The Three Elektras

Lysistrata:

You simply wash the city just like you wash wool.

First, you put the wool into the tub and get rid of all the daggy bits, all the crap around its bum. Then you put it on a bed, take a rod and scrutch and bonk all the burrs and spikes out of it. All those burrs and spikes that have gathered themselves into tight knots and balls and are tearing and tangling the wool of State, well, you just tease them all out of there. Rip their heads off! Then, off for the combing. You put all the wool together into one basket. All of it! Friends, foreign or local, allies -anyone who’s good for the State. Drop them all in there. As well as our citizens from the colonies. Consider them, too, as part of the same ball of wool, only separated from each other. So, what with all those colonies joining the ball, you’ll be able to weave a cloak big enough for the whole city. (Lysistrata, 575ff, author’s translation)

“Then people also say that while we live quietly and without any danger at home, the men go off to war. Wrong! One birth alone is worse than three times in the battlefield behind a shield.” l. 249ff

Written By Walter Borden, M.D., Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Aeschylus speaks to me. Born in Eleusis, a village just north of Athens and the haunting grounds of the goddess Demeter, said to be the goddess of fertility and the harvest. To Aeschylus that was just a myth that masked her true identity—the goddess of grief. When he was a little boy crying at the grave of his grandfather, she’d whispered to him that his sadness and tears would make the soil rich, would bring new life to sprout.

Only the citizens of Eleusis were aware of Demeter’s real meaning—and mission. She’d lost her daughter, Persephone, to a plague, but Demeter felt it as a robbery—her baby stolen by a death she called Hades, god of the underworld. He was the evil of ancient times. She vowed to find her daughter, bring her back, to her arms, to life.

The citizens of Eleusis were sworn to secrecy, never to reveal her grief—it was too agonizing. Their oath of secrecy became the cult of the “Eleusinian Mysteries.”

As a citizen of Eleusis, Aeschylus knew all that, but he revealed the secret of the mysteries in one of his early poems. For breaking the oath of secrecy he was prosecuted for heresy in an Athenian court under a system of public democratic justice, established by Solon some hundred years prior. Aeschylus was found not guilty. The jury decided that grief outweighed guilt. After experiencing Athenian justice personally, he became its powerful spokesperson.

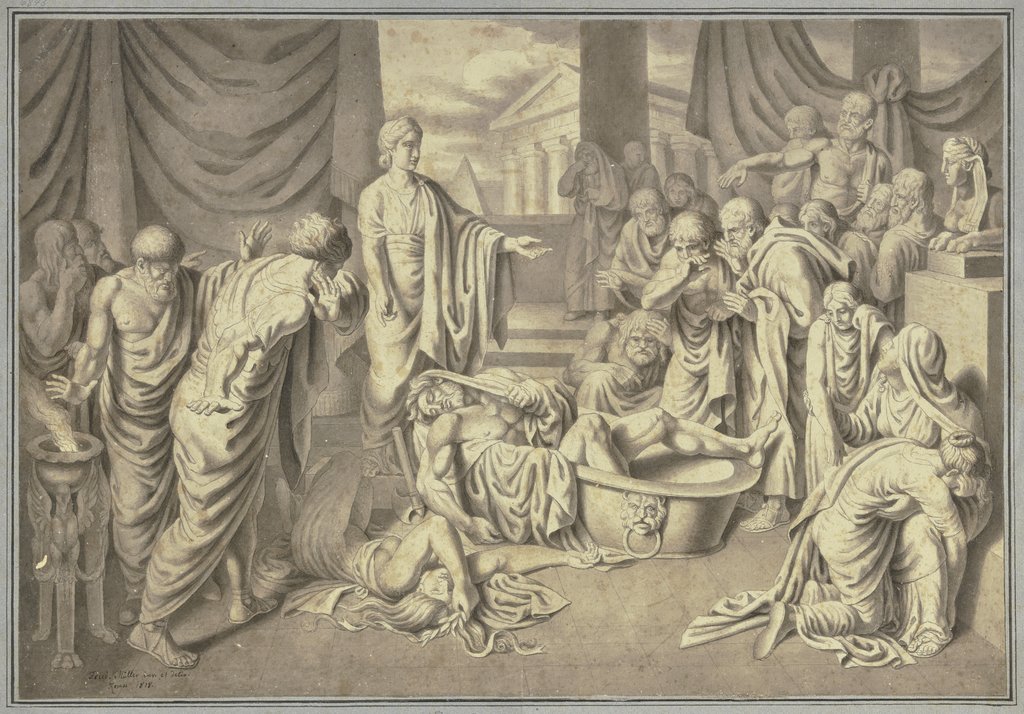

Having killed his mother, Orestes is Pursued by the Furies, by William-Adolphe Bouguereau

Aeschylus later gave Persephone’s mysterious death his creative twist. Plague and death were thought to be a calamity wrought by the gods. The popular explanation was that Hades, the god of the underworld, abducted Persephone. Aeschylus thought this was the storybook way of saying the girl’s dying must have a sinister, but purposeful source. Indeed, even today, do we not explain senseless tragedy by attributing it to evil? Aeschylus said that people blamed the gods when something inexplainable happened. Did it simply mean that to lose someone really close was bad, and could make you feel bad?

In his metaphorical dramatic interpretation, Demeter and Persephone couldn’t accept losing each other. Their bond was so strong; grief endured and lashed them together. They pined, persisted, persevered, and then—a miracle. Their grief-bond seemed to ferment and come alive in a new form. New life sprouted. They called it Spring, the time of fertility. Followed by a time of growth, Summer, and then harvest, Autumn. Cold set in, snow. Winter, the earth rested waiting for the return of Spring. The seasons came to be, cycles of life and death. The “Mystery?” It’s about fertile grief, how grief can bring new life.

Aeschylus’ best writing germinated in his personal tragedy on the plains of Marathon fighting the Persians. He saw his beloved brother, Koryenous, hacked to death by the Persians. He suffered grief which fermented—metabolized—blossomed (sprouted if you will) in his drama.

Die Seeschlacht bei Salamis [English: Battle of Salamis], Wilhelm von Kaulbach, 1868.

Of his ninety plays, only seven survived. They are all we have of his work, and there is controversy as to when each was written, except the first and the last. The Oresteia was produced in 458 BCE, two years before his death. The first was probably The Persians, the only non-mythological play, written shortly after the Battle of Salamis, in 480 BCE.

Aeschylus’s profound insight was the importance of freedom to speak one’s mind, as a generality, but especially in expressing the pain of loss, that unspoken grief is unresolved grief that can become madness and murderous retaliatory rage, breeding more violence. He is said to have observed that words are like a physician to the mind gone mad. From his own life and personal pain, in the Oresteia, he created a tragic drama that touched the deep need for psychological healing in a people that had experienced overwhelming losses from terrible wars, plagues, cycles of retaliatory violence, and the impact of social changes as the Bronze Age gave way to early modern civilization.

Mosaic of Orestes, main character in Aeschylus’s only surviving trilogy, the Oresteia

Aeschylus was the first tragedian, but also soldier, democrat, social critic, psychologist, and philosopher. Called the religious or moral tragic dramatist because of his focus on crime and punishment and on personal responsibility for destructive behavior, he could more accurately be described as a psychologist of conscience.

As a dramatist of crime and punishment, he was the first to stage a courtroom scene, and he knew personally what it meant to be wrongly accused, since he had been charged with heresy for revealing the secrets of the mystical Eleusis, later vindicated in a law court. His genius combined psychology and sociology in the context of historical development, reinforcing his message with the arts of dramaturgy, staging, poetry, music, and choreography. He marketed justice with appeal to the senses as well as the mind.

There is very little known of a biographical nature except that his father, Euphorion, came from an old aristocratic family in Eleusis, near Athens. Of his two sons one became a dramatist. His sister was the matriarch of a dynasty of tragic dramatists. The lineage raises interesting questions about this family who wrote with so much insight about the importance of relationships and family issues.

Ruins at Eleusis, Greece. © Emmanouil Pavlis/Dreamstime.com

Although the women were invisible, Aeschylus’s sister could not have been an inconsequential person, and her brother’s work portrays some very strong female characters. Athena, who speaks for Aeschylus in the Oresteia, is the play’s most powerful figure, overshadowing Zeus and Apollo. The injustice to women in Greek society and its destructive impact on them and the community is the theme of his Suppliants and a subtheme in the Oresteia.

As an adolescent, he lived through the overthrow of Pisistratus, the murder of the latter’s son Hipparchus, and the establishment of the democratic constitution of Cleisthenes. It was a turbulent time: Persia was mobilizing to attack Attica, the Athenian heartland. Aeschylus became a soldier and fought in the infantry at Marathon and Salamis. The Persians was produced ten years after Marathon and immediately after the victory at Salamis. The Oresteia and Seven Against Thebes are strongly antiwar, and the themes of war’s waste of innocent lives and unresolved grief resonate throughout. In The Persians, he dramatizes the Greek victory as a mastering of a savage hubris latent within the victors. He also attacked the glorification of war in the Athenian celebration of the victory over Persia.

Until Aeschylus, drama was two-dimensional. In the ancient epic/lyric form, there is one actor, the hero, and the chorus, which represents some facet of the voice of humanity. The hero is defined, and engulfed, by external forces that grow stronger as he struggles against them. The character of the hero is almost irrelevant; he is pushed and pulled by destiny’s demons. The chorus, a communal voice with a character of its own, is the protagonist and defines the issues—usually grand communal themes, such as the polis, the defeated and/or the victimized—by focusing them on the single actor through a prism of moral force. Chorus and actor are in reciprocal relation.

The Murder of Agamemnon by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1817)

As the crisis develops and tension builds, the focus shifts. The actor becomes protagonist, the center of the moral struggle, which ends with the hero facing the crisis and making his decision. In the lyric epic, the initial situation never changes. The plot remains the same as in the first ode, when the actor enters and reveals the general situation. There is no moving plot. The only action is the increasing tension within the hero. There is no way to change perspective.

In a creative leap, Aeschylus adds a second actor, which brings movement to the plot and shifts the focus onto character. The second actor introduces new information, such as relevant events that would be impossible for the hero to know, events that may drastically change his circumstances. An old family employee can come onstage with news that the hero’s wife is really his mother, or a messenger arrives to tell him that the presumed dead son is alive and has returned with murder in his heart, or that the opponent he is going to fight to the death is really his brother. The plot moves and thickens. Moreover, interactions between characters add definition and dimension to their development.

In another creative leap, he modified the structure of the trilogy, linking three plays in a series with a unified theme. The concept of linked acts—action over time with continuity of motif—enables evolution of plot and issues associated with the generation of inner drama in the hero. Trilogy, as used by Aeschylus, can best be understood as the ancestor of the three-act play.

Electra and Orestes at the grave of Agamemnon. Greek tragedy by Sophocles. ©Ronald Sheridan/Ancient Art & Architecture Collection

Using this structure, he was able to portray the transfer of influences from person to person, generation to generation, within a family and within a people. Change, growth, and decline was brought to life on the stage. He could dramatize the legacy of emotions—a sense of obligation, a sense of guilt—that passed from fathers to sons and daughters and on to future generations. He could depict the harbingers of madness and the long-term effects of grief, abuse, conflict, and violence—thus showing that retaliatory violence, even in the name of justice, only breeds more violence, that oppression of women and children makes them violent in turn, that brutality is destructive to society. He was able to show that unspoken grief results in an inability to come to terms with the past and leads to the reenactment and perpetuation of old conflict and pain. His dramas are the first psychiatric studies.

Aeschylus helped lay the foundation of psychodynamic psychology. He was also a consummate advocate for the incorporation of psychological understanding in democratic justice. He dealt with the issue of criminal responsibility when madness is an element of criminal behavior. Guilt had deep roots in Hellenic culture, stemming from the primitive conviction that the gods—Zeus in particular—would take revenge on any mortal who offended them. In Homer’s time, guilt was associated with the anger of the gods; extenuating circumstances and motivation were irrelevant; psychological issues were irrelevant. Only the act counted, and punishment was absolute. The Furies were the gods of vengeful punishment and could drive the offending mortal to ate, guilt-ridden madness.

Orestes at Delphi, flanked by Athena and Pylades, among the Erinyes and priestesses of the oracle. Paestan red-figure bell-krater, c. 330 BC.

As psychological understanding evolved, ate was seen as arising within the human mind rather than having been put there by the gods. Furthermore, guilt—and by extension, depression—was seen as impairing thinking and judgment. The orator and legislator Lycurgus (390-324 B.C.), in Against Leocrates, quotes an unnamed poet:

“When the anger of the demons is injuring a man, the first thing is that it takes the good understanding out of his mind and turns him to the worse judgment, so that he may not be aware of his own errors.”

Aeschylus refined this notion into the theory that the guilty could unknowingly seek punishment. Guilt and despair were not seen as visitations from the gods but as an internalized sense of wrongdoing that could rise to the level of ate─that is, reach such intensity that it became insanity.

There are crimes that arise from a sense of guilt, and some criminal behavior is a seeking of punishment. While Solon planted the seeds of psychology in justice; Aeschylus cultivated and helped shape the growth, giving clear and dramatic power to a basic element buried in Solon’s legal code: that the substance of justice includes humanism—that is, compassion, mercy, respect for the person, for the rights of the weak, and at the same time dispassionate psychological understanding.

The transformation of the passion for retaliatory violence into a higher order, a system of rational justice, began in the seventh century BCE and was institutionalized by Solon in the sixth century. Aeschylus dramatized this transformation in the fifth century, distilling and refining the psychological elements of Solon’s justice, giving them a powerful voice. Solon separated theology from the administration of justice for the first time in human history, and took the gods out of the law.

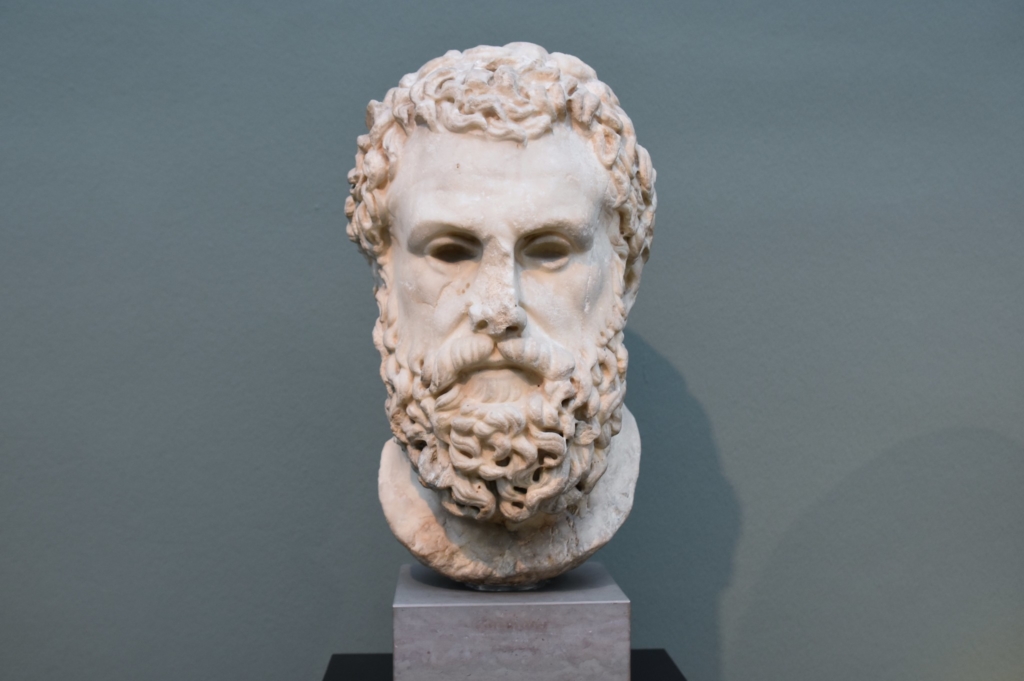

Roman marble herma of Aeschylus dating to c. 30 BC, based on an earlier bronze Greek herma, dating to around 340-320 BC

Aeschylus used the gods as symbols; his religion is secular, reflecting the evolution of the theology founded on Zeus’s law, “to the doer be done”—the Greek equivalent of the Hebrew “eye for an eye”—into a new institution of justice and a moral code based on human psychology. In the Oresteia, Zeus, Furies, and Apollo are symbols of the old order; Athena is the new; they are clearly dramatic symbols, not to be seen as real deities. As Solon had done with his legal code, Aeschylus dramatically brought the laws of Olympus down to Earth so that they could be seen inside men and women, understood, and elaborated in a system of public justice.

He dramatized the development of mature conscience and its relationship with law. The gods do not direct human actions; the direction comes from within. The individual, not the gods, bears all responsibility, but responsibility is not absolute, as under Zeus’s law, nor should punishment be absolute. The mature sense of responsibility, conscience, is rational—meaning actions directed toward others are determined by reason and empathy tempered by values.

Aeschylus dramatically portrayed the transition of values from gods to parents and the identification with those values within the family. Empathy and parental identification are at the core of a rational sense of right and wrong and the ability to anticipate causing harm. Rationality also means that all relevant circumstances have to be considered, and that there are degrees of responsibility. Circumstances, such as chance, accident, motivations, intent, harm done, and psychological understanding are factored into the equation that the mature rational mind uses in assessing guilt. There are degrees of guilt, and punishment should be proportional. These conditions are integrated in the rational sense of responsibility called conscience. While for the most part conscience and law coincide, they may differ, and even conflict. That is the stuff of tragedy, too, and Aeschylus is its master.

Written by Stella Samaras, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom Weekly

“The poet’s grace, the singer’s fire,

Grow with his years; and I can still speak truth

With the clear ring the God’s inspire…”

Aeschylus, Chorus from Agamemnon

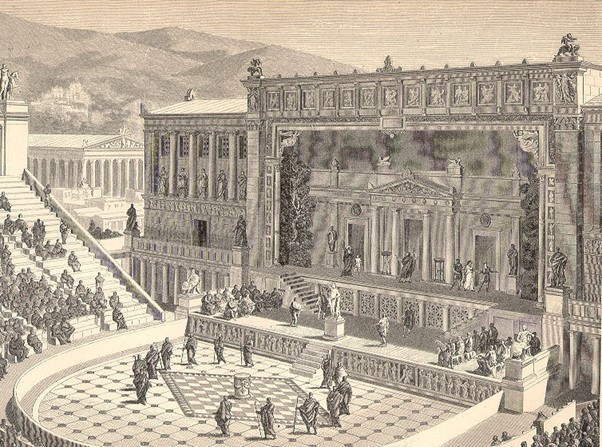

In 458 BCE, the aging Aeschylus was a contender at the Dionysia. Athens, although enjoying peace between the Persian and Peloponnesian wars, was undergoing political change. Aeschylus had a word or two to sing about it. With the Dionysia on his radar he knew he had a wonderful outlet to be heard and an opportunity to persuade the masses toward empathy and reason. He also had his eye on the annual prize. He was in it to win.

The Context: Areiopagus vs Heliaia

To achieve both ends he needed to employ a thinly veiled allegory in the guise of a story from antiquity. You see, his thoughts touched upon the stripping of power from the old and well-established council of nobles, the Areiopagus, and its replacement by the more populist court of citizens, the Heliaia. The reform reduced the Areiopagus from a legislative power to just bringing down rulings on murder.

It was a touchy subject, the transference of power, the loss of honour. How to approach it? Which myth would serve his purpose? Something set during the war of the Titans, the time when the patron goddesses of the Areiopagus, the Erinyes (Furies), were born? Hmm…maybe not.

Northern Elevation of the Acropolis seen past the Areiopagus Hill before it centre left, 1888 photograph by Adolf Bötticher [Public domain]

Perhaps he could pitch his views in the mythical battle between Poseidon and his niece Athena? The battle was cross-generational and pertained to Athens but the scope for pathos was limited. No, the Festival called for something with more oomph.

Justice and Vengeance

Straight social commentary and pandering wouldn’t win him the prize at the Dionysia. The winning triad of plays had to provide something more, perhaps a discussion of a higher principle, one that was at the core of what the Areiopagos and Heliaia were about: an eternal principle—justice.

Should the law circumscribe behaviour by meting out justice retrospectively in acts of revenge and risk perpetuating vendetta? This was the old way, the way of the Furies whose curses and mad retribution scared Athenians into behaving. Or should justice be meted out in an Athenian court where revenge had no place and couldn’t self-perpetuate?

Aeschylus would write a cycle of three plays for the festival to hammer his point home. His story had to capture Athens’ attention: it had to establish the roots of a crime, grapple with the ethics involved, see its consequences play out, and then provide a denouement that would satisfy, cleanse, and teach. The first play would have to be tantalising, capturing their imagination and holding it through to the end of the third.Hmm…which myth? Troy?

A Cursed House

With the Areiopagus in mind, the story had to deal with murder, but not just any murder. It had to be an act of retribution and to the minds of some, a justifiable act. Could the death of Agamemnon fit the bill? He lied to his wife, Clytemnestra, to enable him to entice her to bring their daughter Iphigenia to Aulis where the restive Greek army awaited the winds to rise. She was to be a bride for Achilles, he said.

Instead, father sacrificed daughter at the altar so his army could set sail for Troy. Ten years passed and Clytemnestra and her lover, Aegisthus, Agamemnon’s cousin, were well prepped to avenge the murder. Once the deed was done, Orestes and Electra were compelled to avenge the death of their father with the death of his murderers.

Of course, the house of Atreus (Agamemnon’s father) was already cursed when Atreus served his brother, Thyestes, the bodies of his children in a meal. The crime was atrocious. Until Aeschylus’ treatment of the myth, Aegisthus, the eaten boys’ younger brother, avenged them by being the one to physically plunge the sword into Agamemnon.

However, Orestes avenging his father by killing a figure of such low esteem as Aegisthus would not elicit the pathos needed for a powerhouse production. Aegisthus was a coward, who took no part in the war but stayed at home and courted his soldier/cousin’s wife.The Mannish-Woman and the Womanish-Man

In a stroke of genius, Aeschylus flipped the perpetrator from being a craven man to a strong woman and mother of the avenger. By placing the net and sword in Clytemnestra’s hands he heightened the dramatic tension, the pathos of the play, and highlighted the issue with calling on the Furies to provide justice.

When father killed daughter the family was cursed anew. His wife avenged their daughter as justice had to be served. The next course of justice was son killing mother. Without the intervention of the Athenian council the chain of killings would not be broken, for the justice of the Furies must needs be served regardless of the will of s/he who is called to serve it.

“If pity lights a human eye

Pity by Justice’ law must share

The sinner’s guilt, and with the sinner die.”

By making Clytemnestra the instrument of justice, Aeschylus faced another challenge: the audience accepting her as an equal to a man. When he refers to her in terms such as, “…Clytemnestra, in whose woman’s heart a man’s will nurses hope,” he is not making a feminist stand. Had he intended to make such a political point he would not describe Aegisthus, who he clearly has an aversion to, as:

“You woman! While he (Agamemnon) went to fight, you stayed at home;

Seduced his wife meanwhile; and then against a man

Who led an army, you could scheme this murder!”

Aeschylus, in trying to maintain a strong argument against vengeance as a form of justice, had to accord as much honour to each victim/perpetrator. He could only do this by elevating the status of Clytemnestra to be equal to a man. The choice may have perturbed some.

Fate, the Sanctity of the Guest-Host relationship and a Middling Course

Having conceived a vital plot line, Aeschylus had recourse to tragic tropes to strengthen his play. By repeating the story of Atreus and the death of Iphigenia he reinforces the role that indelible fate plays in driving the inevitable.

From the outset, Aeschylus pummeled his audience with foreboding, remembering past wrongs of the family but also connecting the family curse of Atreus with Paris’ transgression, stealing away with Menelaus’ wife, Helen. Menelaus was a son of Atreus too. By reliving his grief and the consequences of the ten-year war, Aeschylus built on a sense of ill will and disharmony.Compounding the sense of impending doom is the act of hubris Clytemnestra easily convinced Agamemnon to do – by treading on the costly tapestries she had strewn before him, he overreached his measure as a man and a king. He put the gods offside. By the time the audience is presented with his prostrate corpse, the suspense of having to wait for the inevitable has reached fever pitch.

Would all this be enough to put Aeschylus’ play on a winning path? Well, he did have more to offer.

Imagery

Aeschylus’ imagery reached out and touched his fellow citizens and even reaches forward to us today. Whether he is describing the conditions of a campaigning soldier, the heartbreak of an abandoned spouse, or the plight of old age, his imagery is poignantly relatable.

Did he do enough to win that year? Yes. Did he get his point across with logos, pathos, and ethos? Did his audience leave the theatre renewed by a cathartic experience? That would depend on the veracity of his actors and his music. For a victorious playwright, I’d like to imagine that they did.

By Jocelyn Hitchcock, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The Frogs, an ‘old’ comedy play by Aristophanes, was performed in 405 BCE at the Lenaia festival of Dionysus. With the Peloponnesian War raging on, plays of the time had a tendency to deal with saving the state, matters of right and wrong, and background events of the war itself. Writers focused on political themes, pushing the idea that a poet has the ability to save the state from war.

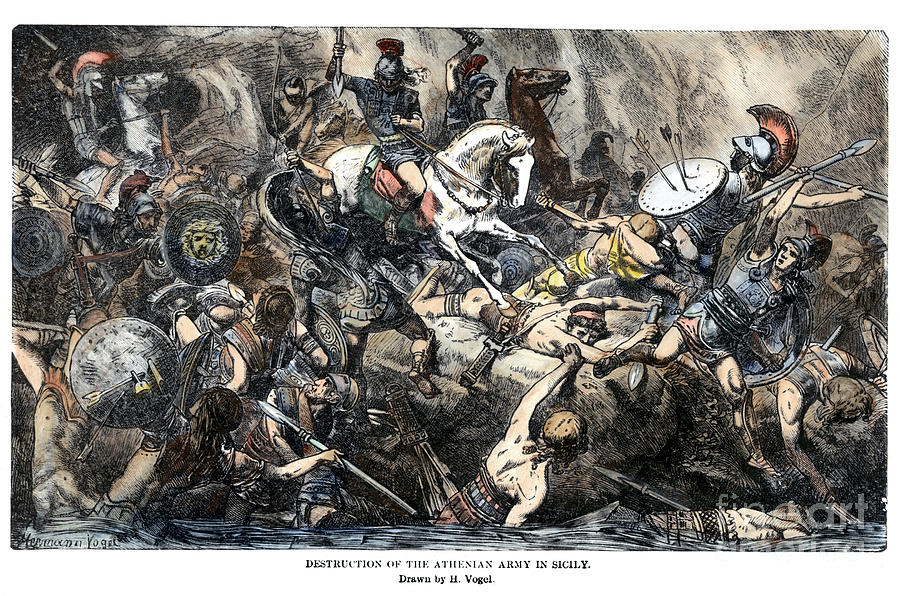

Peloponnesian War, where Athens suffered tragic defeat

The Plot of Aristophanes’ The Frogs

Originally disguised as Heracles, the god Dionysus ventures down to the underworld to seek out Euripides, the tragic poet who had died in the previous year. Against the backdrop of war, Dionysus thinks that Euripides is the only one who can safe Athens from itself. Dionysus crosses the lake with Charon while debating with a chorus of frogs along the way.

the Self-Portrait as Bacchus, is an early self-portrait by the Baroque artist Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, dated between 1593 and 1594.

Soon, the issue of Dionysus’ disguise as Heracles presents itself when he realizes Heracles made a few enemies in the underworld. Accompanied by his slave, Xanthius, Dionysus makes him wear the costume instead. Then Xanthius, dressed as Heracles, gets invited to a banquet of feasting and dancing. Dionysus, not surprisingly, wants to be the one at the banquet so they swap clothes yet again. However, at the banquet Dionysus dressed as Heracles makes even more people mad, so they switch again. This whole first half of the play is mostly Dionysus’ fumbling with choices, making Xanthius cover for him and improvising to right his wrongs.

Red-figure vase painting showing an actor dressed as Xanthias in The Frogs, standing next to a statuette of Heracles

As the play progresses, Dionysus finds himself in the palace of Pluto where Aeschylus and Euripides are competing for the best tragic poet. Dionysus acts as the judge while Aeschylus and Euripides quote snippets of their verse, critique, and respond to one another. In the final judgment of the debate, a scale is brought in and whichever poets’ words have the most weight to them will cause the scale to tip in their favor.

Ultimately, this measuring device proves ineffective and Dionysus asks the battling poets to provide advice for how to save the city. In the end, Aeschylus proves to be more practical and suited for the job, so Dionysus chooses to take him back to earth.

Bust of Aeschylus

Key Themes in Aristophanes’ The Frogs

In this play in particular, Aristophanes unequivocally posits that it is the poet’s duty to save the city. However, this is fully dependent on defining who is the right poet, who has the right ideas, and who makes the right decisions. This is expressed through a series of choices, disguises, and deceptions throughout the play. Dionysus is the butt of the jokes in the first half of the play, constantly going back and forth with Xanthius and constantly making the wrong choice.

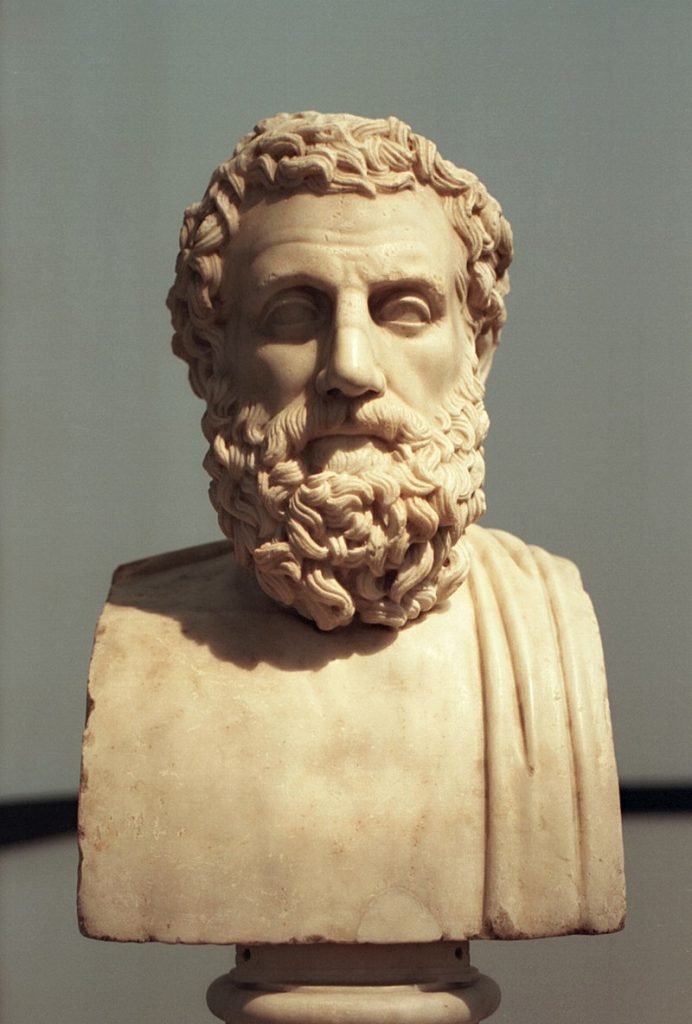

Bust of Aristophanes

In the second half of the play, Dionysus transitions into a stoic, perceptive judge of others. His final choice of Aeschylus is left up to the audience to decide whether or not it was the right decision. Aristophanes also leaves the success or failure of Aeschylus to save the city open-ended. Aristophanes is intentionally ambiguous and subtle, which the audience no doubt would have picked up as a larger comment on the present day backdrop of war. Aristophanes manipulates the reality that his plays are set against, providing audiences a transcendent view of truth.

The Reception of Aristophanes’ The Frogs

The Frogs performed by The Barnard Columbia Ancient Drama Group

Having won the contest in 405 BCE, the Frogs was a comedic hit from the beginning. Some sources even suggest that Athens commissioned in the same year for the play to be put on again. The Frogs is also commonly performed in modern day theaters, being adapted into musical form as well. The onomatopoeia of the frog croak, witnessed in the choral ode of the play, has been used in Finnegans Wake by James Joyce, and was referenced in Jesting Pilate by Aldous Huxley.

It is clear that Aristophanes’ The Frogs was a great success. The fact that the raging Peloponnesian War ended the year after, however, probably didn’t have much to do with it, despite the Poet’s attempts.