Philosophy: Who Needs It?

Written by Emma Coffinet, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

From the meaning of life to the art of politics and the nature of friendship itself, the iconic Greek philosopher Aristotle imparted much wisdom. So much of the great man’s work, penned over two thousand years ago, remains relevant, interesting, and inspiring to this day.

Countless texts and articles have been written on Aristotle’s views and ideas across all kinds of subjects. His influence has spread throughout the ages, even penetrating multiple religious bodies of thought in the process.

Indeed, Judaism, Islam, and Christianity all took influence from the man known to many as ‘The Philosopher’, and some of his most intriguing comments concern the subject of the soul, a concept that has been envisioned and interpreted in countless ways over the years.

Here we break down Aristotle’s view of the soul and his breakdown of it in three distinct ‘psyches.’

An Etymological Introduction

In order to fully understand Aristotle’s views of the soul, we must first pay close attention to the words he chose to use and how we interpret those words. The Latin title of his famous treatise On the Soul is De Anima, but the original Greek title is Peri Psyches.

Aristotle, however, has a very specific definition in mind when he makes use of the word ‘psyche’ or ‘soul’. He argues that there are three types of substance: matter, form, and the compound of both matter and form.

On the Soul focuses on living beings, such as plants and animals. In Aristotle’s view, living beings have souls and these souls are what makes them alive. For Aristotle, the soul or psyche can be classified as ‘form’. It is a living entity, that which essentially makes it a living thing.

The Three Psyches

For Aristotle, a soul is not an interior, ghostly agent acting in a body. It is an integral part of every living entity, and such an entity may be a plant, an animal, or a human. This is where Aristotle’s ‘hierarchy’ or categorization of the psyches comes into play. He postulated that there were three main types of psyche:

We can look at these three forms in a different way:

Essentially, the simplest way to look at Aristotle’s so-called soul psyches is to think of them in the form of a hierarchy of living beings, ordered by cognitive abilities, with humans at the top, animals beneath them, and plants at the base.

In Aristotle’s view, all of these different living beings have souls or psyches, which make them alive and drive them to remain alive by nourishing themselves, reproducing, moving, and so on, but these souls can come in different tiers, or levels.

The more advanced souls, found in humans, are capable of more functions and processes than those found in animals and plants, while those of animals are more capable than those found in plants. The rational soul is the highest form, followed by the Sensitive soul and then the Nutritive soul.

It’s also interesting to note that, unlike many of his contemporaries and other philosophers throughout history, Aristotle felt that the soul cannot exist independently of the body. He argued that it is not a body in and of itself, but rather that it ‘belongs to a body’ and must therefore always be present in that body. Should the body cease to exist, the soul goes with it.

Aristotle’s interpretation of the soul makes for fascinating reading and his treatise continues to be read and closely studied by scholars and students the world over. The soul may forever remain something of a mystery, but it’s clear that the great philosopher had a clear view of what it was to him.

Author’s Bio:

Emma Coffinet is a content creator for a range of sites and blogs, responsible for writing articles, social media content, white papers, essay paper examples, and contributes to the platform “write my thesis”. She likes to share the benefits of her experience with others by offering assignment help to students.

Written by Justin Osborne, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Whenever you surf the Internet, you‘re likely to bump into chatbots powered by artificial intelligence (AI). They serve all sorts of purposes: to provide website guidance, pinpoint products, answer your questions, and much more.

Chatbots are reportedly capable of answering 80% of standard questions. Research shows that nearly 70% of consumers prefer to use chatbots because they allow them to communicate quickly with a brand or company. Finally, 90% of companies report faster complaint resolution with chatbots.

But did you know that we probably wouldn’t even have chatbots were it not for Aristotle?

That’s right: modern technology owes a lot to the ancient rules of logic. Here’s why…

What’s A Chatbot?

Before we delve deeper into the topic, we need to explain what a chatbot is. By definition, a chatbot is a computer program that simulates human conversation through voice commands or text chats, or both.

There are several types of chatbots in use today, but it is the most complex one – AI-driven chatbots – which owe a large debt to the ancients. AI-driven chatbots use multiple techniques to analyze and resolve user inquiries using language processing, rules and machine learning, As such, they are able to contextualize conversations and identify customers’ specific needs and interests.

Their functionality is based on a few key principles of Aristotelian logic more than 20 centuries old. What are these key principles? Keep reading to learn more about it!

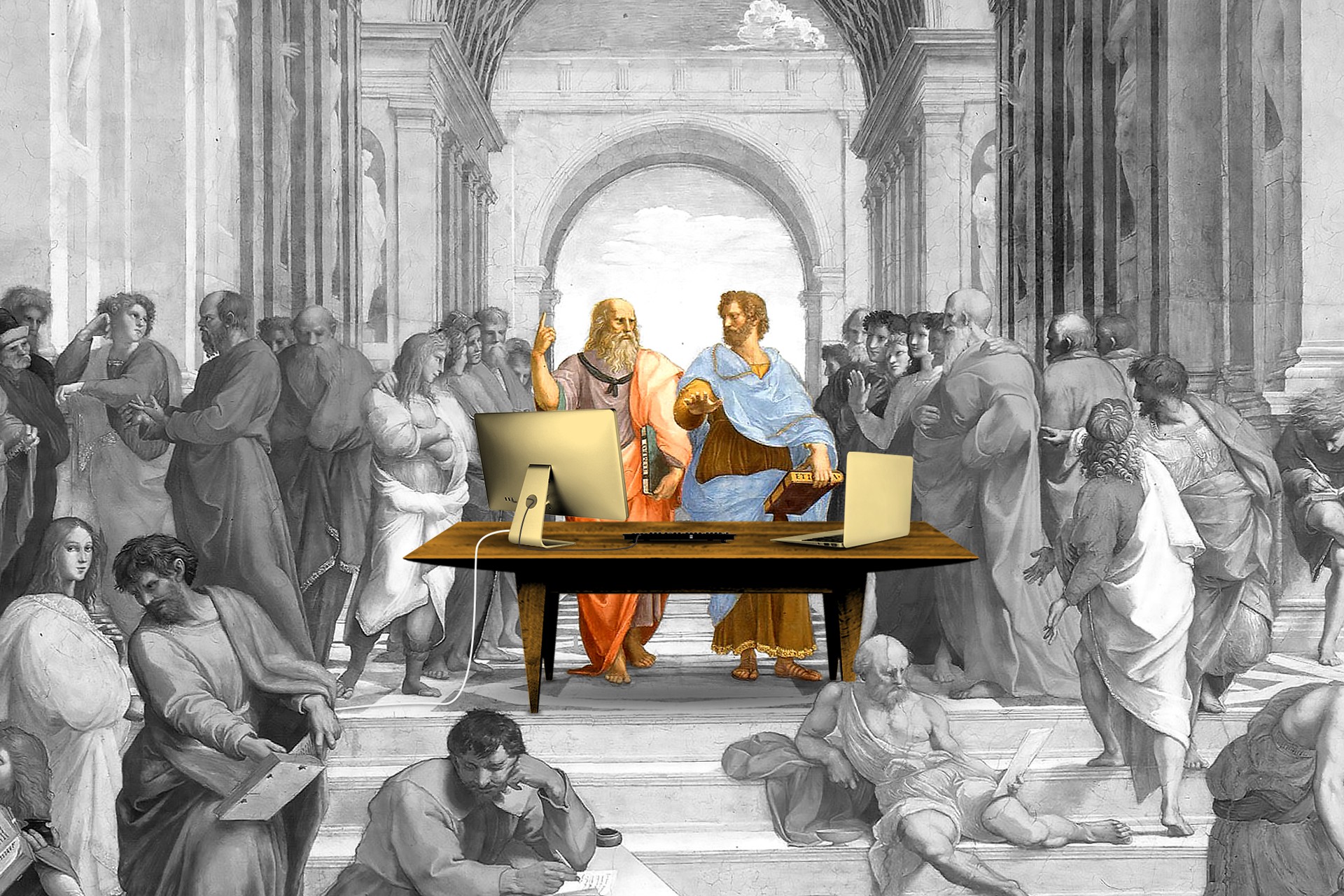

Roman copy in marble of a Greek bronze bust of Aristotle by Lysippos, c. 330 BC, with modern alabaster mantle

How Formal Logic Powers AI-Based Chatbots

Aristotle was the first to formally identify and organize the rules of logic in the fourth century BC. In his pivotal work, Organon, Aristotle says a conclusion can be derived from a group of mutually corresponding premises.

Called a syllogism, this represents a logical argument based on deduction. The other two forms of formal logic are induction and abduction. All three types are in contrast with purely mathematical principles of logic.

The reason for this is simple – purely mathematical logic rarely ever applies to human interactions, so it’s better to use principles that reflect everyday conversations between people. These principles – taken from Aristotle – developed into term logic, a system that takes into account the context of the conversation and adjusts to a given communication pattern.

The fundamental assumption behind term logic theory is that we use words to make a point — in term logic this is called a “proposition” — which, in turn, be considered true or false. The system works to discern the veracity of simple statements based on various factors.

For example, formal logic could claim something like this:

The example is very simple, but it shows how formal logic can sometimes mislead chatbots. In term logic, such inconsistencies are less likely because both fallible and infallible reasoning are taken into account when a statement is evaluated.

Such a system can perform all three types of conclusion-making processes: deduction, induction, and abduction. But once the first step is done, an AI-powered chatbot has to evaluate the truth value of each statement in order to identify which answer is best-suited to a given conversation.

The latest AI-based platforms react like human beings because of how they assess and respond when communicating. The response they judge the most natural and logical (via algorithms, of course) then becomes the answer to the user’s inquiry.

Bearing in mind that chatbots contain massive data libraries, it is clear that the system can almost instantly process and analyze millions of different terms and factor them into an ongoing conversation. As the result, chatbots can quickly come up with an answer that seems to be most logical in a given situation.

The Bottom Line

Chatbots have taken the online world by storm in the last few years, but it turns out that their roots go back all the way to Ancient Greece and Aristotle. In this article, we explained how Aristotle’s rules of logic make AI more human.

Have you ever talked with a chatbot? Did you like the answers? Tell us about your experiences in the comments below!

Justin is a blogger from Leicester, England, UK. He enjoys sharing his thoughts and opinions about education, writing for academic writing help and scholarship essay writing service.

It’s time to take a philosophical deep dive…

We all know Aristotle is one of the great pillars of ancient philosophy… we also know that’s he’s not particularly easy to read.

Nonetheless, his Politics stands as one the seminal works on the topic… but two and half thousands years later, we have to ask:

Is Aristotle relevant to modern democracy? Is it time for a revival of Aristotle’s Political philosophy and theory?

Bronze statue, University of Freiburg, Germany, 1915

This is what Adriel M. Trott, Chair and Associate Professor in Philosophy at Wabash College, Indiana and one of our Classical Wisdom Symposium speakers, has set out to prove.

While the history of political philosophy is a series of configurations of nature and reason, Aristotle’s conceptualization of nature is unique because it is not opposed to or subordinated to reason.

Adriel M. Trott, who focuses on ancient, continental and political philosophy, uses Aristotle’s definition of nature as an internal source of movement to argue that he viewed community as something that arises from the activity that forms it rather than being a form imposed on individuals.

Using these definitions, Trott develops readings of Aristotle’s four arguments for the naturalness of the polis, interprets deliberation and the constitution in Politics as the form and final causes of the polis, and reconsiders Aristotle’s treatment of slaves and women.

And she does this all to show that Aristotle is relevant for contemporary efforts to improve and encourage genuine democratic practices.

Something, I think we can all agree, is a very important topic at this time.

You can discover for yourself Adriel’s insights and Aristotle’s relevancy in her latest book: Aristotle on the Nature of Community.

Described as, “a fresh, substantial, and engaging contribution to the ongoing Aristotle revival in political philosophy and theory” by Stephen Salkever, Journal of the History of Philosophy – Aristotle on the Nature of Community is a thoughtful and provocative re-reading of Aristotle.

You can get your Own Copy Here.

But wait! There’s More! Adriel M. Trott has written extensively on Aristotle…

In her first book, Aristotle on the Matter of Form: A Feminist Metaphysics of Generation, Adriel M. Trott allows us to think anew with Aristotle… not just about form and matter, but also body and soul, male and female, and much else. Informed by and responding to feminist engagements with these issues, Trott challenges binary models of these couplets, often attributed to Aristotle, to show us innovative possibilities for thinking how we come to be and what we might become.

All Classical Wisdom Symposium Attendees will get an additional 30% OFF “Aristotle on the Matter of Form”

You can also catch Adriel M. Trott LIVE at the Inaugural Classical Wisdom Symposium… Make sure to check out all the details below!

(You may have noticed that the option to buy the Wine Included ticket has now closed… but don’t worry! You can still enjoy the full two day conference, watch the presentations and panel discussions with our One Day or Two Day pass.)

Written by Visnja Bojovic, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

In a previous article, we discussed Aristotle’s inspiration to write the Poetics (a treatise on drama and literary theory), and the notion of catharsis that emerged as a result. As we concluded, it is highly probable that Aristotle’s treatise was written in response to Plato’s criticism of poetry.

Plato objected that poetry plays on the emotions and thus undermines the highest part of our soul, the part that should at all times be in control—Reason. Aristotle cunningly showed, using the notion of catharsis, that while poetry does indeed play on the emotions, it does so in a way that enhances our reasoning!

Along with catharsis, Aristotle developed another very important concept that uses Plato’s arguments against him. This concept is related to the intellectual side of Plato’s arguments.

We are all more or less familiar with Plato’s allegory of the cave. Roughly put, the main message is that the world detected by our senses is a “shadow”, a mere copy of an immaterial world of eternal Forms that are incomprehensible to us. This world of Forms consists of abstract, perfect, unchanging concepts or ideals that transcend time and space, and which constitute the true nature of reality. Therefore, what is accessible to human beings is merely a misrepresentation of reality, a mimesis (μίμησις) of these pure Forms.

Illustration of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave (Source).

Now, if the world we encounter through our senses is already merely a copy or imitation of reality, then anything that imitates this imitation would be even farther removed from the truth! Poetry is one such imitation of an imitation. Because it imitates and relies on the world of the senses for its material, it takes us even further away from the truth, and thus nothing good can come from it.

“…I said that poetry, and in general the mimetic art, produces a product that is far removed from truth in the accomplishment of its task, and associates with the part in us that is remote from intelligence, and is its companion and friend for no sound and true purpose.” “By all means,” said he. “Mimetic art, then, is an inferior thing cohabiting with an inferior and engendering inferior offspring.” (Plat, Rep, 10.603 a-b)

Diplomatic as always, Aristotle accepted part of Plato’s theory, agreeing that art is a form of imitation. He even accepted Plato’s division of storytelling according to the different types of mimesis employed in it. Yet he did not agree that mimesis is bad in and of itself—quite the opposite! Aristotle argued that imitation is completely natural for human beings, and a necessary way of learning:

From childhood a man has an instinct for representation, and in this respect, differs from the other animals that he is far more imitative and learns his first lessons by representing things. And then there is the enjoyment people always get from representations. What happens in actual experience proves this, for we enjoy looking at accurate likenesses of things which are themselves painful to see, obscene beasts, for instance, and corpses. The reason is this: Learning things gives great pleasure not only to philosophers but also in the same way to all other men, though they share this pleasure only to a small degree. The reason why we enjoy seeing likenesses is that, as we look, we learn and infer what each is, for instance, “that is so and so.”

Fig. 7 Wallerant Vaillant, after Raphael, Plato and Aristotle, 1658–77, mezzotint Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. RP-P-1910-6901 (artwork in the public domain)

Thus, for Aristotle, imitation is inherent in human nature and plays an essential role in the formation of knowledge. Mimesis represents the crucial link between pleasure and learning because the audience enjoys learning while watching the results of mimesis. The thing represented to us through mimesis helps us learn and makes it enjoyable. Mimesis does not, as Plato thought, take away from knowledge and the search for truth.

Aristotle’s Poetics, small though it is, managed to shape literary theory for centuries and continues to do so. Today, we are all Aristotelians when it comes to art. I know I’m not the only one who has left a movie theatre feeling as though I’ve learned a valuable lesson, or who has watched a tv show and related some part of it to a struggle in my own life. In short, anyone who believes that lessons about life can be learned through epics, tragedies, and comedies alike is an Aristotelian when it comes to art.

Aristotle had a knack for turning the teachings of his mentor against him. We now see that he did this with catharsis and with mimesis. Judging from the fact that Aristotle’s arguments in the Poetics prevailed over Plato’s criticism of poetry, are we to think that Aristotle does indeed have the better argument? Living in an era where emotion seems to reign over reason, should we be more open to sharing Plato’s concerns about poetry and other arts that play on our emotions?

Does it lead us out of the cave and into the light, or is it just one of the many chains that shackle us to the cave wall, leaving us only with shadows?

The verdict? I leave that to you to decide, dear reader.