by Danielle Alexander, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

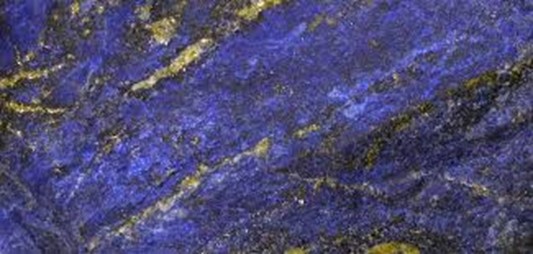

The immense trade routes of the ancient world allowed for substantial amounts of wealth, knowledge, innovations and mythological tales to traverse vast distances. Cultures often adopted items and ideas from far-away lands and repurposed them for their own needs. The semi-precious stone lapis lazuli was a highly sought-after item in the Bronze Age (c. 3300 BC – 1200 BC) trade networks, imbued with divine significance and symbolism.

Classicist R. Drew Griffith believes that lapis lazuli gained such an enchanting status due to its bright blue colour that mimicked the sky, the home of the gods: “brilliant by day, and deep blue flecked with stars by night” (Griffith, 2005:333). This view of lapis lazuli is identified throughout the Eastern Mediterranean, Egypt and Mesopotamian regions during the Bronze Age, but did this divine attribution appear independently across the cultures, or is lapis lazuli an example of how deeply trade networks can influence cultural hybridity and interconnectivity?

Lapis Lazuli: the Stone of the Sky

The name ‘lapis lazuli’ is an amalgamation of Latin and Persian meaning ‘blue stone’. The craftsmen who work with lapis to carve sculptures are deemed exceedingly skilled due to difficulties drawing out the aesthetic capacity amongst the abundant mineral impurities; these impurities are the cause of the characteristic ‘flecks’ amongst the deep blue.

The ancient market for lapis lazuli boomed in central Asia, the Persian Gulf, the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia, and from here it then traversed through the ancient Near East to the eastern Mediterranean and Egypt. Even before lapis reached these regions from where it was mined in the Badakhshan region (modern-day Afghanistan), some fifteen hundred miles away, it would have gathered a narrative connected to its journey.

Unfortunately, after the route between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley crumbled, the complex societies in the Iran region disintegrated during the first half of the second millennium BC and lapis lazuli became a scarce, prestigious good.

Image: DailyArtMagazine

Religious and Regal: Lapis in Mesopotamia

Allegedly, lapis lazuli first reached Mesopotamia during the Ubaid period (c. 4500 – 3500 BC), when the region experienced an exponential increase in wealth and leisure time that state emergence had allowed. Furthermore, the development of an effective administration ensured that long-distance trade and close cultural relations were well-maintained.

The mountainous route from the Indus Valley and Iran to Sumer is sprinkled with evidence of lapis lazuli. However, the rich deposits are mostly restricted to cities, with the smaller settlements of the region only producing handfuls of the stone. This treacherous route was only open for half a year, meaning that import was difficult.

During the Ubaid period, lapis figurines were prominently connected to the voluptuous female, or bull figurines, which are often connected to divine representation. However, after a socio-political power shift saw wealth annexed from the northern states to more southerly sites, zoomorphic figurines became more prevalent indicating a slight disconnection from the divine.

At Ur, the inhabitants emphasized religious architecture during the earlier periods of construction. Excavations of the religious precinct Eanna III revealed a hoard of lapis lazuli. This find demonstrates a direct link to lapis used within divine portrayals and ideology.

Scholars propose that the statues of Ianna, and possibly the goddess herself, were made of lapis due to a descriptive line in the myth of her descent into the Underworld. Unfortunately, there is no archaeological evidence to prove this claim, but it is thought that the lapis statues were recycled at a later date.

Inanna (known as Ishtar to the Assyrians) is further connected to lapis lazuli through a tale involving the second king of the First Dynasty of Uruk, Enmerkar. The goddess bequeathed a quest upon him; search for semi-precious stones, including lapis lazuli. After the king had successfully completed the quest, the trade route from Iran to Mesopotamia reopened and the lapis economy thrived once more.

Image: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

Excavations of the Royal Tombs of Ur have revealed a lapis lazuli bull figurine buried alongside a king, which is symbolic of kingship rites. Beside the king, lay his queen, who would have also been the high priestess. Amongst her grave goods, there were abundantly more lapis items than that of the king, which could indicate a strong link between lapis and the goddess Eanna through priestesses.

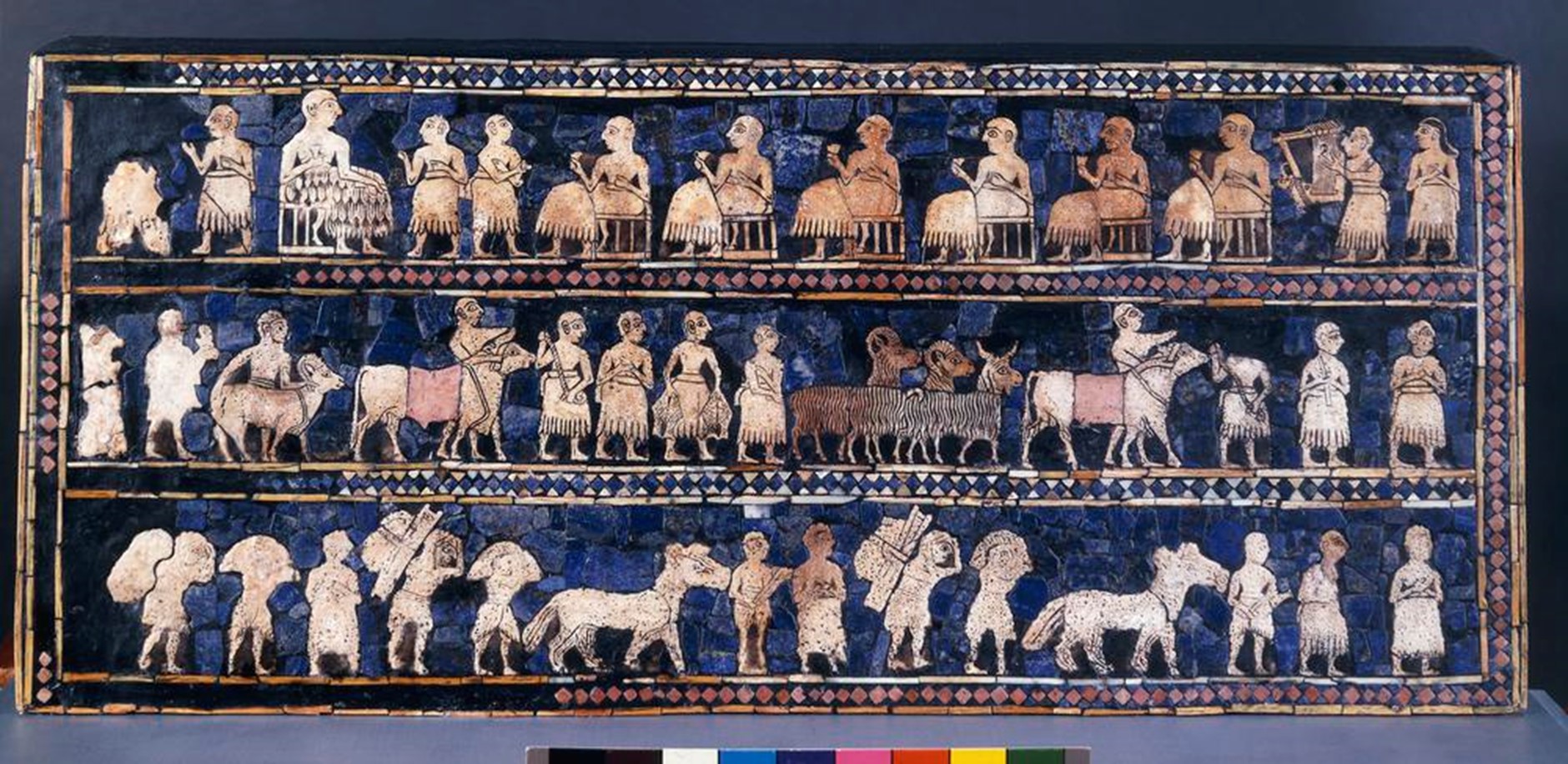

Below this royal family, another earlier grave housed a mosaic, named the ‘Standard of Ur’. The image is adorned with segments of lapis and portrays royalty and the divine manifestations of Peace and War. This indicates that lapis was used extensively in symbolising divine and kingship ideology. This notion is enhanced further by another mosaic found at the Ishtar temple at Mari, as well as rich evidence of lapis used in the gift exchange of royals.

For the early Mesopotamians, lapis symbolised status, both in divine and kingship realms. The Sumerian language links lapis lazuli, and its vibrant colour, to ‘the metal of the gods’, and remained a favoured material in the land between the rivers throughout its history. As the stone was traded to other regions, its significance to royalty and divinity journeyed with it.

Gods with Lapis Lazuli Hair: Egypt

Evidence of lapis lazuli use extends into the Pre-Dynastic period, although it was not very common. It disappears from the archaeological again during the 1st-3rd dynasties and is generally limited in Old Kingdom contexts, despite an Egyptian and western Asia trade route being well established by the 4th millennium BC.

However, this break in lapis trade appears to mirror the one in Mesopotamia, demonstrating the far-reaching impact of a discontinued trade route in an age of cultural interconnectivity. Not to be deterred by the lack of lapis, the Egyptians were the first to attempt imitations of the gold-flecked stone.

The largest predynastic find was discovered in the Main Deposit of Hierakonpolis but the finds are thought to be a manufactured in foreign lands, imported from sites such as Zahi (the coast of Phoenicia), Retenu (Syria), Isy (Cyprus), Naharin (Mesopotamia), and Assur (Assyria).

During the Old Kingdom, lapis is often found with old, but rarely silver, within high-status graves, including royalty, indicating high value and possibly connections to divine ideology. This is affirmed by grave goods found in the tomb of Djer, where lapis figurines of Sekhmet and Anubis have been uncovered.

Image: The Petrie Museum.

A set of feline figurines (part of Langton’s Cat Collection) dating to the Middle Kingdom emphasise a connection between cat-headed deities and lapis lazuli. It is unknown whether these figurines represent Bastet or Sekhmet. Nonetheless, both goddesses are important in the Egyptian pantheon and indicate that lapis lazuli was highly respected.

In Egyptian art, blue was frequently used to represent kings, divinity and even the dead, who were accorded great respect: “gods’ flesh to be gold and their hair lapis lazuli” (Griffith, 2005:332). The king of the afterlife, father to Horus and husband to Isis, Osiris, was said to be made of gold and lapis lazuli.

This connection to the king of the afterlife is potentially why lapis was used to adorn the funerary masks of Egyptian Pharoahs, who were often divine in their own right. The most famous of these is that of Tutankhamun. Many small zoomorphic statuettes are also carved from the stone, while others are made from other materials but feature inlaid lapis lazuli.

The use of lapis within heavily religious royal funerary rites specifically, indicates the high status this stone was accorded in Egypt. This ideology may have been passed on as it journeyed through Mesopotamia; for example, Babylon deemed lapis lazuli as a sacred stone and its terminology was often used in reference to divine hair, for example, the Moon gods’ beard being of lapis blue.

Image: Hannes Magerstaedt

Artistic Experimentation and Literary Evocations: the Aegean

During the pre-palatial period (or Final Neolithic) of Crete, there is minimal evidence for lapis lazuli, except at the site Koumasa. During the later Early Minoan and Middle Minoan era’s, the semi-precious stone was rarely used, despite the abundance of other prestigious items being imported from the East such as gold, ivory and other semi-precious stones. These exotic goods were frequently deposited by the elite within religious contexts, such as votive offerings on altars.

The limited use of lapis lazuli could indicate the regal and religious significance had not reached Crete by this time. Or, because Crete was only just emerging as a major player on the Bronze Age board, it could not afford such a prestigious item.

The latter could be the case, for the Minoans understood the symbolic power that lapis lazuli had – this is shown by its use within the fresco known as the Ladies in Blue. The expense of the stone could be linked to the extensive maritime effort required to gain it along with the difficulties of working the stone if the Cretan lapidary craftsmen were not yet capable of handling the material with the necessary expertise to bring out its aesthetic majesty.

However, the craftsmen were determined to join the lapis market and do it with style. A sarcophagus found on Crete shows a hybridization of Minoan and Mycenaean iconography and is inlaid with lapis lazuli. The use of a sarcophagus implies also Egyptian influence. As time went on, the Minoans incorporated more and more lapis into their high-value goods.

Artwork attributed to the Myceneans, found in Boetia, is the first evidence of lapis lazuli on mainland Greece. The fresco was created using a technique born in Crete; buon fresco or the use of water to mix pigments and then applying them to lime plaster. The site where this painting was found was a specialised administrative centre, not a palatial settlement, which evidences the use of lapis outside its divine or royal context.

Nonetheless, it is thought that the Egyptians had a heavy influence on the Mycenean culture, with the latter respecting the antiquity of the former. It was more likely that the Greeks gained their representations of the gods from the Egyptians, rather than Mesopotamia, despite a lot of the Grecian mythology coming from Asia Minor.

Within the Classical literature of Homer, blue hair is a frequent feature of gods or heroes, variously attached to the scalp, forehead or chin. He used it when speaking of Poseidon, Dionysus, Hades and even several female deities; Thetis, Nike, and Thebe.

It is a common misconception that Homer never uses the word blue in his Homeric Cycle. However, older translations failed to understand the Greek conception of colour. Dark blue in Greek is “kyaneos” (often simply translated as ‘dark’) and lighter blue is “glaukos” (often translated as grey, but is more of a grey-blue).

The Greeks understood the colour spectrum as having ‘brilliant and shining’, white, black, red and dark. Colours were often described via different routes and more inherent to the thing being described – like the wine sea, meaning that the sea was more a tinted, intoxicating liquid rather than implying a red sea.

Hector and Odysseus, famous heroes of the Trojan war, also have blue-related epithets attached to them. Homer also uses the term when speaking of Achilles’ shield, which holds a wealth of cosmological symbolism, and the breastplate of Agamemnon. Both of these famous artefacts are entirely mythical for the time being, as they have not been identified in the archaeological record.

Image: Angelo Monticelli, from Le Costume Ancien ou Moderne, ca. 1820.

The references to lapis lazuli in connection with divinities and heroes, who would come to encompass part of the Grecian sense of identity, indicate the superior feeling attached to the colour blue, quite possibly due to the prestigious influence of lapis lazuli, which gained mythos with it as it traversed along trade routes.

Cultures of Connectivity

During the Bronze Age, cultures were trading items, ideas and innovations. Part of this age of exchange and experimentation was the transfer of artistic ideas and the development of multi-national iconographic styles and techniques. Amongst this immense cultural milieu was the symbolism of lapis lazuli and its attachment to divinity or royalty.

Often, a culture took an idea, or an item, and adapted it, making it their own. This was also incorporated into the existing understanding of the idea/item and provided another chapter to the tale of trade. Simply by following the path of lapis lazuli, it is evident that the cultures of the Bronze Age were involved in an interconnected network that caused the hybridization of the stone’s story, as well as cultural ideology.

References

Ben-Tor, A. (1991). New Light on the Relations between Egypt and Southern Palestine during the Early Bronze Age. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, (281), 3-10. doi:10.2307/1357161

Breasted, J. (1894). The New Found Treasure of the Twelfth Dynasty. The Biblical World, 3(5), 362-364. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.uwtsd.ac.uk/stable/3135127

Brysbaert, A. (2006). Lapis Lazuli in an Enigmatic ‘Purple’ Pigment from a Thirteenth-Century BC Greek Wall Painting. Studies in Conservation, 51(4), 252-266. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.uwtsd.ac.uk/stable/20619462

Burke, B. (2005). Materialization of Mycenaean Ideology and the Ayia Triada Sarcophagus. American Journal of Archaeology,109(3), 403-422. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.uwtsd.ac.uk/stable/40026119

Colburn, C. (2008). Exotica and the Early Minoan Elite: Eastern Imports in Prepalatial Crete. American Journal of Archaeology, [online] 112(2), pp.203-224. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20627447 [Accessed 4 Apr. 2018].

Daniels, G. (1971). The First Civilisations: The archaeology of their origins. Hammondsworth: Penguin.

E. B. (1930). The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, 56(327), 326-326. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.uwtsd.ac.uk/stable/864358

Frankfort, H. (1948). Kingship and the gods. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

George, A. (1985). Observations on a Passage of “Inanna’s Descent”. Journal of Cuneiform Studies, 37(1), 109-113. doi:10.2307/1359964

Griffith, R. (2005). Gods’ Blue Hair in Homer and in Eighteenth-Dynasty Egypt. The Classical Quarterly, [online] 55(02), pp.329-334. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4493341 [Accessed 22 Feb. 2018].

Heersmink, R. (2017). The narrative self, distributed memory, and evocative objects. Philosophical Studies.

Kopytoff, I. (1988). The cultural biography of things: commoditiztion as process. In: A. Appadurai, ed., The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective. Cambridge University Press, pp.64-91.

Lapis Lazuli. (1867). Scientific American, 17(21), 325-325. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26026574

Lawler, A. (2009). Going the Distance to Uncover The Roots of Trade in the Near East. Science, [online] 324(5928), pp.717-717. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20493868 [Accessed 22 Feb. 2018].

MacKay, E. (1925). Sumerian Connexions with Ancient India. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland,(4), 697-701. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.uwtsd.ac.uk/stable/25220818

Majidzadeh, Y. (1976). The Land of Aratta. Journal of Near Eastern Studies, [online] 35(2), pp.105-113. Available at: https://http:..www.jstor.org/stable/545195 [Accessed 22 Feb. 2018].

Manfred Cassirer. (1958). Two Amulets of Cats. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 44, 117-118. doi:10.2307/3855073

Miner, D., & Edelstein, E. (1944). A Carving in Lapis Lazuli. The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery, 7/8, 82-103. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.uwtsd.ac.uk/stable/20140244

Mortazavi, M. (2005). Economy, Environment and the Beginnings of Civilisation in Southeastern Iran. Near Eastern Archaeology, [online] 63(3), pp.106-111. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25067608 [Accessed 22 Feb. 2018].

Payne, J. (1968). Lapis Lazuli in Early Egypt. Iraq, 30(1), 58-61. doi:10.2307/4199837

Pinches, T., & Newberry, P. (1921). A Cylinder-Seal Inscribed in Hieroglyphic and Cuneiform in the Collection of the Earl of Carnarvon. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 7(3/4), 196-199. doi:10.2307/3853566

Schafer, J. (1928). News from Ancient Ur. The Wisconsin Magazine of History, 12(2), 221-224. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.uwtsd.ac.uk/stable/4630756

Smith, S. (1938). An Egyptian Stele and Other Antiquities. The British Museum Quarterly, 12(4), 138-138. doi:10.2307/4422101

Soldier’s Grave at Ur Yields Statue of Woman. (1934). The Science News-Letter, 25(682), 284-284. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.uwtsd.ac.uk/stable/3910510

Tut-Ankh-Amen’s Golden Coffins, the Work of Ancient Egypt’s Most Skilled Artisians. (1926). Scientific American, 134(5), 305-305. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.uwtsd.ac.uk/stable/24976639

Woolley, C. (1928). Excavations at Ur, 1927-8. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, (3), 635-642. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.uwtsd.ac.uk/stable/25221380

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.