

References:

Moon, Warren G (1983). Ancient Greek Art and Iconography. Madison: Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.

By Jocelyn Hitchcock, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

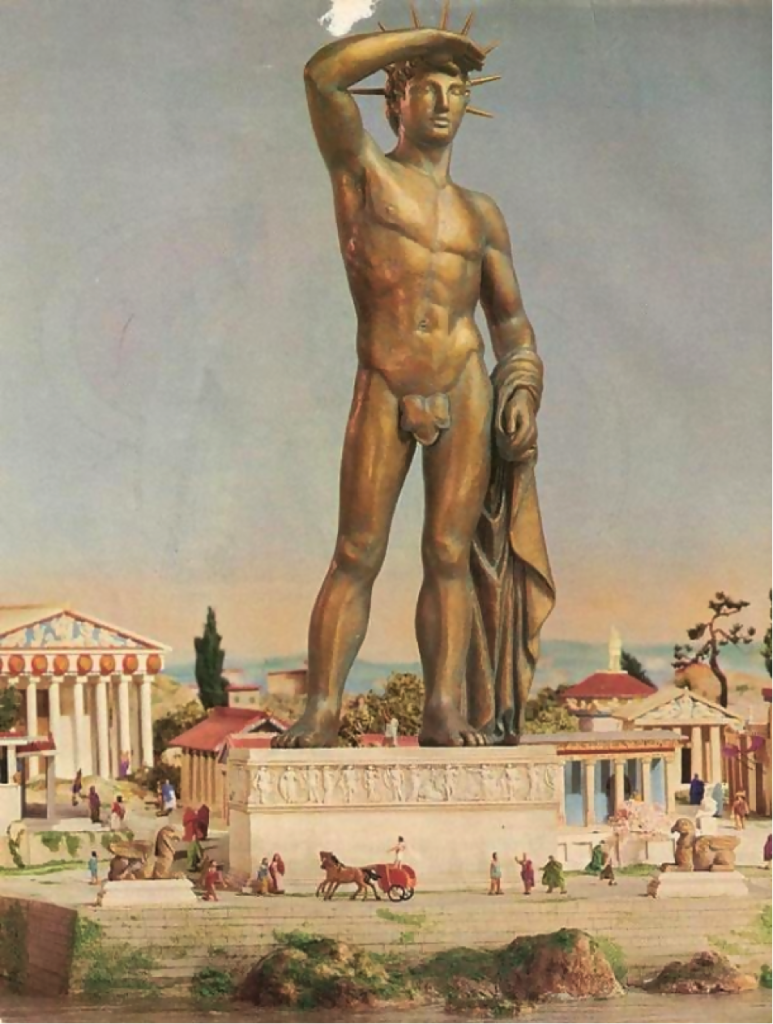

Considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the Colossus of Rhodes was a feat of ingenuity and engineering and served as a Rhodian symbol of victory.

The Colossus of Rhodes was erected in 280 BCE but was toppled by an earthquake in 226 BCE. The monumental statue remained fallen until 654 CE, before it was ultimately victim to destruction, fragmentation, and looting… and now, there is a chance it may be resurrected once more.

The Colossus of Rhodes: A Victory Statue

Located off the modern day coast of southwestern Turkey in the Dodecanese islands, Rhodes has been a major commercial hub throughout its history. The Hellenistic Period on Rhodes, when the Colossus of Rhodes was built, witnessed a flourishing of its economy and maritime interactions. Philosophy, science, literature, and art all found homes in Rhodes.

Then, in 305 BCE Antigonus I Monophthalmus dedicated to attack. In a power struggle over who should get to rule Rhodes after Alexander’s death, Antigonus sent his son Demetrius to capture Rhodes and secure it against the opposing Ptolemy and Seleucus factions. The capital of Rhodes was fortunately protected by a wall and required Demetrius to construct two separate siege towers to overcome it. Ultimately, both sieges were unsuccessful and a fleet from Egypt arrived to help defend Rhodes from Demetrius.

The conflict ended with a peace treaty and the people of Rhodes viewed it as a personal victory.

The Colossus of Rhodes

To commemorate their successful stronghold against Demetrius, Rhodes decided to erect a statue in honor of their patron god, Helios. According to Pliny, the Colossus took 12 years to build and was started in 292 BCE. Sculptor Charles of Lyndus was the artist behind the statue, but legend holds that he didn’t live to see its completion.

Construction of the Colossus of Rhodes

The Colossus of Rhodes was said to be 105 feet tall, made of Bronze paneling, and internally supported by columns and iron. Construction of such a statue was of course a feat in itself and several theories have been presented as to how such a work was completed. Scaffolding and earthen ramps have been used to complete the Colossus, but it is pure speculation.

Some scholars, both ancient and modern, postulate that the statue was cast in situ. They suggest that an earthen mound was built up around it as the workers went in order to reach the height of the Colossus as it is described by Philo of Byzantium.

An oil painting representing the ancient city of Rhodes by Frantisek Kupka (1906 CE).

Additionally, the positioning of the statue itself is unclear. We like to imagine that the Colossus straddled the harbor entrance, acting as a guard and port of welcome to visitors, inciting both respect and a bit of fear. However, this is not certain.

The Fall of The Colossus of Rhodes

As impressive as the statue was sure to have been, it only stood for around 54 years. In 226 BCE an earthquake rocked the region and the statue toppled to the ground. Strabo saw the fallen statue in his travels and wrote that, “he broke down by the falling from the knees,” and noted the Rhodian people did not restore it because an oracle instructed them not to do so. The colossus remained in this downtrodden position for nearly 800 years, when, according to Theophanes the Confessor, the statue was melted down and sold for its metal parts to merchants.

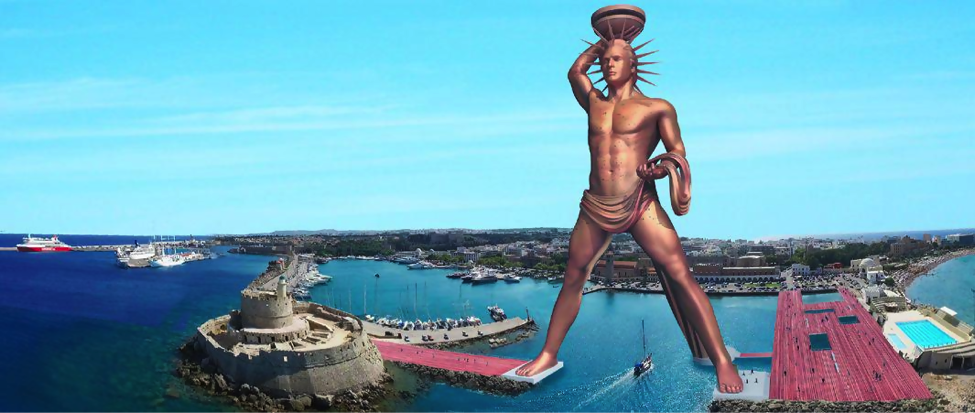

Potential construction for a replica

The Resurrection of the Colossus of Rhodes?

In the last few decades there has been a debate on whether or not to rebuild the Colossus of Rhodes. The project’s proposal states that the rebuilding of the Colossus would, “draw the attention of all humanity to our island [Rhodes], not purely motivated by a feeling of irredentism, but by creating a memorable cultural contribution of Rhodes.” The 2015 collective of architects, archaeologists, and civil engineers proposed to reconstruct a statue that would not only be much larger than the original, but would serve as a cultural center and lighthouse.

While we don’t know if this will happen or not, it would definitely be an astonishing feat… and a fantastic opportunity to see one of the seven wonders of world come to life again.