Written by Katherine Smyth, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

One Empire, Two Emperors

Life changed drastically for Marcus Aurelius, and Rome in 161 when Antoninus Pius died, leaving Marcus effectively as the new Emperor. However, although he was granted the name Augustus and the title imperator, and was elected Pontifex Maximus, Marcus appears to have taken these positions with some hesitation, having to be compelled to do so.

He may have been hesitant due to a literal fear of imperial power—horror imperii—or simply because he preferred the philosophic life. But, due to his training as a Stoic, he did not shrug off what he perceived as his duty and accepted the appointment.

It’s important to reflect on Marcus’ relationship with Hadrian, who was of course Antoninus’ predecessor. Although Marcus doesn’t appear to have had any great sentiment for Hadrian, as he did not mention Hadrian in his Meditations, Marcus was no doubt aware of the former emperor’s plans of succession, and ultimately chose to uphold them.

However, this is where Marcus displayed his sense of fairness, justice, and stoicism; he refused to take up office unless Lucius Verus was also granted equal powers. The Senate capitulated, and two Emperors were now ruling Rome equally, working united, a first for the Empire.

Or, at least that is how it appeared. Marcus held more authority—auctoritas—as he had been consul more times than Lucius, and had been involved in Antoninus’ rule and was Pontifex Maximus. To the public eye, it was clear that Marcus was the senior partner in this joint rulership.

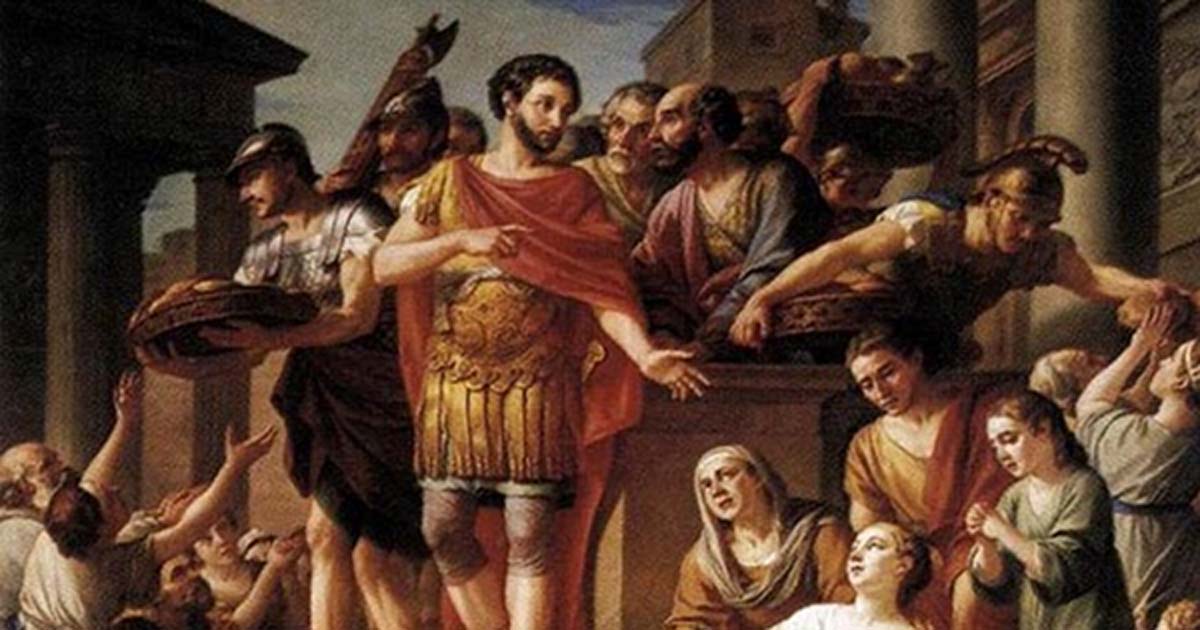

In an unexpected move, the joint rulers then made their way to Castra Praetoria, the Praetorian Guard’s encampment, and Lucius addressed the troops, and made a declaration of a special ‘donative’—a donation which was more than double that from previous emperors, almost several years pay.

With this address and monetary promise, the army immediately declared them as imperatores, and vowed to protect them. This course of action, winning over the military, wasn’t entirely necessary as with previous ascensions, however it was an effective way of solidifying support from the army to the Emperors against any future attacks.

Family Matters

To honor Antoninus, the Emperors held elaborate ceremonies, with his body being cremated at the Campus Martius, and both Marcus and Lucius nominating him for deification. The remains of Antoninus Pius were interred with the remains of Marcus’ beloved children, and former emperor Hadrian’s remains in Hadrian’s mausoleum.

Meanwhile, Faustina was pregnant, and she had dreamt that she would give birth to two serpents, with one stronger than the other. On 31 August (Caligula’s birthday), Faustina gave birth to Titus Aurelius Fulvus Antoninus, and Lucius Aurelius Commodus. The birth was celebrated widely, with coins being minted.

Some time after both emperors’ ascended, Annia Lucilla was betrothed to Lucius despite him formally being her uncle – as he was also adopted by Antoninus, but wasn’t biologically related to her. During the ceremonies, the Emperors made new provisions to support poor children, something akin to previous imperial foundations.

A New Roman Empire

This joint leadership was popular with the Romans, in part because both Emperors’ were direct and lacked the pomp of former rulers. They also earned favor by permitting free speech, something that had been lacking, with those who spoke out being subject to retribution.

Marcus then proceeded to breath new life into the empire, by replacing major officials. The first to change was the ab epistulis, or those in charge of the imperial correspondence. Next, one of Marcus’ former tutors, Lucius Volusius Maecianus was appointed prefect of the treasury, due to his experience as prefectural governor of Egypt. Finally, Gaius Aufidius Victorinus, Fronto’s son-in-law, was made governor of Germania Superior.

At Marcus’ accession to Emperor, Fronto returned from Cirta, and took up residence in his Roman townhouse. Although Fronto did not dare to write to the emperors directly, he did reflect on how the boy he had known had grown into a great leader, and remarked, ‘There was then an outstanding natural ability in you; there is now perfected excellence. There was then a crop of growing corn; there is now a ripe, gathered harvest. What I was hoping for then, I have now. The hope has become a reality.’

In these early days of his reign, a time when all things appeared to move smoothly and without any conflict, Marcus was able to embrace his philosophic nature. Coinage from the era is stamped with the euphemistic words ‘felicitas temporum‘ or ‘happy times’.

Changing Tides

Sadly, these easy days were to end all too soon. Late in 161 or early 162, the Tiber broke its banks and flooded much of Rome. This flooding took the lives of citizens and livestock alike, causing famine and disease to ravage the city. Marcus and Lucius turned their personal attention to the dire situation, and provided for the communities from the Roman granaries to ease their suffering.

Fonto was obviously pleased with his student’s actions, as he continued to write to Marcus throughout the early days of his reign. He also noticed that, with this new prominence of position, that Marcus might have been ‘beginning to feel the wish to be eloquent once more, in spite of having for a time lost interest in eloquence’, something Fronto was all too keen to assist with, but also reminded him of the differences between Marcus’ personal life and his public one.

As a teacher, Fronto could be no prouder of his pupil; Marcus was beloved by his subjects, he was proving to be a wise and capable emperor, and most of all, Marcus was as eloquent as his teacher could wish for. With Fronto’s words ‘Not more suddenly or violently was the city stirred by the earthquake than the minds of your hearers by your speech’, he commended his student’s rhetorical abilities when the Emperor addressed the Senate after an earthquake in Cyzicus. It was clear to all who heard his words: Marcus Aurelius was indeed the Emperor.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.