Written by Danielle Alexander, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The night sky inspires awe in most who gaze upon it. Our modern perspectives give us a dim shadow of the spectacular sprinkle of stars that litter the midnight sky, a logical lens limiting the imagination. Sometimes, people will cloud gaze and point out images they see amongst the fluffy white water, but I rarely hear those doing the same to the sky.

The constellation of the big bird was mused upon for millennia, and there are many a tale of its’ origin. From the early Mesopotamians to the Romans, this noticeable constellation flies along the Milky Way, away from the North Pole. This northern hemisphere constellation culminates at the end of July.

Ancient Greek Astronomy

Humans have a natural urge to identify familiar things amongst the twinkling stars of that mysterious abyss above us. These narratives were built from astronomical observations and ancient time tracking.

The studying of the sky began long before the earliest Greek sources that (sparsely) discuss them, Homer and Hesiod. The star group narratives adapted per response to generational pressures through time, and they likely developed during the transition from oral to written transmission, but to what extent is unknown.

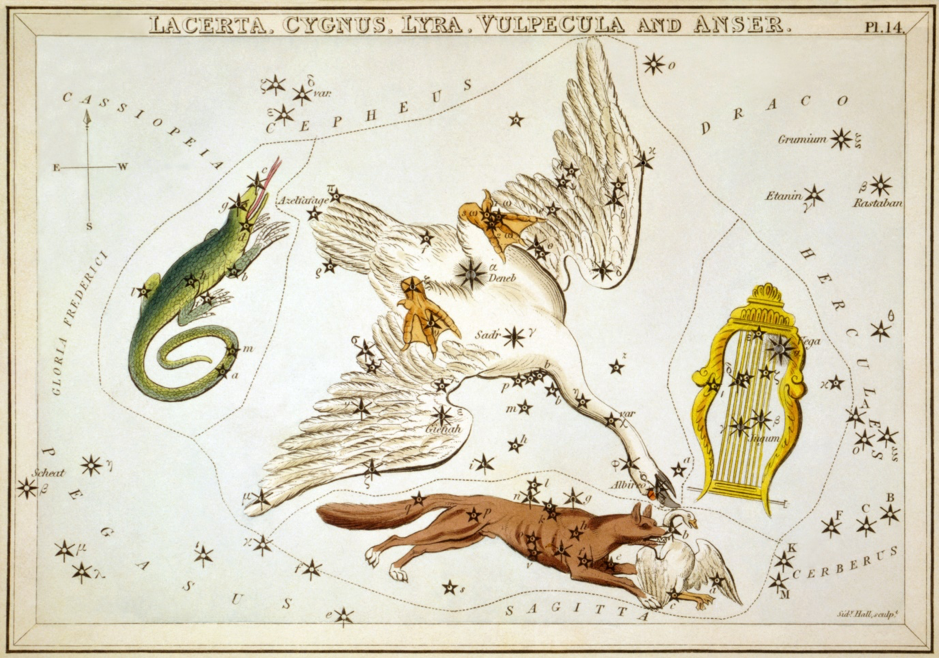

Cygnus Constellation (Artwork from Cornelius 2005:75)

Even though the Greeks were late to the constellation conversation (500 BC), and received a lot of their knowledge from their Eastern neighbours, they introduced the word ‘

katasterismos’ or catasterism; the process of being set in the heavens. Despite knowing many constellations, for navigation and indication of seasonal change,

many extravagant mythic connections were added later.Today, there are 88 constellations officially defined by the International Astronomical Union, and many of them have been accepted since Ptolemy’s The Almagest (A.D 150). Constellations originate in older lands, created by the Mesopotamians between 1300-1000 BC, but the Greek astral mythos canon was solidified by Eratosthenes, in a work now lost to us.

Mythos

This large Bird of thirteen stars is featured within various ancient constellation charts, but it was the Greeks who granted it the name ‘Kyknos’ or Swan. Hygnius notes within The Mythology that many are ignorant to its’ tale and so they misname it ‘Ornis’, referring to birds in general and it was often seen as a goose, before the swan association. However, this not-so-friendly, starry anserine is associated with Apollo and Zeus. For Apollo, the swan is sacred to him because his soul resides within it. How wonderfully poetic! Yet, this is not the story associated with the stars…

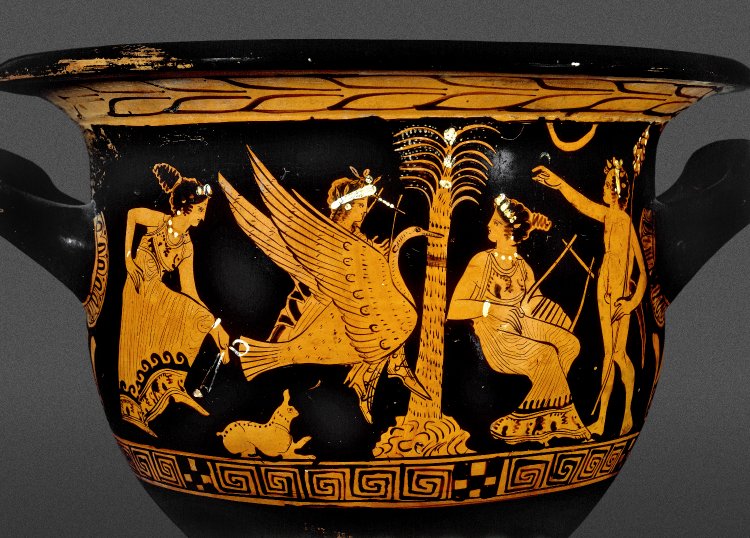

Pottery: red-figured bell-krater (bowl for mixing wine and water) with Apollo riding on a swan, accompanied by two women (perhaps Muses) and a satyr. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Zeus has an eggcellent ploy

Zeus was relentless in pursuing his lust-fueled love for Nemesis. The goddess, desperate to keep her chastity and escape his affections, had transformed into different animals (including fish and beaver) before transforming into a swan and flying to Rhamnous, Attica.

The insatiable king of the gods could not take the hint. He shadowed her transformations and trailed her flight, eventually besting the goddess. Some claim that this unwanted union was received as birds, whereas others claim the goddess had returned to normal form.

Nemesis had allowed a swan to rest upon her lap, taking pity in its plea for protection against an eagle. Not knowing the swan’s true identity, she thinks it safe to rest. Zeus, seizing the opportunity, ‘seduced’ the sleeping goddess and escaped.

In his bid to fly away, he did not change form when ascending to the heavens and was spotted by mortals below, who exclaimed at the new image amongst the stars. Zeus had to adhere to their claims to avoid being caught, especially by his constantly jilted and vengeful wife, Hera. Another source states that he placed the imagery of the flying birds in the sky to commemorate the occasion, but this seems particularly ruthless and foolish on Zeus’ part.

Leda and the Swan, Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

Consequently, Nemesis produced a hyacinth-coloured egg. Swift-footed Hermes swept the egg off to Sparta and

plonked it into the lap of Leda. It is said by Cratinos that it was she who had the face that launched a thousand ships, Helen, who emerged – certainly not an ugly duckling. So, Leda welcomed the matrilineal ruse and claimed it was she who had been unwillingly seduced by Zeus. The older tales state Nemesis undergoes multiple metamorphoses before the consummation occurs in the form of geese, and firmly identifies her as the mother of Helen.

The newer tales describe two eggs for Helen and Dioscuri, the ‘sons of god’, Castor and Pollux (or sometimes Polydeuces). It seems that this twin birth correlates with the Leda myth. Leda’s swan story begins with a bath in the river Eurotas, rudely interrupted by Zeus. Consequently, she lay with her husband, King Tyndareus of Sparta, the same night.

This causes debate on the boys’ divine parentage. Furthermore, academia questions Leda’s relation to Leto, mother of Apollo and Artemis. This creates a round connection for this myth, and Helen’s place within it remains undebated.

Quite often sources state one narrative, or the other, or both, and it is presumed that the confusion could be divided slightly if you consider Leda’s mortality; she could not transform and so must lay with Zeus as a mortal whereas Nemesis had the capability and did so. Eratosthenes, who determined the bird constellations origin lay in the swan sexcapades of Zeus, sourced Cratinos, a 5th century BC Athenian. This poet wrote the lost comedy play, Nemesis, when the impressive sanctuary at the cultic centre of Nemesis, Rhamnous, had been freshly rebuilt.

Nemesis and Arno, Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844): Nemesis Recording Deeds and the God of the River Arno. The Thorvaldsen Museum, Copenhagen.

Nemesis

The goddess Nemesis underwent slight metamorphoses throughout her time as a goddess. Originally, her name meant fortune, neither good nor bad. Eventually, to the Greeks, her name meant ‘dispenser of dues’ and the Romans referred to her as Invidia, or Rivalitas, Jealousy and Jealous Rivalry respectively. By Imperial Rome, she was honoured in the glorified, gory gladiatorial games.

Born as a daughter of Nyx (or sometimes Erebus or Oceanus), she bore her children with the titan Tartarus, of the Great Pit. Nemesis is the personification of the fear of culpable consequence; her actions restore the equilibrium that is dislodged by Tyche (Fortune) or enforce justice, judged by her verdicts and quite often against those guilty of hubris.

First epigraphic evidence of Nemesis emerges from Lemnos in 499BC as an inscription on a bronze helmet. This Rhamnousian act of piety was likely connected to the Nemeseia, the athletic games dedicated to the goddess at Lemnos – not to be confused with a different Nemeseia, a festival for the dead told to us by Demosthenes.

Justice (Dike, on the left) and Divine Vengeance (Nemesis, right) are pursuing the criminal murderer. By Pierre-Paul Prud’hon, 1808

Worship of her was widespread, and in Adrastus, Patrae and Cyzicus she was honoured as a divine virgin aside her traits of retribution. She was often depicted with an apple and a wheel, or scales and whip/axe/sword and a gryphon-pulled chariot. This imagery is visible from a statue at Rhamnous in Attica, the most famous of her cultic centres, of which was said to resemble Aphrodite in likeness, albeit more serious. This statue rested its left hand on the branch of an apple tree, clasped a patera in its’ right hand and, placed on the head, was a stag-adorned crown.

Her sanctuary at Rhamnous, on the north eastern coast of Attica, was built between 460-420 BC. It seems likely that the architect who designed it also created the Hephaesteum and temple of Ares in Athens and another temple of similar design at Sunium. Due to its’ mild size, the cost of construction was kept minimal and local materials were sourced in. Unfortunately, it was never finished, and the steps outside remained unsmoothed.

The sanctuary was located near to the temple of Themis, providing a union with the pair. This is understandable, when considering Greek culture, for both have chthonic associations and represent divine justice – albeit contrastingly.

The Romans reconstructed the temple and appointed it to Livia, the third wife of Augustus and mother to Tiberius, after her deification as Diva Drusilla. It’s believed that Rhamnous was the locale of her association due to the sanctuary’s prior connection to vengeance against eastern enemies. Unfortunately, the temple was destroyed once more in antiquity. The remains are in good condition today.

Temple of Nemesis at Rhamnous, today. Photo by Warwick University.

Chasing those swan tales

It is claimed by Robert Graves in The Greek Myths that this myth reflects the conflicts of ancient Cretan and Hellenic ideologies and politics, and mirrors other trickeries pulled by Zeus in other myths. Yet this myth has been carried on the whispered winds from the ancient lands of Mesopotamia.

They called the star cluster Urakhga and its mythos comes down to us in the Arabic, Rukh, represented by Roc in the legend of Sinbad. This is the story of Sinbad discovering a ginormous egg, clinging onto it when its mother carries it to the Valley of Diamonds to return home with untold riches.

Also, within the region, and told by Hyginus, the swan egg dropped like a tear from the moon into the flowing Euphrates where it was guided to safety by fish and nursed to hatching by doves. From this egg, the goddess of Love emerged. This is eerily like the story of Aphrodite, wouldn’t you say?

Within Serbian belief, swans are the manifestations of water spirits (vilas) whereas, in Hindu myth, the sacred swan birthed the cosmic egg and is sacred to Brahma. Similarly, the Egyptians had a tale of the great, life-giving celestial honker!

An ancient fresco depicting the mythical rape of Leda by Zeus in swan form was unearthed in a bedroom of a house under excavation in Pompeii, Italy.Credit…Cesare Abbate/Pompeii Archaeological Park, via Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

It makes one wonder how such changes in the narrative arises from cultures who were communicating – what was it about the socio-political environment that caused the story to be told that way? In our Grecian version, Nemesis distributes her retribution to Zeus through the chaos of the Trojan War, started by the kidnapping of their offspring, Helen. Here, the honking of a bonking swan does not represent cosmic life energy, but rather the reaping of wrath that leads to legendary destruction.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.