Written by Danielle Alexander, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

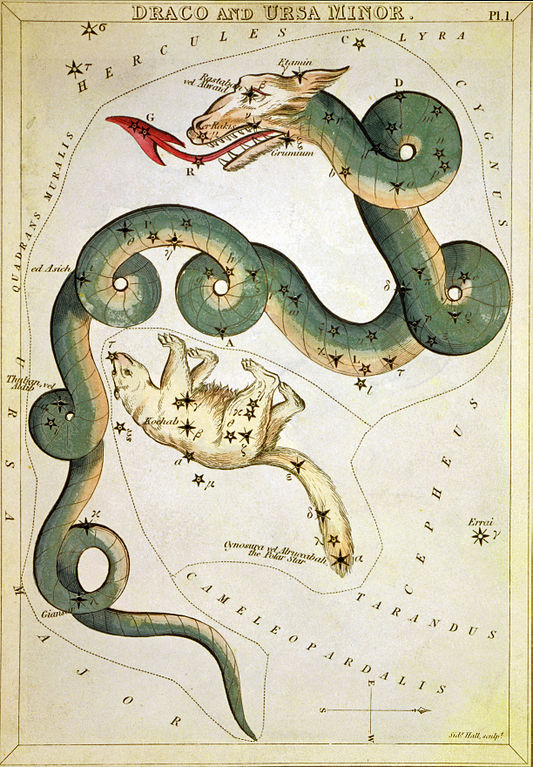

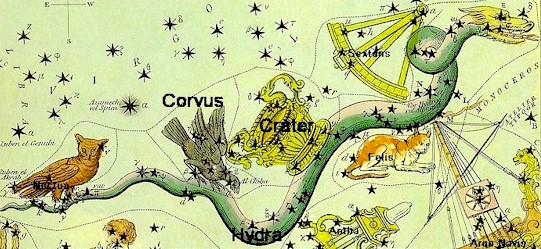

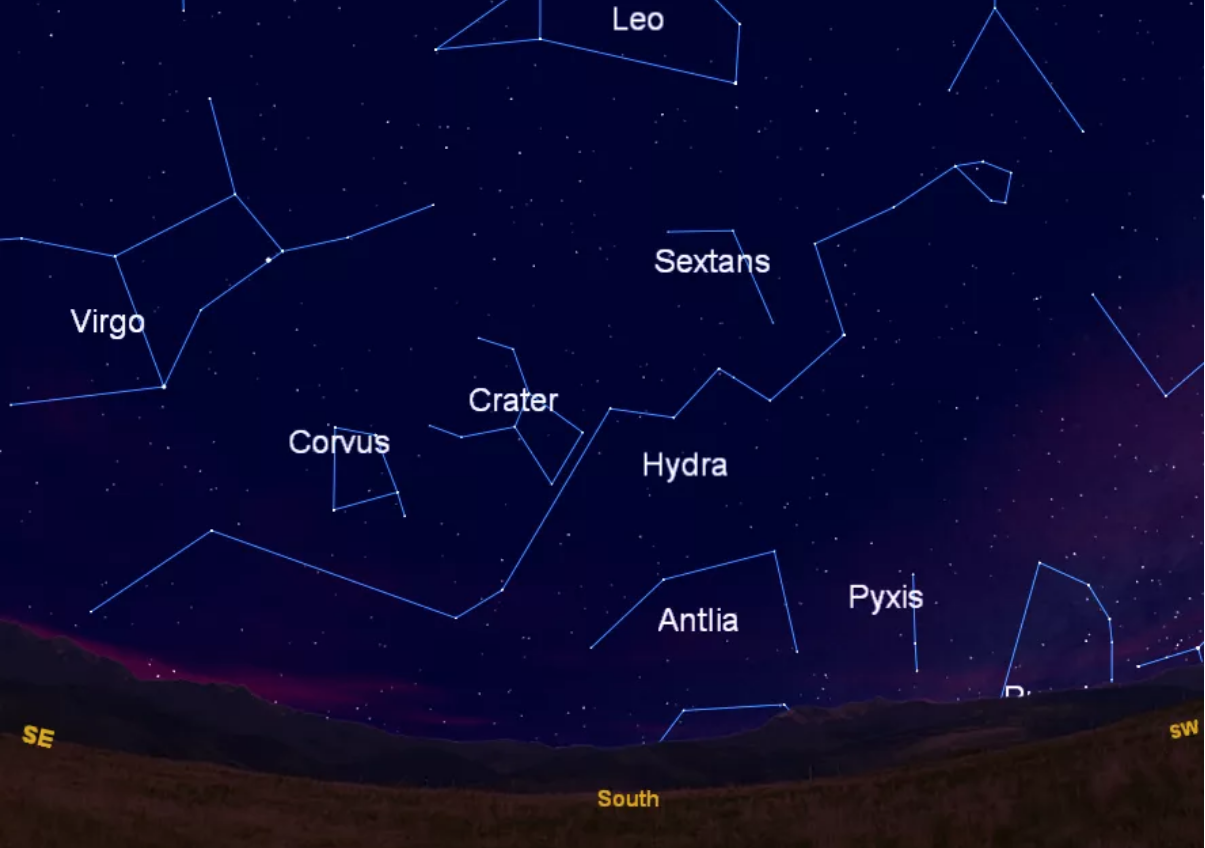

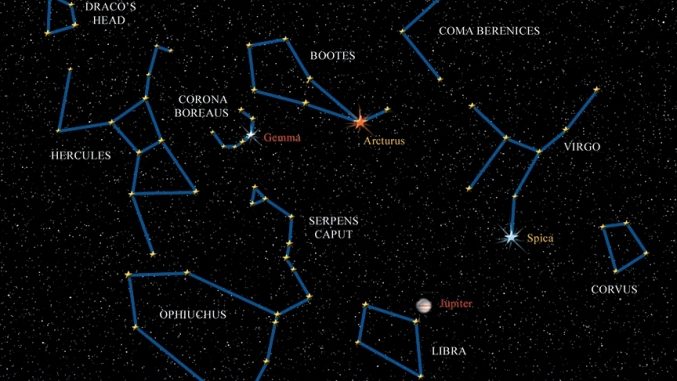

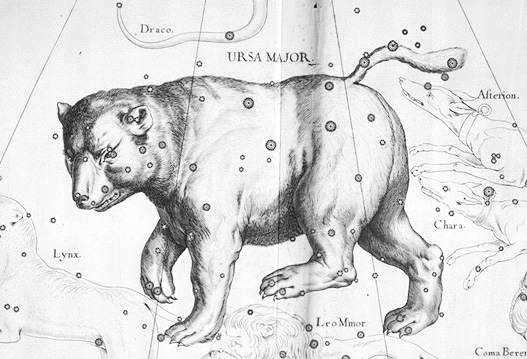

There are certain mythical creatures that seem to exist in most cultures, and the dragon is one of them. The Greeks were no different and immortalized a serpentine shape in their sky situated between the two Bears (Ursa Major and Ursa Minor).

Dragon to Snake: What happened to the wings?

In India, this star cluster is referred to as a crocodile or alligator, but in other regions, it has been identified as a Hippopotamus. In the classical world, this curling constellation is known as the serpentine Draco.

The Mesopotamians originally identified wings with the constellation, however, the Greek philosopher Thales (c.6th century BC) lopped them off to form Ursa Minor. One of its tail stars, Thuban, was the Pole Star around 2,800 BC, but is not now due to the precession of the equinoxes.

Greek astronomy

The earliest surviving written Greek sources are the war-filled epics of Homer and cosmological fables of Hesiod (both dated roughly to the 8th century BC). The philosopher Plato encouraged the introduction of astronomy and astrology from the East and Egypt, holding sky-watchers in high regard.

He also believed the Greeks would improve upon the imperfect, inherently unreliable Eastern system by employing geometry and mathematics. By c.400 BC, the Babylonian zodiac, which had emerged c.1300-1100 B.C, made its way to Greek shores.

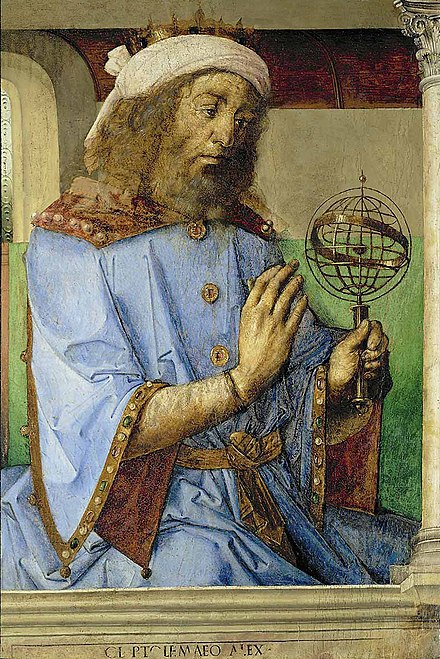

Ptolemy’s The Algamest (A.D 150), describes traditions that had been popularized in Greek society by way of a popular poem by Aratus c. 275 B.C, The Phaenomena. This poem was said to heavily reference the works of Eudocus (366 B.C), lost tomes that are said to contain the earliest description of Greek skies.

During the 2nd century BC, Hipparchus wrote The Commentary and it marked a shift in how constellations were understood by introducing a scientific mode of enquiry.

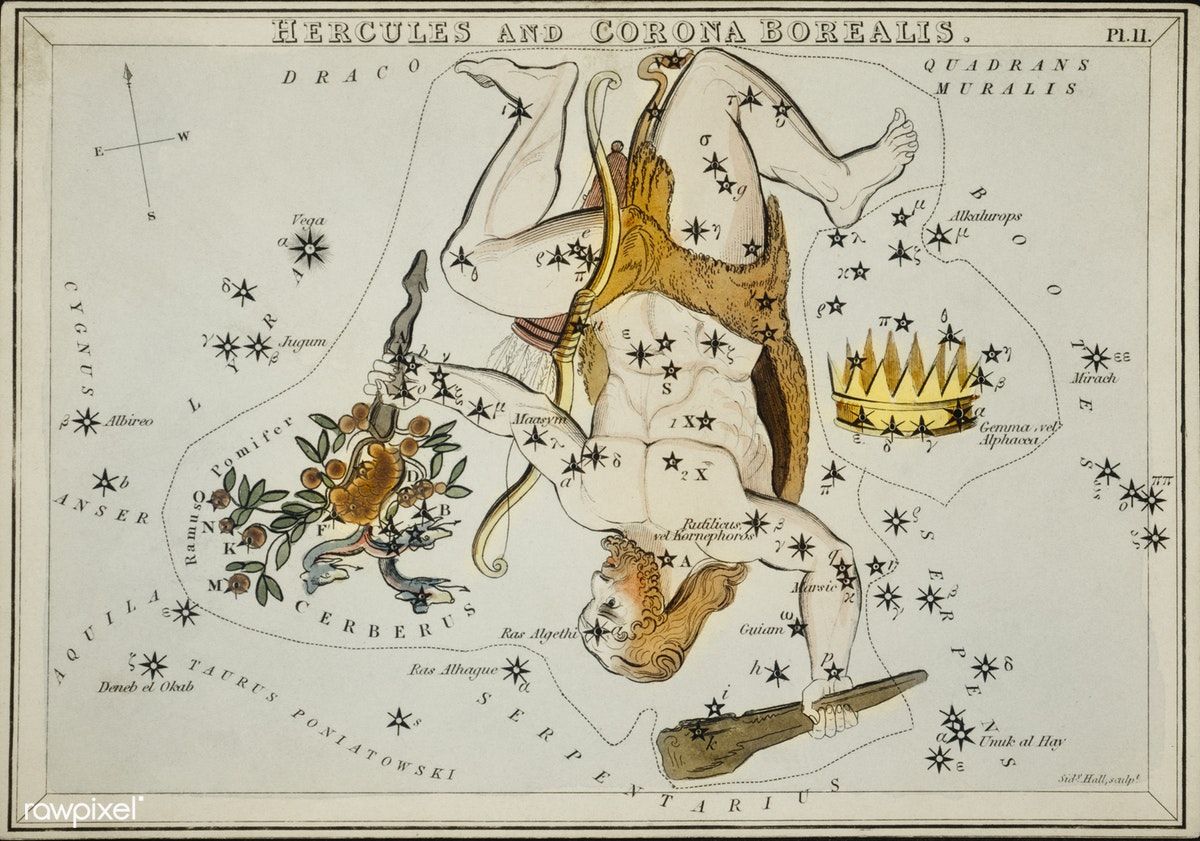

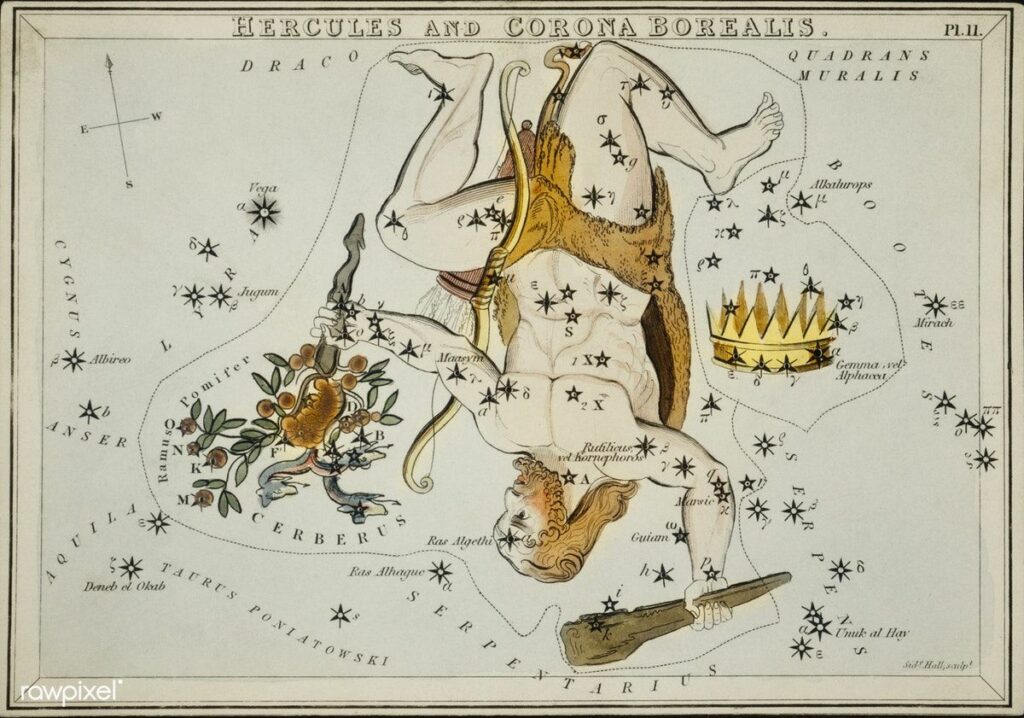

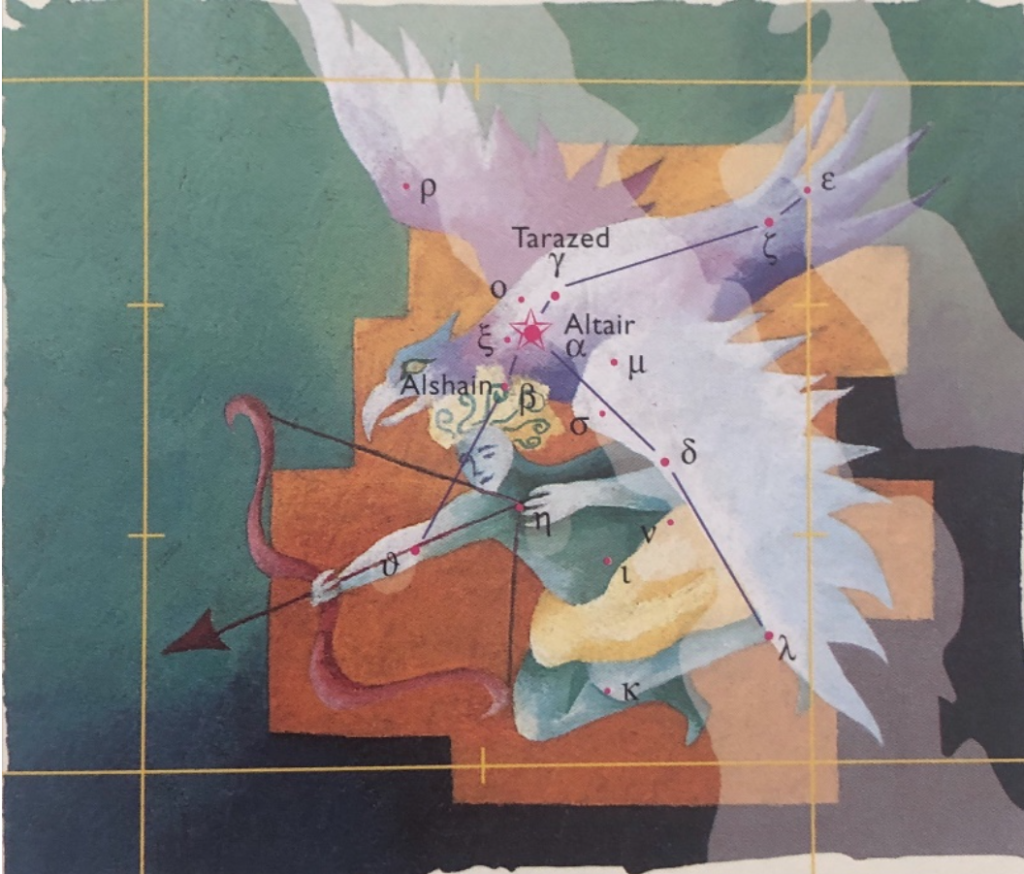

The Greek system of constellations housed only 18 star clusters that did not originate elsewhere. These are undeniably Greek, representing heroes such as Heracles and Orphicous and cultural familiarities, such as the Dolphin.

The Greeks’ relatively late entry into the constellation conversation did not stop them from introducing the term ‘katasterismos’ or catasterism, which means the process of being set in the heavens.

They were also not afraid to rename the star-images, denoting one the ‘Triangle’ during the 6-4th centuries B.C, corresponding with the introduction of organized geometry. This reveals how changes in society are reflected in the heavens. As the Hermetics’s would say: As above, so below.

Ssssnake: Protector or Problem?

There are several variations on how a serpent came to be coiled amongst the stars.

Some accounts say the snake is the memory of the magnificent Python of Delphi, slaughtered by Apollo when the god came to claim the impressive oracular site as his own.

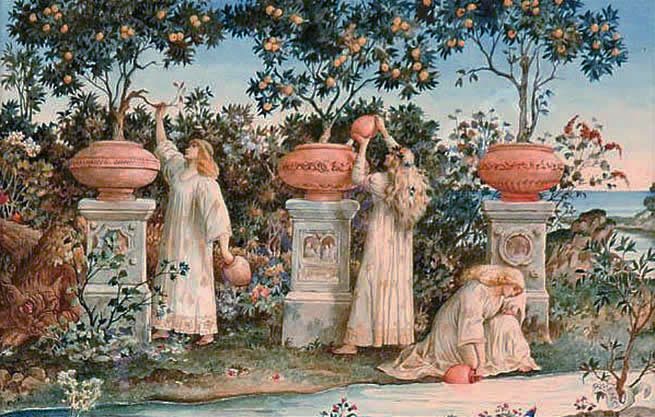

Other stories speak of it as a loyal serpentine guard of Hera, who catasterised (set in the heavens) the snake, in appreciation for its service. During the incestuous wedding festivities of Hera and Zeus, the bride received a glorious gift from Gaia and the Horai (Earth and the Seasons) — a branch laden with golden apples. Hera, admiring their beauty, begged Gaia to house them in her glorious garden.

This garden lay by the feet of Atlas and his cheeky daughters, the Hesperides, who were frequent thieves of its fruits. Thus, Hera appointed Ladon the serpent to guard her precious gift. One cannot help but wonder if these golden apples were those involved in the Epic Cycle, the famous saga in Homer’s Iliad.

But the story doesn’t end there. Unfortunately, Heracles visited the garden and shot the snake with an arrow, ridding the Eden of its protector so he could nab the apples. Alternatively, he slaughtered the snake during his trials. Either way, heartbroken, Hera placed the snake in the sky for eternity (this undoubtably was another justification for Hera’s vengeful persecution of Heracles).

Alternatively, the snake constellation has been tied to Zeus, hiding in dragon form from his father Cronos on the island of Crete. Interestingly, Crete is dominated by serpentine iconography, often associated with the ‘Great Mother Goddess’ and birds.

Grecian culture can be traced back through the Mycenaeans to the Minoans, as was recently demonstrated by genetic analysis. The Minoans in Crete were known to be a Bronze Age powerhouse and were likely the dominant stepping-stone for the introduction, and eventual domination (academically agreed to be c.2000 BC), of eastern Indo-European ideologies in Greece. They were no stranger to assimilating with indigenous communities, and the native cosmology helped form what today we know as the Greek Pantheon.

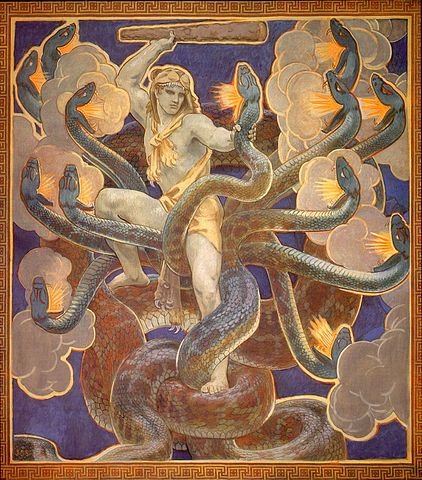

Other mythological tales of Draco see the coiled serpent as the only dragon who fought with the Titans against the Olympians in the Titanomachy. It is said that after ten years of conflict, Athena met with the dragon on the battlefield and proceeded to hurl it by the tail into the heavens, where its lanky body snagged on the North Pole and it swiftly froze.

The great war between the gods finished not long after, and the Olympians reigned supreme. It is interesting to note that Athena, connected with the owl and a masculine goddess, was the Olympian to throw the serpent to the sky. Could this be a mythical representation of the patriarchal Indo-Europeans, using mythological assimilation to make the process easier? By the Gigantomachy, Athena, clad with adopted serpentine imagery, led battles against the Giants, described as wild and snake-like.

Also concerned with dragon, rather than snake form, this constellation potentially depicts the dragon that had guarded the spring of Ares until Cadmus came along.

Cadmus killed the beast and sowed its teeth into ground. Surprisingly, they sprouted into men, known as the Sparti, who promptly fought to the death. Only five survived, and these are the ancestors of the five noble families of Thebes. This appears to be a localized version of the tale, concerned with the birth of a city state. Mythical political propaganda is not uncommon in the ancient world due to the social status that came with having heroic ancestors. Such claims gave them foundations in antiquity, in a Golden Age long ago that the Greeks aspired to achieve again.

Serpents were frequent protectors in ab aeterno mythology, representative of an older age. It is said that even the Acropolis of Athens was guarded by a snake, Erichthonis, who loyally protected Athena when coiled in her shield. In older mythos, snakes were concerned with goddesses and represented life, death, and rebirth.

References:

Cornelius, G. (2005). The complete guide to the constellations. London: Duncan Baird, pp.76-77

Schaefer, B. (2006). The Origin of the Greek Constellations. Scientific American, 295(5), pp.96-101.

Kirk, G. S. (1972). Greek Mythology: Some New Perspectives. The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 92, pp.74-85

Ératosthène, Hygin, Aratus and Hard, R. (2015). Constellation myths. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.12-14

Graves, R. (2012). The Greek myths. New York: Penguin Books.

Douglas, H. (2020). When is a snake just a snake? The lack of cultic continuity between the Minoan Mother Goddess and Classical Greek deities based on snake imagery. Unpublished thesis. University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Wales.

Ribbens Dexter, M. (2011) The Monstrous Goddess: The Degeneration of Ancient Bird and Snake Goddesses into Historic Age Witches and Monsters. Journal of Archaeomythology, 7:181-202. ISSN 2162-6871