By Jocelyn Hitchcock, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Once upon a time there was an epic 10-year war between austere and grandiose powers of the Mediterranean. There’s the wrath and favor of gods and goddesses, love and heartbreak, hope and despair, victors and losers, and, of course, the horse.

Detail from The Procession of the Trojan Horse in Troy by Domenico Tiepolo (1773), inspired by Virgil’s Aeneid

We can only be talking about one story – The Trojan War. Traversing languages and lands, the author (or more likely, authors and groups of creators over generations) that created the Iliad and the Odyssey wove a tale that spoke so loudly to the psyche that it is still pervasive in many aspects of today’s popular culture.

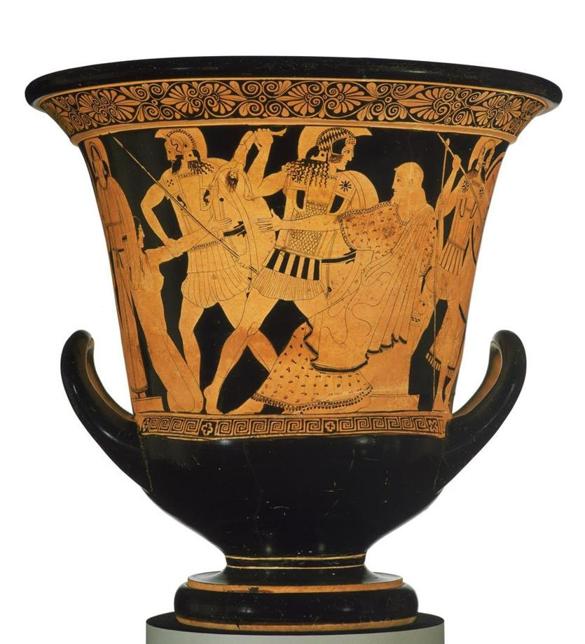

Once an epic spoken to the tune of music and recited from memory by bards, the Iliad and the Odyssey were committed to writing sometime between the 8th and 7th centuries BCE. In the ancient Greek world, scenes of the Trojan War were already a popular subject among artists. Vase paintings, wall decorations, and other works of literature that stemmed from the premise of Homer abounded. Scenes of the war appeared on clay kraters, a type of vase that was intended for use at a symposium. Here, the men in attendance would lounge around, look at the scenes on the krater, and it would spark discussions on topics such as bravery, war, religion, and whatever else is alluded to on the vase.

Mixing bowl with scenes from the fall of Troy. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

But let’s fast-forward a few millennia. We know that the Iliad and the Odyssey have been incredibly popular topics throughout time, or else our fascination with them today might not be as deep. Permeating the crust of our own day and age, we have the Trojan War represented very clearly in films titled (unambiguously) Troy (2004), Helen of Troy (1956), and The Trojan Women (1971), to name a few. We see representations of the epic in video games and comics, the most recent sweeping the United States being the Assasin’s Creed: Odyssey.

And, of course, in our era of television studios churning out material like the medium will die tomorrow, we have many adaptations visible on TV, from the Disney Channel cartoon, Phineas and Ferb to dramatic retellings like Netflix and BBC’s Troy: Fall of a City.

Troy: Fall of a city

So, we know that the Homeric epics are popular springboards for creative fodder, but how have the representations outside the texts transformed and altered our common understanding of the Trojan War itself?

I am by no means a “classical purist,” and my bias may show in that I enjoy a good adaptation and creative twist to a classic – something also seen in antiquity several times over. While some in our field may look at representations like Troy: Fall of a City as preposterous misconstructions of the beloved Homer, I choose to appreciate them for the medium they are created in, knowing full well that a direct adaption is a ridiculous notion and that the epics themselves faced “personal spins” in antiquity, depending on the audience.

Bust of Homer

For those that are well acquainted with Homer, they may be quick to jump on the inaccuracies of pop culture adaptations. In Troy: Fall of a City, for example, there are many.

For starters, the level of interference played by the gods illustrates a strong difference between the film and the text. From central and imperative to all but dismissed, Troy: Fall of a City begins well enough with the divine characters, but soon loses track of them amongst the hubbub of other plots.

This is, of course, in stark contrast to the involvement we read in the texts themselves, where the gods are central and meddle, even when instructed not to be involved. While we certainly might have wished to see more of the gods throughout the series, they did seem to fade away naturally in favor of mortal plot lines. It was a decision that seems to align with viewers’ desires, to identify and see the people of the story, to make the heroic epic seem more like a historical event rather than, well, an epic.

Athena counseling Achilles in “Achilles’ Wrath” by Michel Martin Drolling

Another common discrepancy we see, and as many reviewers have pointed out, is the scene where Achilles stands outside the Trojan walls and screams for Hector, who is inside. Very much a focal point in Troy: Fall of a City (and a bit of a tearjerker, if I do say so myself), this soul filled wail is not what was written in our source material.

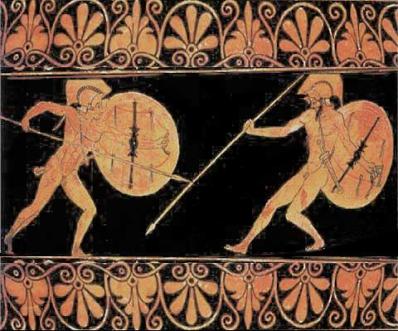

Instead, Homer writes that Hector was the only soldier of Troy to remain outside, with old King Priam begging him to come inside the safety of the walls. Hector, however, remained and met Achilles face-to-face. So, while the screaming for Hector is an aspect of our adaptations we see repeatedly, and for good cinematic reason and reception, it is not one based in Homeric truth, whatever that may be in the first place.

Achilles and Hector

This brings us to the classic icon of the Trojan War, one you probably learned about in the 4th grade with quaint cartoons mapping it out: the infamous Trojan Horse.

We have come to know the Trojan Horse as a symbol of trickery, deceit, war, and both victory and crushing defeat. Pop culture representations of the horse’s entry may vary from work to work, but, at least here, the pretense remains the same; the Trojans are taken off guard by the Greeks hiding inside the horse, who are able to deliver a deafening end to the war once they are secretly brought inside the gates. This symbol of the war stands out far above the rest, with the term “Trojan horse” coming to mean things in our modern world of technology, coding, war, and general social commentary. The attack represented a myriad of things then, as it does now.

Replica of Trojan Horse – Canakkale Waterfront – Dardanelles – Turkey

It is easy to look at a piece of pop culture and be overtly critical of its blind eye to what we may consider glaring inaccuracies. The Trojan War is ubiquitous with antiquity, war, and the Greek world. The literature, archaeology, and history have been mused over since before it was even committed to writing. Because of this prolonged obsession, modern culture is filled with examples of the Trojan War, including the glowing successes and of course, inevitable missteps. Nonetheless, the Trojan War and its accompanying themes of bravery, struggle, love, and fate all persist today, in just about any adaptation you pick up. I think Homer (whoever he or they were) would tilt a symposium glass to that indeed.

2 comments

Many classicists agree that there probably was no actual Trojan horse. Some have suggested that the reference may be a carefully crafted story twist on ancient siege engines, which were often covered in wet horse hides to prevent them from catching fire. Others have suggested it might have been a battering ram shaped like a horse. Still, others have opined that the horse is purely metaphorical and actually represents an earthquake, as the god Poseidon was both the god of earthquakes and of horses. Because there are so many myths running through the entire story of the Trojan War, we may never know the truth. Regardless, the idea of the Trojan horse is obviously a good piece of visual storytelling, which must have captivated ancient audiences’ imagination.

The myth of Troy is also a Tragedy because both the main heroes, Hector and Achilles, have died in it.

And both them were good and bad…in the Illiad…

The movie is struggling to show the essence of what the myth really is about…

Pieter J (PJ)

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.