Old Ideas Renewed: Science, Philosophy, and Perception as Illusion

Written by Justin D. Lyons, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The philosopher in Plato’s Laws, called the Athenian stranger, converses with old men settled in their habits and attached to the regimes in which they live. Kleinias and Megillus are exemplars of pious traditionalism. Moreover, they propose to travel to its very source–the cave in which the god delivered the laws of Crete. Two topics one never discusses must be confronted: politics and religion.

Such challenges are usually not well received and can result in ingesting harmful substances.

Because of the subtlety required in questioning the firmly-held beliefs of his interlocutors, we can expect the Athenian to frame his speech very carefully.

The journey will be difficult for them–physically, because they are old; mentally, because they must question what they are not accustomed to questioning; and spiritually, because they must summon the courage for that questioning.

The travelers will rest from time to time in the shade of trees, for the bright light of inquiry constantly peering into the dark places of convention and accepted belief can be overwhelming. They must also be encouraged to continue their wearisome journey; the Athenian rallies them to the cause and keeps them moving forward.

He begins with an inquiry into the incompleteness of the Dorian regimes, which were ordered exclusively to martial virtue. He attempts to guide his interlocutors to the understanding that laws should aim at the whole of virtue. This process involves delicate questioning and the use of various images to lead them beyond strict conformance to the conventions of their own regimes.

That the actual practice of politics is at stake is made clear when Kleinias reveals that he is about to engage in the task of founding a city.

Colossal statue of Zeus in the ancient Greek city of Lebadeia (modern Livadeia), by Joseph Gandy, 1819, source: Tate Britain

The Athenian then takes them through the creation of a city in speech, which emphasizes the massive difficulties involved in founding and maintaining a virtuous city and thus makes clear the necessity of philosophical wisdom.

The philosopher educates men who will have political power, but shows a reluctance to become involved politically himself. The Athenian evades one attempt to involve him in the new colony by suggesting that it is not his responsibility (Book VI).

But when the travelers reach the end of their journey, Kleinias and Megillus decide that the city they have been discussing simply cannot be founded without the presence of the Athenian:

Meg.

Dear Kleinias, from all that has now been said by us, either the city’s founding must be abandoned, or this stranger here must not be allowed to go, and by entreaties and every contrivance he must be made to share in the city’s founding.

Kl.

What you say is very true, Megillus, and I will do just these things, and you must help.

Meg.

I’ll help (Laws, 969c-d).

They have now reached the cave and will compel the Athenian to go in. Like the famous image in the Republic, this cave represents the realm of convention and obfuscation from which the philosopher has already escaped.

By now, Kleinias and Megillus have glimpsed the true nature of law and recognized extra-political standards of judgment. In fact, they have grasped the importance of philosophical understanding so well that they press the Athenian to get used to the dark.

The Athenian does not answer them. Apparently, he does not wish to go in. His silence is an indication that, while the philosopher’s wisdom is necessary to guide the city, he does not himself wish to engage in politics. His quest for wisdom requires that he maintain the freedom to pursue his inquiries without directly engaging in political rule.

The suggestion of compulsion in the remarks of Kleinias and Megillus indicates they are aware of the Athenian’s reluctance, though it can be doubted whether they understand it. They have grasped the importance of philosophy, but they have not grasped philosophy itself or come to appreciate its need for independence. They are concerned with the health of their city; thus, they remain willing and able to use compulsion, the means available to political men, to force wisdom to meet the practical needs of politics.

This outcome raises the question of how well the philosopher knows how to escape the snares of pious traditionalism. He knows well how keep political men talking, convincing them that philosophy is not useless to political life. But he does so by descending to the particulars of founding a city that will inevitably require a pious traditionalism of its own.

The philosopher seems to be caught in a dilemma: If he wins, he loses. The very nature of his investigations necessarily puts him in contact with purely political men. If he wins them over, they will force him to participate in practical politics. He will not have convinced them of the desirability of philosophical wisdom as such, but only of its usefulness, and in so doing will have destroyed the freedom necessary for pursuing the very wisdom he has employed.

Written by Visnja Bojovic, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

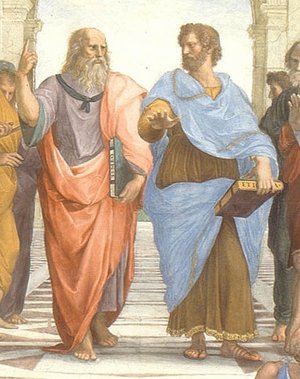

It is old news that ancient thinkers were constantly questioning human learning, morals and behavior. Greek perceptions of the mind or soul were very different from contemporary views, which can make them all the more difficult to grasp for the modern reader.

However, we will make an effort to understand quite a complex concept in the ancient Greek thought: mind. Considering that the mind is quite a broad topic, I decided to focus on what it meant to just one philosopher—Plato.

Starting as early as Homer, ancient thinkers began differentiating learning through perception or sensation from the learning that comes through awareness. Even though we can claim with certainty that this distinction existed, these two ways of learning were never clearly defined, and a lot of things about them remain obscure.

One thing we do know for sure is that learning through perception or sensation in Greek was called aisthesis (αἴσθησις) and that learning through awareness was always related with nous (νοῦς).

The meaning of nous depended on the concept it represented, as well as the philosopher who used it, but, roughly put, we can say that it meant ”mind”.

Aristotle claimed that the Presocractic philosophers did not make this distinction between learning through the mind and learning through perception. There were, however, some attempts.

Heraclitus, for example, in his teaching about logos, agrees that the senses are unreliable, but he does not clearly explain how logos (the truth, the essence) is revealed to us. He does relate it with nous, though.

Plato sheds new and slightly clearer light on the concept of learning through his theory of knowledge as presented in Phaedo. He puts the soul in the center of this theory, making all cognitive activity the result of the operation of the soul. He characterizes sensation as the perception of the soul through the body, whilst reasoning is made by the soul itself.

However, in Phaedo, this distinction comes through in terms of the objects perceived/understood. There is no further clarification regarding how these processes function nor the differences between them.

In the Republic, on the other hand, these concepts reappear in a much more complex manner through Plato’s famous analogy of the divided line (γραμμὴ δίχα τετμημένη). In a short discourse (509d-511c), Plato’s Socrates presents an epistemological theory that later proved fundamental to Plato’s metaphysics. In this discourse, he describes the four levels of existence and, more importantly, the four corresponding ways of knowing these levels of existence—i.e., the four ways of accessing knowledge.

Plato visualizes this as a line that is divided into two, unequal parts, which are then further divided into two parts each. These four parts represent four different states of mind, as well as four ways of acquiring knowledge. The fact that these parts are unequal is important.

The first part, the smaller one, consists of the visible world, the world we perceive through senses, or the physical world, if you will. This physical world is just a series of passing reflections of the other world, the world of ideas.

This corresponds with the lowest form of learning, called eikasia (εἰκασία) (opinion-imagination). In this realm, the eye makes guesses whilst observing the likenesses of the visible things. Another part of this world is pistis (πίστις) (opinion-belief), in which the eye makes predictions based upon observing physical, visible things.

For us, the second part is far more relevant and interesting, because in it, Socrates claims that the knowledge we have of the forms is of a much higher importance than the knowledge of the particulars of the perceptual world. He refers to this as dianoia (διάνοια), which Plato characterizes as knowledge (thought) that recognizes some ideas and makes hypotheses, similar to mathematical reasoning.

The highest realm and the highest form of knowledge is our noesis (νόησις). This is considered philosophical understanding, containing ideas and truth given by the Good itself.

It is not accidental that noesis is represented by the largest part of the line, given that Plato thought that few people understood the world of ideas. This is elaborated further in his allegory of the cave, which most readers are probably already acquainted with. Understanding noesis can make it much easier for us to understand Plato’s epistemological theory.

Through reading about this, we may (and probably will) agree with Socrates that we know that we know nothing, as the highest truth is quite difficult to grasp. However, learning about the questions that the ancient philosophers were discussing and grasping the concepts that they came up with will hopefully take us one step closer to understanding of noesis itself and the greater world in which we live.

References:

Phaedo, Plato

Republic, Plato

Greek Philosophical Terms, F. E. Peters

Psychology, Philosophy, and Plato’s Divided Line, John S. Uebersax

Written by Nickolas Pappas, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

There’s a story about love in Plato’s Symposium that captures the feeling of romantic love superbly, like a Valentine to everyone who’s ever had that experience. This may be why the story is one of those pieces from a Platonic dialogue (like the Atlantis legend) that people know about even if they don’t know it’s from Plato.

Within the Symposium the story is told by Aristophanes, in real life a comic playwright, in this dialogue also someone relaxing at a dinner party with Socrates and others and wondering where love comes from. He says the first human beings were double creatures: a big head on each one, with two faces looking in opposite directions, and a spherical, four-legged, four-armed body.

These first people were contented things but they thought they could conquer heaven, and to punish them for their arrogance the gods decided to weaken them. Zeus and Apollo cut every happy four-legged double-faced human into a pair of single-faced bipeds—needless to say, unhappy ones. Misery defines existence for people like them, which is to say people like us. You have had half of you amputated. You’re all phantom pain.

The story slides out of mythical past into the literal lives of those hearing it. You’re only half alive until you come upon that one that you used to be joined to. No wonder you embrace each other, trying to go back to your original condition.

Sex is part of that reunion. The gods planned it that way by moving the first split humans’ genitals around to their front sides, so people could stimulate each other as they hugged and find some relief. And yet, as Aristophanes tells the other guests at this dinner party, sex isn’t everything even in this earthy tale. These couples want something else when they find each other. They may not have the words for their yearning, but what they most crave (isn’t this romantic?) would be to find themselves reconnected into a single being.

There are other notable details in the story. It seems to acknowledge sexual orientation as few works did before the modern age. For this reason there’s a musical number based on the story in Hedwig and the Angry Inch. But even though Plato is unembarrassed by same-sex desire, the taxonomy of sexual identities is an addition to the story, whose main message is that love comes from a crisis long ago. You used to be half of a large complete person, and you never will be again.

Later in the Symposium Socrates offers an alternative theory about thoughtful lovers’ redirecting their erotic desire to worthier objects like social institutions, and then every species of learning, on up to the philosophical understanding of beauty itself.

But even without this theory, Plato’s readers have dashed cold water on the fantasy from Aristophanes. How would you ever find that Ms or Mr Right, if this were true? You don’t know what to look for. It’s impractical to try embracing everyone in the world to see if it will give both of you that special spark.

Let’s say you find someone special. You might reach for words that justify your love – witty, kind, sings like an angel – but according to this story, they’re excuses. The vital decision of whom to join with for life is a decision you made for no other reason than that this is your missing half. Maybe this explains why some long-time couples can only shrug and say they grew up together.

That seems to be the end of it: some recognition of romantic passion on one side, unsexy common sense as the alternative. The true romantic isn’t really silenced by these reasonable objections, because after all, everyone knows the right person is hard to find. (What else would it mean for there to be a right person?) You can still go on dreaming the dream of romance. There’s no law that says you have to be reasonable.

But Plato has more tricks up his sleeve than common sense. He’s more of an underminer than a naysayer. What if the danger with the story of Aristophanes were not that you never get together with the right person, but that you might?

Look at three details in the story that could seem extraneous. Imagine Plato putting Aristophanes on the couch in the psychoanalytic sense instead of the couches that the ancient Greeks reclined on to eat. As Aristophanes spelled out his myth, the double creature that was divided to create you and your special lover had two faces that looked very much alike.

When those first beings were cut in half, Apollo stitched them up leaving only one scar, the navel, and he turned their faces so that they would always look down at themselves and see this reminder of their old separation.

Turning their faces meant that they no longer saw their sex organs (this was prior to their movement, so they were on the other side), meaning these half-people pined for each other without hope for relief, and not knowing what to do together when they did meet up. So then the gods put them through a second operation, moving their genitals to the front side where people could see them. Romantic longing then acquired the new accompaniment of sexual intercourse.

If you were this storyteller’s shrink, you might circle back to some of these points. The story works fine without them, so what are they doing there? Romance is still romance, and the picture of someone you desire as someone you share a body with continues to be a compelling fantasy. “So why did you throw in the part about looking down at your belly button?”

Aristophanes shrugs it off. A fun detail. You tell a story like this and you throw in a little reality as if it’s supporting evidence. The gods cut you apart from your other half so they leave a scar. “It’s a joke!”

But the navel really is a scar, you point out, and it really does show where you were separated from someone else, namely your mother.

“I wasn’t thinking of that!”

“Wait a minute.” You’re not the type of therapist who interrupts, but you want to stay on track. “Why did you say the two faces were alike? People fall in love all the time with people who don’t look like them. But you know who does look alike? A mother and her child.”

Things never move this fast in real-life treatment. For dramatic purposes I’m having you resemble the type of analyst who shows up in movies with a gotcha question that rips away the veil of illusion. But then this Aristophanes is not a real-life character. Plato composed the story that Aristophanes told, making it up out of thin air or taking elements from someone else’s invention. He planted these clues in the story, hints that this is not really about a mythical past and other kinds of beings. If you try to tell a story about powerful one-on-one romantic feeling that goes beyond explanation, you will end up telling the story of returning to your mother.

Plato didn’t know the kinds of things that modern psychologists know. He had little idea of how the brain works. (He did know that thinking happens in the brain, and that a disease like epilepsy, despite being called “sacred,” had its origin in the brain’s material physiology.) But he had made close studies of the people around him, and he observed the characteristics of those who struck him as unbalanced – the form that inner conflict took in such people, or the socially unacceptable sexual desires that lurked in people’s souls and often appeared in their dreams. He had the delicacy to pick up on the resemblance between unquestioning erotic love in adulthood and the infant’s unquestioning mother-love.

Anyway, Plato didn’t have to be all that original in ascribing incestuous wishes to people. A year or two before he was born, the Athenians watched Sophocles’ great tragedy about Oedipus, whose mother/wife Jocasta says “Men have long slept with their mothers in their dreams”—not as if she were revealing anything new, but as something commonplace.

Bringing this revelation into a description of romance is a way of saying that this man or woman you feel so in love with is a substitute. The story had warned that you might need to find a replacement to love, because common sense says that you might not ever find your other half.

By linking it to infantile desire, Plato changes the whole image of falling in love. Instead of the long familiarity of growing up together, we’re talking about an older familiarity that says “I never grew up.”

What about the third detail? It’s awkward and it slows down the action to say that people were split in half, only later to have their genitals moved around so that they could see this fact about themselves, becoming sexual creatures in the process. As part of a streamlined narrative, it is clunky. But it does click as psychobiography. After the first separation from your mother, you languish, helpless. As a child you experience yearning without knowing where it comes from. Only in puberty do you become aware of yourself sexually, as if for the first time seeing your genitals for what they are.

Sure, it’s impractical to think that there is a single person just right for you. From philosophy’s point of view, as Plato understands philosophy, those other attacks on romance still hold true. But he is also canny enough to write a rival’s tale of romance that spills the beans about the forbidden desire behind it. If you want to see what’s wrong with that cult of romantic love, he’s saying, listen critically to the stories that people tell about it.

The legacy of romantic love is an old one. Valentine’s Day reminds us of that fact every year. Plato reminds us that there’s also an ancient legacy of exposing romantic love as something very different indeed.

You know how it goes… all ancient men hated women. Right?

And Socrates… well, he was a terrible husband. So surely that means he wouldn’t have anything nice to say about the ‘fairer’ sex.

And then, there is the Woman Question...

It’s a scene in Plato’s Republic…. The debate between Glaucon and Socrates is over what women’s nature, role, and political position in the human community is or ought to be.

The solution is notoriously unsatisfying.

Aspasia and Socrates

Indeed, most readers across time and space have found reasons to quarrel with it, whether by attempting to explain that Plato did not mean women to study philosophy after all, or by considering that the caveat of women’s relative weakness undermines the whole of the text’s treatment of women.

But what if…. Socrates (aka Plato) actually wished to educate women?

Perhaps even… gasp… with the goal of creating a Philosopher Queen?

It is this point that one of our Classical Wisdom Symposium speakers – the Assistant Professor at St. John’s University, Department of Philosophy, Mary Townsend – addresses in her excellent book The Women Question in Plato’s Republic.

It’s a book that may make you rethink your views on the Republic… and indeed Plato himself!

In the words of Emily Wilson, Professor in the Humanities at the University of Pennsylvania and British Classicist famous for her Odyssey translation:

“Townsend’s book should be required reading not only for classicists and ancient philosophy scholars but also for political theorists and people interested in gender studies more broadly.”

You can get your own copy here.

Listen to Mary speak live on… Pleonexia.

What is Pleonexia??

First, let me ask – why are we humans almost never satisfied with what they have?

Even after major successes, why do we continue to find new avenues of desire?

The examples of this are endless… but we know in our hearts of hearts that we are all guilty of this.

Well, fortunately for us, Plato wrote many works that explore aspects of our desire for more, always more, the kind of wanting that was known as “pleonexia” in ancient Greek.

In fact, Plato shows us a way to transform our Pleonexia into a pursuit for the highest possible version of what we want: the Good Itself.

Make sure to sign up for our upcoming Symposium (One Week Away!) to learn all about Pleonexia and our desire for more…

NB: Our wine option has closed, but that doesn’t mean you have to miss out! In fact, you can get either the One Day or Two Day Pass HERE (now discounted!)

IMMERSE Yourself in the Ancient World… For a Weekend of Wit & Wisdom